Executive Summary

In a modern globalised environment, businesses encounter a variety of cultures which can create challenges for their operations. Cultural competency and ethical leadership serve as critical elements for the growth and success of a company. This report examines a case study from a perspective of culture, particularly its impact on strategic, ethical decision-making in business engagement. The role of leadership is also examined and combined to evaluate a hypothetical decision from an ethical perspective. The globalised nature of a business is discussed and applied to the concept of expanding into China, observing how staffing and management will be impacted from a cultural standpoint in multinational enterprises.

Introduction

Cultural competency and its impact on client interaction and ethical, strategic decision-making is a vital aspect of the modern globalised business environment. The conceptualisation of business ethics and practices within varying cultural influences is driven by numerous theoretical models and applications of social responsibility. However, cultural factors may be potentially detrimental to the success of a company, as demonstrated by the case study examined in this report. Ethical decision-making consists of two major theories of teleological and deontological choices. The company in the case study is inherently influenced by a variety of cultural dimensions when engaging in business which poses an ethical dilemma to its strategic decision-making, leading to the necessity of changing its process and improving cultural competency to maintain a competitive advantage in a globalised environment.

Impact of Culture

Business ethics are heavily defined by culture, both internal and external. In some companies, employees, including high-level executives, state that corporate values directly conflict with personal morals. This suggests that the demands and actions made by leadership are inherently unethical. The immorality conflicts with the personal values of individuals, which are deeply integrated and broad values of their respective cultures. There is an underlying belief that business is competitive to the point of cut-throat actions that disregard most ethical norms (Solomon 1993). However, in reality, any given industry depends on the stability and foundation of shared interest and mutual agreement of conduct.

These rules contribute to the concept of corporate culture, a social virtue that rejects individualism and instead recognises employees as part of a business structure. The jobs that people hold are more than a play of employment; it is a moral dimension based on the work done, cooperation with colleagues and concerns for the company and community. This forms the corporate culture, which embraces ethics and highlights the importance of shared values to maintain a culture (Solomon 1993). Meanwhile, business is a context that is deeply embedded and supported by society with whom it must also share cultural values and expectations in order to thrive.

A contingency approach is popular in management theory, emphasising that there is no one ethically best method or universal answer, but rather the behaviour and solutions will differ based on circumstances. Everything ranging from organisational structure and internal culture to strategic decision-making and leadership styles is contingent upon the environment and circumstance. Therefore, in application to business ethics, it can be argued that all societies and cultures need a system of ethical standards that, with some level of effectiveness, can create an environment and circumstances for safe business transactions. The ethical values are meant to encourage trust, which is paramount for individuals and companies to cooperate and have the protection that if trust is broken, sanctions would be applied. As insurance against untrustworthy practices, contracts are inherently used to ensure the enforcement of the sets of values, making it in the mutual self-interest of parties to demonstrate trust (Fisher, Lovell & Valero-Silva 2013). These safeguards may also differ based on culture, such as a threat of a lawsuit in the West or family networks in the East, both of which cement business relationships. However, the outcome always remains the same, which is to establish a set of moral standards contingent on suitable circumstances that can guide strategic, ethical decision-making.

Nationality and other cultural-related factors impact contexts that influence strategic decision-making. The can include economic conditions, the presence of competition, local and national regulations, the availability of labour supply and purchasing demand and the nature of the business. One way or another, culture influences these aspects. This is why it is important to recognise that inherently similar industries implemented in different countries will face radically different conditions and subsequent outcomes. A good example of such is utilities, as countries differ in how they approach this industry. While some regions have government-run monopolies, others have a combination of regional monopolies and private firms. Thus, this identifies the level of regulation, level of competition and the functioning of the economic system (Dorfman & House 2004). Considering these factors, it can be argued that the role of culture, influenced by local contexts, will undoubtedly impact ethical, strategic decision-making. Although the examples mentioned are on a higher national level, this extends down to the local level of interaction with consumers and policies which companies adopt in order to uphold the cultural business ethics while remaining competitive.

Various countries and cultures will have different ethical standards interconnected with religious, philosophical and historical traditions. In turn, teach region will vary in ideas on how to conduct business practices and structure organisations. Some places see profitability and expansion as the primary goal, while in others, it is a supplemental goal. It is possible to have competing values regarding business and management, particularly if a culture is undergoing change and modernisation. However, according to the essentialism approach, societies usually have distinct ethical values that are shared by the general population, and these standards remain stable and internally consistent over long periods. Essentialists also believe that some ethical norms transcend national and cultural boundaries as a result of consciousness or commonality of human nature (Fisher, Lovell & Valero-Silva 2013).

