Introduction

The paradox between capitalism and bank regulation is perhaps one of the most debated topics in financial circles. A capitalist nation such as the United States has adopted a regulatory framework that controls institutions in the financial sector and limits their participation in a free-market economy guided by supply and demand. This paper aims to answer whether or not the regulation of banks is necessary and an infringement of their right to participate in a free market.

The problem this paper investigates is the centrality of banks and the relevance of bailouts in a financial sector regulatory framework. A reconceptualization of the complexity of capitalism is presented in order to demonstrate that the conditions under which banks operate are characterized by complex and immense forces that, if left ungoverned, could be catastrophic. An examination of the history of regulation and its merits is presented in the context of bank bailouts, which have saved banking institutions from the disasters they create. Banks must be regulated in view of their immense impact on the nation’s economic and financial well-being.

The Free Market Economic System

Free markets operate in varied ways around the world, depending on the political systems with which they interact. The presence of incentives designed to maximize profitability determines the eventual political and market outcomes. It is worth considering the fact that in some locales, “free-market capitalism” has resulted in the decimation of democratic institutions (Admati, 2021, p. 678). As a result, the populace has lost trust in its institutions as the interaction of capitalism and democracy defines crises.

In a free market, no government banking system would exist. The government does not control or monitor the financial system. It avoids setting reserve necessities, controlling interest rates, or managing the economy through implementing a monetary policy. In addition, the government in no way alters foreign exchange rates, nor would it hire and investigate banks or hold gold or money made from commodities for banks(Admati, 2021). A free-market system is characterized by a government that desists from offering a clearinghouse for banks. There are no automatic debit and credit services for banks and consumers.

The objective is to achieve total separation of the state from the economy for the same reason and purpose as we need a complete separation of religion and state: force and thinking are opposed. This indicates that people need freedom in order to employ their most fundamental thoughts and emotions (Admati, 2021). Private banks issue subsidiary currency for modest purchases and making changes. The government is not allowed to manufacture coins or confirm their weight and purity.

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism, which is the basis upon which free markets are based, is a seriously debated idea. It is defined as a special kind of liberalism that is deeply associated with laissez-faire economic policies (Graafland & Verbruggen, 2022). Neoliberalism proposes that society’s well-being is best protected by prioritizing the liberalization of organizational and entrepreneurial freedom within an organizational framework that establishes free markets, property rights, and free trade (Graafland & Verbruggen, 2022). The formation of a free-market economy based on voluntary exchange presumes that an effective legal framework that ensures there is no coercion and that contracts are honored exists. The government’s legal structures provide the aforementioned framework.

The free market system assumes that the government does not interfere in the economic sphere through policy proposals. It is expected that the government should limit its activity to guaranteeing the integrity and quality of money rather than adopt a monetary policy designed to stabilize the economy (Graafland & Verbruggen, 2022). Active regulation is viewed as a counterproductive activity, as the government has limited information and no incentive to leverage available opportunities.

Proponents of free market economic systems argue that there is no place for social safety nets. They assume that economic players have the knowledge to make rational decisions at the right time (Graafland & Verbruggen, 2022). The adoption of a system with minimal government intervention would allow markets to flow undisturbed in a manner that would result in the generation of the desired welfare-promoting outcomes while protecting individual rights and freedoms.

Capitalism

Arguments regarding capitalism are often complicated by varied views on the elements involved in making market systems function in a societal context. Markets and corporations are seldom successful in the absence of legal frameworks (Admati, 2021). All institutions are subject to the distortions that arise as a result of imbalances in expertise, power, and information (Admati, 2021). The implementation of effective systems of accountability and governance is essential to ensure that political and economic systems deliver the desired outcomes. The main challenge facing capitalism and other conceptions of a free market is the lack of effective governance structures, which results in confusion.

The contextualization of concepts is essential for the explication of the role, place, and function of the banking sector in a free market. According to the Oxford Dictionary, capitalism is “an economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit rather than by the state” (Admati, 2021, p. 679). It is worth pointing out that the assumption that the state and private entities are distinct and separate presents a misleading dichotomy. Private ownership in civilized societies such as the United States is inextricably linked to the robustness of government policies and legal frameworks that are designed to provide and protect property rights. In addition, government entities play an integral role in promoting business transactions and facilitating contracts.

There is a need to review the contemporary understanding of capitalism. The definition of capitalism as an economic system that is solely governed by the interaction of free market competition forces ignores the fact that competition, markets, and dispute resolution mechanisms require government-controlled legal systems to operate (Admati, 2021). The neoliberal view supports the idea that free markets should operate with minimal government intervention. (Admati, 2021). The neoliberal perspective ignored the interconnected nature of democracy and capitalism. It is evident that legal systems and frameworks are central to the functioning of capitalism. It is vital to understand political mechanisms and policies to address the apparent paradox that exists between banks and free market systems.

The fact that economies thrive on well-intentioned and efficient rules is a foregone conclusion. It is true that poorly enforced regulations have the potential to greatly harm an economy. Opacity and indecipherable processes and procedures may obscure inefficiencies and benefit those capable of making sense of the confusion (Admati, 2021). For instance, complex tax codes riddled with loopholes tend to profit those who know how to navigate the confusion. The suggestion that there should be fewer laws on the basis that some laws fail is incorrect. Such a proposal is not a solution and would lead to an even worse state of affairs. In the event governments fail to develop and enforce rules, markets are likely to band around power structures. This would create a scenario in which powerful entities would set rules and create enforcement procedures that work in their favor.

