Abstract

The idea of a child having to deal with, and finally succumb to a life-threatening disease is difficult for any one of us to understand. Certainly, it may be viewed as a flawed justice for a child to be struck by a terminal illness. Nonetheless, this does happen and all that is left is for mankind to do is come up with suitable strategies that can be used to manage the pain and suffering experienced by these young children. This study, named Terminal Illness: Understanding How a Child’s Perspective Could Help Ease the Burden of Suffering, aimed at exploring how techniques such as empathy and listening to the child’s perspective could help provide better a quality life to the terminally ill children, in addition to helping the family and caregivers ease the burden of saying goodbye to the sick child.

The analysis of the interviews brought several interrelated themes based on the objectives of the study as well as the questions that guided the study. The underlying themes resulting from the analysis of qualitative data revealed a direct correlation between listening to a child’s perspective and quality of life led by the terminally ill child. The study revealed that mothers exhibit a clearer understanding and internalization of the child’s perspective than fathers; this can be attributed to the traditional sex-role socializations. Through the study, it was revealed that learning to identify with the perspective of a terminally ill child was perhaps one of the best therapies that could be used to improve his or her quality of life.

The study also revealed that empathy had an immense role to play in reducing the suffering undergone by the terminally ill children. This is because when the children felt they were being listened to it helped them open their world to others. Empathy also made the child feel loved, cared for, and accepted by society. In the study fathers exhibited a shallow understanding of how empathy could be linked to the child’s perspective while mothers misconstrued empathy to mean sympathy. All underlying themes point to the fact that effective listening was vital in improving the quality of lives of terminally ill children as it increased the process of bonding between the child and caregivers. In addition it gives the child a chance to express his or her worries and emotions about the process of dying.

Introduction

Background

Being diagnosed with a terminal illness is perhaps one of the most foreboding nightmares for mankind, young and old. The thought of realizing that you are in the final lap of life due to a fatal illness such as advanced Cancer, full blown HIV/AIDS, and many other diseases can be terrifying to say the least. But the painful truth is that these diseases do exist, and have infected and affected many. It is estimated that over 33 million people are currently infected by these life threatening illnesses globally, thereby requiring palliative care (Doyle, Hanks, Cherny, & Calcan, 2005). The task of taking care of a dying person is not easy. The most experienced physicians may find it daunting to initiate emotionally laden conversations about palliative care with their terminally ill patients. This is especially true when their patient is a child in the final days of life.

But what does palliative care entail? Nelms (2004), states that this type of care focuses on the relief of anguish, psychosocial support, spiritual support, and closure in the final days of life. It entails showing empathy and care to a terminally ill person with the aim of improving his or her quality of life before the final day. It involves not only taking care of the terminally ill but also their families who may be suffering emotional and psychological anguish. Up to ten family members may be actively involved in the care of a dying individual (Doyle, Hanks, Cherny, & Calcan, 2005). In all circumstances, early identification, faultless assessment, and treatment are key ingredients of palliative care. It also aims at making the dying person realize he is a normal human being, and to live as actively as possible until the final resting day.

Young children with life limiting illnesses deserve to enjoy a normal life, with the same choices as their adult peers living with the same conditions. They deserve to depart with dignity and pride when their end comes. It is fundamental that family members and caretakers look at the child’s perspective at such a crucial time in their lives. While the same principles can be drawn regarding end of life management among adults and children, significant differences regarding their needs do exist (Rousseau, 2000). Sheetz and Bowman (2008), palliative management for children represents a unique, though closely correlated field to adult palliative management. For example, there are a wide variety of pediatric conditions causing death before the attainment of adulthood, many of which are unusual. The, palliative care of a child may extend over many years as opposed to that given to an adult basically because the time span of many pediatric diseases tends to take longer than those for adults. Hence it is vital for the child’s perspective to be given maximum attention.