The difference in ethical standards in various countries creates difficulty in both pragmatic and philosophical approach to business ethics. Attempts to define customary values are undermined, leading to the common maxim “when in Rome, do as the Romans do” when approaching business behaviour in other regions or towards other cultures. However, this presents an ethical challenge in itself since a company may not agree with the practices or values of another culture, either having the choice to leave or adopt a relativist approach to accept any standards as long as it is part of the tradition.

Appraising Ethical Leadership

Leadership culture is a sequence of purposes, critical behaviours and personal values which have been identified by leaders as viable to the organisational culture and is demonstrated by leader role models in daily communications and actions. An effective leader should be able to understand and adjust behaviour based on the context of the situation, considering values, beliefs and leadership style when making the choices. Leadership culture is inherently the consistent and authentic display of this behaviour, with the primary source of authenticity coming from personal ethical values. Forming a leadership culture is a continuous process where leaders create, manage and communicate through the integration of ethos, focusing particularly on collective identity. As a result, the social influence of leaders should produce results since their values are directly linked to the origin of their journey (Aitken 2007). Therefore, they hold an understanding of how behaviour change influences organisational culture through particular mechanisms.

The impact of culture on leadership approaches should be considered. American leaders, for example, demonstrate forward-thinking spirit and assertiveness, attempting to reach achievement at all cost. UK leadership is more based on its feudal past, with the presence of a class system and the management style tends to follow strict pragmatism and intent for profitability. Cultural influence on leadership to some extent impacts the importance and perception of ethics, as well as what those moral standards are. In some cultures, it is acceptable and almost expected to engage in rule-breaking and even corruption, while others value control and regulation (Lewis 2006). In general, it can be considered that Mike displays ethical culturally-appropriate leadership by demonstrating Western entrepreneurial spirit while showing honesty and respect for customers, even if they are from other cultures. His business engagement tactics are based on openness and understanding, emphasising tolerance and connection across cultures.

Research in leadership theory and behavioural tradition found that there are consistencies and differences among cultures regarding leadership behaviours. Although most studies have been ethnocentric, those that have been comparative found that there are certain universal leadership elements that are desired across all cultures, while others are more dependent on the nation of origin. It was found that leader supportiveness, contingent reward and charisma were prototypes demanded in practically every culture. Meanwhile, aspects such as participation, directiveness and contingent punishment vary strongly depending on culture (Dorfman & House 2004). Since national identity and type of industry are vital aspects of the environments where companies function, leadership styles and ethics are by implication also under the influence of the culture in which they operate. Influential factors which create the stimulating environments for strategic, ethical decision-making are idiosyncratic and have unique effects on various leaders depending on the context and ethical dilemmas they may face.

A study of nine enterprises from around the world that were selected for their sustainability had similarities among their leaders. They were young entrepreneurs who focused on ethical sustainability principles from the inception of the company, attempting to have positive environmental and social impacts while making a profit. This is a type of value-based business that ends up successful and transforms both the industry and society because of the virtue and moral behaviour of the leaders. Therefore, the sustainability and virtuous approaches of these companies are directly anchored in ethical leadership. Transformational leaders and social entrepreneurs are unique due to the moral influence they hold over employees, organisations and the community (Wang, Cheney & Roper 2015). Analysing Mike in comparison to such entrepreneurs, he fits similar moral character and virtue characteristics. He demonstrates a character of social responsibility and customer orientation. Mike takes a competent and balanced approach to decision-making, not focused on pure profitability but on building a sustainable model for his business.

