China is considered to be one of the most populated countries in the world. Moreover, the country has been holding the world’s leading position in this field for a long time. Therefore, the issue of Chinese demographic policy is one of the most important. The problems that are associated with the size of the population are especially acute in this country. In fact, at this stage of economic and demographic development, it is impossible to raise living standards without solving these issues.

In recent years, there have been numerous heated discussions among the expert community and in the Chinese media about the apparent need of revising the “one family – one child” policy. In addition, researchers also discuss the possible consequences for the country’s development in connection with the abolition of strict birth control. Economists and demographers expressed particular concerns about the consequences of this policy, which has lasted for almost forty years. According to researchers, “the policies have a far-reaching impact on population size, fertility rate, sex ratio, age structure, family size” (Wang, 2017, p. 21). As a result, China has decided to change its demographic policy and allow each married couple to have two children.

Background

First of all, before discussing the consequences, it is important to review the history of that rule. The Chinese government was forced to legally limit family size in the 1970s when it became clear that vast numbers of people were overwhelming the country’s land, water, and energy resources. This demographic policy was called “one family – one child,” or just “one child,” policy. The Chinese leadership associated the fulfillment of socio-economic and political tasks with limiting the growth of a huge population because taking care of such a big population was difficult. In order to limit population growth, the country began to implement new family-planning rules from the mid-1960s with an ever-increasing tightening of it.

At the beginning, the authorities allowed families to have three children. Then, after a few years, parents were offered to have no more than two children, and, from the beginning of the 1980s, they began to consider an exemplary family with one child. City streets were replete with slogans which declared that having an only child is better for the family. Children in big cities, where this policy was carried out most successfully, were dressed in good clothes and surrounded by attention and care. Families with one child also received benefits, such as the right to priority housing, free maintenance for a child in a kindergarten, advantages in admission to universities, and more.

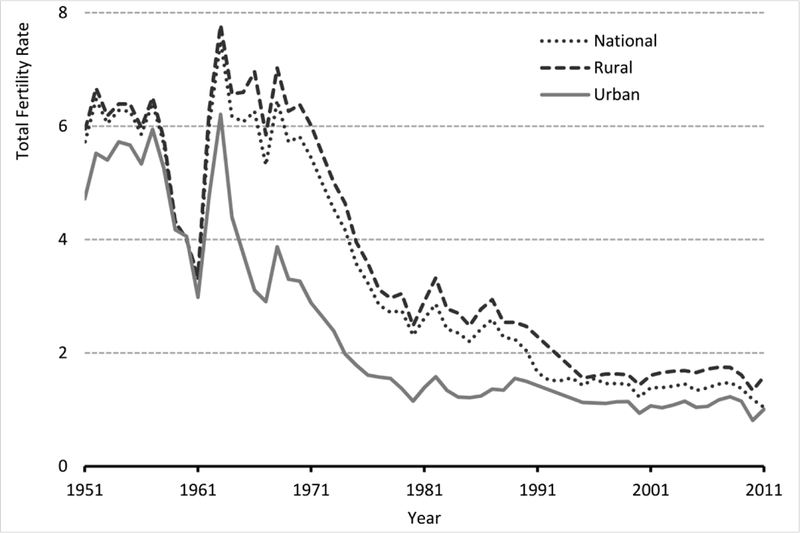

Families in rural areas with one child were allowed to increase the size of the allocated household land. For parents with two or more children, a number of different restrictions were implemented in a number of areas. For example, after the birth of a second child, parents were required to return the bonus that was paid to them monthly as a family with one child. In addition, they were forced to pay a fine, the amount of which depended on income and residences ranged from a few hundred to several thousand Yuan. The following figure how the fertility rate changed during those years.

Among the unusual family planning measures was the promotion of late marriage. Officially, the age of marriage for women was 20 years, for men it was 22 years. However, additional restrictions were introduced by the government; for example, it was strictly forbidden to create a family for students up to the threat of expelling from the institute. Nevertheless, in matters of marriage, China has gradually become an increasingly modern country. For thousands of years marriages in China were concluded by agreement between parents. Divorces ceased to be a rarity, but their share was significantly lower than in Western countries since divorce is considered a shame for the Chinese people. It should also be noted that the slogan “One family – one child” was carried out the country while taking into account local conditions and national characteristics. Thus, in areas inhabited by national minorities, the number of children could not be limited.