State Capitalism

The phenomenon of state capitalism has emerged as a rather intriguing and challenging concept in contemporary economies. It is defined as either an authoritarian state-led approach to capitalism as exemplified by China or as a democratic process that employs free-market policies as is the case in the United States (Sokol, 2022). Extraordinary state interventions have become the norm in numerous developed economies such as the United Kingdom and the United States. The conceptualization of the role and position of banks in the economy must be preceded by an explication of the role of finance in modern economies and the role of the state.

Sokol (2022) presents a model of financial flows that conceptualizes the economy as a “network of interlocking ‘financial chains’ defined as both ‘channels of value transfer’ and as social relations that shape socio-economic processes” (p. 5). In essence, value is transferred within the system, and its players are invariably connected to one another, meaning each action affects the entire system. Financial chains are not solely defined by money but rather by the power each of the players wields within the system.

The state’s role in the economy spans beyond debt and credit. Financial investment is increasingly common among developed and developing states around the globe. Sovereign Wealth Funds are used as effective state investment vehicles in financial markets. For instance, sovereign wealth funds in 2020 were estimated at 8.6 trillion U.S. dollars, indicating the significant influence they have on the global economy (Sokol, 2022). State Central Banks have an immense influence on the financial sector. These institutions wield extraordinary power in developed economies. The actions of central banks have immense consequences on banking institutions and the financial system.

Free Market Banking Operations

Effective free-market operations occur in scenarios where society trusts the market players. Trust is vital because free market settings are characterized by limited information, which creates significant information asymmetries and moral hazards (Graafland & de Gelder, 2023). In an economic setup with low transparency, self-interested groups are incentivized to hide limitations and exaggerate positive attributes. Market parties are then forced to contend with the possibility of an extraordinary degree of risk. As a result, the market becomes highly inefficient as a result of heightened transaction costs (Graafland & de Gelder, 2023). The aforementioned risks and costs can be prevented in instances where trust prevails. Trustworthy organizations may be accorded the opportunity to carry out valuable transactions for their clientele.

The public interest theory makes significant contributions to the functioning of free market economies. It posits that government control of economic activity is the direct result of society’s concerns regarding trust, market failures, and fairness (Graafland & de Gelder, 2023). In the event consumers view a firm as untrustworthy, they anticipate high costs and risks, seeing as the organizations in question employ unfair strategies that abuse information asymmetry, meaning support for government regulation will be higher.

In the event companies are not trustworthy, as is the case with banks, government regulation is essential to prevent a financial crisis. The state’s intervention often reduces the freedom of banks, thus reducing the overall risk to society. Graafland and de Gelder (2023) quote the World Values Survey, which proves that distrust increases a society’s support for government intervention, even in instances where citizens are aware of its corruption and ineffectiveness. This demonstrates the fact that individuals prefer government regulations over uncontrolled activity by unruly financial institutions.

It has been demonstrated in the previous sections that economic freedom diminishes immediately after a financial crisis. The immense drop in trust following a financial crisis often results in increased pressure to streamline and improve the efficiency of government regulation (Graafland & de Gelder, 2023). The obscene profits associated with free market operations in the financial sector often prompt banks to engage in risky behavior.

The risks taken are often at the expense of consumer interests, given that good banking standards are often violated in the process. It is worth noting that in the event that the ability of banks to implement extensive compensation schemes is not addressed, the issues that led to a crisis are likely to recur. The regulation of banks reduces consumer vulnerability and protects society’s interests.

The American Banking System

The American financial sector faces significant macro-financial risks. The main risks are tighter financial circumstances, structurally sluggish development in key advanced economies, and a dramatic slowdown in global growth (International Monetary Fund, 2020). It is worth noting that in the near term, a larger-than-expected effect from the COVID-19 virus outbreaks is among the biggest external concerns. Domestically, there is a possibility of a sharper-than-expected and longer-lasting downturn, as well as a major decline in corporate profitability, especially if financial conditions worsen again for a protracted time (International Monetary Fund, 2020).

A downturn in market sentiment, caused, for example, by a worsening public health crisis, policy shocks, trade, or geopolitical tensions, might precipitate risk-off events. Although they are often considered distinct, they might collide in the present setting, perhaps laying the groundwork for a perfect catastrophe. The growing reliance on outsourcing, shared services, and cloud computing across linked platforms raises the possibility that a cybersecurity catastrophe may seriously affect the supply of financial services.

Overall, the supervisory and regulatory structure is strong, although there are still shortcomings in comparison to international norms that must be corrected. In 2015, the United States framework was determined to be in excellent conformance with international norms. Nonetheless, a number of recommendations remain pending (International Monetary Fund, 2020). In addition to complete compliance with global requirements, the International Monetary Fund believes that given the system’s architecture and the emergence of new risks, extra strengthening in some areas may be necessary.

The Role of Banks

Firms and households in developed nations are increasingly dependent on banking services. For instance, savers have accumulated a significant amount of wealth that is linked to financial markets in the form of bonds, stocks, and deposits (Chwieroth & Walter, 2020). The shift of household wealth portfolios towards increasingly volatile market-traded assets such as defined contribution pensions has increased individual concern over the value of their wealth. Overall dependence on the financial system has increased globally as individuals rely on credit, finance housing, and improve their welfare (Chwieroth & Walter, 2020). This means that households have plenty to lose in the event of a financial crisis.

Banks have significantly increased access to credit, which has increased household financial fragility immensely. This is compounded by the fact that the risk of wealth losses in the event asset prices fall is especially high (Chwieroth & Walter, 2020). Low and middle-income households in developed economies depend on credit as a means of acquiring assets, while developing countries rely on it as a way of accessing essential services such as healthcare and education. In essence, households have a significant degree of interest in bailouts because they maintain the flow of credit during crises.

