Introduction

Since the coronavirus outbreak in March 2020, practically all regions and nations have reported cases. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 22 million COVID-19 infections and deaths by August 2020, totaling almost 800,000 (Siddiqui et al., 2020). If all governments had failed to contain the epidemic, it might have caused widespread devastation. According to Vidya and Prabheesh (2020), the global economy was expected to decline by 4% in 2020 as it faced the worst recession since World War II. Furthermore, the World Trade Organization estimated that global trade volume would fall by 12% to 35% (Vidya & Prabheesh, 2020).

The world expressed dismay over COVID-19’s risks and how it interrupted and hampered the global supply chain’s recuperation. To stop the spread of the coronavirus, nations imposed preventative measures such as obligatory confinement, travel restrictions, and the shutdown of stores and enterprises. Given the constraints, there were shortages of raw materials, labor, and food. The recent economic recession caused by the pandemic has greatly affected the global supply chain in various sectors, and therefore nations must find potential ways how to predict and prevent such a crisis in the future.

Impact of COVID-19 on the Global Supply Chain

The global supply chain plays a critical role in international development. The ability of a nation to flourish is determined by its involvement in the worldwide economy, which is primarily impacted by a country’s role in the global supply chain (Xu et al., 2020). This comprises all phases between the time raw materials are processed into completed items and the time they reach the user in other nations.

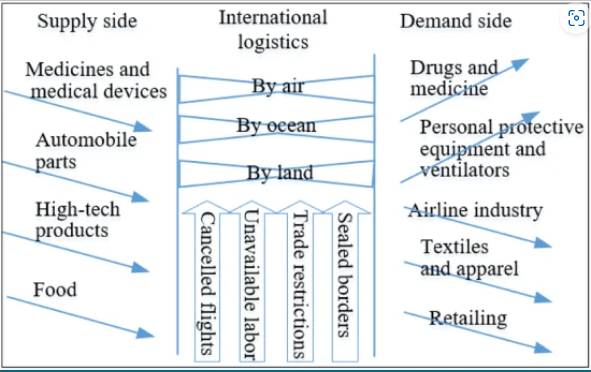

The pandemic impacted the worldwide manufacturing and distribution of goods due to travel restrictions. When COVID-19 was initially experienced in China, it caused havoc in the industrial industry. Due to its population, China is noted for being the world’s greatest consumer of major global commodities and agricultural commodities. Ports resisted massive freight while the travel limitations within and outside the nation limited the number of truck drivers needed to pick up containers from docks. Ocean carriers were no longer sailing. Manufacturing and production firms throughout the world were affected by the pandemic. Global automobile, pharmaceutical, and consumer goods merchants, among others, were hit hard. The cost of storage became unbearable due to inventory build-up. Manufacturers had to go through tedious processes to distribute their commodities.

Consequently, supply and storage containers became blocked at their ports. Container volume for ocean freight decreased by 10% thus impacting significant international importers and exporters (Xu et al., 2021). Unlike air and ocean transportation, commodities transported by land had no negative impacts. However, for nations like Italy that were heavily affected by the epidemic, the conditions for land travel grew increasingly complex. Likewise, air freight decreased due to reduced passenger flights which were required as a result of government limitations on air travel. As a result, international merchants began using cargo transportation, particularly for necessities. Due to the difficulty in getting commodities into every nation, delays in supply were caused by traffic at airports.

Potential Ways How to Predict and Prevent Possible Crises in The Future

Understanding the global supply chain’s primary vulnerabilities and monitoring potential disruptive risks in real-time is critical. Transportation and logistics, product complexity, organizational growth, financial stability and supplies, and planning networks contribute to supply chain vulnerabilities (Xu et al., 2020). Global events such as local wars, pandemics, natural catastrophes, and political disputes must be monitored by multinational corporations. This is because such occurrences disrupt the network of producers and suppliers up to the ultimate customer. Companies may improve their visibility by utilizing digital solutions and information technologies such as cloud computing, big data analytics, artificial intelligence, and 5G networks (Wang & Sarkis, 2021). By doing this, businesses may identify issues in the early stages of a complex global supply chain.

