Executive Summary

This study presents a market exploration structure known as the PESTEL analysis model. At the back of the continued pace of aviation technology, drones have become important tools in almost every industry. The study examines various PESTEL factors with a view of seeking the best strategic marketing plan for establishing a drone business in Italy, which is deemed to have an auspicious social, political, and economic environment that will favour the selling such products. Like in other G8 countries such the US and Germany, UAV regulations in Italy are being changed to allow the use of drones for commercial purposes. However, the biggest business opportunity in Italy lies within filming, monitoring, and aerial surveillance industries. These sectors present a viable market for the drones. The business will serve the Italian market in a variety of ways.

For instance, the robots will be used to monitor wild animals, put off wildfires, deliver quick foods (such as pizza), transport medicine, and assist journalists to take photos and videos among others. The need of drones in Italy has been underpinned by the fast growing economy and stable political climate with a government that supports remotely piloted aviation systems (RPAS). Since the drones are designed to perform unique tasks, the company will provide diversified products to tap the market opportunity. The drone market in Italy is growing very fast; hence, the potential for selling drones is huge. For instance, about 3% the monitored sales points offered for this market in January 2015 revealed an exponential growth to about 18% at the end of that year. Some sources also indicate that over 100,000 drones were sold in Italy that year. The marketing strategy will involve targeting the Italian market niche and branding the business in a bid to stay ahead of rivals. To remain successful in the drone industry, it will be important for the company to capitalize on a powerful unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) portfolio.

PESTEL Analysis

Introduction

In the wake of new-fangled aviation technologies, the capacity to embrace innovations in both domestic and global markets has become an important subject amongst many firms. The impact of these innovations on the market is met with varying reactions based on the political, environmental, social, technological, and legal (PESTEL) factors that prevail within the targeted country. These elements have a dramatic effect on the marketing of drone technology. While the use of automatons presents many opportunities for both the government and its citizens, it comes with associated risks such as threat to privacy and misuse by criminals. However, the technology’s advantages outweigh its disadvantages in a number of ways that will allow its use in many countries. This report explores the applicability of drone technology in Italy by examining the PESTEL factors that help in determining the state and scope of the target market.

Theoretical and Conceptual Perspective of PESTEL

Theoretical concepts form frameworks for understanding the application of various features in real-life situations. Because of the continued advancement in technology, the consumers of various goods and services have been exposed to a wide variety of unique products and services (Ziout et al., 2014). Many organisations and entrepreneurs have been making use of this opportunity. The drone is one of the most unique products that have been driven by today’s fast-paced technology. Drones are designed to do jobs that are regarded dangerous for humans (Ziout et al., 2014; Pätzold, 2017). PESTEL analysis can be used to develop a quality marketing plan for drones in Italy.

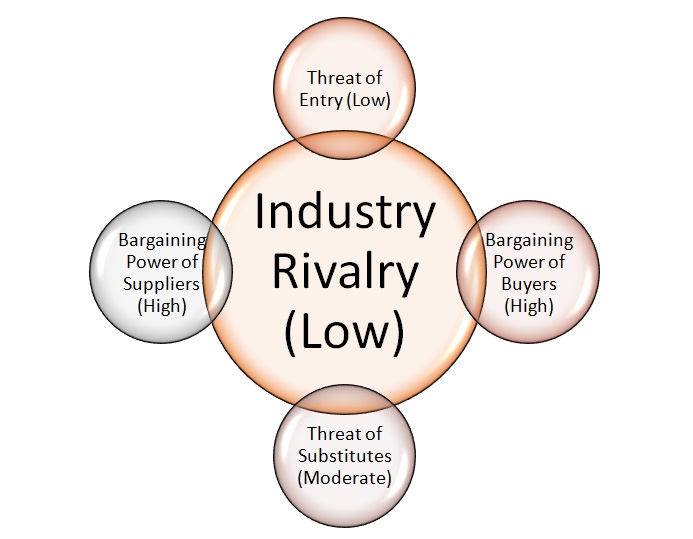

PESTEL analysis is a toolkit that is used by marketers to analyse and monitor the external environmental factors that have an impact on an organisation. It identifies various political, economic, technological, legal, and ecological factors that influence the viability of businesses (Sandvik, 2016). The application of this model enables managers to assess the risks that the identified factors pose to organisational development. The resulting knowledge plays a significant role in the formulation of informed decisions. Even though the theoretical design and nature of PESTEL require an integrated approach to analysis, the mechanical framework for the model does not sufficiently support such a method (Ziout et al., 2014; Shalal, 2015). However, Porter’s five competitive forces that shape strategy can fill the gap. Thus, it will be important to take into consideration the threats of new entrants, bargaining power of the suppliers, bargaining power of buyers, threats of substitute products or services, and rivalry among existing competitors.