It is worth considering that the increasing interconnectedness and scale of financial firms have reduced the ability of private firms to support insolvent banks immensely. Therefore, the state has been forced to utilize its unique borrowing and taxation abilities to serve as a residual guarantor when financial markets are in turmoil (Chwieroth & Walter, 2020). There is evidence that government policies meant to stabilize the financial sector have worked in the past. According to Chwieroth and Walter (2020), there were virtually no crises in the thirty years following the 1945 policies designed to guarantee financial stability. The world’s financial systems were largely undisturbed, seeing as governments were actively involved in the regulation of financial system processes.

How Banks Remain Profitable in the Context of Regulation

Interstate Banking and Mergers

The banking sector favors mergers and acquisitions because they increase the potential for generating immense profit. Newman (2020) notes that after the 2008 financial debacle, numerous banks merged in order to avoid failing. For instance, Bank of America acquired Merrill Lynch, and JP Morgan Chase acquired Bear Sterns (Newman, 2020). However, as the crisis deepened, merging came to a halt, seeing as big banks were allotted blame for the financial crisis by consumers as well as the government. The public’s frustration was evident in the Occupy Wall Street movement, and the government instituted stiff regulations to regulate banking activities in the United States. Banks have recently re-initiated measures aimed at facilitating mergers and acquisitions in recent years. The organizations recognize that having a large market share is immensely profitable for banking institutions.

Interstate banking is a common phenomenon in the United States. The Riegle-Neal Act played a critical role in allowing interstate banking, which is more often than not a by-product of bank mergers. It is worth considering the fact that allowing bank mergers significantly increases the risk of economic moral hazard. This is a scenario in which banks overestimate their value and engage in risky behavior because the people making the decisions are not impacted by the consequences of their actions (Newman, 2020). Large banks are an economic risk because their collapse is likely to impact a significant section of the economy.

Investment and Commercial Services

There is significant concern regarding the consolidation of banking activities following the repealing of legislation aimed at preventing engagement in investment and commercial services under a single roof. Such activities are often discouraged because they allow banks to leverage a significant degree of market power to implement risky strategies. While retail and commercial banking is relatively safe, investment banking is inherently risky.

Banks often use stable funds from their commercial section to engage in risky investments in a bid to increase their net interest margin. In addition, the financial sector’s market size decreases significantly when banks can run commercial and investment divisions simultaneously. A decline in the number of people running banks serves to concentrate power in the financial sector, leaving major decisions under the control of a few influential individuals.

The Regulation of Banks: Is it a Paradox?

The high frequency of crises in recent years underscores the need for regulation. However, it seems paradoxical that banks should be heavily regulated, yet they are expected to compete and generate profit in a free market. This paper argues that bank regulation is not paradoxical, given the institutions’ important role in society. Admati (2021) notes that the 2007-2009 financial crisis was the result of poor regulation and ineffective enforcement, which encouraged an unprecedented buildup of risk.

Corporate investors obscured risks, and government agencies failed in their roles as regulators. Extraordinary support from Central banks and governments was necessary to keep the system functioning. The aforementioned efforts notwithstanding, the global economy descended into a recession. Some effects of the crisis are still felt today as banks continue to wreak havoc in environments characterized by complex regulatory metrics that are incapable of detecting weaknesses that risk crippling the global economy.

The global financial sector has become increasingly opaque in recent years. Offshore financing systems that undermine tax collection and facilitate the laundering of illicitly acquired money have grown exponentially. Ineffective laws fail to curb ills such as money laundering, as demonstrated by the 200-million-pound money laundering operation in Danske Bank’s Estonia branch (Admati, 2021). Banks do not wish to operate in a free-market system given the fact that their symbiotic and often corrupt interactions with the government serve to benefit the interests of select powerful individuals.

The Conservative View

The classic, economically conservative view of banking policy applies the laissez-faire economic model to issues of regulatory control. The paradigm proposes that the economy’s “invisible hand” will adjust and alter conditions in response to specific occurrences (Newman, 2020). Many conservative theorists are of the view that the economy should be left alone as much as possible. In terms of banking policy, the conservative approach proposes allowing banks to self-regulate with minimum government intervention (Newman, 2020).

In essence, banks would be free to form mergers with others, lend to anyone they desire, and form investment and commercial conglomerates. Most conservatives are of the view that American banks should do whatever they need to compete in an increasingly global economy. Their actions must, however, be within reasonable bounds, as enshrined in banking policy. Conservatives often claim that nations such as Germany have successfully created large banking conglomerates due to limited government interference (Newman, 2020). Conservatives frequently oppose additional regulation, claiming that bankers have a deeper knowledge of the industry working compared to government authorities.

The U.S. Federal Reserve

The U.S. Federal Reserve has played a central role in shaping America’s financial environment as well as the functioning of the banking sector. The Fed shot into focus in the 1930s when the United States was reeling after the impact of an overwhelming financial crisis (Sokol, 2022). It is worth noting that the Fed did not act as the lender of last resort, leading to perhaps one of America’s most devastating crises.

The deflation and economic depression that followed resulted in the loss of employment and the devastation of livelihoods. The Great Depression shaped America’s Central Bank into what it is today. America’s central bank is not as independent as other similar institutions in other developed nations. The Federal Reserve Bank’s policies are often reviewed by the U.S. Congress (Sokol, 2022). However, the institution’s decisions do not need to be approved by any institution or individual in government.

