Introduction

Over the past century, tourism has been one of the most fast-growing industries and is essential to the visitor economy. Heritage attractions constitute one of the reasons for the increasing popularity of tourism. In general, heritage attractions are points of interest, referring to exhibitions, museums, traditional sites, and other places of historical or cultural value (Carbone et al., 2020). Therefore, cultural heritage management plays an essential role in tourism development and positively affects the visitor economy. At present, the rapid growth of businesses is significantly obstructed by the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent restrictions. Nevertheless, technological advancement allows to mitigate these challenges and offers the customers a large variety of virtual tours, mixed reality approaches, and other methods of increasing the visitors’ engagement in heritage attractions (Bae et al., 2020). Ultimately, the current work examines the role of tourism and heritage attractions to destinations and analyses the impact of contemporary technologies on the industry.

Impact of Tourism and Heritage Attractions on Destinations

As mentioned briefly before, the popularity of tourism has increased greatly over the last century, and heritage attractions played a vital role in this development. Recent research demonstrates that approximately 40% of global tourism is based on heritage and cultural attractions (Kempiak et al., 2017). Furthermore, the authors reveal that the customers’ preferences are gradually shifting from passive tourism, such as conventional holidays at sea, to more intellectually demanding experiences (Kempiak et al., 2017). Additionally, the industry’s overall profits exceed more than $2 billion and account for approximately 75 million jobs globally (Childs, 2021). From these considerations, the significance of tourism and cultural heritage management is consistently growing all over the world.

Role of Heritage Attractions in Tourism

At present, cultural heritage is one of the most notable constituents of tourism and has an immense impact on the overall attractiveness of destinations. The empirical research has demonstrated that one UNESCO World Heritage Site is accountable for approximately 6,000 international tourists for European countries (Panzera et al., 2020). The vast impact of heritage sites has a positive influence on the national economies, creates jobs, and increases the cultural attractiveness of the country (Panzera et al., 2020). Thus, heritage sites also affect the cultural worldview and shape the perception of people in regard to tourist attractions (Lee et al., 2020). For instance, Lee et al. (2020) reveal that the cultural perception of tourists has significantly changed after visiting Hankok – a traditional house village in Korea. From these considerations, their positive experience of the heritage sites translates to their perception of the country, thus, increasing the attractiveness of the destination (Lee et al., 2020). Therefore, the model of heritage attractions is effective on the global scale are used in various parts of the world. Ultimately, heritage attractions play a vital role in tourism and significantly enhance the reputation of the host countries.

Tourism and Heritage Attractions in England

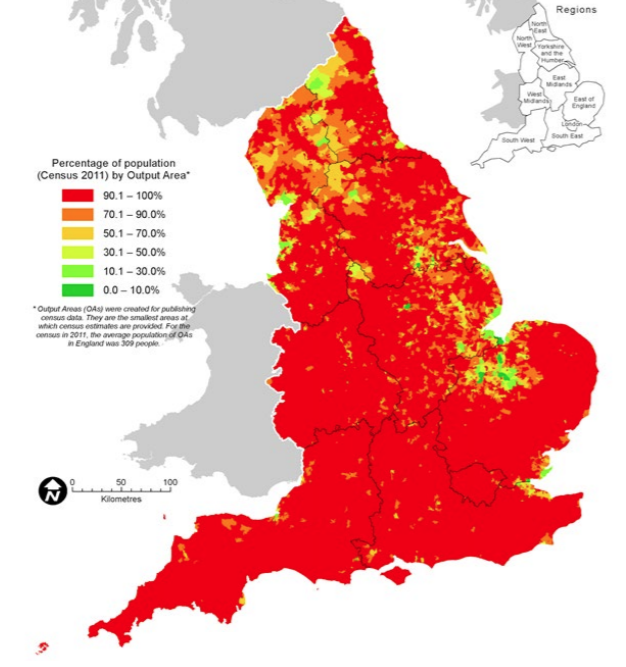

Consequently, it is essential to discuss the role of tourism and heritage attractions in the United Kingdom. While the recent consequences of COVID-19 obstruct the data collection, the public organisation Historic England provides thorough information on heritage attractions in the United Kingdom. According to the statistics, UK citizens dedicate approximately twice more time to heritage tourism compared to people from other European countries (Historic England, 2020). This phenomenon is supported by the large number of various heritage attractions in England, which appeal to both domestic and international tourists (Historic England, 2020). For instance, the density of the cultural sites and heritage assets is illustrated below in Figure 1:

Ultimately, heritage attractions play a vital role in the development of the industry, and the quantity of assets transparently reflects this tendency.

