White Oak

Common name: white oak

Scientific name: Quercus alba

Physical description: with each species, height varies. Usually reaching a mature height of 50 to 75 feet. Able to reach heights of 100 feet. 40 to 70 feet in width. Simple, lobed, alternate leaves with rounded tips. With a diameter of 3 to 4 feet, it often grows to 80 to 100 feet (White Oakquercus Alba). Fall foliage is colored like wine, finally turning brown. White oak trees frequently keep their leaves until the middle of winter, which adds to their beauty.

Life cycle/reproduction: grows on arid slopes and highland forests. In most of the state, except for northwest Iowa. Healthy, well-drained soil produces the best growth—the ability to adapt to challenging soil conditions. White oak has a long lifespan and grows slowly (around 1 foot each year) (350-500 years) (White Oakquercus Alba).

What eats it: when food is scarce, many tiny animals may also consume the leaves and twigs of oak trees in addition to their acorns. Squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, opossums, raccoons, and woodrats are a few of these creatures.

How is it ecologically significant? Acorns are one of the most acceptable food sources for animals and are collected, stored, and consumed by birds, rodents, and hoofed browsers. Additionally, several bird species consume the leaf buds, and Deer like to eat the entire tree.

Northern Red Oak

Common name: northern red oak

Scientific name: quercus rubra

Physical description: red oak often grows to heights between 70 and 80 feet and diameters between 2-3 feet (Northern Red Oak). Depending on the weather, fall foliage can be red, orange-red, or deep reddish brown.

Life cycle/reproduction: optimum growth occurs in wet, well-drained soils. Tolerant of challenging soil conditions. When young, red oak may grow up to 2 feet per year, which is a modest growth rate (Northern Red Oak). The average lifespan of Northern Red Oaks is 200 years. However, some have been discovered to be as old as 400 years.

What eats it: the primary dietary preferences of blue jays, wild turkeys, squirrels, small rodents, whitetail deer, raccoons, and black bears are acorns from this tree. In the winter, deer also graze on the buds and twigs.

How is it ecologically significant? Red oaks are producers. In addition to converting carbon dioxide to oxygen, it employs photosynthesis to generate energy for itself. The tree offers many different kinds of birds, houses, and places to nest. Many different species of wildlife eat the acorns that the tree produces.

Red Maple

Common name: red maple

Scientific name: acer rubrum

Physical description: the medium to a large deciduous tree known as the red maple is called for its recognizable crimson fall foliage, fruits, blooms, and twigs. As the tree ages, its smooth, grey bark changes to scaly, dark grey bark. Its leaves feature three to five pointed lobes with serrated edges ranging from 2.5 to 4 inches.

Life cycle/reproduction: flowers begin to develop in March and April and blossom in the early spring. Winged fruits are airborne and develop between April and June. Usually, seeds begin to bud after ten days. Trees can start producing viable seeds at four and typically do so every other year. Stump growth can return following a fire or mechanical disruption. Red maple trees typically live for 60 to 90 years, although they have been known to live for 200 (Plant database).

What eats it: red maples provide food, shade, and a place to build nests for animals. Rabbits and Deer consume the delicate shoots and leaves, while squirrels and other rodents devour the fruits.

How is it ecologically significant? The biology of bees and other pollen-dependent insects may benefit from the early pollen generated by red maple because of its widespread dispersion and quantity.

Silver Maple

Common name: silver maple

Scientific name: Acer saccharinum

Physical description: the opposing, palmately lobed leaves. There are five long, acutely pointed lobes on each leaf. The sinuses on the leaf are V-shaped. The color of the leaf is green on top, but when you look at the underside, you see a silvery-white hue. A silver maple’s trunk may have three to five feet in diameter.

Life cycle/reproduction: although the typical silver maple may live for over 130 years, most only survive for a maximum of 35 years in cities (Silver Maple). The tree proliferates, and its wood is fragile and feeble. Frequently develops several trunks or branches from a low point on the trunk into numerous, hefty branches. If mechanically harmed, young trees reproduce profusely. If repeated floods have harmed the root system, it can swiftly rebuild. However, this tree is readily destroyed by fire because of its thin bark and shallow root system.