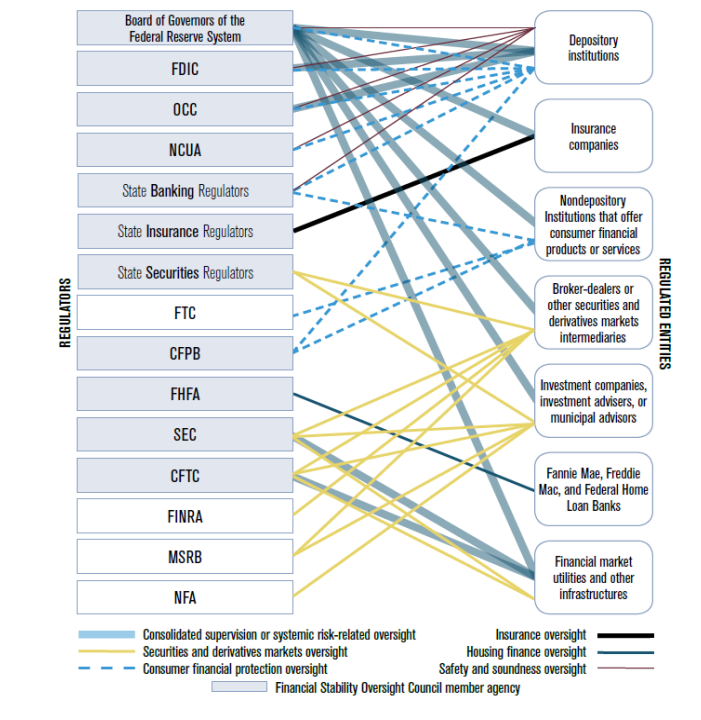

The regulatory and supervisory architecture in the United States is complex, placing a premium on cross-agency communication and collaboration. In banking, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) serves as an efficient coordinating tool, with banking institutions issuing joint Notices of Proposed Rulemaking, boosting uniformity in strategy and messaging (International Monetary Fund, 2020). There is no official coordination structure between the CFTC and the SEC in the securities and derivatives markets, while Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) are in place for data exchange and there is regular unofficial cooperation.

The continuously shifting financial landscape poses additional obstacles. Digital and fiscal creativity are decreasing entry barriers and allowing enterprises outside the Federal Reserve’s regulatory boundary to offer financial services (International Monetary Fund, 2020). Innovations in finance have resulted in the migration of mortgage activity away from banks. In addition, virtual assets (VAs) and virtual asset service providers (VASPs) offer services that are comparable to those provided by conventional securities agents or other financial institutions without being held to the same standards and obligations.

The Federal Reserve’s role in recent times has been amplified by a variety of crises. For instance, the 2008 financial crisis necessitated interventions such as quantitative easing to help protect the economy (Sokol, 2022). In addition, similar measures had to be implemented in the aftermath of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which brought the global economy to a standstill (Sokol, 2022). Crises significantly amplify the monetary organization’s power in matters of economy. The Fed essentially acts as the state’s banker as well as the financial market’s custodian.

The Federal Reserve Act’s architects purposefully opposed the notion of a sole central bank. Instead, they envisioned a central banking system with three distinguishing characteristics: These are a central controlling Board, a decentralized functioning structure with twelve Reserve Banks, and a mix of public and private features (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021).

Although several aspects of the Federal Reserve System resemble private-sector companies, the Federal Reserve was formed to serve the general population’s interest. The Federal Reserve System is comprised of three major entities. These are the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the Federal Reserve Banks, and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). The Board of Governors is a federal government entity that is held accountable by the United States Congress.

When the Federal Reserve System was established, the U.S. was split geographically into twelve Districts, each with its own Reserve Bank. District borders were established on the basis of existing trade regions in 1913 and associated economic reasons, which means they do not always align with established state lines (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). Each of the twelve Reserve Banks was initially designed to function independently of the others.

Discount rates—the interest rate charged to commercial banks for borrowing money from the Reserve Bank—were expected to fluctuate (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). The establishment of an independently calculated discount rate suitable for each District was seen as the most significant monetary policy instrument at the time. The notion of national economic policymaking was not sufficiently defined, and the consequences were significant.

Commercial banks that belong to the Federal Reserve System own shares in their District’s Reserve Bank and are eligible to elect a maximum of six of the Reserve Bank’s directors (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). It is worth noting that the Board of Governors appoints the remaining three candidates. Most Reserve Banks have a minimum of one Branch with its own board of directors.

The Reserve Bank or the Board of Governors nominates branch directors. Directors act as liaisons between the Fed and the private sector (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). As a group, directors contribute a diverse range of private-sector expertise to their tasks, providing them with crucial insight into the economic situations of their various Federal Reserve Districts (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). The Reserve Bank’s head office and branch directors add to the overall understanding of the System. The highly complex regulatory framework is highlighted in Figure 1 below.

Note: Adapted from International Monetary Fund (2020).

Monetary Policy

Monetary policies have a significant impact on the behavior of institutions in the banking sector. It is vital to explain why Central Banks are critical to the functioning of the financial sector. The monetary policy is designed to ensure that the rate of inflation is maintained between 2 and 2.5%, keep unemployment low, and maintain reasonable long-term interest rates (Kausa & Sahi, 2021). The Federal Reserve is tasked with maintaining the nation’s economic growth at between 2 and 3% in order to increase the overall gross domestic product (Kausa & Sahi, 2021). America’s monetary policies incentivize banks to provide credit and businesses to borrow from financial institutions. The Federal Reserve’s regulations have a direct impact on the growth of the banking sector. The organization regulates market interest rates, which have a direct bearing on the profitability of banks.

