Specific Aims

Due to a variety of factors, adolescent depression has become a serious area of concern for both school administrators and mental health professionals. These compelling factors have to do with, first of all, a worrying prevalence of about 5% of the teenage population (Brent & Birmaher, 2002). Gun-related violence may make the evening news and cause much breast-beating but, after canvassing 1,400 mental health professionals in public high schools, an Annenberg Public Policy Center study reports that depression and substance abuse are the most serious problems, far outranking all forms of violence (“School officials identify…” 2004). Thirdly, the adolescent life stage is typically characterized by multiple sources of such grievous conflict, stress, confusion, coping difficulties, and a recurrence rate of from 40% (two years after treatment) to as much as 70% (over a five-year span) as to provoke suicidal ideation. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that suicide is the third leading cause of death for older adolescents and the youth 15 to 24 years of age (CDC, 2005) and that in 2002, no fewer than 1,531 teenagers 15 to 19 years of age took this extreme form of coping with depression.

Given the stakes, many researchers have investigated the correlates and precipitating factors attendant to depression (see “Preliminary Studies” below). Little is understood, however, about the role of essentially unrestrained television viewing within the complex socio-demographic, family life, community, and school pressures that adolescents experience.

This research will therefore embark on a large-scale investigation of the relationship between TV exposure and self-reported symptoms. The study will rely on baseline and benchmark data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health in order to test the following hypotheses and research questions:

Accordingly, the study hypotheses should be stated as follows:

- H0, the null hypothesis: TV viewing profile does not discriminate between depressive and non-depressive adolescents.

- Ha, the alternative hypothesis: Adolescents who watch more television experience more depressive symptoms.

A combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal empirical studies should therefore address the following research objectives:

- Investigate the theory that there is a link between heavy TV viewing and adolescent depression and assess the strength of association.

- Confirm that the relationship is uni-directional, i.e., depression is an outcome of TV exposure.

- Assess gender, ethnicity, income class, level of physical activity, academic performance, and multiple TV set ownership itself as antecedents, intervening or confounding variables for irritability, anxiety, and depression.

Background and Significance

Background

Television is all-pervasive. In its many delivery formats – free-to-air, cable, pay-per-view, direct-to-home satellite broadcast, and roaming TV courtesy of cellular telephony networks – this modern medium eclipses all others in immediacy, in commanding attention, and in the spectrum of information and entertainment choices available. The advent of high-definition TV (HDTV), the continuing appeal of “home entertainment centers,” the convenience of ordering movie DVD’s, and the unending torrent of videogames all combine to make the TV set the center of home leisure time and impel family members to maximize time spent on their living room couches.

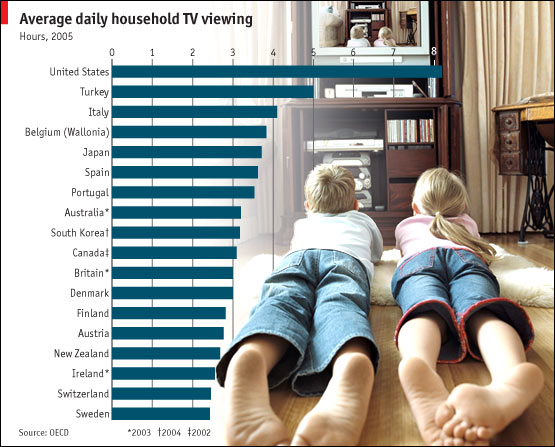

The effect of the amount of television viewed by the consumer has been a subject of controversy for many years. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (2008) reports from 2007 surveys that TV viewing absorbed no less than half of Americans’ leisure time. But at just 2.6 hours daily for the average American, respondents may have been afflicted by wanting to look good in overstating the time spent in sports, caring for children, or doing housework. Ad agencies and the TV networks themselves love to bandy about average viewing times of from 2.5 to 3.5 hours, with a view to attracting more advertiser monies. Another perspective is offered by the Economist (2007); reporting on the results of the OECD’s international “Communications Outlook 2007” review, the publisher pointed out that TV viewing increased nearly everywhere from 1997 to 2005 and that the United States was far ahead of the pack in average 8 hours and 11 minutes daily TV viewing.

Initially, media effects research focused mainly on the effects of violence in media on the propensity of children and adolescents to condone aggressive acts themselves (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963; Gerbner & Gross, 1976; Gunter, 1994). Subsequently, the field of study expanded to include other effects (described under “Preliminary Studies” below).