Consequently, the recent surveys also indicate the growing interest of UK citizens in heritage sites. According to the statistics, there were approximately 76 million visits to various heritage attractions in 2018 in the UK (Historic England, 2020). Furthermore, the data reveals that the vast majority of the UK citizens – approximately 95% – strongly support the preservation of historical heritage assets, and around two-thirds consider local heritage a source of pride (Historic England, 2020). Therefore, the heritage attractions shape the perception of the destination not only for international tourists but also for UK citizens.

Effect of COVID-19 on Heritage Tourism

COVID-19 has significantly obstructed the development of traditional heritage tourism globally while paving the way for digital engagement. For instance, Wang et al. (2021) compare the consequences of COVID-19 with the damage caused by SARS in 2002-2003 and estimate an approximate $1 billion economic loss for China. Furthermore, most countries implemented a similar policy of complete closure of various heritage attractions due to the risks of COVID-19, which caused significant damage to global tourism. Nevertheless, the pandemic also paved the way for additional methods to recover the tourism industry. For example, Elgammal and Refaat (2021) discuss the role of virtual tours and digital tourism in the example of Egyptian heritage sites. The authors report that virtual tours are not only effective instruments of digital tourism, but they also motivate the customers to visit the heritage sites personally at a later date, when pandemic restrictions are lifted (Elgammal and Refaat, 2021). Ultimately, the COVID-19 limitations have become a part of daily life, and organisations need to find innovative methods to attract tourists.

The Role of Technology

One of the methods to increase the visitors’ engagement with heritage attractions and mitigate the consequences of the pandemic is the implementation of innovative technologies. At present, this approach is frequently utilised in museums, art galleries, and other types of heritage attractions (Bae et al., 2020). Furthermore, the heritage sites utilise a wide array of digital methods, including virtual tours, augmented/mixed/virtual reality, holograms, and information technologies, to enhance the customers’ experience. Ultimately, technology plays a vital role in contemporary tourism and is consistently becoming more prevalent among customers.

Virtual Tours

The most popular digital approach to tourism is the virtual tour. At present, this approach utilises a large variety of methods and techniques, such as virtual museums, 360° video applications, 3D modelling, computer reconstructions, etc. (Argyriou et al., 2020; Giannini et al., 2017; Povroznik, 2018). In most cases, virtual tours refer to online methods of immersion, allowing tourists from all parts of the world to visit the heritage sites (Povroznik, 2018). Furthermore, these technologies are utilised for a large variety of cultural attractions, including museums, galleries, historical sites, etc. The various innovative approaches also allow for customer personalisation, interactive systems, educational exhibits, and other methods of customisation (Povroznik, 2018). However, the most notable advantage of virtual tours is accessibility, which allows people from all over the world to enjoy heritage attractions and sites.

Mixed Reality and Virtual Reality

Unlike virtual tours, which can be accessed from any part of the world, mixed and virtual reality approaches are frequently used to complement conventional tourism. It is essential to note that virtual tours might utilise the virtual reality approach for a more comprehensive immersion; however, the two concepts are not synonyms, and VR is commonly used as an engagement method at offline sites. In this sense, mixed and augmented reality are complementary methods that enhance the visitors’ experience (Bae et al., 2020). The research demonstrates the high satisfaction levels of MR and AR, and that tourists more frequently choose the heritage attractions with the implemented immersion systems (Bae et al., 2020). Therefore, these methods primarily enhance the visitors’ experience at offline sites, while the most notable advantage of virtual tours is accessibility from all parts of the world.

Advantages of Innovative Approaches

Despite the seeming necessity of digital approaches in the era of pandemic restrictions, virtual tours and mixed reality methods have a large variety of advantages compared to conventional tourism. The first benefit is the overall accessibility, which is significantly obstructed by the COVID-19 restrictions for offline tourism (Nanni & Ulqinaku, 2020). Furthermore, alongside the legal regulations, the research shows that a large number of people are generally afraid of crowded places due to pandemic-related deaths (Nanni & Ulqinaku, 2020). As a result, digital approaches offer many opportunities that negate the fear of mortality threat and are highly effective alternatives to conventional tourism.

