Introduction

The primary purpose of any form of taxation practiced across civilizations the world over is to raise revenue needed to finance public services. But there exist numerous tax systems that can be used to achieve this noble objective, including property tax, personal income tax, inheritance tax, sales tax, and value added tax, among others. Of particular importance to many governments is the personal income tax since it makes up a huge percentage of their revenue. In the US, for example, the personal income tax has held on as the principal source of government revenue, contributing over $927 billion in 2005 (Walker, 2006). However, many governments are unable to fund their projected spending due to inefficient tax systems that inexorably limits their revenue collection. It is the purpose of this paper to critically evaluate how a successful personal income tax system can be implemented in Hong Kong.

Dynamics of Tax System versus Tax Player Participation

The nature of relationship between the personal income tax system and the tax player is critical in determining whether governments will meet their obligations of providing services to the public. According to Minden (2009), in as much as the citizens have a duty to pay taxes to support efficient delivery of services, tax agencies are also legally, structurally and morally obligated to come up with efficient and effective tax regimes that must be seen to be reasonable to the tax players. Cameroon (2006) argues that “…the institutional practices of taxation have been subject to continuous if not constant renegotiation throughout their long history in response to the changing forms and functions of the societies they help constitute” (p. 237). This therefore implies that both the tax agency and the tax player must never be seen as separate entities if implementation of a successful personal income tax system in Hong Kong is to be achieved.

The tax system practiced in Hong Kong is normally considered as reasonably “simple and favorable to the tax player compared to that of many industrialized nations” (Graig, 1990 p. 125). The country is also ostensibly considered as a tax haven, not mentioning the fact that it has repeatedly restructured its tax system downwards to prevent other Asian tigers such as Singapore and Thailand from taking its competitive advantage (Macpherson, 2002). This means that many tax players, especially personal income tax players have greatly benefited from rebates and substantial cuts in payable taxes as the country orchestrates its strategy to woo more investors onboard. In Hong Kong, personal income tax, otherwise known as salaries tax is governed by the rules and regulations of Inland Revenue Ordinance (IRO).

In a country where the level of unemployment stands at only 4.9 percent of the total workforce, one would reasonably expect the personal income tax to be a noteworthy contributor to general revenue (Trading Economics, 2009). But this is as far as it goes. Tax experts have on more than occasion suggested that Hong Kong’s personal income tax system is in need of major reform due to a number of factors, key among being the presupposition that it is reliant on a very narrow base (Graig, 1990). A research conducted by reputable Tax consultants KPMG and documented by Wehrfrintz et al (2005) revealed that only 30 percent of the labor-force pays any personal income tax. Among the reasons advanced are that Hong Kong is predominantly a cash economy, and that many individuals in the labor force are only liable to profits tax since they are self-employed.

In view of the above, it is prudent to engage tax player participation so that the country is able to dispense its obligations efficiently and without compromising its role as the leading investment destination in the Asia-Pacific region. There exist a general feeling that the effectiveness and relationship between the salaries tax system and the tax player participation is not a balanced one even when put under the microscope of fairness and enforceability (Coulter & Heady, 1997). Arguing on the principle of Expected Utility Theory (EUT), it may be prudent to enhance the salaries tax to a level that will increase compliance since more individuals in the labor-force will definitely avoid taking the risk of non-compliance. According to Davis et al (1997), “…EUT states that “the decision maker (DM) chooses between risky or uncertain prospects by comparing their expected utility values” (p. 342). In this scenario, the decision maker may be anybody from the IRO to other tax experts, and the fundamental duty is to develop strategies that would actively engage tax players so as to realize the expected maximum value – revenue to sustain public services.

Engaging the Tax Player Participation

Various governments and tax agencies the world over have developed strategies and mechanisms to entice tax players to meet their part of the bargain – pay tax. When compliance have neither been uniform nor linear across geographical localities and countries, it is clearly evident that industrialized countries and emerging powers has performed better in this area than the developing world (Cameroon, 2006). This may be a function of elaborate and efficient tax collection techniques coupled with harsh penalties for tax evasion (Panbeirra & Lukas, 2008). However, it does not mean the rich countries enjoy zero-tolerance to non-compliance. To the contrary, cases of massive tax noncompliance have been reported in many of these countries, including the UK, US, China, Hong Kong, Japan, among others.