Porter’s Five Forces

Pätzold (2017) reveals companies that have ventured into the industry are still few. Thus, the company will enjoy an environment with minimal competition as other international firms gradually venture into the business. Since there are a few players currently, the competitive rivalry is expected to be low. The company will offer drones designed for unique jobs; thus, the bargaining power of suppliers will be high while that of the buyers will be low (Shalal, 2015). This situation will create a haven for generating profits as the company enjoys market domination. Lastly, Pätzold (2017) attests that there are moderate substitute products for the drones that have been introduced in the Italian market. Therefore, it can execute a supple marketing strategy by selling unique automatons to gain a competitive advantage over the competitors.

Porter’s Five Forces in the Italian Drone Market

Italy is one of the G8 countries that offer a plethora of avenues in which the drone technology can be used. The analysis of the PESTEL factors will enable the company to understand the nature, suitability, and readiness of the Italian market for the drone technology (Lee and Choi, 2016; Keller et al., 2017). It will also provide data and information necessary for predicting the possible challenges that will come along with the adoption of this technology in the near future (Lee and Choi, 2016; Tong, 2017).

Examining PESTEL Factors

Economic Factors

Shalal (2015) reveals that Italy is one of the G8 countries that have realised a significant economic growth and increase in the amount of disposable income in the last decade. This state of affairs has raised a need to support various operations using UAV technologies (Rae, 2014).

For instance, the transport sector, which is central to the economy of Italy, calls for constant monitoring of automobiles to manage traffic congestion. In such a situation, the traffic police department will need drones to control the movement of vehicles efficiently (Custers, 2016). Through this plan, they will be in a position to respond swiftly when accidents occur on the roads.

The agricultural sector will benefit a lot from the drone technology. The expansive wheat farms need drones for monitoring and spraying pesticides (Barrett et al., 2015). Although the government has neglected the agricultural sector, it is evident that Italy has one of the world’s best climates when it comes to the food production. The country’s economy can be improved significantly by focusing on modern farming practices (Custers, 2016). Therefore, the drone company will sell in Italy as the farming industry will also be instrumental in providing security to the farms especially in spotting arsonists who intend to destroy the plantations (Barrett et al., 2015). The drones have cameras that can show images at night.

Besides, the film industry incurs a lot of expenses when shooting aerial films especially when they have to use helicopters. Drones are cheaper; therefore, the Italian business community in the film production industry will readily embrace the drone technology as it will help to cut down their cost of production. Sovacool et al. (2015) reveals that Italy is a lovely place and professional photographers and filmmakers will enjoy taking pictures and videos from the sky provided they abide by the Italy drone laws. The drone technology is good news for this Italian tourism industry. For instance, drones can be used to locate poachers and wild animals in trouble (Kuzma et al., 2017). The robots can also be used to film the tourist attraction sites such as the beautiful horizons of Italy, the mountains, and other sceneries (Nord et al., 2017; Alvarez and Marin, 2013). This will go a long way contributing to the growth of their economy.

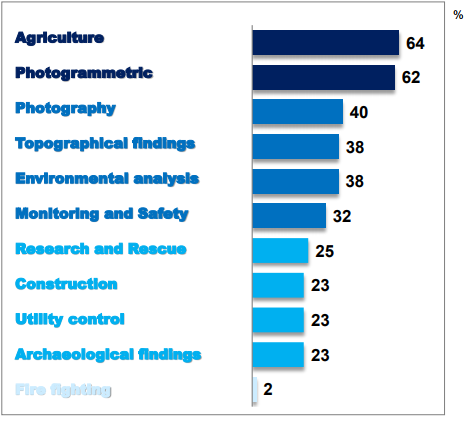

The graph below shows the areas of greatest development for the use of drones in Italy (Doxa Marketing Advice, 2015).

Political Factors

According to Barrett et al. (2015), the Italian government is politically stable. This provides a peaceful environment for investment as the investors are not at a risk of losing their business assets to attacks and destruction (Smith, 2015; Custers, 2016). The country’s enduring political environment favours the marketing of drones. Like in other G8 countries, the Italian government is now changing regulations to embrace commercialisation of drones. This situation will support the market to the company since most people wish to buy robots for large-scale business operations (Smith, 2015; Da Silva Andrade et al., 2015). Small business operators can also use the drones to ensure that their businesses are run properly.