Child’s perspective

The concept of a child’s perspective has continued to receive increasing attention in many child related programs since the 1990’s (Skivenes & Strandbu, 2006). This is largely related to the new found view of the child, where more emphasis is given to the involvement and contribution of children. The political, social, cultural and even emotional attention directed towards children in recent times is an active indicator that children are expected, and have expectations themselves to be considered active participants. Skivenes and Strandbu (2006), the emphasis on child’s perspective has the potential to mobilize children toward a position of equal standing. Arguably, an important struggle for children is to be distinguished as visible subjects, not passive objects.

A Child’s perspective, as shown above, can consequently be used in palliative care of children with terminal illnesses. Positive results will be reflected when care and treatment are done from the perspective of the child, realizing that the child is a visible subject with set expectations regarding his own life and the surroundings to which he is part of (Skivenes & Strandbu, 2006). A child with terminal illness will feel loved and cherished by those around him, including family members and caregivers, if his participation and contribution in the family or social structure is well respected despite his condition. This will impact positively on his quality of life despite the stark knowledge that he is in the final lap of life due to a terminal illness. It will help in lifting the burden shouldered by family members and caregivers.

Review of Related Literature

Introduction

Terminal illnesses are a major cause of alarm the world over, not only for children, but also adults. The illnesses continue to strike unsuspecting families, leaving a trail of hopelessness, suffering, and anguish. The illnesses attack despite the progress that has been achieved in modern medicine. The illnesses come with heavy economic burden and adverse effects to the parties involved (Black, 1998). The most common progressive terminal illnesses include cancer, HIV/AIDS, progressive neurological illnesses such as Down syndrome, and other disorders that affect vital organs of the body. Most of these diseases have no known cure; hence most intervention measures concentrate on the relief of suffering (Cherny, 2005).

Cherny (2005) says that the alleviation of anguish, maximization of quality of life until the end day, granting of comfort in death should be the primary goals of patient care with life-ending diseases. Relentless suffering on the part of the individual with a terminal illness undermines the value of life he has left. This study sets out to evaluate how the relief of suffering can be achieved on the part of the dying child by using counseling techniques such as empathy and listening to the child’s perspective. It aims at addressing one of the core issues affecting children with life threatening diseases – trying to improve the quality of their lives with techniques and procedures that will interconnect family members and caregivers to the child’s perspective.

Children with Terminal Illnesses

The notion of children dealing and finally succumbing to a terminal disease is difficult for any us to discuss. But no matter how much we want to deny that this happens, it is a reality that children are infected by incurable diseases just like their adult counterparts (Nelms, 2004). They die of HIV/AIDS, Cancer, and many other incurable diseases that also affect adults. These children experience suffering and pain coming from the cumulative effects of the progressive ailment, invasive procedures and processes, treatment, and psychological distress.

Cancer is credited to be the leading cause of non-traumatic fatality in children. Statistics reveal that over 25 percent of all children diagnosed with cancer will eventually die (Eilertsen, Reinfjell, & Vik, 2004). According to World Health Organization statistics, around 75 percent of children born with cancer are able to survive to adulthood in the US and Europe. Globally, 80 percent of all cancer cases found in children in developing countries, late or non diagnosis of the disease ensures the death of more than one in every two pediatric cancer cases (WHO, 2006). Cancer is emerging as the leading cause of childhood death in the Middle East, South America, and West Africa.

Families taking care of terminally ill children need trained support from the very onset of the diagnosis. This is because the needs of a sick child are divergent from the needs of an adult sufferer (Beaver, Luker, & Woods, 2000). In many families, the dying children spend the majority of their remaining time, in the comfort of their home, and surrounded by members of the family, pets, and their special belongings (Small & Rhodes, 2000). When family members are trained to offer palliative care, the child can comfortably remain at home for as long as it takes, alleviating the need to going back to hospital for palliative care. During the last days of life, some children and family members find the reassurance of the hospice care more comforting. According to WHO (2006) many terminally ill children found in these hospitals and hospices have cancer.