The Federal Reserve plays a critical role in the context of financial crises. The worldwide financial disaster, which began in the summer of 2007, got extremely bad in 2008 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). At the outset, the Federal Reserve reacted by extending its lending to banks facing liquidity challenges via its normal discount window. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve launched various emergency lending initiatives to meet financial institutions’ short-term liquidity requirements, as well as to assist in reducing tensions in several markets (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021).

Accountability and openness are promoted by regular congressional testimony and reporting. The Monetary Policy Report is sent to Congress semiannually by the Board (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021). This report discusses the conduct of monetary policy as well as economic events and future predictions. The Chair speaks before the Senate Banking Committee when this report is issued.

Banking Regulation History

The regulation of the financial sector is not a new concept. It was necessitated by adverse economic aftershocks that were created by an uncontrolled banking sector, as is the case today. In response to the aftermath of the Great Depression, the United States passed the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, which effectively separated commercial banks from investment banks (Newman, 2020). The law stipulated that banking institutions had a year to decide whether they were investment banks, which could not own commercial outfits, or commercial banks, which were prohibited from dealing with securities (Newman, 2020).

Compliance with the regulation meant that numerous institutions had to split, as was the case with JP Morgan, which was forced to create Morgan Stanley to deal with investments. The law also resulted in the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which was tasked with ensuring up to 250,000 dollars for depositors in member banks, which served as protection in the event an institution failed (Newman, 2020). The rules were designed to protect the public from the catastrophic aftermaths of collapsed banks.

The banking sector remained fairly stable until deregulatory measures were implemented. In the mid-1990s, numerous laws intended to repeal key sections of the Glass-Steagall Act were passed (Newman, 2020). For instance, the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking Act, which was passed in 1994, repealed regulatory measures that stopped banks from spreading across state lines (Newman, 2020).

The result was the establishment of national banks, which grew immensely in size and power. In addition, further legislation allowing banks to conduct investment, commercial, and retail services under one roof was passed. The rampant deregulation facilitated bank mergers and acquisitions, and by 2008, there were only 8000 banks in the country, down from approximately 15,000 (Newman, 2020). Large financial institutions with a massive impact on the nation’s economy became the norm.

The newly formed mammoth organizations assumed excessive risk, resulting in an economic downturn that affected American livelihoods. After the laws that mandated the separation of banking services were repealed, banks decided to bundle commercial and retail businesses with risky investment strategies. The use of their clients’ resources in uncertain markets such as the housing sector, which promptly collapsed, resulting in massive losses in the banking sector, which affected all of their clients (Newman, 2020). This was because the investment arms were directly linked to the retail and commercial segments.

One of the key issues that negatively impacted the banking sector’s performance was the repeated approval of inappropriate loan rates. Banks approved numerous subprime mortgages which were then used to back other investments (Newman, 2020). It is argued that the lack of government oversight precipitated one of the worst financial crises the United States has experienced in recent years.

In a similar fashion to the Great Depression, legislation was passed to protect the economy from another financial crash. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act is perhaps the most important piece of legislation that was passed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis (Newman, 2020). The Act resulted in the creation of the Consumer Protection Bureau which was tasked with overseeing the activities of big businesses such as banks and credit card companies. The law also placed limits on speculative activities in financial institutions.

Recent administrations have implemented measures aimed at repealing numerous laws that were implemented to ensure banks are regulated. For instance, the Trump administration passed the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, which raised the size threshold for banks from 100 billion dollars to 250 billion dollars in assets in 2018 (Newman, 2020). The argument in support of the bill was that increasing the threshold would facilitate the provision of services to regions of the U.S. that had limited banking activity.

Financial institutions around the world are under tremendous strain to improve their performance and risk management. The financial services sector still remembers the 2008 World Banking Crisis as the worst economic crisis since the 1929 Great Depression (Rastogi et al., 2022). Prior to 2008, the oversight apparatus received widespread criticism for failing to manage bank risks (Rastogi et al., 2022). It is critical to explore bank regulation and its impact on the institutions’ performance.

Banks have frequently been seen as drivers of economic advancement and the pivot of the growth of the financial system. The amount of non-performing assets (NPAs) on a bank’s balance sheet is an important indicator of its financial condition. NPAs are loans in which the payment of interest remains unsettled for more than a few quarters (Rastogi et al., 2022). NPAs have a detrimental impact on the institution’s liquidity as well as profitability, hindering loan expansion and causing turmoil in the country’s economy. As a result, healthy banks are necessary for an economy to flourish.

The Necessity of Regulation: Demystifying the Paradox

Banks have become an immensely powerful force in the American economy. It is estimated that ten of the country’s most influential banks control approximately 12 trillion dollars in assets (Newman, 2020). American savers and investors have deposited most of their money in a few powerful banks, making them too large to fail.

The American economy’s reliance on banks has fueled the belief that the financial sector is likely to collapse in the event anything catastrophic happens to these institutions. Newman (2020) notes that banks frequently engage in risky behavior that is likely to jeopardize the economy in the absence of effective regulatory mechanisms. There is a need to ensure that people’s assets and livelihoods are protected from rogue agents in banking institutions.

Breaking Up Banks

The idea that banks should be broken up has gained a significant degree of traction in various circles. The idea of breaking up banks is a policy proposal aimed at mandating the division of the assets of institutions deemed too big to fail as a way of preventing catastrophic outcomes in the event of their collapse (Newman, 2020). The idea is both controversial and polarizing, with some schools of thought maintaining that banking institutions should be allowed to experiment and apply innovative strategies with investments. The opposing view is that Congress should implement policies that hold players in the industry accountable for their actions.