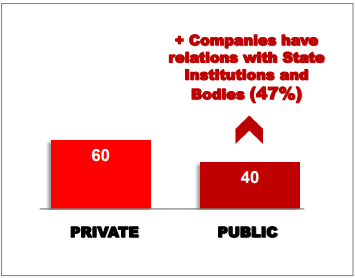

The Italy drone law allows foreign financiers to invest in Italy. The government encourages this practice to prevent the monopoly users of their market and to ensure that goods and services are offered to the people at affordable prices (Smith, 2015). For this reason, the private companies have tapped about 60% of the UAV market in Italy, while the public sector only serves 40% (Smith, 2015). This is a great opportunity for the establishment of a company with unique marketing strategies for drones.

The graph below shows the sector with the greatest potential for the use of drones (Doxa Marketing Advice, 2015).

Since the Italian government does not impose any foreign investors in the country, it would be a big opportunity to build a drone company in Italy (Sohel et al., 2014; Bartsch et al., 2016).

Socio-Cultural Factors

Family is one of the most valued institutions in the Italian culture. Important religious institutions, leaders, and even parents support family solidarity. Thus, the middle class is expected to raise some interest in the drone technology especially for covering special events such as wedding and burial celebrations (Straubhaar et al., 2013).

Some places in the country, especially Northern Italy, are densely populated. Although there are well-educated people who will provide adequate labour to the drone industry at an affordable cost, the dense population will pose uncertainty to the use of drones since these automatons cannot take off if there are 50 people at a range of 50 meters (Nord et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the economic needs and status of the country make it a suitable area to establish the drone business empire (Nord et al., 2017). Therefore, the country has a favourable business climate for drones since they can be applied to its various sectors.

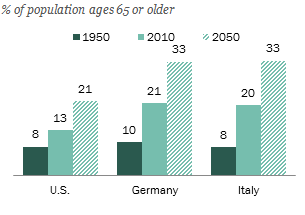

Besides, Italy population exhibits a demographic seesaw with an elderly cohort; hence, there are a few young people who are expected to be adventurous and love the fun of experiencing new technology (Nord et al., 2017). The cultural taste of the young generation lacks in the Italian drone market. This situation creates a big challenge for the drone company since the company targets people aged between 25 and 50 years (Ewers et al., 2017; Engelman et al., 2015). From the graph below, it is clear that Italy is one of the countries whose elderly cohort is high.

The graph below shows a comparison of the growing population of old people in the US, Germany, and Italy (Doxa Marketing Advice, 2015).

Limitations of PESTLE Analysis

The most notable aspect of PESTLE analysis is that it does not involve a quantitative approach to measurement. As a result, it fails to give clear information about the qualitative aspects of the target market (Ramadan et al., 2017; Barrett et al., 2015). In place of this, Porters five forces that shape industry competition can be used. However, this underpinning cannot point out various uncertainties that may hinder the success of business establishment in Italy (Canadian Trade Commissioner Service, 2015). The use of this method in analysing the market leaves out the determination of other elements in the external environment.

The theoretical element of PESTLE analysis adopts an all-inclusive method despite the fact that it is not shown in the measurement and costing dimension. These factors analysed are measured and evaluated independently (Alon et al., 2016; Kapogiannis et al., 2015). On the other hand, considering the effect degree, aspects in the peripherals do not have similar effects on the business activities. While some of these factors have considerable or critical effects on the company’s operations, others only have a limited effect.

The factors in PESTLE analysis may differ in their relative importance. Thus, there is also a need to adopt a technique that allows for measurements of the importance of various factors and subfactors of the macro-environment of the company in question (Alon et al., 2016). It is important to consider in a holistic perspective the relationship and interactions between the PESTEL factors. Independent measurements and evaluation of the elements separately may not reflect the actual situation.

Recommendation

From the PESTEL analysis above, it can be recommended that the company should start marketing and selling drones in Italy. The country has proven to provide an amicable climate that can enable the business to do well and reap huge profits (Canadian Trade Commissioner Service, 2015). Besides, under the new drone regulations, Italy has allowed commercial use of drones which is presents a big opportunity for the company.

Conclusion

PESTEL analysis provides a significant approach to the identification of strategic markets for unusual goods and services. With better knowledge of the market, one knows the merits and demerits of a business. The idea of establishing a drone industry in Italy will definitely be excellent as there is a ready market provided by the stable political environment, favourable government policies, and a modern culture that appreciates the drone technology. Besides, the introduction of the robots in the country will be underpinned by the stable tourism and filmmaking industries. The success of any business is directly related to the satisfaction of the target customers. Since the Italian people understand the importance of the introduction and implementation of drone technology in their country, they will readily buy the idea.