The terminally ill child is taken care of by many family members, including the mother, father, and other close family members while at home. While abundant research has been conducted to explore child and family experiences, and the coping mechanisms within these types of environments, the focus has never been on father’s participation in providing care to the terminally ill child (Wolfe 2004). Traditional sex-role socializations can best explain this phenomenon, whereby women are seen as the primary caretakers of children, especially when sickness arises, while men are conditioned to be the breadwinners. It is in these situations that it is vital for gender to be a none issue when comes to parenting a child with a terminal illness. When both parents show love and empathy towards the terminally ill child, the child feels loved. There is a gap in the role of fathers and the link between finding need to help fathers to facilitate empathy. For men that do experience difficulties in playing their roles as care-givers to the terminally ill; the focal point should be trying to alleviate the suffering of the child. The child will feel more loved and cared for if both parents show responsibility, care, and understanding towards the child’s perspective.

Child’s Perspective in Life-limiting illnesses

Coping with a terminal illness can be a very distressing situation for anybody. It becomes more distressing for those involved when a child has a terminal illness. Some children undergo a great deal of pain and suffering as they try to fathom what is really wrong with their bodies, and the transformations happening inside of them (Kreicbergs, Valdimarsdottir, Onelov, Henter, & Steineck, 2004). Older children are able to grasp the seriousness of their illnesses by the reactions of family members and others near them. The child’s anxiety levels and fears at any age can be heightened by the perception that he or she is not been told the truth about their illness. Children have a way of knowing the truth they will often detect inconsistency in information and the utter avoidance of answers to the questions they pose to their parents and others around them. As already mentioned, children want to be distinguished as visible subjects, not passive objects (Skivenes & Strandbu, 2006).

A parent can not be faulted for wanting to shield their child form the knowing the truth. In most instances, the natural response for parents and friends is to try and protect a dying child from the possible impact of the diagnosis. (Sheetz & Bowman, 2008), what and how much to disclose to a child suffering from a terminal illness is dependent on a number of variables, including individual characteristics of the child and his family, the family structure, culture and ethnic orientation, and available support. As such, the child suffering from a terminal illness may find he has been kept in the dark not because the parent wants to, but because of the many variables involved.

Families, friends, and caregivers should always keep in mind that acknowledging and respecting the child’s perspective is crucially important in trying to improve the life of the terminally ill child. More emphasis should be given to the involvement and contribution of the afflicted child in trying to manage the terminal illness. As stated before families and caregivers must understand that the terminally ill child is expected, and expects to be considered an active participant in the whole process (Skivenes & Strandbu, 2006). The quality of life of a terminally ill child can be improved if care and treatment are administered from the child’s perspective.

A child’s perspective is different from that of an adult. A child with a life threatening disease may perceive his or her life and those around him in a totally different manner than the adults might want to imagine (Stanton, Downham, Oakley, Emery & Knowelden, 1978). Caution should be taken when discussing the illness with the child to avoid unnecessary anxiety and fear. This is why it is important for family members to undergo some kind of counseling so they can learn counseling techniques to deal with child when breaking the news to them.

Counseling and the Child’s Perspective

Counseling in palliative care and management can be described as a skilled consultation between a professional caregiver and the terminally ill patient in which each draws on the experiences and knowledge of the other in order to offer assistance to the patient with any physical, psychosocial or spiritual issues that they would like to explore. The experiences and knowledge of the individual offering the counseling services exists as a result of formal training and experience, self-awareness and an active awareness of the child’s culture and value system. (Sauer, Lopez, & Gormley, 2003).

Looking at the definition of counseling itself, one will realize that it can be quite helpful to counsel a terminally ill child since it counseling caters to the patient and in this case to the child’s perspective. It is a situation where the child will be allowed to express his thoughts and fears knowing that there is someone who is listening to him or her with empathy and care. Terminally ill children may want to talk to somebody about what is happening to their bodies, about the meaning of their sickness, their relationships with others, their fears, hopes, and their beliefs (Sahler, Frager, Levertown, Cohn, & Lipson, 2000). The counselor can be a parent, close family member, or a professional caregiver, who will look at the experiences from the perspective of the child, not from his own perspective (Mancuso, 2004). It is critical that family members and caregivers learn to give the terminally ill child a chance to contribute to their own treatment offering a framework where he can freely express his thoughts, feelings, and opinions regarding his condition.