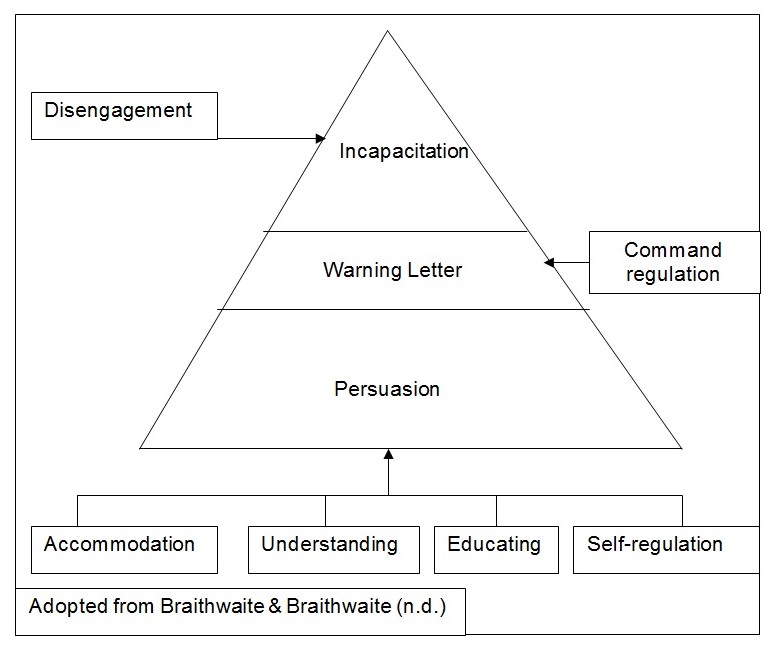

The fundamental understanding is that tax players are actively engaged by relevant authorities so that they may comply with particular tax regimes. It is within public domain that tax players must be actively engaged in funding public services by duly paying their taxes on a willing basis (Minden, 2009). However, governments and tax agencies may not necessarily agree with public thoughts, and some may use orthodox means while others end up using unorthodox means to attain compliance. In this perspective, the enforcement pyramid strategy to regulation practiced by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) can serve as a model that can be emulated by government tax agencies to engage tax player participation, therefore ensuring compliance. According to Braithwaite & Braithwaite (n.d.), the “regulatory staff prefer the low-cost option of persuasion first and escalate to more deterrence-oriented options (and ultimately to incapacitation) as less interventionist strategies successfully fail” (p. 1). The model is depicted by the illustration next page.

Coming closer to practice, Hong Kong uses a hybrid persuasion and deterrence-oriented options to engage tax player’s participation, and hence compliance. For instance, the Inland Revenue Ordinance is mandated to use personal assessment to relieve the tax liabilities of individuals under special circumstances. To use an example, a personal assessment may inarguably lessen the tax payable by a person salaries tax in addition to paying other taxes such as profits tax or property tax. This serves to engage a tax player into actively willing to pay taxes. Married couples living together are also eligible for personal assessment under Hong Kong tax system (Ho, 2009).

According to the figure above, it is prudent to argue that accommodation, understanding, education and self-regulation can also be used persuasively in the process of engaging the tax player to participate willingly towards the country’s revenue base, thereby contributing to the implementation of a successful personal income tax system (Braithwaite & Braithwaite, n.d.). Indeed, it is the unwavering conviction of the Inland Revenue Department-Hong Kong (IRD-HK) that continuing tax player education coupled with modern programs aimed at ensuring tax knowledge can indeed enhance voluntary conformity by employers and tax players (Ho, 2009). E-Seminars aimed at offering guidance on such practices as correct filling of tax returns and available tax benefits, including rebates and other tax reductions for compliance can also be used to engage tax player participation (Smith & Macpherson, 2009).

The deterrence-oriented option has also been effective in engaging tax players’ participation, especially to individuals who engage in shady deals. It is a weapon of choice in many countries around the world, including Hong Kong (Ho, 2009). According to official Hong Kong’s documents, “The effective operation of Hong Kong’s simple tax system with low tax rates requires a high degree of compliance by tax players” (GovHK, 2009 p. 1). It is therefore within the mandate of the Commissioner to administer appropriate punitive measures on noncompliance depending on the nature of offence committed and degree of culpability. To implement a successful personal income system in Hong Kong, such powers can be used to net offenders, and either institute prosecution or demand additional tax in form of penalties. With such powers to prosecute tax offenders, one can bank on the dynamics of the Prospect Theory since few tax players would want to make a risky decision that will see them go to jail or penalized for noncompliance.