In the process, many psychosocial models, theories, and theories have been proposed, chiefly to explain aggression and sexual permissiveness. Those more relevant perhaps to the area of investigation are:

- Social-Learning Theory – Elaborated on by Bandura (1986) and suggesting that, among three theoretical mechanisms, vicarious experience by modeling the behavior of others explains the influential role of TV. Bandura also concluded that learned behavior is moderated by the social context in which it is observed.

- Disinhibition Theory – That television counteracts the inhibiting value of the personal experience for children and minors. Instead, sustained exposure to TV makes it more likely that the audience will accept the behavior portrayed (National Institutes of Mental Health, 1982).

- Priming Theory – The explanation posited by Berkowitz (1994) can be interpreted as suggesting that aspirational role models on television stimulate similar ideas in the short term and, in turn, awaken, make semantically related concepts more accessible. But anxiety and depression are the inevitable consequence of the fact that the portrayal, say, of a secure, the totally accomplished adolescent is hardly attainable in real life.

- Media Practice Model – At the core, this model proposes that adolescents frame their overall media mix and TV programming choice based on self- and aspired-for image. Moreover, self-image influences interaction with TV shows, and vulnerability is demonstrated by the fact that teenagers believe in media as a source of cues about important choices in life (Steele and Brown, 1995; Kaiser Family Foundation, Hoff, T., Green, L., and Davis, J., 2003).

- Third-Person Effect Hypothesis – Essentially, adolescents engage in the form of projective denial, preferring to believe that television and other media affect other persons more than themselves (Davison, 1983). Naturally, this is apt to reduce their ability to consciously cope with such influences.

- Super-Peer Theory – Being a powerful source of what is normative behavior, television effectively exercises a greater influence than the traditional teenage peer group and is all the more potent for portraying role models perceived to be both glamorous and just slightly older enough to be appealing (Mitroff, 2004).

- Cultivation Theory – Proposes that sustained TV exposure forms attitudes more consistent with the illusory situations portrayed on TV than with real-life itself (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, and Signorielli, 1994). Thus, portrayals and messages on TV impact adolescent behavior because these foster acquisition of new attitudes and behavior that may be a mirror image of what is seen on TV. Else, the influence of TV is seen in minimizing the chance of acting on previously learned responses or new cues from other sources. The mechanisms of TV-cultivated learning may involve identification with character portrayals, altering learned inhibitions, inhibiting the influence of environmental cues, or associating specific meanings with a given behavior.

Two things are clear. The first is that Cultivation Theory is an intuitively attractive model for hypothesizing a causal link between sustained TV viewing and depression. Secondly, every one of the constructs grants that sustained television exposure and the content viewed influence audiences incrementally, stimulating change in the psychological, physiologic, and behavioral functioning of often-vulnerable and predisposed viewers.

To the extent that the study validates Cultivation Theory and the multi-factor model hypothesized (under “Data Analysis” below), one may anticipate that the findings will inform intervention plans by parents, school authorities, and mental health professionals with respect to:

- Accounting for the length of TV viewing as a criterion variable for diagnosing cases of irritability, anxiety, and suspected depression.

- Investigating content viewed as these impact on self-esteem and precipitate depression.

Preliminary Studies

The Correlates and Precipitating Factors of Adolescent Depression

Intervening variables Sex may have a strong influence on the impact of consuming high amounts of television and cultivation effects. Hughes and Peterson (1980) found that the relationship between sex and television viewing was strong until controls such as hours worked per week were added. Hughes and Peterson (1980) found that women might watch more television because they were less likely to be working outside the home. Because women spent more time at home watching television, they may display higher levels of cultivation (Hughes & Peterson, 1980). Accordingly, conducting a study using adolescent males and females as subjects may be more beneficial because both sexes are spending time outside of the home.

On Television Viewing and Adolescent Depression

Researchers have proposed that the media influence people’s perceptions of reality. This research supports the view that television has a powerful effect on the viewer and the creation of his/her reality. According to the cultivation theory, television has the power to create societal norms. Prior research has shown that television portrays a society in a stereotyped and repetitive way (Cohen & Weimann, 2000). The results of the cultivation analysis may support the need for a stronger television content monitoring system.

Research Design and Methods

Research Design and Choice of Data Set

This proposal calls for a longitudinal study based on secondary research into the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (NLSAH), Waves I and II databases. The databases are accessible at the Carolina Population Center of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Carolina Population Center, n.d.). Also known as the ADD Health series, the data set was chosen specifically because it contained a measure of television consumption and depressive symptoms. Another data set that was considered was that generated by the Success and Failure in Cultural Markets study. However, the latter had no information on television usage.