Predatory Lending

Banking institutions have been known to participate in predatory lending, which is an immensely detrimental practice that harms households. Subprime mortgages, as previously stated, are granted by individuals who would not qualify for regular mortgages (Newman, 2020). Similarly, predatory lending occurs in instances where financial institutions offer loans or mortgages to individuals who are unlikely to honor the agreed-upon terms due to poor credit histories (Newman, 2020). It can also occur in scenarios where the bank falsifies information regarding what the consumer is required to pay, thus making the purchase appear more inexpensive and realistic than it actually is. The practice of predatory lending is prohibited by law, yet it is still prevalent in modern banking institutions.

Differentiating Regulation from Socialism

Regulation is not a form of socialism because economic setups involve the flow of value in both directions. The interactions between the state and the banks it regulates are far from simple supply and demand transactions. The value that is transferred between economic players is shaped to a large extent by extant power relations. The economy is an intricate network of financial chains that play a critical role in shaping financial geographies, which the state, banks, and numerous other financial players define.

Rather than control money, as is the case in socialism, the state is an active economic participant, given it spends resources through fiscal policies and performs other essential services, including regulation. One of the government’s key functions is borrowing, which has a significant impact on the entire economy.

Debt issued as government bonds is the foundation for the economy’s functioning in view of the fact that it serves as a source of safe collateral to support numerous financial sector transactions on which banks depend (Sokol, 2022). This has made government bonds the foundation of many contemporary financial systems. It is evident that the interdependence between financial markets and the state’s regulatory framework is not socialist in nature. The mechanisms the state has implemented govern banking activities and do not involve direct ownership of resources.

Bank Bailouts

The global financial crisis prompted the proposal of varied views regarding policy responses meant to keep banks in check. There is significant doubt that the measures that have been implemented have the capacity to prevent another financial meltdown. The idea that bailouts are a consequence of pressure from the financial sector is only partly true. The Bagehot model, which was developed from Walter Bagehot’s principles of crisis resolution, advocates for the intervention of central banks in financial systems (Chwieroth & Walter, 2020).

The model proposes that central banks such as the Fed should provide lender-of-last-resort services to solvent banks through the free advancement of good security (Chwieroth & Walter, 2020). The model further stipulates that while the lending should be unlimited, it must be based on punitive rates in return for good collateral as a means of ensuring that the government does not subsidize banks in need.

The concept of lending as a last resort is a diversion from pure market forces, given that it involves the implementation of policies that prevent ordinarily solvent banks from failing. According to Chwieroth and Walter (2020), the phenomenon places the burden of permanent insolvency on banks and their shareholders rather than on taxpayers. This means that in certain circumstances, central banks can oversee the closure of insolvent banks and oversee the recapitalization of non-performing banks by private investors. Bailouts, more often than not, involve the use of taxpayer resources to delay the dissolution of banks that are experiencing insolvency.

Financial crises are characterized by a significant degree of uncertainty. It is estimated that 29 billion dollars were used to bail out collapsing banks during the 2008 financial crisis (Better Markets, 2019). The actions were justified by concerns that allowing the banks to fail would result in the destruction of the entire financial system, which would cause irreparable harm to the American economy.

The reasons provided for the bailouts included the argument that the collapse of America’s giant banks would result in credit contractions where the institutions in question would be incapable of offering credit intermediation (Better Markets, 2019). In addition, the collapse of major banks would result in the crippling of payment systems and deny organizations the financial resources they require to run operations and pay employees. Evidently, there was a need to bail out the giants using taxpayer resources.

The European Context

During the global financial and subsequent European crises, policymakers had two main methods of coping with rising credit concerns. On the one side, national governments enacted bank rescue programs such as deposit guarantees, capital injections, and debt guarantees (Fratzscher & Rieth, 2019). On the other side, the implementation of monetary policy was crucial because it facilitated the supply of enormous amounts of money to banks. It also ensured the government’s participation in sovereign debt markets through outright purchases or by offering an implicit assurance against a speculative run.

There is a growing body of theoretical literature on how government regulations for banks impact their risk as well as sovereign risk. Guarantees and capital injections can help to avert bank runs, decrease ambiguity, and increase financial system robustness (Fratzscher & Rieth, 2019). However, in the event the bailouts are big and pose a threat to the sustainability of public debt, such a risk transfer may ultimately worsen the economy’s overall outlook, causing sovereign and bank risk to move into lockstep (Fratzscher & Rieth, 2019). There is also a substantial body of evidence on the effects of unconventional monetary policy on financial markets during crises.

The empirical data evaluated by Fratzscher and Rieth (2019) suggest that sovereign and bank risk have significant cross-country spillovers. Spillovers result from shocks to sovereign risk in the eurozone periphery to sovereign banking institutions in the core, as well as shocks to banks in the periphery. What is notable is that the impact of credit risk on the core nations has been comparable to, if not greater than, the effect in the other way (Fratzscher & Rieth, 2019). This is significant since the core nations account for a substantially higher part of the eurozone and its underlying sovereign debt market.

Finally, empirical evidence demonstrates that ECB non-standard measures and national government bank bailouts lowered the credit risks of banks and sovereigns in almost all situations. They also had a substantial influence on non-financial enterprises’ stock returns as well as credit risk. Announcements regarding the Securities Market Programme (SMP), which includes government purchases and Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT), which indicate a conditional commitment to buy public debt, reduced sovereign and bank CDS spreads immensely (Fratzscher & Rieth, 2019).

Similarly, fiscal policymakers’ pronouncements of bank bailouts resulted in sovereign and bank spreads have fallen dramatically. Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTROs) (Fratzscher & Rieth, 2019). The findings demonstrate an intriguing yet obvious distinction between the public declaration and the actual execution of LTROs.