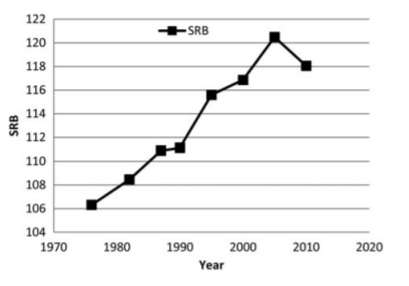

Family

Nevertheless, this policy has a number of negative consequences regarding family matters. The imbalance in the sex ratio forms is one of those negative social phenomena. The following graph demonstrates how the balance between the male and female population significantly increased due to this rule. The reason for such disparity is that it was more convenient to have a male child, rather than to have a female child. Such belief was particularly popular due to sexism in the Chinese community. Parents were convinced that a son is more likely to take care of them when they will grow old, while a daughter will be taking care of her own family. For this reason, most of female fetuses were aborted, which lead to an imbalanced sex ratio.

The reason for this is that such disparity contributes to the growth of the illegal market for sexual services, women and children trafficking, and the spread of AIDS. This demographic imbalance seriously damages the psychological health of young men, condemns them to search for brides in neighboring states (). Moreover, it generates a number of different mental problems connected with insecurity, stress, and suicidal moods, which can also lead to an increase in sexual crimes.

In Chinese society, a large number of single young men who came from families as an only child has formed a group that, for objective reasons, has limited opportunities to satisfy their need for a family. In addition, they also cannot satisfy the basic needs of the individual for love and belonging. The inability to satisfy these needs, as a rule, leads to maladjustment, aggressiveness, and unpredictability of social behavior. All of these trends create conditions for social destabilization and pose a certain threat to social security.

Furthermore, this policy also created changes in financial condition of families. On the one hand, it became easier for families to support their children. According to researchers, “singleton children received more financial investment in their education than their non-singleton counterparts; and parents spent less time supervising girls’ academic work in the presence of male siblings” (Hu & Shi, 2020, p. 381). However, under current conditions, every single child in a Chinese family is still forced to support their parents and two pairs of paternal and maternal grandparents. This is objectively an extraordinary burden for an individual who builds their own life and marriage in difficult economic conditions.

This also creates an apparent problem because for one adult, it would be difficult to support not only his own wife and children, but both parents as well. From this issue, a need for changes in policies regarding government support arises. The legislative consolidation of the obligations of adult children to their parents testifies to the urgency of the problems of financial help, as well as psychological support for elderly citizens. The disregard of this problem can lead to the increase of disrespectful and cruel treatment of elderly relatives.

Economy

In less than 40 years, as a result of effective birth control in China, an accelerated demographic transition from the traditional model of population reproduction took place. From high fertility and mortality rates, it was changed to a modern model characterized by low fertility and mortality, low population growth. In addition, the changes occurred regarding the structure of the population in favor of older age groups and a gradual reduction in the share of the working-age population.

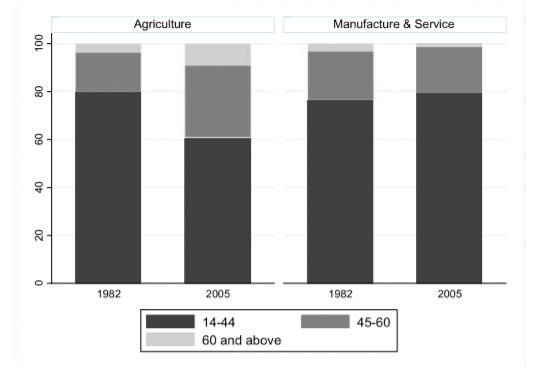

At first, the birth control policy and the resulting drop in the demographic burden have contributed greatly to China’s rapid economic growth. There are a number of reasons for these positive changes, however, they were short-lived. The labor market was filled with young women who were no longer busy giving birth and raising children. The maintenance of a single-child family required less funds than a family with many children. Therefore, the requirements for higher wages were not aggravated, and labor remained cheap. The state freed itself from the obligation to take care of the education and employment of the second and subsequent children. As a result, it became possible to increase the share of savings and investment. In the early 2010s, the demographic burden reached its minimum, and the growth in the proportion of the elderly in China’s population

has already begun. The following figure demonstrates how labor forces were distributed among the population.