The NLSAH is an ongoing study of a nationally representative sample of adolescents and young adults that started with in-school questionnaires given to adolescents in grades 7 through 12. The in-school survey was followed by three waves of in-home interviews in 1995, 1996, 2001/2002, with yet a fourth wave scheduled for either 2007 or 2008.

For the purpose of my investigation, I will be utilizing the data from Wave 1 and Wave 2, carried out from 1994 to 1996. These survey waves comprised 90,118 respondents in grades 7 through 12, of which 20,745 were followed up with in-home interviews, along with 17,670 parents. Wave 3 will not be utilized because the respondent ranged from the ages of 18-26 years of age.

The NLSAH was designed by a nationwide team of multidisciplinary investigators from the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Harris, Halpern, Smolen & Haberstick, 2006). The purpose of this study was to understand the state and antecedents of adolescent health and health behavior with an emphasis on aspects unique to adolescent life. As such, the NLSAH measured the social environments of adolescents, culling data on family, neighborhood, community, school, friendships, peer groups, and romantic relationships (Harris et al., 2006).

The Population of Interest and Sampling Frame

The public-use dataset for Waves I and II contains information on one-half of the core sample chosen at random and one-half of the oversample of African-American adolescents with a parent who has a college degree. The total number of respondents in this public-use dataset is approximately 6,500.

The NLSAH primary sampling frame was taken from the Quality Education Database (Harris et al., 2006). The database proved the most reliable way to screen for the population of interest, students. As well, the school setting provided access to the majority of respondents’ peers whose influence is fundamental to ADD Health and offshoot studies such as this one. From this frame, a stratified sample of 80 high schools was selected, filtered for those that offered the 11th grade and had a minimum enrollment of 30 students. The specific strata selected were:

- Region: Northeast, Midwest, South, West

- Urbanicity: Urban, suburban, rural

- Further stratified by school size: 125 students or fewer, 126-350, 351-775, and 776 or more.

- School Type: Public, private, parochial

- Percent White: 0, 1-66, 67-93, 94-100

- Percent Black: 0, 1-6, 7-33, 34-100

- Grade Span: K-12, 7-12, 9-12, 10-12

- Curriculum: General, vocational/technical, alternative, special education

Consequently, according to the researchers, the ADD Health sample was determined to be representative of United States schools with respect to the region of the country, urbanicity, size, type, and ethnicity.

Reliability is enhanced by the fact that, according to the original researchers, more than 70 percent of the originally sampled high schools agreed to participate in the study, and each school that declined to participate was replaced by one within the stratum. At the end of wave 1, the cooperation rate reached 80%; this improved even more to 90% in wave 2.

Employing stratified sampling has many advantages in a large research project:

- This method of sampling helps to ensure that subgroups and minority groups will be represented in the survey

- It is operationally more efficient, in terms of both time and money, compared to random proportional sampling techniques.

- Stratified samples deliver smaller sampling errors than pure random samples (Cochran, 1963).

Ethical Considerations

Being an analysis of existing databases, the current study need not address BGSU guidelines for social science research on human respondents. The original authors had taken care of permissions and ensuring due care as to the handling of personal information.

Variables

The NLSAH explored relationships among many different variables, including education, sex, pregnancy, relationships, children and parenting, daily activities, and in-school networks. For the purpose of this study, depression is the dependent variable (DV). Measures of depressive symptoms were collected during the adolescent in-home interview at Wave 1 and were operationalized with scores for the modified version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Ornelas, Perreira & Ayala, 2007). A score is calculated by summing responses to how often the adolescents experienced 19 different symptoms that have been shown to be linked with depression within the past week. The response categories ranged from 0 to 3, with 0 meaning “never” or “rarely” and 3 meaning “most or all of the time” (Ornelas, Perreira & Ayala, 2007). Questions 4, 8, 11, and 15 were reverse coded to minimize “holistic bias,” the tendency to stay with one answer straight down a survey checklist. A score of 16 or above indicated that the respondent was suffering from clinical depression.