Counseling should be extended not only to the terminally ill patient but to the family members as well. Family members suffer the pain and anguish of having to watch their loved ones being consumed by an illness that they know can not be reversed. It is a painful experience which deserves counseling from a professional caregiver (Cohen, 1999). The family members of the terminally ill child need more help than the child himself since they rescind around the stage of denial until they are forced to face the harsh reality that the child has a life ending disease.

It is often the family members themselves that offer the best counseling services to the terminally ill child since they spend more time with the child than anybody else. If the child has been hospitalized, then the role can be taken on by a professional caregiver at the hospital. There are several counseling techniques that can be used to improve the quality of life of a dying child (Doyle et al, 2005), especially when they are used in relation to the child’s perspective. For purposes of this study, empathy and listening as counseling techniques will be discussed.

Empathy

Plainly put, empathy entails identifying with, and understanding the situation facing another person, his feelings, and motives. Empathy ignites passionate feelings of genuine and sadness and concern for somebody who is faced with misfortune (Hoffman, 2001; Gallagher, 1989). In addition, empathy entails a close understanding between people who seem to relate to one another. When applied to the study context, empathy entails showing understanding to the needs of the terminally ill child especially in relation to his or her own perspective. Family members and caregivers must show that they understand the terminally ill child’s experiences as if they were at the center of the child’s world (Sheetz & Bowman, 2008). This involves showing the child that he is understood from his internal frame of reference, with all the feelings, thoughts, cognitions, and understandings that a child has.

Empathy can be effectively used to interconnect with the child’s perspective as the family members and caregivers will have to look at the needs and feelings of the child from their perspective and then try to make the best of that situation. Goldman, Hain and Liben (2006), the family members and caregivers have to experience and understand the world of the suffering child as if it were their own, from the same vantage point of the dying child. This will help improve the quality of life for the terminally ill child.

Listening

Perhaps one of the most important ways of helping a terminally ill child is to listen to them. People feel loved when they are given attention; the child will also feel loved and cared for when those close to them offer their attention. Listening to the child’s perspective is one of the most effective ways to enhance the quality of life of a dying child (Rousseau, 2000). A child in this kind of situation should always have someone to talk about his fears, hopes, anger and sadness without the burden of trying to be brave. Being left alone at the hour of death is a common fear not only for children but also for adults.

For listening to be effective in improving the quality of life of a terminally ill child, it must be done from the perspective of the child rather than from the perspective family members or caregivers (Lester et al, 2001). At all times, a child’s wishes or thoughts must be respected. The family members and caregivers must also be honest and open with the child, allowing him to discuss his or her fears and answering their questions. A dying child will feel less anxious if he knows that he has someone who is willing to listen to him, someone to support and love him. It is a basic fact of life that dying children, or adults for that matter, will feel isolated and afraid if they sense that there is no one willing to listen to them. Offering the terminally ill hope through empathetic listening will have significant impact enabling the terminally ill to search for positive aspects of their lives at times of great distress (Itzhaky & Lipschitz-Elhawi, 2004).

Listening goes hand in hand with communication. Mcgehee and Webb (2007), one achieves effective communication through simple planning and control. It is important for family members and caregivers to be mindful of their communication with the terminally ill because some conversations may be detrimental to the well being and quality of life of the dying.