The previous graph demonstrates how the working age was transformed due to the one-child policy. This result was produced by the researchers’ own calculation “based on the 1982 Population Census and mini-census in 2005 of China” (Wang et al., 2017, p. 52). From this outcome, one can see that a significant amount of old people works in agriculture in recent years. Wang (2017) also indicated that “labor markets may encounter a shortage in the labor force if the industrial structure fails to transform properly” (p. 64). In addition to this alarming trend, there is also a steady increase in the population of people over 60 years old.

There is no doubt that this increase is also becoming a problem for the government for several reasons. The rapidly aging society expects from the state the creation of specialized services focused on the specific needs of this age group. In addition, the elderly also need the development and implementation of new technologies of social support. Researchers note that the “significantly accelerated the advent of an aging society, radically altered the structure of the population, and made eldercare a more challenging task” (Nie, 2016, p. 364). Aging also affects the standard of living of older people, which leads to an increase in the number of the poor.

The sharp decline in living standards after 60 is associated with a drop in income due to retirement status. As was stated above, one-child policy also restricts the opportunities for the elderly to get support by their children. As researchers state, “such policy exogenously reduces the availability of talented heirs, which in turn greatly lowers within-family successions and results in discontinuity of family firms since most family firms rely on within-family succession” (Cao et al., 2015, p. 328). Speaking about solving the problem of population aging in China, it should be emphasized that a significant part of the research and discussion on this issue is focused on the material aspects faced by older people. It includes the level and equity of retirement allowance, the cost and availability of medical and nursing services, financial support that should be provided to them by the state, and adult children. Much less attention is paid to the low quality of their life, the problem of emotional and social assistance faced by representatives of older age groups.

Possible Solutions

The problem of providing a high-quality, prosperous living conditions for the older age groups must be addressed in a comprehensive manner. The government has already rejected the one-child policy; however, its consequences will still be present for several decades. Therefore, China’s traditional family care system for the elderly should eventually be replaced by social insurance for old age, as well as family care and community-based, charitable, and commercial services. The creation of such an innovative model is in the interests of both the population and the state. The reason for this is that it meets the needs of older people and contributes to the preservation of social stability and the creation of a harmonious society.

Conclusion

Due to the decision to implement a one-child policy, there is still a number of negative trends in the structure of China’s population. For this reason, changes in this rule policy is considered to be timely and vital. As a result of the implementation of new attitudes in family planning in the long term, the size of the working-age population will stabilize, and the aging rate will slow down. Moreover, the age and sex structure of the Chinese population will also improve and be more equal. The adjustment of family planning policy will certainly play a positive role in putting the Chinese economy towards more productive development. It will also create objective grounds for reducing its traditionally high savings rate and stimulating the growth of markets for goods and services. All these interventions will have a positive impact on the Chinese economy and give a new impulse to its growth in the long term.

The Chinese experience of family planning and solving the problem of aging of the population is an important contribution to the research about the demographic situation in the world. For this reason, it is of particular interest for the leaders of developing countries, where the problem of improving the quality of life of older people does not lose its relevance. The socio-economic development of such a populated country as China can give rise to new problems and contradictions that are difficult to predict at this stage. That is why the demographic situation and the acute social problems associated with it, the successes and failures of the Chinese leadership require constant monitoring and a scientific analysis.

References

Cao, J., Cumming, D., & Wang, X. (2015). One-child policy and family firms in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 33, 317-329.

Hu, Y., & Shi, X. (2020). The impact of China’s one-child policy on intergenerational and gender relations. Contemporary Social Science, 15(3), 360-377.

Loh, C., & Remick, E. J. (2015). China’s skewed sex ratio and the one-child policy. The China Quarterly, 222, 295-319.

Nie, J. B. (2016). Erosion of eldercare in China: A socio-ethical inquiry in aging, elderly suicide and the government’s responsibilities in the context of the one-child policy. Ageing International, 41(4), 350-365.

Wang, F., Zhao, L., & Zhao, Z. (2017). China’s family planning policies and their labor market consequences. Journal of Population Economics, 30(1), 31-68.

Whyte, M. K., Feng, W., & Cai, Y. (2015). Challenging myths about China’s one-child policy. The China Journal, (74), 144-159.