Comparisons and Amendments: US versus Hong Kong Tax Systems

The US and Hong Kong tax systems might never share many things in common; but at least they share a foreboding reality that their revenue collection capacities are dwindling by the day albeit for totally different reasons. In the past, experts have argued that Hong Kong relies on a very constricted base for revenue collection, with other labeling the island a tax haven (Graig, 1990; Smith & Macpherson, 2009). Although the tax system has been largely efficient, and investors applauding it due to its light tax burden, the ripple effect is that the country has “too few [revenue sources] and too many people asking for something” (Wehrfrintz et al, 2005 para. 1). Indeed, the only taxable items in Hong Kong are property, personal income, and profits tax – nothing more.

In the US, “current projected revenues are not sufficient to fund projected spending” (Walker, 2006 p. 1). Such a statement must astonish many coming from a country whose individual income tax totaled $927 billion in 2005 (Walker). The US tax system is largely complicated, dipping its tentacles in nearly every aspect of life. Indeed, the US tax system is so multifaceted that tax players end up paying tax to four diverse levels of government, including local, municipal, district and township governments. Other entities such as state and federal governments must also be included in the tax regime (Tyler, 1990). Although the US had in excess of 138 million tax players as of 2006, and uses a progressive tax structure, it is still faced with the burden of reforming its tax structure due to revenue deficits – the same problem currently bedeviling Hong Kong (Boartz & Linder, 2006). Its not therefore in order to argue that the US income tax system can be replicated by Hong Kong to entice tax players into willingly and actively paying taxes.

In view of this, it is evident that both tax systems have agreeable strengths as well as deep-rooted weaknesses. Well-calculated amendments may therefore awaken Hong Kong’s personal income tax back from its deep slumber and ensure that tax players will be willing and ready to pay their due taxes, including salaries tax. But first there is need to get a historical perspective of the problem. Most of these obsolete tax systems found across East Asia, and that exempt almost every member of society from the tax net were conceived out of raw competition for investors (Wehrfrintz et al, 2005). While the US and other European countries were fast expanding their tax networks, the Asian countries with the exemption of China were busy cutting down on their revenue base by exempting populations from paying taxes, with others like Hong Kong slashing the salaries tax to an average of 15 percent, reviewed annually. Other countries such as South Korea started creating welfare states similar to those found in Nordic countries such as Sweden, not in full realization that these countries were expanding their tax revenues while the Koreans were discouraging their citizens from active participation (Bernedi & Profeta, 2004; Wehrfrintz et al, 2005). There lay the problem.

To deal with it, tax players need to be actively engaged to pay taxes once more. It is imperative for concerned stakeholders to engage the tax player by using a multiplicity of techniques and methodologies so that they can comply with the tax regimes on a willing basis. An effective model for engaging tax player participation must focus on first trying to offer positive incentives to the tax players to induct the fundamental principle of ‘self-will’ before using coercive means on errant tax evaders. Indeed, income tax deductions should never be seen as a direct coercive tax on citizens; rather, it should be viewed in the light of a free-will offering. In Hong Kong, tax players are likely to heed the call when they are made to realize that, due to the historical hullabaloos, “the richest 4 percent of the population contributes 85 percent of all personal tax and fewer than 30 percent of the workers pay any income tax at all” (Wehrfrintz et al, 2005). In essence, they need to understand that a broader revenue base transforms into lower rates for services (Schulz, 1991).

It is evidently clear that lessening the tax deficit within the present personal income tax structure in Hong Kong must entail discovering new and creative administrative and legislative strategies. This must be done in a manner that is fair, enforceable, and reduces negative influences on the economy (Walker, 2006). The current personal income system in Hong Kong has failed on all two of the above principles since it is neither fair nor does it reduce negative effects on the economy. As already mentioned, only 30 percent of active labor-force pay any salaries tax at all, creating a strain on service delivery (Wehrfrintz et al, 2005). As such, the future about Hong Kong’s personal income tax can be best accomplished by reforming the current narrow income tax system through streamlining it to attain equity, adequacy and neutrality (ITEP, 2008). This way, all tax players will be encouraged to participate through the currently used method of either persuasion or deterrence-oriented option.