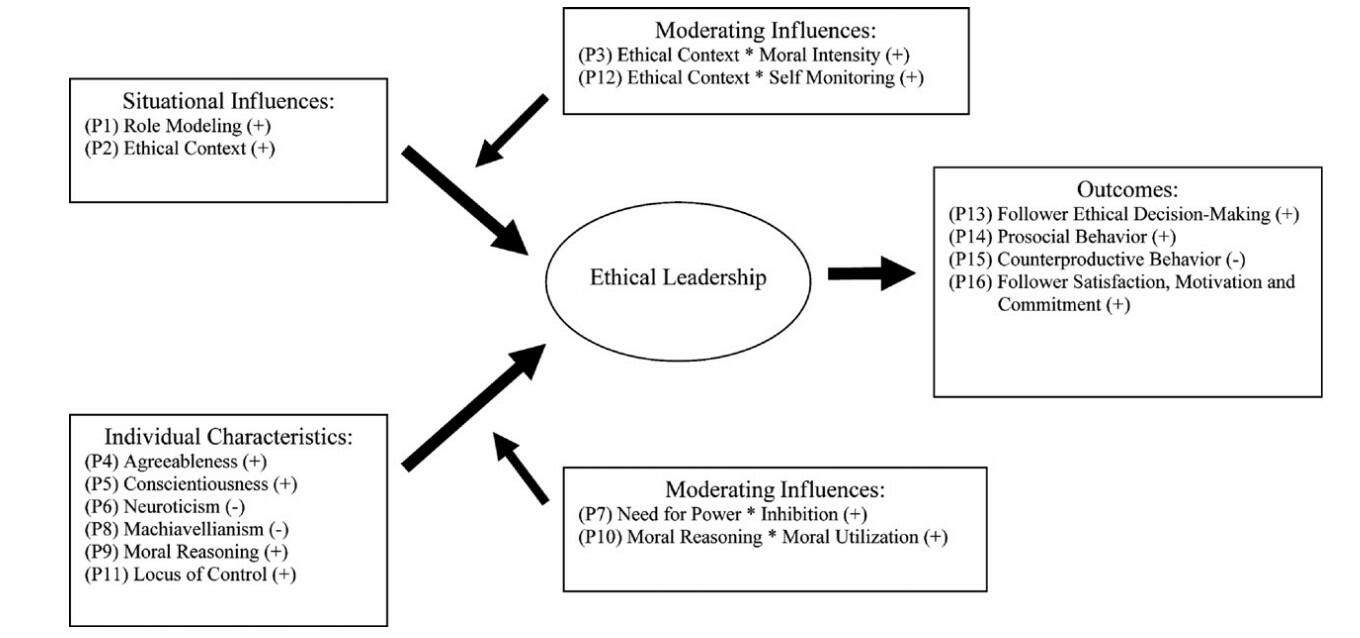

Examining Mike from an ethical leadership perspective, he demonstrates many characteristics and aspects of moral behaviour, both as a manager and an individual, which can be considered ethical. Individual characteristics of agreeableness, conscientiousness, moral reasoning and a locus of control are shown in combination with situational factors such as role modelling and ethical context. Through external influences, there is evidence of a moral code and its utilisation along with self-monitoring and inhibition (Brown & Treviño 2006). In Figure 1, it can be seen that these characteristics are vital to ethical leadership, which are then exemplified through certain outcomes. Aspects such as followers making ethical decisions, employee satisfaction and commitment, as well as pro-social behaviour are among some of the examples. The case study demonstrates patterns of ethical leadership in changing contexts and moral dilemmas where Mike chooses to act humanely and attempt to find other culturally appropriate solutions rather than chase after profitability and personal gain.

Application

Making the decision to work with only English-speaking customers would be an incorrect and unethical decision in this case. Language is inherently a part of international business operations, an element in the sequence of decision-making and resource allocation on a day-to-day basis. Modern businesses, no matter if international or local, must navigate the numerous language boundaries (Brannen, Piekkari & Tietze 2014). The perception of English as a lingua franca poses the challenge of English hegemony.

It is unethical to adopt such a strategy, as it would be inherently discriminatory. In a setting that is dominated by English, non-native consumers are ultimately disadvantaged, creating unbalanced power dynamics as English speakers often benefit from the communicative inequality. The prejudices against non-fluent speakers labelling them as incompetent result in discriminatory and predatory practices, particularly in business. It creates a social hierarchy that often poses business owners with the question of whether to avoid non-English speakers altogether. Based on the Ecology of Language Paradigm, it is ethical to advocate the right to language, supporting an individual’s freedom to use the language of their choice. Furthermore, it advocates equality in communication as a logical and ethical approach to using linguistic localism. It is a practice of using the language based on whom one is speaking to, if possible or at least a neutral and balanced attempt at communication rather than enforcing English (Tsuda 2013). The Ecology of Language Paradigm is ethical guidance in intercultural communication that should not be violated in business practice.