Theoretical Framework

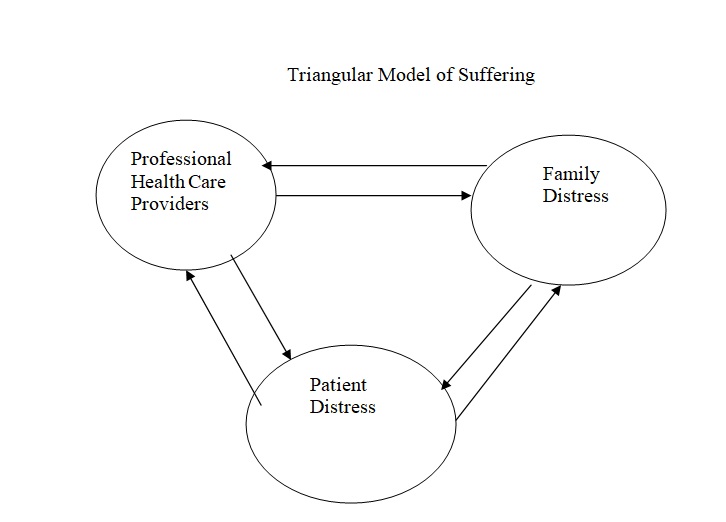

The diagnosis of a life-threatening ailment affects everyone involved, from the dying child, to the family members, and caregivers themselves (Cherny, 2005). Feelings of dread, confusion, reservation, and even isolation are common in these situations. The interrelationship that exists between the patient with a life-threatening condition, his or her families, and the health care professionals can be best described by the Triangular Model of Suffering. These terminal illnesses affect the patient; patients with advancing disorders may experience acute pain and other physical conditions that substantially diminish their quality of life. Young children may particularly be affected by such a situation since they can not fathom why they should be under such pain. This is why different palliative care and management approaches must be followed for children and adults (World Health Program Pain and Palliative Care Communication Program, 2006).

Cherny (2005), some patients suffering from terminal illnesses undergo intense psychological anguish to the point of losing the meaning of life. This is especially true for patients with advanced cases of cancer. The psychological distress affects individuals with life-threatening diseases due to the realization that no one, not even their close family members or their physicians can save them from eventual death. The reactions of family members often proceed in a grief progression, including preliminary shock and disbelief that can last for days to weeks to months, culminating in acceptance of the harsh reality (Hay, Haywood, Levin, & Sondheimer, 2002). In the terminally ill child, the distress is often under-detected and therefore under-treated, leading to momentous impact on the part of the individual and family.

On the second front, the terminal illness affects the family and loved ones. They feel great distress, and are engulfed by anxiety due to the knowledge that their loved one is in the process of demise (Cherny, 2005). The families bear the burden of care, not mentioning the fact that they stand witness to the deteriorating situation of their loved one, both physically and emotionally. To complete the model is professional caregivers, who are also affected by the illness they attend to the dying on medical grounds these experiences may challenge their medical and emotional reserves (Cherny; Perry, 2009)

This model thereby concludes by arguing that the suffering of these groups is innately intertwined to the point that identifiable suffering of any one of these groups may intensify the suffering of the other groups (Feudtner, Feinstein, Satchell, Zhao & Kang, 2007). The model can then be best employed in this study since it deals with alleviating the suffering of one group, which inevitably makes other groups follow suit in suffering. When the quality of life of the child is uplifted through the use of various cousnseling techniques, it eases the pain for the child, the family and caregivers. But when the terminally ill child continues to suffer, and his or her quality of life continues to decline, then the family as well as the professional caregivers suffer to. Below is a diagrammatic expression of the model.

Methodology

Study Design

Chenail, George, Wulf, Duffy, and Charles (2009), qualitative research design is the best tool to be used when the aim of the study is to gather an in-depth understanding of human characteristics and behavior, including the reasons that govern such behavior. This is the objective of this study; to understand how empathy and listening to the child’s perspective could help in providing a better quality of life at the end. The design is best at investigating the why and how, not just the what, where, and when. Qualitative research design is often used to formulate policy, and in the area of program evaluation research as it is able to offer answers to specific vital questions more efficiently than quantitative approaches.