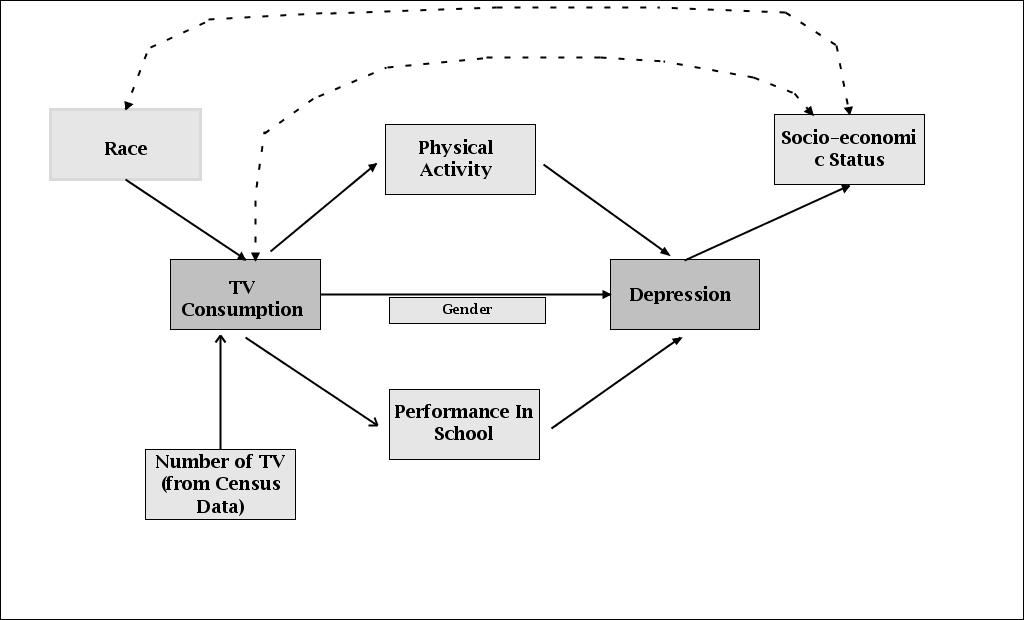

For this study, the main independent variable is television consumption (found under the questions that measure daily activities). Structural equation modeling will be used to test for positive links among moderating or intervening variables defined in Figure 2 below. At this stage, a possible suppressor could be the age of the respondent since prior research has shown that age can positively influence television consumption. On the other hand, family income (and the corollary factor of multiple TV set ownership) could be a reinforcer of TV habituation. It can be argued that adolescents from lower-income households will spend more time watching television because they do not have other options to entertain themselves, such as video games or spending time outside of the house with their friends. In turn, moderate levels of physical activity – whether in the form of structured exercise, bodybuilding, or participation in team sports – and above-average academic achievement may be expected to show an inverse relationship with both TV consumption and depression. Ethnicity may be a moderating factor, if only because average annual incomes are known to be lower for minorities (except Asian-Americans).

References

- Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66, 3-11.

- Bandura A. (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Berkowitz, J. E. L. (1994). A priming effect analysis of media influences: An update. In: Bryant J, Zillman D, eds. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum: 43–60.

- Brent, D. A. & Birmaher, B. (2002). Adolescent depression. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347(9) 667-671.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2008). American time use survey summary.

- Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (n.d.). National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. [Data file].

- Centers for Disease Control (2005). Deaths: Leading causes for 2002. Vital Statistics Reports, 53 (17), 13.

- Cochran, W. G. (1963). Sampling techniques. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & sons.

- Cohen, J., & Weimann, G. (2000). Cultivation revisited: Some genres have effects on some viewers. Communication Reports, 13, 1-17.

- Davison, W. P. (1983). The 3rd-person effect in communication. Public Opin Q, 47: 1 –15.

- Economist.com (2007). Couch potatoes. Web.

- Gerbner, G., & Gross, L. (1976). Living with television: the violence profile. Journal of Communication, 26, 172-199.

- Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1994). Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective. In: Bryant J, Zillman D, eds. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum:17–41.

- Gunter, B. (1994). The question of media violence. In J. Bryant & D. Zillman (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research. (pp. 163-212). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Harris, K. M., Halpern, C. T., Smolen, A. & Haberstick, B. C. (2006). The national study of adolescent health (ADD Health) twin data. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 9(6), 988-997.

- Hughes, M. & Peterson, R.A. (1980). Television watching and social-political attitudes: An empirical study of the effects of sexism, racism, conservatism, alienation, quality of life indicators and attitudes about violence. Unpublished paper.

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Hoff,T., Green, L., & Davis, J. (2003). National survey of adolescents and young adults: Sexual health knowledge, attitudes, and experiences.

- Mitroff, D. (2004) Prime-time teens: Perspectives on the new youth-media environment.

- National Institutes of Mental Health (1982). Television and behavior: Ten years of scientific progress and implications for the eighties. Summary Report, DHHS publication no. ADM 82-1195. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Ornelas, I. J., Perreita, K. M. & Ayala, G. X. (2007). Parental influences on adolescent physical activity: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 4(3), 1-10.

- School officials identify adolescent MH problems as one of the most serious issues (2004). Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, 1,7.

- Steele, J.R., & Brown, J.D. (1995). Adolescent room culture: Studying media in the context of everyday life. J Youth Adolesc, 24 : 551 –576.