Globalisation brings different cultures closer together, allowing for an examination of concepts and values, many of which may clash. This can be seen in the vital aspect of a contract which is central to the case study. While the word can be easily translated, it has various different interpretations depending on the language in the culture. For Westerners, a contract is a legal document that must be adhered to legally. The Japanese may see a contract as amendable based on circumstance, while Hispanics would view it as an ideal to strive towards in an agreement (Lewis 2006). While these cultural disagreements ultimately exist, they are not a justification for divisive behaviour. In turn, it is ethical to consider these issues and come to negotiations in a manner that is accepting and considerate of multicultural perspectives.

The core concept of ethical decision-making means to balance choices in a manner that discards bad ones and emphasises good actions. Although the typical question of ‘what would a reasonable decision be in a specific scenario?’ may be helpful, it is difficult to apply in complex situations. Three rules of management may be beneficial in resolving ethical decisions. This includes the rule of private gain, questioning whether one benefits at the expense of another, identifying personal ethics. Another rule is examining if “everyone else does it”, attempting to determine the outcomes and who would be influenced by the decision, outlining unethical behaviour. Finally, one must examine the benefits in comparison to the burdens (Chmielewski 2004).

If these rules are applied to the case study, it is evident that a decision to avoid non-English speakers would be unethical. First, it would be at the expense of many foreign clients who may find the service helpful. Also, it is not a common practice due to its discriminatory nature and may have negative legal, moral and financial consequences. Finally, the benefits of this decision are unclear and inconsistent as similar issues may arise even with English-speaking customers, and the approach may need to be focused on staff training, reforming the marketing pitch and rewriting the contract wording.

The core of modern business ethics no longer attempts to criticise business practices and portray companies as profit mongering entities. Instead, it sees corporations in the context of productivity and social responsibility, in terms of how it serves the surrounding society (Solomon 1993). Western products, services and consumer values often clash with non-materialist perspectives of Eastern cultures. Globalisation creates a unique position where populations begin to share common expectations and demands for services based on interacting values (Fisher, Lovell & Valero-Silva 2013). Therefore, in the context of a globalised environment, businesses chose to adopt a customer-oriented approach. A pragmatic, market-driven strategy was matched with normative aspects that emphasised ethical organisational procedures. Customer needs began to matter from a perspective of business ethics and strategic decision-making (Hofstede, Hofstede & Minkov 2010). In conclusion, companies hold a certain responsibility for the well-being of a community and all consumers based on a business ethics approach. Thus, it would be inherently unethical for Mike to serve only English-speaking clients and violate numerous aspects of ethical and corporate social responsibility.

Alternatives and Recommendations

The changing global business environment is rapidly diversifying, requiring consideration that a company’s own values and ethical code are the only correct way of conducting business. Both clients, co-workers and partners will have varying cultural perspectives on ethics, possibly radically different from the ones the staff is accustomed to. Cultural differentiation, even in large globalised firms, is dependent upon the intermediate roles of the local sales force, which have the responsibility of “translating” the marketing pitch to customers, many of whom are non-native speakers. Business ethics concepts vary from one culture to another, directly involving cultural values in business transactions. It is important to consider that the market for services is difficult to adapt to globalisation since services are in their nature meant to be personalised (Hofstede, Hofstede & Minkov 2010). Therefore, services cannot be easily created for some universal intercultural standards. Understanding this and aiding the organisation to understand vital differences among cultures will aid in building business relationships, ranging from partnership deals to negotiating door-to-door contracts with clients.

There are a number of steps that a business can take to ensure a high level of ethics in its practices. First, it is important to develop a clear and articulate set of core values that would be encompassed in its mission and policies. Strategic decision-making should be aligned with these culturally sensitive and competent values, as well as recognising when the moral standards may conflict in working with other cultures. While the policy is important, companies should also have a flexible approach as cultural encounters are unpredictable and may require imagination to go outside the guidelines. Companies should focus on robustness with the employee base exercising responsibility and competent professional judgment. Employees should be trained to work with cultures that they interact and make culturally sensitive strategic decisions. A flexible but strong approach should be taken to ethics training. While policy forms legal protection for the company, and organisational ethical code and cultural approach are inherently more important (Gerasimova 2016).