What eats it: the seeds of the silver maple are consumed by wild turkey, bobwhite quail, finches, squirrels, eastern chipmunks, and wood ducks. Eastern cottontails and white-tailed Deer consume the stems and leaves. Squirrels consume the buds, and beavers eat and gnaw on the bark. The silver maple tree is a hangout (roost) for various birds. They include grackles, European starlings, brown-headed cowbirds, and red-winged blackbirds.

How is it ecologically significant? The hydraulic lift caused by the silver maple helps to disperse soil water. It extracts water from the deeper soil layers and releases it into the dry higher soil layers. Many other plants around, as well as the tree itself, will benefit from this.

Tulip Poplar

Common name: tulip tree

Scientific name: liriodendron tulipifera

Physical description: a large, quickly growing tree that can grow to 150 feet or taller in the wild. In cultivation, it may reach heights of 70 to 90 feet and a spread of 35 to 50 feet. Leaf: These oddly shaped, vivid green leaves range in size from 3 to 8 inches (Tulip tree liriodendron tulipifera). Yellow or golden yellow is the hue of autumn.

Life cycle/reproduction: in ideal circumstances, trees can blossom and generate seeds as early as ten years old, which is more often the case at 15-20 years old. For at least 200 years, seeds are produced. Although there is a lot of seed production, only 5–20% of the seeds are viable. For up to 8 years, seeds are still viable in the seed bank (Tulip tree liriodendron tulipifera). Although it reacts to sunlight and heat, germination is accelerated by frequent cold dormancy spells.

What eats it: small black snout beetles known as yellow poplar weevils, commonly referred to as sassafras weevils or magnolia weevils, attack tuliptree, sassafras, and magnolia trees. Adults chew characteristic holes in the leaves that are the size and form of bent rice grains.

How is it ecologically significant? The fast-growing nature of this plant makes it a good choice for speedy establishment in the landscape. A broad canopy provides bird nesting locations, and the leaf litter that falls to the forest floor enriches the soil. Deep and widespread roots help retain soil in place.

American Beech

Common name: American beech

Scientific name: fagus grandifolia

Physical description: this tree is between 60 and 100 feet tall, with a 112 to 4 feet wide trunk and an oval crown. The trunk is often short and thick, and the crown is big in open places. The crown is smaller, and the trunk is longer and limbless in forests. While the bark of twigs is dark and glabrous, the bark of the trunk and bigger branches is smooth and light gray. Young leafy shoots are dark with occasional thin yellowish hairs. Alternate leaves are oblong-elliptic to oblong-ovate in form and are 212–6 inches long and 3–4 inches broad (Plant database). Their edges include widely spaced incurved teeth. Each lateral vein on a leaf ranges in size from 10 to 14.

Life cycle/reproduction: beech typically starts producing a significant number of seeds when it is around 40 years old and can produce a lot by the time it reaches 60. A good beech seed harvest is generated every two to eight years. As far north as the north coast of Georgian Bay, the American beech may be seen growing across southern and central Ontario. It is a medium-sized tree that develops slowly and has a lifespan of at least 200 years.

What eats it: beechnuts, the nuts that beech trees produce, are an essential source of animal protein and fat. Beechnuts are a common food source for wild turkeys, white-tailed deer, squirrels, chipmunks, and other creatures.

How is it ecologically significant? The black-capped chickadee and other songbirds, including insects, can find refuge and habitat in the American beech. In addition, various birds and animals, such as mice, squirrels, chipmunks, black bears, deer, foxes, ruffed grouse, ducks, and bluejays, eat beechnuts.

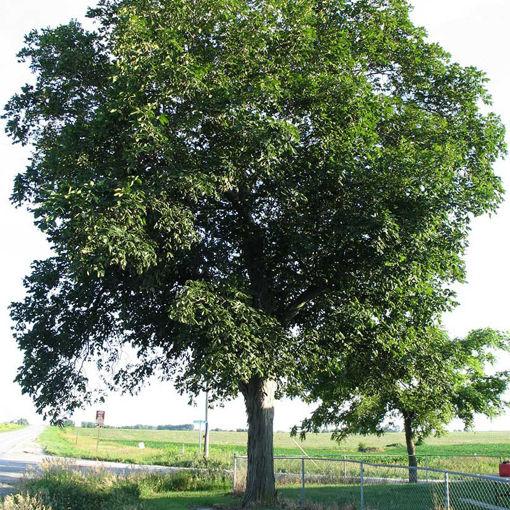

Hickory

Common name: hickory

Scientific name: Carya

Physical description: hickories often attain a height of 30 meters (100 feet) with a lengthy taproot. Compound leaves have three to seventeen leaflets apiece, and some species’ compound leaves become brilliant golden in the fall.