Criticism of Bailouts

Taxpayer Losses

Bailouts have historically had various effects on citizens. Throughout the Great Depression, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (“RFC”) made a total profit of 160 million dollars on its five hundred million dollars of capital (Scott, 2020). However, the FDIC paid the sum of 1.1 billion dollars for the Continental Illinois National Bank’s bailout, while taxpayers paid 123.8 billion dollars, or 81% of the overall costs (Scott, 2020). It is vital to note that TARP’s bank bailout initiatives are unlikely to result in a tax loss; in fact, they will be lucrative. However, in view of the risk that the Treasury assumed, it remains to be seen whether the profit was substantial.

Even if bailouts are ultimately not costly to taxpayers, this is not known in advance of the investment. The predicted cost to citizens at the moment that Congress approved TARP was significantly higher (Scott, 2020). However, if the goal is to prevent government losses, any future losses will be borne by lenders or their shareholders, or a portion of them, via ex-post assessments (Scott, 2020).

Section 134 of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which authorized TARP, states that the head of state must submit a bill to Congress that recovers a sum equal to the TARP shortfall from the banking sector in order to ensure that the bailout does not increase the deficit or the national debt (Scott, 2020). It is expected that the president will implement measures designed to collect the spent sum over a specified period.

The Inefficiency of Bailout Programs

Bailout programs are seen as largely inefficient, given the fact that there is limited emphasis on behavior change. Prior to the financial meltdown of 2008, the most effective bailout in a developed economy was undoubtedly the early 1990s Swedish bank bailout (Scott, 2020). Following the fall of the housing market, numerous Swedish banks were left with huge amounts of soured property debts.

The government declared an all-encompassing guarantee of financial obligations and seized control of the main banks (Scott, 2020). Sweden eventually paid the bare minimum after relinquishing its bank holdings a few years later (Scott, 2020). However, bank bailout programs implemented to avert crises are not always effective. It runs the risk of turning a single bailout into a series of operations to support bankrupt banks for an indefinite amount of time with no genuine prospect of revival.

Japan, like many other developed economies, has had its fair share of economic crises. The Japanese “lost decade” is a well-known example of a long-term bailout (Scott, 2020). Since the crash of Japan’s equity and real estate markets in 1990, both major and minor Japanese financial institutions have been plagued with defaulted loans (Scott, 2020).

Throughout the 1990s, the government attempted to rescue banks by purchasing nonperforming loans (NPLs) (Scott, 2020). However, it continued to postpone its measures, acknowledging the full extent of the NPL crisis by supporting dubious accounting procedures because of the enormous social cost of corporate bankruptcies and the political implications of acknowledging big losses. After the Japanese economy started recovering and the government began to handle the NPL problem seriously in 2003, the Japanese financial system began to normalize (Scott, 2020). Banks seemed capable of settling public loans within a few years by 2006. The major banks have already done so, while regional banks are still struggling.

Creating a Moral Hazard

The greatest argument against bailouts provided by governments is the danger of moral hazard. Individual enterprises and the market may have ill intentions if they believe that government intervention will save them (Scott, 2020). Because risk-taking becomes a biased bet as a result of moral hazard, firms tend to adopt more risky strategies than they normally wound under ordinary circumstances. Investors, particularly debt investors, may be less motivated to track the firm’s performance (Scott, 2020). As the firm grows too large to fail, implying that it is presumably deserving of a bailout, it may gain an unfair competitive edge over other enterprises due to lower financing costs.

Bailouts and Lending

Bailout initiatives frequently serve the dual objective of securing the financial sector and mitigating the negative effects of the lending market meltdown on the actual economy. Evidently, there is an intrinsic friction between the two goals. If the financial system fails primarily as a result of business failures in the economy as a whole, as in Japan, providing loans to these failed enterprises would merely create additional undesirable debt (Scott, 2020). However, if the actual economy could keep growing under typical lending circumstances and the economic downturn was caused by an error in the finance sector itself, the results would be different. In such a scenario, a government bailout of the financial system ought to boost commercial lending and expand the overall economy.

Although overall lending terms have evolved dramatically since the financial crisis’s height, many criticized TARP for lacking the ability to stimulate the actual economy. Firstly, critics of TARP frequently highlight a fault in the CPP’s architecture. When the United Kingdom government invested in RBS and Lloyds, there were specific contractual demands that they retain their pre-crisis lending rates (Scott, 2020).

The U.S. Treasury placed no such obligation on CPP members (Scott, 2020). To be fair, the FDIC has directed the banks it controls to keep track of the usage of TARP monies as well as funds acquired through FDIC debt guarantees. Furthermore, an interagency statement encourages all financial institutions to offer loans to financially viable applicants.

Bailouts: Questioning Their Relevance

In the United States, neoliberalism and bailouts coexist, albeit with a significant degree of unease. It is worth considering the fact that neoliberal governance generally allows for a form of government action that restricts market competition, as is the case with tariffs or entry restrictions (Chwieroth & Walter, 2022). However, crisis bailouts, which erase market fear by introducing blanket state assurances and nationalizations, are radical deviations from neoliberalism with significant implications for markets and government (Chwieroth & Walter, 2022). Thus, the increasing prevalence of financial bailouts appears to be antagonistic to the neoliberal objective.

Influential organizations have attempted to limit the power of fiscal and monetary policymakers to conduct bailouts. These include citizens as well as public sector recipients who see bailouts as a form of corporate welfare that jeopardizes their access to public funds. Creditors may also reject bailouts if they cause inflation and jeopardize currency exchange agreements (Chwieroth & Walter, 2022).