Additionally, another accessibility advantage of the innovative approaches concerns the distantly located heritage sites. For instance, the geographic location and weather conditions significantly discourage tourist activity in the Canadian Arctic (Dawson et al., 2018). As a result, despite the cultural significance of the area and the immense heritage of the Inuit communities, the tourists tend to avoid the site (Dawson et al., 2018). Nevertheless, contemporary technologies allow tourists to experience notable Inuit heritage attractions, such as Arvia’juaq, from any part of the world (Dawson et al., 2018). For instance, the panosphere photo of Arvia’juaq is presented below in Figure 2:

As a result, the efforts of a relatively small group allow tourists from all over the world to enjoy the panoramas of a cultural site that is inaccessible to most people to visit first-hand.

Consequently, digital approaches cater to elderly customers and vulnerable people with disabilities. Dieck et al. (2019) investigated the perception of the virtual reality method in heritage attractions among older adults. The authors revealed that such parameters as accessibility, experience sharing, novelty, and digital progress, which allows connecting past and present, are the most significant factors for elderly tourists (Dieck et al., 2019). Furthermore, most respondents had a vastly positive experience of VR tourism and wanted to revisit the heritage sites at a later date (Dieck et al., 2019). Therefore, the innovative approaches, including virtual and mixed reality, are highly effective in providing more accessible tourism opportunities to vulnerable groups of people.

Van Gogh Museum

Finally, it is essential to illustrate the capabilities of the innovative approaches on the example of an existing virtual tour. The selected site is Van Gogh Museum located in Amsterdam and is accessible via both offline and online visits. The website of the organisation provides a complete overview of Van Gogh’s life, distributes tickets, sells merchandise, and redirects the viewers to the YouTube channel and virtual tour (VanGoghMuseum, n.d.). The virtual tour itself is supported by Google Arts & Culture, which is an online platform that partners with a large variety of cultural organisations and presents their artworks in a virtual format (“Van Gogh Museum”, n.d.). Thus, visitors can visit Van Gogh Museum from all parts of the world.