Economic globalisation has led to the dynamics of the business environment to divert from Anglicisation and focus on a more complex and multilingual strategy. Adapting the consumer or local cultures and language is a vital component for penetration in order to remain competitive. The assumption of a universal international language is becoming largely obsolete as businesses choose the more efficient method of penetrating local markets based on the existing languages (Ominiyi, Afolabi & Udo 2011). It is commonly known that cultural and language differences are a barrier, but despite this, it has not been a critical factor in management research. International corporations have taken on a systematic and structured approach to resolving this issue, which should be examined.

The primary solutions have focused on finding alternate communication channels in the short term by using translators and hiring bilingual or expatriate workers. In the long-term, it implies language and cultural training for employees, implementing strategies such as code-switching, non-verbal language and taking the time to comprehensively review agreements (Harzing, Köster & Magner 2011). Therefore, it is vital to enhance business communication and cultural competency as effective measures that can aid the company in meeting operational goals and develop productive business relationships. In the long run, it is not the general theories that drive sales but the nuances of the language and interpersonal communication that contribute to contact in a globalised environment.

Expansion into China

The Chinese consumer market has demonstrated exponential growth and shows tremendous potential for all industries, enticing companies to expand their operations into the country. However, for Western-oriented businesses, the transition may be difficult from the perspective of market size and diversity, the unique cultural practices and a completely different approach to regulation. These aspects should be considered for the company and leadership as it navigates cultural barriers while staffing and managing operations in the country.

Cultural Barriers

The manner that Chinese businesses operate often differs significantly. Familial loyalty is considered an ethical duty for Chinese companies based on Confucianism. They support the development of personal relationships both inside and outside the family as a manner of developing contractual trust, as mentioned earlier. Companies are secretive, maintain low public profiles and choose private networks to finance ventures and engage in business. There is a significant amount of honour- and reputation-based deals that drive strategic decision-making. To some extent, this allows more preparation and flexibility, as entities within a framework can develop preparatory emergent approaches to strategies through their channels of knowledge about the business environment. Furthermore, it allows influencing regional governments and tough regulatory agencies to secure favourable conditions and contracts. However, the ethical considerations of the Chinese are to mistrust Westerners, and it is likely they will always give priority to family and compatriots (Fisher, Lovell & Valero-Silva 2013).

Staffing

Considering the critical factor of personal networking in China in an uncertain environment, it is vital to understand the structure of firms to utilise social resources existent within their human capital. Firms can expand access to a variety of social and other resources by hiring and harnessing social capital on an individual level, allowing employees to use their networks to achieve objectives. The difficult regulatory environment and exclusion of foreigners from many local familial networks creates certain liabilities for non-native companies. International companies in China have adopted a variety of strategies, one of which is local networking, as a mechanism to mitigate barriers and liabilities. This approach is privately owned enterprises have proven to be more elastic and successful in the Chinese economy, which moving towards network capitalism more than market order and can be used to maintain a competitive advantage (Zhang & Lin 2015). The importance of this cultural nuance in China thus provides managers with an incentive to consider social contacts as a job qualification for many positions, particularly in sales and marketing, as in the case study.

However, the challenges of expanding into China by multinational corporations have led to a common practice of using expatriates in the initial stages of cross-cultural human capital management. Transferring well-trained employees into Chinese subsidiaries as managers present certain benefits such as enhanced coordination and control of business strategy across borders. There is much better communication, and expatriates can leverage technical and insider knowledge to transfer expertise and tacit knowledge to the local subsidiary. However, there are certain challenges posed as well, since this strategy is costly as local managers have to be found eventually as well. Furthermore, strategic, ethical behaviour may be affected by lack of cultural preparation and language barriers, significantly stagnating a company’s access to the market and local networking (Zhou 2015).

Therefore, it is important to consider local talent, and certain aspects should be evaluated in the process. Particularly regarding senior executives, local customs and cultural distinctions should be weighed. It should be considered that someone over the age of 40 in China will have vastly different ethical values than someone aged 30 and younger, largely due to the historical and economic transition that China underwent only in recent decades. As mentioned earlier, networking is vital to get your foot in the door, as the Chinese will most likely dismiss any inquiries made without a mutual acquaintance. Also, Chinese job titles may differ in reflecting the role and skills of an individual, with many actual executives hidden behind the scenes in Chinese bureaucracy and radically different organisational structures. Finally, decision-making capabilities depend on the strategies and ethical approach that the company plans to take off, either adapting to local customs or adopting more international practices. It is vital to consider that success in China is tied to governmental policy and relations rather than market basics (Luk 2012).