Reference List

Alon, I., Jaffe, E., Prange, C. and Vianelli, D. (2016) Global marketing: contemporary theory, practice, and cases. London: Routledge.

Alvarez, I., and Marin, R. (2013) FDI and technology as levering factors of competitiveness in developing countries. Journal of International Management, 19(3), pp.232-246.

Barrett, C., Landowski, R., Sheng, J. and Baiocchi, O. (2015) Drone-based wireless network sensors for forest fire detection. XV Safety, Health and Environment World Congress. Web.

Bartsch, R. I., Coyne, J. and Gray, K. (2016) Drones in society: exploring the strange new world of unmanned aircraft. London: Taylor & Francis.

Canadian Trade Commissioner Service. (2015) Unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) market sector profile 1 Rome, Italy [online]. Web.

Custers, B. (2016) Future of drone use. The Hague, Netherlands: TMC Asser Press.

da Silva Andrade, C., Peter, L., Will, M., Breda Mascarenhas, L. A., Campos da Silva, R. and de Oliveira Gomes, J. (2015) Evaluation of technological trends and demands of the manufacturing industry to a center of R & D & I. Journal of Technology Management and Innovation, 10(3), pp.104-119.

Doxa Marketing Advice. (2015) Survey on the Italian drone industry: profile of sector companies, Doxa Marketing Advice. Web.

Engelman, R. A. Q. U. E. L., Fracasso, S. and Schmidt, S. (2015) The influence of intellectual capital on absorptive capacity and product innovation. Web.

Ewers, E.C., Fish, L., Horowitz, M.C., Sander, A. and Scharre, P. (2017) Drone proliferation. Web.

Kapogiannis, G., Gaterell, M. and Oulasoglou, E. (2015) Identifying uncertainties toward sustainable projects. Procedia Engineering, 118(1), pp.1077-1085.

Keller, F. H., Daronco, E. L. and Cortimiglia, M. (2017) Strategic tools and business modeling in an information technology firm. Brazilian Journal of Operations and Production Management, 14(3), pp.304-317.

Kuzma, J., O’Sullivan, S., Philippe, T. W., Koehler, J. W. and Coronel, R. S. (2017) Commercialisation strategy in managing online presence in the unmanned aerial vehicle industry. International Journal of Business Strategy, 17(1), pp.59-68.

Lee, S. and Choi, Y. (2016) Reviews of unmanned aerial vehicle (drone) technology trends and its applications in the mining industry. Geosystem Engineering, 19(4), pp.197-204.

Nord, J. H., Riggio, M. T. and Paliszkiewicz, J. (2017) Social and economic development through information and communications technologies: Italy. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 57(3), pp.278-285.

Pätzold, M. (2017) Fifth-generation technology offers trillion-dollar business opportunities [mobile radio]. IEEE Vehicular Technology Magazine, 12(3), pp.4-11.

Rae, J. D. (2014) Analyzing the drone debates: targeted killings, remote warfare, and military technology. New York, NY: Springer.

Ramadan, Z. B., Farah, M. F. and Mrad, M. (2017) An adapted TPB approach to consumers’ acceptance of service-delivery drones. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 29(7), pp.817-828.

Sandvik, K. B. (2016) The political and moral economies of dual technology transfers: arming police drones. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Springer International Publishing.

Shalal, A. (2015) U.S. government approves Italy’s request to arm its drones. Reuters. Web.

Smith, K. (2015) Drone technology: benefits, risks, and legal considerations. Seattle Journal of Environmental Law, 5(1), pp.291-302.

Sohel, S. M., Rahman, A. M. A. and Uddin, M. A. (2014) Competitive profile matrix (CPM) as a competitors’ analysis tool: a theoretical perspective. International Journal of Human Potential Development, 3(1), pp.40-47.

Sovacool, B. K., Linnér, B. O. and Goodsite, M. E. (2015) The political economy of climate adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 5(7), pp.616-618.

Straubhaar, J., LaRose, R. and Davenport, L. (2013) Media now: understanding media, culture, and technology. Boston, Massachusetts: Cengage Learning.

Tong, J. (2017) Digital technology and journalism: an international comparative perspective. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ziout, A., Azab, A. and Atwan, M. (2014) A holistic approach for decision on selection of end-of-life products recovery options. Journal of Cleaner Production, 65(1), pp.497-516.