Statement of the Problem

It is a sad fact of life that children often get sick. Many times though, they usually recover and recommence their usual lifestyles. But there are times when children are stricken with life-threatening diseases. This is undeniable injustice, but all that parents, physicians, and other caretakers can do is to make the child comfortable and ensure that his or her social, emotional, physical, and spiritual needs are met in the most rational manner possible (Beaver, Luker, & Wood, 2000). Although losing a close member of the family has never been easy, the death of a child comes as a tragedy to the family concerned, thereby making it one of the most bizarre experiences a human being can undergo. The stress, grief and guilt is overwhelming for all concerned, but it must be endured (Howarth, 1972)

Processes and techniques have been developed to deal with these kinds situations. Techniques, such as psychotherapy, have been clinically tested and found to be effective in reducing the suffering of the terminally ill child and their families. The use of compassionate, engaged, empathetic listening to the terminally ill, attention to process, and other cognitive behavior processes such as problem unraveling and reframing are requisite competencies for palliative care (Perry, 2009). It is the intent of this study to evaluate how empathy and listening to the perspective of a terminally ill child may help provide better quality of life during the end days. The study would also like to explore how taking the child’s perspective can help the family, caretakers and the child ease the burden of suffering.

Objective of the study

Broad Objective

The general objective of the study is to explore how palliative counseling techniques such as empathy and listening to the child’s perspective can be important elements in the palliative care of the terminally ill child at the end of life.

Specific Objectives

- Is the child’s perspective helpful in palliative care?

- Establish techniques through which the child perspective can be used to stimulate the terminally ill child towards living a quality life.

- Establish procedures and mechanisms through which both the families and care providers of terminally ill children can benefit from hearing the child’s perspective.

- Come up with initiatives by which the child’s perspective can be used in establishing or reinforcing the already existing policy frameworks regarding palliative care for terminally ill children.

Research Questions

The study will be guided by the following research questions

- Q1: What are the attitudes and perceptions held by families and caregivers regarding the child’s perspective?

- Q2: Does the child’s perspective serve to increase or decrease the pain and suffering of the terminally ill child and those around him or her?

- Q3: What is the level of awareness about various counseling techniques such as empathy and listening among families living with terminally ill children and the physicians taking care of them?

- Q4: How would improved knowledge and understanding of the techniques contribute to interconnectedness between the families, caregivers, and the terminally ill children’s perspectives so as to raise their quality of life?

Value of the Study

The value of this study cannot be underestimated. Terminally ill children, families, and care givers continue to suffer in anguish not knowing how available counseling techniques can be interconnected with the child’s perspective to improve the quality of life of the child at the end. This can also ease the burden that is shouldered by those around the child. This study’s goal is to come up with a body of knowledge to enlighten those troubled with how interconnectedness works to the benefit of the terminally ill child and the caregivers. In addition, this research aims at coming up with policy mechanisms through which care for the terminally ill children will be enhanced with the use of counseling techniques available today. While efforts are being made to apply the techniques of palliative care to the terminally ill children, pediatric palliative care has not been broadly recognized as a specialty. Palliative care is of growing concern to societies as the world grapples with how best to provide empathetic end-of-life care to a growing section of the population, children included (Carter & Levetown,).

Target Population

The target population for this study will include parents and family members caring for terminally ill children. These may either be males or females but must be knowledgeable enough to give an account of how they have been caring for the terminally ill, especially in relation to counseling and communication components of the relationship. The target population for this study will also include professional caregivers offering help to people with terminal illnesses, especially children. Preference will be made to family members and caregivers dealing with cancer patients. As Eiser (1993), states many terminally ill children suffer from Cancer.

Methods of data collection

Primary data will be collected through the use of covert observation of the relationship between the terminally ill children on one hand and family members and caregivers on the other. However, covert observation will mostly be limited to the hospital setting. Observation is a way of gathering information by noting physical characteristics, behavior, and events in a natural setting (Lynes, 1999).

Personalized interviews will also be conducted for the purposes of collecting primary data on parents and other family members entrusted with the care of the terminally ill children. Focus will be laid on the type of relationships that exist between the family members and the terminally ill child, their experiences, the attitude of the sick child towards his or her condition, and any other discussion that may help to bring out the interrelationship that exists between the terminally ill child and the family members, and if these relationships have helped improve the quality of life of the child. Interviews are effective in exploring perspectives of a particular thought, program, or situation (Boyce & Neale, 2006).