Life cycle/reproduction: midway through April, flowers begin to appear. Catkins are green-hanging bunches of flowers that produce pollen and are exclusively male. Female flowers grow in spikes and produce fruit. Hickories are a part of the walnut family, and both people and animals enjoy the fruit of the shagbark hickory. The fruit is a nut that breaks apart when mature and has a hard outer shell. Around 40 years old is when snag bark hickories achieve maturity and begin to produce seeds. While a shagbark’s lifespan is typically 200 years, some longer-lived species can continue to produce seeds well into their 300s (the University of Nebraska-Lincoln | Web Developer Network).

What eats it: every autumn, black bears, foxes, mice, chipmunks, squirrels, rabbits, and several birds eat the nuts.

How is it ecologically significant? Hickories serve as a food source for various animals, including numerous kinds of squirrels, wild turkeys, songbirds, black bears, rabbits, raccoons, and foxes, which consume nuts. Hickory wood is utilized as fuel for house heating and is significant for the environment.

American Holly

Common name: American holly

Scientific name: ilex opaca

Physical description: smooth and light white-grey in hue, the bark is. The green, leathery leaves of this plant have spine tips. The American holly typically reaches heights of 15 to 25 feet, but when cultivated in an environment with enough moisture, it may reach heights of 60 feet. Its trunk can grow 20 inches in diameter (Plant database).

Life cycle/reproduction: the American holly starts to bloom in the spring, usually from April through June. The females only produce fruit, which ripens from September to December before remaining on the tree until winter. When a tree is four to seven years old, it starts to produce seeds. They will start to produce greenish-white blooms at this age. The pollination process, which aids reproduction, is carried out by insects like ants, bees, and moths.

What eats it: over 18 different kinds of birds, including wild turkeys and mourning doves, consume the berries of American holly. The plant is consumed by squirrels and other small animals and infrequently by cattle and Deer. American holly trees are the home of the red-cockaded woodpecker, an endangered species. Forests harmed by ocean spray can be repaired by planting American holly. It occasionally faces competition with pines and hardwoods for nutrients, sunshine, and water.

How is it ecologically significant? American holly offers refuge to animals in the winter and nectar to butterflies and insects in the spring and summer.

Virginia Pine

Common name: Virginia pine

Scientific name: pinus virginiana

Physical description: Virginia pine is a scraggly, straggling evergreen that grows to be 15–40 feet tall and eventually has a flat top (Pinus virginiana). The reddish-brown trunk gives way to unevenly spaced outstretched branches. Cones have prickly-like appendages that make them feel sharp to the touch. A short-needled tree with a long-spreading crown that is open, wide, and irregular shape; frequently a shrub.

Life cycle/reproduction: an individual tree typically lives between 65 to 90 years (Pinus virginiana). Trees have an uneven crown of protruding, long branches that branch upward and downward.

What eats it: some animals, including turkey, quail, chipmunks, and rabbits, consume nutritious pine seeds off the ground. Other birds, such as nuthatches, chickadees, and grosbeaks, eat pine seeds from the cones while still on the trees.

How is it ecologically significant? The species is essential to animals, especially songbirds, who are known to nest in the tree and eat the ripe seeds (including the northern bobwhite quail). Woodpeckers prefer Old Virginia pines for breeding, and numerous small animals, including squirrels, eat the seeds and find cover in them.