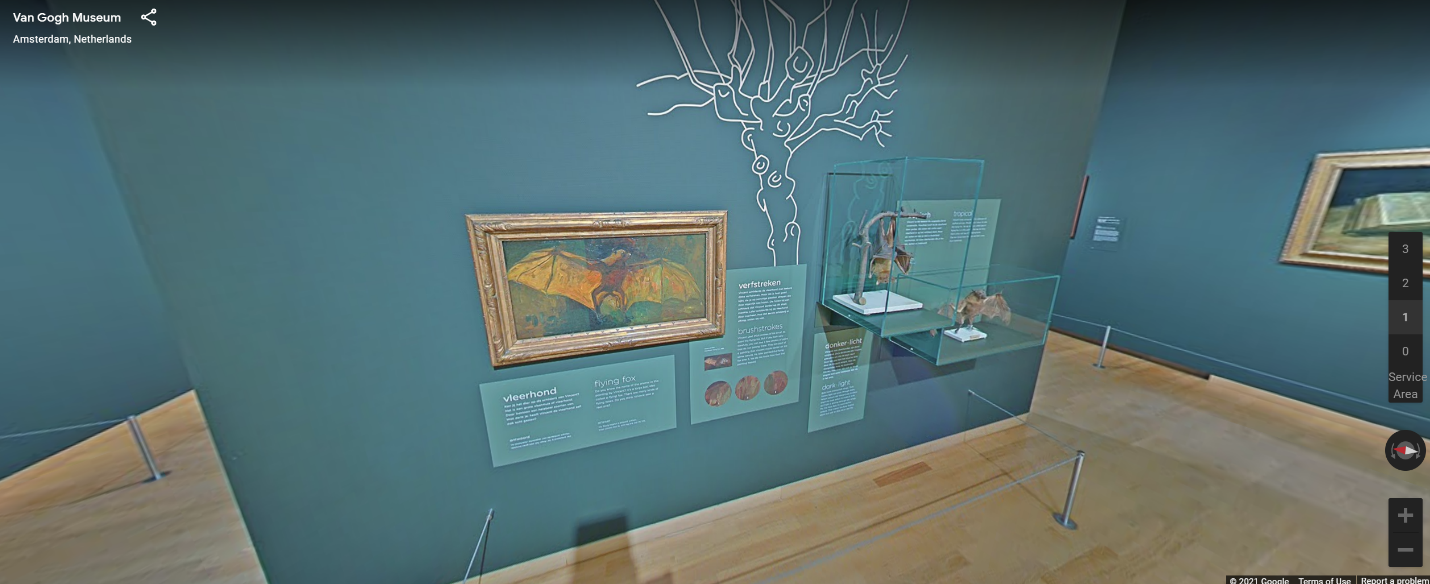

Consequently, it is essential to provide a brief overview of the virtual tour’s capabilities and explain how it enhances visitors’ engagement. The first function of the website is the exploration feature, which is enabled due to the collaboration with Google Arts & Culture. It is an interactive map that allows visitors to navigate the museum and choose the locations for panoramas manually. The example of the function is presented below in Figures 3 and 4:

The exploration function enables free navigation throughout all four floors of the museum with high accuracy. The available locations are spread approximately one metre from each other with the option to zoom in and zoom out of the frame manually. The comparison is presented below in Figures 5 and 6:

These functions allow visitors to fully immerse themselves in the virtual experience and enjoy the paintings from various angles and distances. Thus, the exploration option is the primary feature of the virtual tour that significantly enhances the visitors’ engagement in the museum.

Consequently, the website offers a large variety of additional functions. For instance, if the exploration function seems vague, the visitors can manually inspect the paintings or visit the online exhibits. The former option allows the customers to choose any artwork from the museum and receive complete information about it. Figure 7 below demonstrates the overview of the Giant Peacock Moth painting:

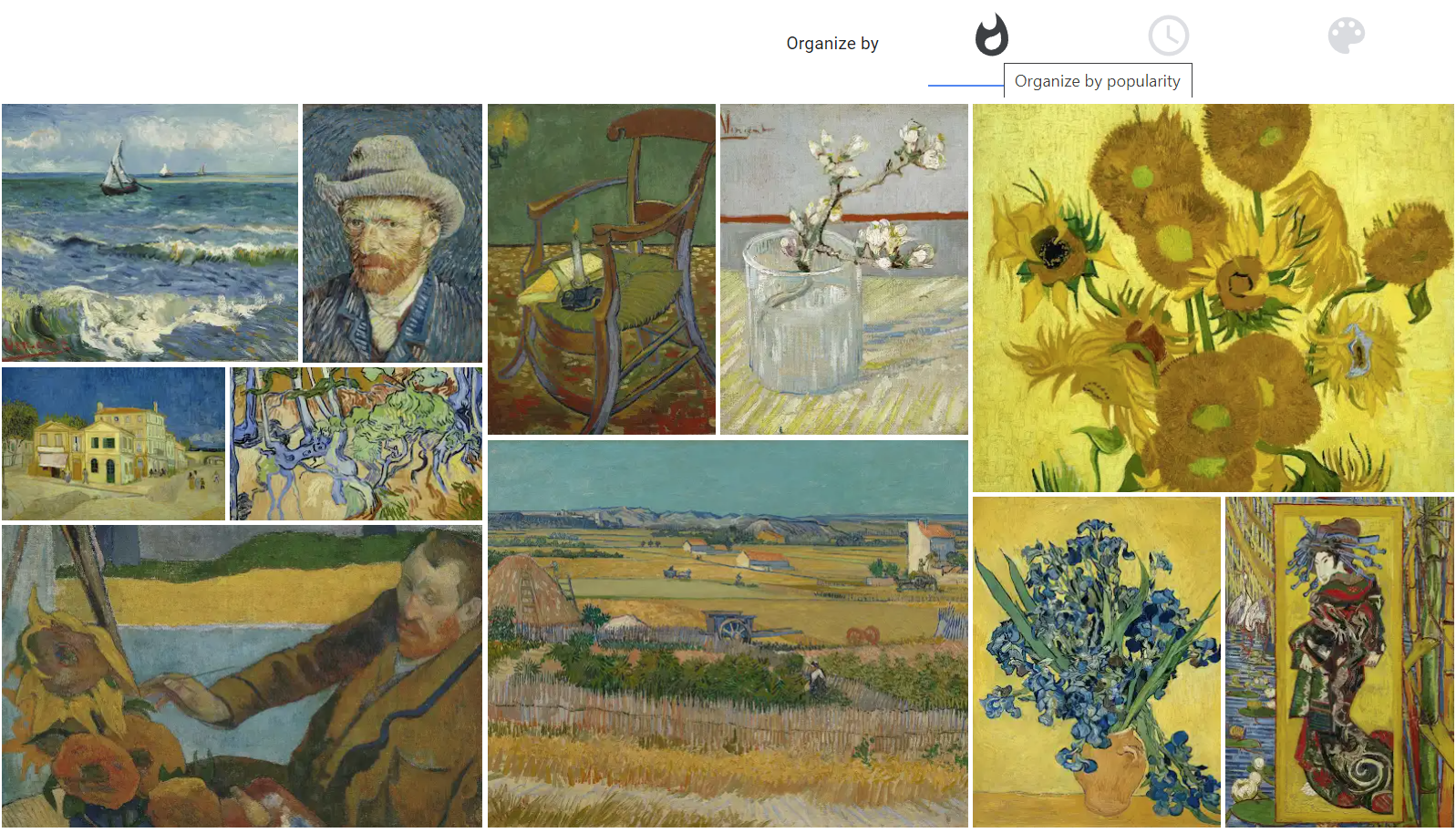

This option provides an overview of the artwork and allows customers to view it in various formats, such as online, exploration, and even augmented reality. Furthermore, the website allows sorting all the artworks in the museum based on popularity, chronology, and colour. Figure 8 below demonstrates the classification by the popularity of paintings:

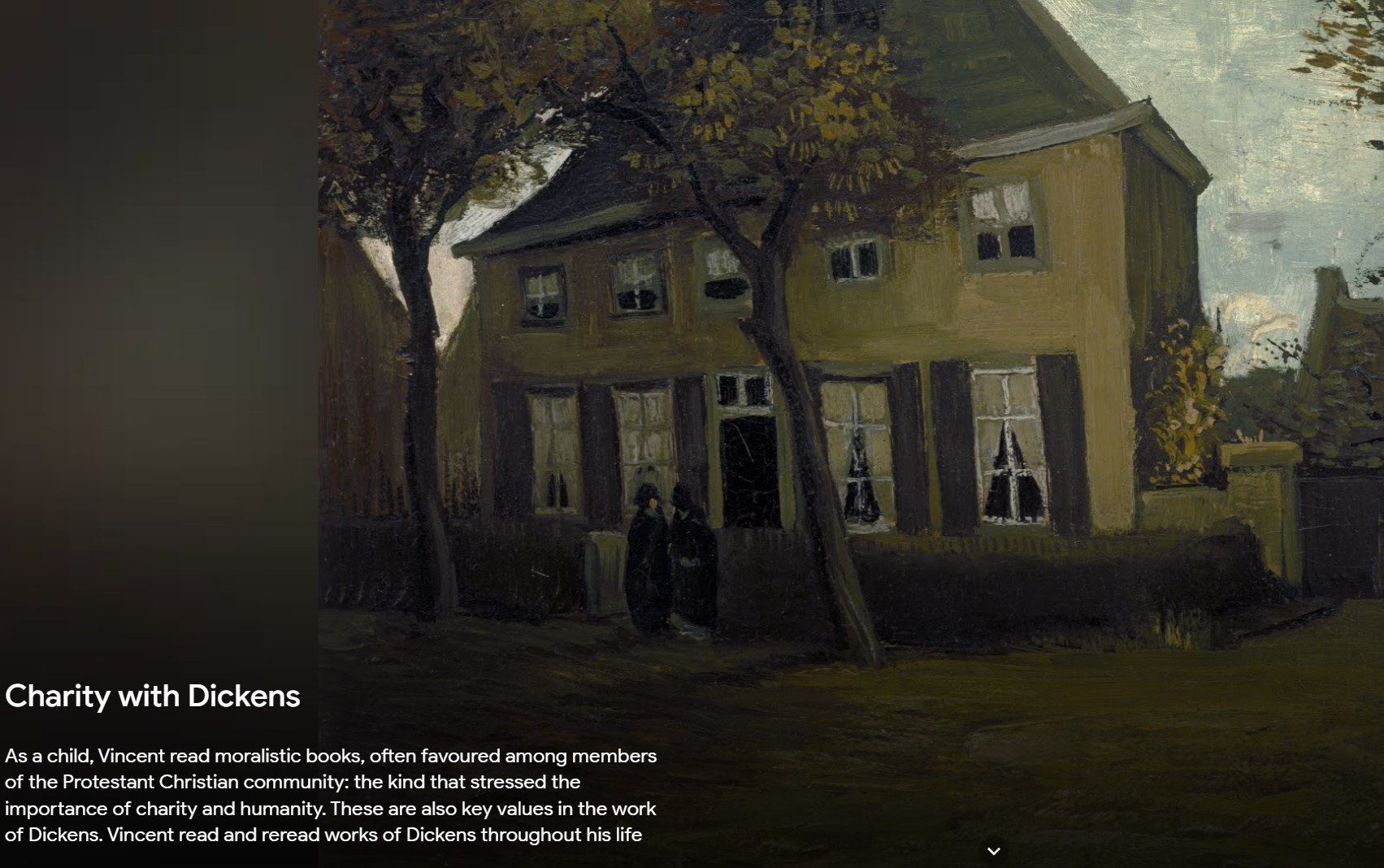

This option increases the overall understanding of the author’s art career, indicating his most popular paintings and allowing customers to comprehend the chronology. Thus, it is beneficial for educational purposes and enhances the convenience of the viewers. Lastly, the website offers online exhibits, which resemble offline exhibitions and are useful for learning more about the author’s life. The example of the exhibit is presented below in Figure 9:

Ultimately, a virtual tour is a convenient and accessible method of cultural tourism, and Van Gogh Museum transparently reflects the effectiveness of the approach.

Conclusion

Heritage attractions and cultural sites play a vital role in international tourism and significantly enhance the reputation of the destinations. Nevertheless, the recent COVID-19 outbreak has obstructed the conventional tourism approach, increasing the popularity of innovative methods, such as virtual tours and augmented reality. At present, many museums and heritage attractions offer virtual tours, which are accessible to people from all over the world. Ultimately, heritage tourism is critical to visitor economy development and might become even more relevant in the future.

Reference List

Argyriou, L. et al. (2020) ‘Design methodology for 360 immersive video applications: the case study of a cultural heritage virtual tour’, Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 24(6), pp. 843-859.

Bae, S. et al. (2020) ‘The influence of mixed reality on satisfaction and brand loyalty in cultural heritage attractions: A brand equity perspective’, Sustainability, 12.

Carbone, F. et al. (2020) ‘Extending and adapting the concept of quality management for museums and cultural heritage attractions: A comparative study of southern European cultural heritage managers’ perceptions’, Tourism management perspectives, 35.

Childs, C. (2021) How culture and heritage tourism boosts more than a visitor economy. Web.

Dawson, P. et al. (2018) ‘“Some account of an extraordinary traveller”: Using virtual tours to access remote heritage sites of Inuit cultural knowledge’, Etudes Inuit Studies, 42(1), pp. 243-268.

Dieck, M. C., et al. (2019) ‘Experiencing virtual reality in heritage attractions: Perceptions of elderly users’, in Augmented reality and virtual reality. Springer Cham, pp. 89-98.

Elgammal, I., and Refaat, H. (2021) ‘Heritage tourism and COVID-19: Turning the crisis into opportunity within the Egyptian context’, in Tourism Destination Management in a Post-Pandemic Context. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 37-48.

Giannini, M. et al. (2017) ‘WebGIS, 3D modeling and virtual tours to map, record and visualize the cultural, archaeological and landscape heritage: The VisualVersilia project’, in Proceedings of 3rd IMEKO International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. Lecce: Italy.

Historic England. Heritage and society 2020. Web.

Kempiak, J. et al. (2017) ‘The heritage tourist: An understanding of the visitor experience at heritage attractions’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 23(4), pp. 375-392.

Lee, C. K., et al. (2020) ‘The roles of cultural worldview and authenticity in tourists’ decision-making process in a heritage tourism destination using a model of goal-directed behavior’, Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18.

Nanni, A., and Ulqinaku, A. (2020) ‘Mortality threats and technology effects on tourism’, Annals of tourism research, 3.

Panzera, E., et al. (2021) ‘European cultural heritage and tourism flows: The magnetic role of superstar World Heritage Sites’, Papers in Regional Science, 100(1), pp. 101-122.

Povroznik, N. (2018) ‘Virtual Museums and Cultural Heritage: Challenges and Solutions’, in Digital Humanities in the Nordic Countries. Helsinki: Finland.

Van Gogh Museum. (n.d.) Web.

VanGoghMuseum. (n.d.) Discover the life and work of Vincent van Gogh. Web.

Wang, L. et al. (2021) ‘The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on revenues of visitor attractions: An exploratory and preliminary study in China’, Tourism Economics.