Robust financial and non-financial enterprises may oppose bailouts of weaker rivals if their collapse provides low spillover concerns. Unleveraged persons or those less tied to financial markets due to smaller amounts of saving, borrowing, and monetary asset ownership may consider bailouts of leveraged persons and wealthy financial property owners unjust. Furthermore, neoliberal standards give policymakers like central banks and regulators a critical tool to protect their autonomy.

Pressure to restrict public bailouts has coincided with increased demand for the state to contribute budgetary resources to minimize the terrible problems that preceded financial growth. The traditional “solution” was to define parameters for state assistance to private enterprises in financial crises in order to safeguard the financial landscape as a whole. The concept of a lender of last resort was created to protect the financial system from utter collapse.

As contemporary crises worsen, the political incentives for countries to transition to a bailout plan intensify while the variables that previously favored policy prudence flip. In this stage, financial businesses’ shareholder equity has been drained, making fresh stock issuing at a fair cost impossible (Chwieroth& Walter, 2022). Crisis intensification reduces opposition inside governments and policy bodies, primarily by diminishing the power of players who oppose bailouts on principle. Deepening crises undercut the assumption that financial discipline must be preserved by presenting a more serious danger to family wealth and the sustainability of many enterprises (Chwieroth & Walter, 2022).

In comparison to the earlier emphasis on limiting moral hazard, the goal of keeping the financial system, economy, and family sector wealth from collapsing becomes the priority. This necessitates a quick turnaround by administrations pursuing political survival. If passing a new law is challenging, authorities might try to adapt existing institutions and norms. This could additionally have the benefit of seeming less like a policy reversal. Conversion techniques may begin to dominate during this stage.

At this time, crisis bailouts are necessary, and they take many different forms. Various steps can be taken to address the apparent paradox between free market operations and regulation. In addition to providing crisis liquidity to potentially insolvent organizations, authorities and central banks can facilitate corporate reorganizations and enforce deposit freezes to safeguard banks (Chwieroth & Walter, 2022).

Additionally, the government can expand deposit insurance beyond current limits, guarantee the debts of insolvent entities, buy assets from them at high prices, and recapitalize bankrupt organizations by injecting public funds. Greater worldwide threats, abrupt lockdowns, unpredictable situations, the quick shutdown of all operational operations, and the global propagation of new coronavirus produced an unsettling scenario for whole organizations, manufacturing units, supply networks, and the financial sector (Karim et al., 2022). The banking industry, which plays an important role in the economy, is not immune to the difficult circumstances that have arisen due to COVID-19 all over the world. Banks are seen as the primary drivers of economic growth since they directly connect to the supply and demand for money within an economy.

Conclusion

The idea that banks can exist in an environment without regulation is untenable. There is no paradox between bank regulation and operation in a free market. The contemporary economic climate has evolved and includes more forces than the traditional demand and supply. The complexity of financial processes and the increased societal dependence on banks for credit, investment, and asset acquisition necessitates implementing regulatory measures designed to tame rogue agents.

While free market systems seem ideal, they are untenable in the current political and economic climate, where protecting the people’s interests is the priority. Governments are key players in the nation’s financial sector and are, in many ways, integral to its functioning. The view that the state can be separated from the economy ignores the economic realities that countries today must face. Weak and inefficient regulation has resulted in some of the worst financial crises in recent years. The government must actively regulate banks by providing a level playing field for all its participants while protecting the public’s well-being and interests.

References

Admati, A. R. (2021). Capitalism, laws, and the need for trustworthy institutions. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 37(4), 678–689. Web.

Better Markets. (2019). Wall Street’s six biggest bailed-out banks: Their rap sheets & their ongoing crime spree. Web.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2021). The Fed explained: What the central bank does. Web.

Chwieroth, J. M., & Walter, A. (2020). Great expectations, financialization, and bank bailouts in democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 53(8), 1259–1297. Web.

Chwieroth, J. M., & Walter, A. (2022). Neoliberalism and banking crisis bailouts: Distant enemies or warring neighbors? Public Administration, 100(3), 600–615. Web.

Fratzscher, M., & Rieth, M. (2019). Monetary policy, bank bailouts and the sovereign-bank risk nexus in the Euro Area. Review of Finance, 23(4), 745–775. Web.

Graafland, J., & de Gelder, E. (2023). The impact of perceived due care on trustworthiness and free market support in the Dutch banking sector. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(1), 384–400. Web.

Graafland, J., & Verbruggen, H. (2022). Free-market, perfect market and welfare state perspectives on “good” markets: An empirical test. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(2), 1113–1136. Web.

International Monetary Fund. (2020). United States: Financial system stability assessment. Web.

Karim, S., Akhtar, M. U., Tashfeen, R., Raza Rabbani, M., Rahman, A. A. A., & AlAbbas, A. (2022). Sustainable banking regulations pre and during coronavirus outbreak: The moderating role of financial stability. Economic Research, 35(1), 3360–3377. Web.

Kausa, A., & Sahi, C. A. I. (2021). Impact of bank capital and monetary policy on lending behavior of USA banking sector before and after global financial crises. The Journal of Educational Paradigms, 3(1), 171–181. Web.

Newman, L. (2020). The power of the American banking sector. In Harvard Model Congress. Web.

Rastogi, S., Sharma, A., Pinto, G., & Bhimavarapu, V. M. (2022). A literature review of risk, regulation, and profitability of banks using a scientometric study. Future Business Journal, 8(1), 1–17. Web.

Scott, H. S. (2020). Criticisms of bailouts generally. In Connectedness and Contagion (pp. 265–272). MIT Press. Web.

Sokol, M. (2022). Financialisation, central banks and ‘new’ state capitalism: The case of the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 1–20. Web.