Study Limitations and Constraints

Although there are many life-threatening diseases inflicting children today, this study will be limited to studying the quality of life of cancer victims due to constraints of time and resources. Therefore, while the design may provide the basis for generalization of the study findings with regard to children suffering from life-threatening Cancer, the same cannot be done on other life-threatening conditions such as HIV/AIDS and Sickle cell. A more comprehensive study would have shed more light on the relationship between empathy and listening to the child’s perspective on one hand, and the provision of a better quality life on the other hand.

Results

Introduction

This study’s goal was aimed at exploring how empathy and listening to the child’s perspective can help provide better quality of life for the terminally ill child. The study also explored how taking a child’s perspective into consideration could be of assistance to the terminally ill child, the family members, as well as the caregivers in terms of easing the burden of saying goodbye. To that effect, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted on families entrusted with offering care to the terminally ill children. The interviews also targeted the professional caregivers offering medical and counseling assistance to the terminally ill children.

The in-depth interviews were centered around trying to understand the multifaceted thought processes, behaviors, attitudes, values, and interpersonal dynamics that form the relationships between the above named respondents and the terminally ill children, focusing mostly on the children’s perspective. Covert observations were also carried out in a hospital setting, with an explicit purpose of trying to establish how the relationships between the caregivers and the suffering children affect their quality of life. The analysis of the interviews brought several interrelated themes based on the objectives of the study as well as the questions that guided the study. The questions for the in-depth interviews were structured to capture the personal philosophies of the respondents regarding the terminally ill children, their objectives towards the children, as well as their personal experiences.

The underlying themes that resulted from the analysis of the qualitative data revealed a direct correlation between a child’s perspective and the quality of life led by the terminally children before their deaths. Some mothers explained that they experienced ups and downs with the children, and the only way that had helped them out of the problem was by identifying with their children’s needs and, according to one mother, “putting myself in my child’s shoes.”

In this study, women exhibited clearer understanding and internalization of the child’s perspective as opposed to their male counterparts entrusted with the care of their terminally ill children. Again, this has to do with traditional division of labor, which perceived men as breadwinners and women as caregivers. The men exhibited limited understanding of the importance of the child’s perspective. When asked about how he identified the needs facing his 10 year old child suffering from advancing cancer, one father responded:

“Actually, I don’t know what to do so I buy him things it doesn’t help I don’t know what to say. He would rather talk to his big brother. I feel helpless and out of control to tell you the truth… I feel frustrated, angry and hopeless…..I don’t have control and I don’t know what to do to help the situation….”

When the same question was posed to a nurse she responded with the following:

“All we can do is keep them comfortable and listen to them. We try and meet their needs to the best of our abilities. It’s especially draining when you’re dealing with the very young….the babies and toddlers…. you come to work knowing you will give them what you have and at the end of the day you hope you have helped in some small way. It takes it’s toll when one of them dies but it happens and we manage. It can be very somber in the unit on those days.”

Empathy and the Reduction of Suffering

Nearly all respondents – family members and caregivers – were in agreement that empathy had an immense role to play in reducing the suffering of the terminally ill children. The themes that were interpreted from the qualitative data revolved around the concept that empathy made the terminally ill children to open up their worlds to other people entrusted with their care. Another theme was that empathy made the terminally ill to feel loved, cared for, and accepted, in addition to the fact that many respondents viewed empathy as a natural medicine for the suffering.

Fathers and other male relatives exhibited a relatively shallow understanding of how empathy could be linked to the child’s perspective to bring the desired effect. Some mothers and other females also misconstrued empathy to mean being overly protective of the terminally ill children to a point of not sharing important information about the sickness with the child. This did not help the situation, with such respondents confiding that they are often psychologically tormented by the state of the suffering child, and don’t see themselves adapting to the harsh reality no matter what. When asked about how she deals with the emotional requirements of her dying child, one mother had this to say:

“ I will never forgive myself for what she is going through…. God is not fair I’m not sure he exists right now what my baby is going through is horrible…she’s so beautiful, how can this happen to my little girl. She is all the center of my world and I can’t bare the thought of losing her.