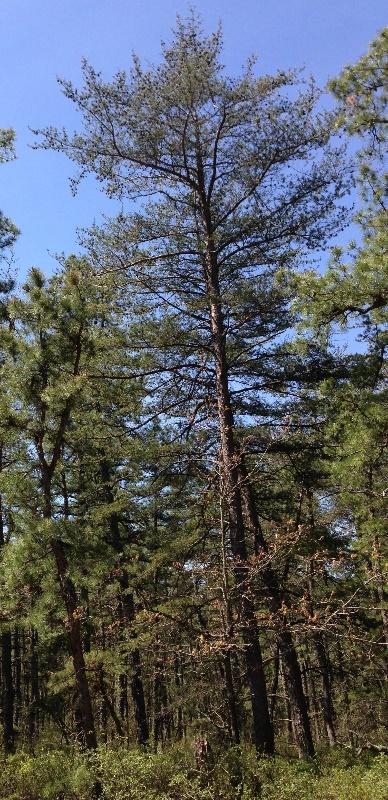

White Pine

Common name: white pine

Scientific name: pinus strobus

Physical description: a sturdy, priceless tree. Delicate, blue-green needles grouped. Ideal windbreak or screen is fond of damp, well-drained soils. Grows up to 135 feet in the wild and 50 to 80 feet in the landscape with a 20 to 40-foot spread (Pinus strobus).

Life cycle/reproduction: only a few seeds can germinate in the second year; the majority either germinate or die after the first year. There is no seed banking, and none of them make it to the third year. Often lives to be 200 years old and has a 450-year life span (Pinus strobus).

What eats it: both birds and small animals consume the seeds. Gophers feed on the roots, and rabbits and animals occasionally eat the leaves of young plants. Bear cubs frequently climb these trees to flee peril.

How is it ecologically significant? Numerous animal species can find food and home among eastern white pines. Songbirds and small animals consume Eastern white pine seeds. Numerous animals consume the bark, including cottontails, white-tailed deer, and snowshoe hares.

Eastern redcedar

Common name: eastern redcedar

Scientific name: Juniperus virginiana

Physical description: evergreen Eastern Redcedar trees can reach heights of 30 to 40 feet. The tree leaves are glandular and resemble scales (Eastern redcedar Juniperus virginiana). The bark is a reddish-brown tint and peels off in long, fibrous strips, frequently turning ashy gray where it is exposed. Late winter or early spring is when the little, pale blue-green flower clusters reach maturity.

Life cycle/reproduction: the Red Cedar may live anywhere from 100 to roughly 300 years, depending on whether it is in its native environment. Although mature red cedar trees almost always yield some seeds, good crops only come about every two to three years (Eastern redcedar Juniperus virginiana). Although many are eaten and spread by animals, the cones do not open and will stay on the tree throughout the winter. In February and March, the majority of the remaining cones are distributed. In the fall, mature fruits are often gathered by hand-stripping or shaking onto canvas. Seeds can be kept as cleaned seeds or dried fruits.

What eats it: animals like pheasants, Cedar wax wings, and other songbirds eat the fruit of the tree. The seeds are eaten and dispersed by birds. In the winter, many animals use it as food and refuge.

How is it ecologically significant? Animals that live on land can also find refuge when it rains, thanks to the foliage’s canopy.

Christmas Fern

Common name: Christmas fern

Scientific name: Polystichum acrostichoides

Physical description: it is a sturdy, leathery fern with lustrous, year-round green fronds. A crownless rootstock produces clusters of fronds 1-2 feet long (Plant database). Fertile fronds are taller. The texture is medium to gritty due to the formerly separated fronds with pointy pinnae. In the early spring, silvery fiddleheads appear.

Life cycle/reproduction: Christmas ferns go through two morphologically distinct generations during their life cycle: sporophyte and gametophyte. Spores—tiny reproductive organisms – are created during sporophyte formation. They encourage the formation of gametophytes. Gametophytes produce male and female reproductive cells, sperms, and ova. A perennial plant is the Christmas fern (life span: over two years).

What eats it: The Christmas Fern is significantly more noteworthy because it is an evergreen plant. White-tailed Deer may consume the evergreen fronds during brutal winters when there is not much else to eat. Wild turkey and spruce grouse may consume the young fronds in the spring.

How is it ecologically significant? Ruffed Grouse eat a lot of Christmas Fern throughout the fall and winter. Several bird species, including ovenbirds and veery, have reportedly used the Christmas Fern’s overwintered fronds as a springtime nesting location.

Virginia Creeper

Common name: Virginia creeper

Scientific name: parthenocissus quinquefolia

Physical description: Virginia creeper is a woody, tenacious vine that may reach heights of 3 to 40 feet before dropping off; the height it can reach depends on the building it is climbing. Virginia Creeper climbs using disk-shaped tendrils that attach to bark or rock. It is up to 6 inches long, coarsely serrated leaves with five leaflets, with three or seven leaflets on rare occasions, and radiates from the petiole’s tip (Plant database). The leaves provide early fall color, which becomes a bright mauve, scarlet, and purple. Unnoticeable springtime blooms are little, greenish clusters.