Management

An important characteristic of the Chinese workforce is the fact that cultural values such as Confucian dynamism, power distance, masculinity and the balance between collectivism and individualism, as a rule, reflect on work values. These include aspects such as self-enhancement, openness to change, contribution to society, stability and reward, as well as power and status. From a management perspective, this is beneficial, as it is encouraged to introduce Western management practices which would incorporate with local values to stimulate diligent work ethic and self-achievement while promoting the openness to change. Evidence demonstrates that after exposure to Western thought and management, Chinese nationals begin to adopt a different approach such as commercialisation and experience with industrialisation, scoring higher on associated characteristics (Jaw et al., 2007).

In order to maintain stability and enhance staff retention, it is important to build trust and mutual understanding for Chinese nationals working in multinational companies. Applying normative managerial models in China requires adjustment towards local cultural methods to be successful. It is essential to understand Chinese attitudes regarding expatriation, and in some way, the hiring of repatriates as well. Managers should recognise the role of spatial-attitudinal and temporal attitudinal prerequisites as the driving force in terms of strategic decision-making and business outcomes. Organisations should develop HR flexibility, both internal and external, as they address cultural differences (Stokes et al. 2015). The SME management approach is most effective in the context of organisational and economic change through local rather than remote methodology. A culturally informed environment and strategic partnerships aiding in transition should enhance company management and outcomes significantly.

Reference List

Aitken, P 2007, ‘”Walking the talk”: the nature and role of ‘leadership culture’ within organizational culture/s’, Journal of General Management, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 17-37. Web.

Brannen, MY, Piekkari, R & Tietze, S 2014, ‘The multifaceted role of language in international business: unpacking the forms, functions and features of a critical challenge to MNC theory and performance’, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 495-507. Web.

Brown, ME & Treviño, LK 2006,’Ethical leadership: a review and future directions’, The Leadership Quality, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 595-616. Web.

Chmielewski, C 2004, Values and culture in ethical decision making.

Dorfman, PW & House, RJ 2004, ‘Cultural influences on organizational leadership’, in RJ House, PJ Hanges, M Javidan, PW Dorfman & V Gupta (eds), Leadership and organizations, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 51-68.

Fisher, C, Lovell, A & Valero-Silva, N 2013, Business ethics and values (4th ed.), Pearson Education, Harlow, UK.

Gerasimova, K 2016, The critical role of ethics and culture in business globalization.

Harzing, AW, Köster, K & Magner, U 2011, ‘Babel in business: the language barrier and its solutions in the HQ-subsidiary relationship’, Journal of World Business, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 279–287. Web.

Hofstede, G, Hofstede, GJ & Minkov, M 2010, Cultures and organizations, McGraw Hill, New York, NY.

Jaw, B, Ling, Y, Yu-Ping, CW & Chang, W 2007, ‘The impact of culture on Chinese employees’ work values’, Personnel Review, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 128-144. Web.

Lewis, RD 2006, When cultures collide, Nicholas Brealey International, London, UK.

Luk, J 2012, ‘The ins and outs of hiring local senior executives’, China Business Review.

Ominiyi, AO, Afolabi, BS & Udo, IJ 2011, ‘Overcoming language barriers in business-to-consumer electronic service’, Computer Engineering and Intelligent Systems, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 114-128. Web.

Solomon, RC 1993, ‘Business ethics’, in MK Asante, Y Miike & J Yin (eds), The global intercultural communication reader (2nd ed), Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 445-456.

Stokes, P, Liu, Y, Smith, S, Leidner, S, Moore, N & Rowland, C 2015, ‘Managing talent across advanced and emerging economies: HR issues and challenges in a SinoGerman strategic collaboration’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 27, no. 20, pp. 2310-2338. Web.

Tsuda, Y 2013, ‘The hegemony of English and strategies for linguistic pluralism’, in P Singer (ed), A companion to ethics, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, UK, pp. 354-365.

Wang, Y, Cheney, G & Roper J 2015, ‘Virtue ethics and the practice institution schema: an ethical case of excellent business practices’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 138, no. 1, pp. 67-77. Web.

Zhang, Y & Lin, N 2015, ‘Hiring for networks: social capital and staffing practices in transitional China’, Human Resource Management, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 615-635. Web.

Zhou, Z 2015, Global staffing implementations in the Chinese MNCs.