When asked the same question another mother of terminally ill son respond:

“ I ask myself, what did I do to make this happen. What have I done to deserve this kind of punishment? I try to be put on a happy face for him but I am so angry and hurt I have no idea how to help him. I can’t even help myself. I find myself asking the nurses to take care of things I should be able to do for him…but I can’t.”

Explanations like the ones above were substantial, signifying that respondent perceived empathy to be synonymous to sympathy. To be empathetic, individuals needs to understand the world of experiences of the terminally ill children as if they are at the center of the children’s world (Lair, 1996). The underlying theme that arose out of the interviews with the care providers was that empathy skills were essential for one to be able to offer his or her services to the terminally ill children. Indeed, the care providers were all in agreement that empathy skills should be taught to all the family members taking care of the terminally ill children.

Listening and Reduction of Suffering

All the underlying themes regarding listening that arose from the study pointed to the fact that effective listening was crucial in improving the lives of the terminally ill children. Indeed, great listening was ranked higher than spiritual nourishment during the end-of-life days. Many reasons were given for the choice, including the fact that effective listening increased the bonding between the terminally ill child and the family members, not to mention the fact that it presented the terminally ill the chance to express their feelings in regards to the process of dying. This goes a long way to improve the quality of life of the dying children. Though many respondents were good listeners, the same could not be said of communication. Many respondents confirmed in the study that they were unable to effectively communicate their values and thought processes to the terminally ill children for fear that they could hurt their feelings. When asked how he related with his daughter when she was in severe pain, one father responded:

“I have to leave …. I cry…then I try and get myself under control. There are days when I don’t want to come because I can’t do anything for her. I hold her hand and tell her daddy loves her and that he’s sorry. If God would let me I would take her place. I love my little girl and there isn’t anything I can do to make things better. I feel like a failure.”

When asked the same question another father responded:

“I’m not good at this… I don’t know what to say or do when the pain gets bad. I can see it on his face. I like it best when I just sit with him and the drugs are working and I don’t have to say anything. I feel helpless… Everyday is a struggle for him… I don’t want him to suffer anymore.

Discussion

Caring for a terminally ill child can be a daunting task for anyone. Family members and caregivers should know how to relate to the child’s perspective when giving palliative care to the dying children (Bearison, 2006). Learning to identify with the child’s perspective is the only way if the quality of life of the child is to be improved.

According to the triangular model used in this study, it is clear that all are interrelated – the child, the family members, and the professional caregivers (Cherny, 2005). It therefore follows that if one unit in the whole system is not happy, or is not functioning well; all the other units are affected. This study revealed that family members who had difficulties adapting to the harsh realities of the terminal illnesses led a very difficult life. Their denial of the sad reality made the lives of the terminally ill even more difficult. In view of this, policy makers should come up with strategies and policies through which individuals entrusted with the care of the terminally ill children are offered basic counseling skills to enable then cope with the trauma.

A child undergoing terminal illness will definitely feel loved and cherished by those around him, including family members and caregivers, if his contribution to the family and social structure of which he is part of respects his views and attitudes towards the condition he is in (Skivens, & Strandbu, 2006). According to the results, this principle needs to be reinforced with the philosophies of family members entrusted with the care of the terminally ill children. The study revealed that some family members were overly protective of the child, effectively denying them the chance to be active in their own right. This scenario can be changed by offering basic palliative skills and education to those all of those involved with taking care of the terminally ill child.

Consequently, it is necessary that society comes up with ways by which these children in their last phase of their lives can be given dignity and freedom of choice to be happy whatever that means for them not their for parents or caregivers. This study begins to reveal that empathy and listening to the terminally ill child’s perspective can help provide a better quality life at the end of life.