Responsive capacities enable the organization to take rapid and cost-effective remedies during a Coronavirus interruption. Capabilities upgrades deal with very sophisticated operating procedures that might obstruct sight. In the short run, inventory redundancy and alternate sourcing can help the supply chain recover quickly (Jain et al., 2020). The present inventory policy should be examined by evaluating future demand and the potential of existing providers. Furthermore, all merchandise must be removed from potentially dangerous positions. The firm must determine all alternative materials and locate local equivalents.

When considering long-term remedies, the interruption in the global supply chain is critical. These interruptions caused by COVID-19 can be addressed by planning, capacity redundancy, and supplier diversity (Mishra et al., 2021).

Firms must work effectively with all suppliers in various areas. Additional sources increase backup choices for production, supply, storage, and distribution interruptions. Applying capacity redundancy is an essential mitigating approach for organizations looking to enhance flexibility. A corporation functioning in the global supply chain with capacity redundancy guarantees that all resources, such as vehicles, gadgets, machinery, and humans, are adaptable. The resources are planned in response to new requirements, and they can increase production capacity in the case of business constraints. Due to increased capacity redundancy caused by COVID-19, the medical industry has seen emergent providers of medical items.

Effects of the Pandemic on Medical and Pharmaceutical Firms

COVID-19 had a negative impact on the pharmaceutical and medical industry’s supply chain. China produces around 42% of the world’s active medicinal components (Sharma et al., 2020). Furthermore, being the world’s third largest exporter of COVID-19 drugs, India plays a vital role in the supply of COVID-19 medications. Nonetheless, nearly 70% of Indian medicine manufacturing depends on China, and the suspension of shipments from China has resulted in significant shortages in Indian pharmaceutical enterprises (Sharma et al., 2020). Personal protection equipment (PPE) such as protective gear, respirators, medical masks, goggles, gowns, and boots are also in low supply globally, making it difficult to combat the infection. Health professionals were in significant danger of infection, and many perished in the United States, China, Italy, and Spain.

Furthermore, COVID-19 infections have caused a global demand and panic purchasing, fake news, goods hoarding, and disinformation. As a result, there have been additional shortages of crucial goods worldwide. Due to insufficient production capacity, China has been the world’s largest provider of personal protective equipment (Sharma et al., 2020). Many organizations and governments have been obliged to seek out alternative producers to assist cover the resulting shortages.

Conclusion

When the pandemic hit the world, all the key players in the global supply chain were affected. International suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, retailers, and end-user were all involved in different ways. The restrictions set by various governments made it difficult for manufacturers to process and distribute their produce. Getting raw materials from their sources took much work. Supply chain countries that relied on China for essential resources experienced shortages due to congestion at ports. Essential commodities such as medical supplies and food were in shortage. Logistics bottlenecks in the trucking industry lead to congestion at the ports.

Having visibility is essential for understanding global supply chain limits and improving manufacturing efficiency and speed. Companies may improve visibility by utilizing digital solutions and information technologies such as cloud computing, big data analytics, artificial intelligence, and 5G networks. By doing this, businesses may identify issues in the early stages of a complex global supply chain.

References

Jain, N., Girotra, K., & Netessine, S. (2022). Recovering global supply chains from sourcing interruptions: The role of sourcing strategy. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 24(2), 846-863. Web.

Mishra, R., Singh, R. K., & Subramanian, N. (2021). Impact of disruptions in agri-food supply chain due to COVID-19 pandemic: Contextualized resilience framework to achieve operational excellence. The International Journal of Logistics Management. Web.

Sharma, A., Gupta, P., & Jha, R. (2020). COVID-19: Impact on health supply chain and lessons to be learned. Journal of Health Management, 22(2), 248-261. Web.

Siddiqui, K. N., Das, M. K., & Alapan, B. (2020). Cotrimoxazole in the domiciliary management of patients with severe COVID-19: A case series. Journal of the Indian Medical Association, 34-38. Web.

Vidya, C. T., & Prabheesh, K. P. (2020). Implications of COVID-19 pandemic on the global trade networks. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 56(10), 2408-2421. Web.

Wang, Y., & Sarkis, J. (2021). Emerging digitalization technologies in freight transport and logistics: Current trends and future directions. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 148, 102291. Web.

Xu, Z., Elomri, A., Kerbache, L., & El Omri, A. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on global supply chains: Facts and perspectives. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 48(3), 153-166. Web.