Tax players can also be enticed to participate actively to the personal income tax system through the introduction of incentives such as fiscal exchange, amnesties, tax credits and social safety net (Alm et al, 2008). Although Hong Kong’s unemployment rate is minimal, a social safety net such as unemployment insurance can reinforce positive beliefs about tax fillings on the minds of the unemployed. When such people eventually get employed, they will continue with the trend, and will become willing tax players in terms of participating actively in remitting their taxes or divulging the nature of their works. This is essential if the country’s income tax system is to engage tax player participation. Inarguably, according to Alm et al (2008), a target tax credit offers the highest returns on compliance than a social safety net.

Conclusion

While many countries across the world identify the urgent need to modernize their ailing and obsolete tax systems, the commitment to take decisive steps varies widely. The challenge for many countries located in East Asia, including Hong Kong, is to embrace change in their tax systems with unwavering vigor so that not only will politicians be bound by law and moral obligation to account for tax evasions, but taxes should also be imposed on populations for the first time (Wehrfrintz et al, 2005; Coulter & Heady, 1995). A viable and vibrant personal income tax system is important not only in Hong Kong but also in any other countries since it contributes a huge chunk of the national cake. Such a tax system needs to be streamlined and simplified to have the capacity to serve both the country and tax players with equity, adequacy and neutrality (ITEP, 2008). Above all, it is the duty of all people residing in the country to know they have a moral and legal obligation to pay taxes.

List of References

Alm, J., Cherry, T., Jones, M., & McKee, M (2008). Encouraging Participation in Tax

Filling via Tax Credits and Social Safety Nets. Paper Presented at IRS Research Conference. Web.

Braithwaite, V., & Braithwaite, J (n.d.). An Evolving Compliance Model for Tax Enforcement. Web.

Bernedi, L., & Profeta, P (2004). Tax Systems and Tax Reforms in Europe. New York NY: Routledge.

Boartz, N., & Linder, J (2006). The Fair Tax Book: Saying Goodbye to the Income Tax and the IRS. Harper Collins Publishers.

Cameroon, A (2006). Turning Point? The Volatile Geographies of Taxation. Antipode, Vol. 38, Issue 23, pp. 236-258

Coulter, F., Heady, C (1995). Fiscal Systems in Transition: The Case of the Czech Income Tax. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 47, Issue 6

Davis, J., Hands, W., & Maki, U (1997). Handbook of economic Methodology (Eds). London: Edward Elgar

GovHK (2009). Tax Reduction through Personal Assessment. Web.

Graig, J (1990). The Hong Kong Tax System: An Overview. Web.

Ho, P.K (2009). Hong Kong Taxation and Tax Planning. Pilot Publishing Co.

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (2008). Tax Principles: Building Blocks of a Sound Tax System. Antipode, Vol. 48, Issue 2

Macpherson, A (2002). Hong Kong to Scrutinize Singapore Tax Strategy. Web.

Minden, C (2009). Understanding Taxes (Real World Math: Personal Finance). Cherry Lake Pub.

Panbeirra, C.D., & Lukas, B.D (2008). The basic principles of income Tax Systems: Asian Context: Journal of Business, Vol. 48, No. 3

Scholz, J.T (1991). Cooperative Regulatory Enforcement and the Politics of Administrative Effectiveness. American Political Science Review, Vol. 85, pp. 115-136

Smith, D.G., & Macpherson, A (2009). Hong Kong Taxation: Law and Practice, 2008-2009. The Chinese University Press.

Trading Economics (2009). Hong Kong Unemployment Rate. Web.

Tyler, T (1990). Why People Obey the Law. New Haven: Yale University Press

Walker, D.M (2006). Individual Income Tax Policy: Streamlining, Simplification, and Additional Reforms are Desirable. (GAO-06-1028T). Viewed 3 February 2010 from EbscoHost Database

Wehrfrintz, G., Adams, J., Lee, B.J., Seno, A.A., Vitug, M., & Kolesnikov-Jassop, S (2005). Tax the People. Newsweek (Atlantic Edition), Vol. 145, Issue 13, p. 31-33.