Life cycle/reproduction: usually propagated by seed. However, branches that contact the ground will root; clusters of greenish blooms; and blue-black berries.

More than 35 bird species, including thrushes, woodpeckers, warblers, vireos, mockingbirds, and other songbirds, consume the berries of the Virginia Creeper.

How is it ecologically significant? It grows well in wet soil, in either partial shade or full sun. Mice, skunks, chipmunks, cattle, deer, and most birds all consume this plant. Animals may use Virginia creepers as a cover and a place to nest. Virginia creeper is very useful for preventing erosion.

Mayapple

Common name: mayapple

Scientific name: podophyllum peltatum

Physical description: the only two leaves and one flower on the mayapple, which blooms in the axil of the leaves, make it unique. Mayapple has flashy, obtrusive leaves that are big, twin, and shaped like umbrellas. When the plant reaches its full height of 1-1 1/2 feet, they open up to a width of 6-8 inches after remaining closed while the stem lengthens (Plant database).

Life cycle/reproduction: despite having a longer growing season than other spring ephemerals, mayapple is a long-lived perennial that is sometimes considered a spring ephemeral. Both vegetative propagation and seed reproduction are possible, although vegetative reproduction requires more effort (Mayapple). Huge colonies are established, and both blooming and non-flowering stalks are produced.

Box turtles and maybe small mammals eat the fruits, and the seeds travel through their digestive systems.

How is it ecologically significant? Numerous species in the area, including Deer, turtles, and many tiny mammals, depend heavily on mayapple fruits for their nutrition.

Cinnamon Fern

Common name: cinnamon fern

Scientific name: osmundastrum cinnamomeum

Physical description: Osmundastrum cinnamomeum, sometimes known as cinnamon fern, is a native fern to Missouri that grows on shady ledges, bluffs, and damp, swampy soils along streams, particularly in the state’s eastern Ozark region. Grows typically in clumps to a height of 2 to 3 feet, but with sufficient hydration, it may reach 5 feet (Ferns of the Adirondacks: Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum Cinnamomeum)). Early in the spring, separate, spore-bearing, stiff, fertile fronds emerge and swiftly become brown.

Life cycle/reproduction: By using a rhizome, which develops creeping branches that extend out in opposing directions, this species is capable of vegetative reproduction. Only the ends of the stems are covered in fronds, which eventually join together to create a ring known as a “fairy ring.” It can also reproduce sexually through spores, in which the prothallus forms in 7 weeks and the juvenile frond appears in another 14 weeks.

What eats it: grazing animals like cattle and caterpillars may eat the foliage.

How is it ecologically significant? Animals do not rely heavily on cinnamon ferns as a food source. The downy wool from these ferns has been used as a nest lining by hummingbirds and Yellow Warblers, while Ruffed Grouse are said to eat the fiddleheads.

Works Cited

“Eastern Redceda Rjuniperus Virginiana.” Eastern Redcedar Tree on the Tree Guide at Arborday.org, Web.

“Ferns of the Adirondacks: Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum Cinnamomeum).” Adirondack Ferns: Cinnamon Fern – Osmundastrum Cinnamomeum, Web.

“Northern Red Oak.” The Morton Arboretum, Web.

“Pinus Strobus.” Pinus Strobus (Eastern White Pine, North American White Pine, Northern White Pine, Soft Pine, White Pine) | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, Web.

“Pinus Virginiana.” Pinus Virginiana (Scrub Pine, Spruce Pine, Virginia Pine) | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, Web.

“Plant Database.” Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin, Web.

“Plant Database.” Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin, Web.

“Plant Database.” Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin, Web.

“Plant Database.” Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin, Web.

“Silver Maple.” The Morton Arboretum, Web.

“Tulip Tree Liriodendron Tulipifera.” Tuliptree Tree on the Tree Guide at Arborday.org, Web.

“White Oakquercus Alba.” White Oak Tree on the Tree Guide at Arborday.org, Web.

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln | Web Developer Network. “Hickory, Bitternut.” Hickory, Bitternut | Nebraska Forest Service, Web.

“Mayapple.” Wisconsin Horticulture, Web.