Introduction and Statement of the Problem

State of the Art Summary

The global community is becoming increasingly concerned about the environmental changes together with social and economic problems. UNEP (2020) identified 2019 as the year when the past harms to nature have caught up with the present, and humanity had to deal with the significant impact of climate change in forms of weather disasters. In 2020, all the countries felt how environmental problems made the response to COVID-19 pandemic less efficient. Thus, the call for sustainable development became even more urgent as the number of people affected by ecological issues increases.

The idea behind sustainable development is satisfying the current needs of humanity without interfering with future generations’ ability to meet their needs (United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development [UNWCED], 1987). The most recent UN conference on sustainable development identified seventeen goals in different spheres, including economics, equality of opportunity, healthcare issues, and food supply. Achievement of sustainable development is possible only with the engagement of all stakeholders, including universities and other education facilities, financial institutions, government, business, non-government organizations (NGOs) and communities.

Responsible leadership arises in the practice of corporations and other organizations in connection with the phenomenon of social responsibility of the company. The essence of such responsibility is that the company must take into account the interests of many parties in the implementation of activities, as well as comply with the norms of society (Maak & Pless, 2012). In the literature, it is proposed to decompose the concept of “responsible leadership” into formulas that reflect those areas to which organizations are responsible, and therefore their leaders are responsible. Richardson (2015) argues that there are four classes of responsibility for a company in relation to society: economic, legal, ethical, and what he called “discrete responsibility.” In this case, responsible leadership can be expressed as a formula:

Responsible leadership = f (Economics, Politics, Ecology, Morality).

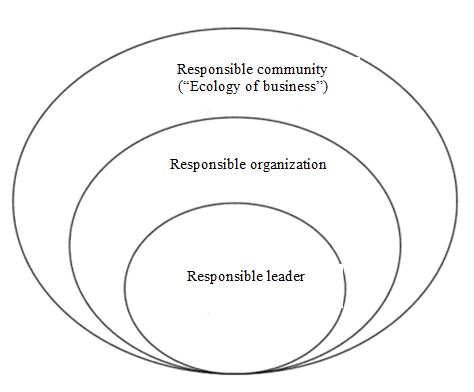

This formula of responsible leadership is interpreted as follows: responsible leadership is a function of the interaction of the firm and society in the economic, sociopolitical, environmental, and moral spheres (Richardson, 2015). Responsible leadership can enrich and align each of these areas. Responsible leadership can also be seen as a function of the personality of the leader (who adheres to the principles of responsibility when making decisions), a responsible company, and a responsible group of all stakeholders surrounding the organization (investors, consumers, competitors, regulators, etc.). This aggregate responsibility of all participants in the business world can be called “business ecology” and displayed using the scheme shown in the figure below. This figure shows a holistic view of responsible leadership, in which all its participants are in the process of communication, seeking and moving towards equality, mutually participating in the process of contributing to the achievement of sustainable development goals.

The basis of modern business ethics is considered to be the social contract and social responsibility of the company. The social responsibility of entrepreneurs consists not so much in generous donations for the education of the people, but in the organization of a business that would provide the working people with a stable property status, social protection, opportunities for education and spiritual growth (Parry et al., 2019). Social responsibility is a concept that reflects the voluntary decision of an organization to participate in the improvement of society and the protection of the environment. This is a set of obligations that an organization must fulfill in order to strengthen society. Today, not all companies adhere to business ethics and social responsibility included in this concept (Parry et al., 2019). This is due to the fact that with a very developed competition, many companies begin to chase not the quality of the goods and the number of consumers, but the maximization of profits. Any created commercial organization has a primary goal in its creation to enrich itself.

However, in the pursuit of revenue, many organizations cease to comply with any moral or social principles: for example, they pollute the environment, or the quality of the goods begins to deteriorate. This often happens in large companies with little competition in the market. Thus, the business etiquette of the company suffers, enterprises simply begin to forget about their responsibility to society. In addition, opponents of the socio-ethical approach believe that this kind of business policy primarily leads to a violation of the principle of profit maximization (Parry et al., 2019). Their opinion is based on the fact that funds allocated for social needs are costs for the enterprise. Among the arguments “against” also highlight the lack of ability to resolve social problems. The company’s staff lacks the experience to make meaningful contributions to solving social problems. The presence of such opposing arguments explains the lack of an unambiguous attitude to social responsibility. This is a very critical issue that needs to be addressed.

As a solution, he proposes a model of responsible leadership, thanks to which it is possible to motivate managers and employees and make them responsible for their actions. Motivation can be both positive and negative. The pessimistic direction and motivation is mainly widespread in the world. For example, when a large corporation takes on the problem of the environment and how to overcome critical points, any presentations or projects touch on the topic of disasters. If the impact will show, for example, how “profits and the number of consumers will fall” then the opposite is possible (Parry et al., 2019). With the right motivation, the focus of companies on maintaining social responsibility will only grow. Perhaps it will even become a mandatory feature, as it is now beginning to spread in foreign companies.

Despite the fact that the state supports social policy and tries with all its might to maintain and control the market, risks are possible. Excessive bureaucratization and corruption in public authorities are also common, due to which the state closes its eyes to the lack of social responsibility that all companies should theoretically bear. To reduce such effects, attention should be paid to leadership in the field of ethics and social responsibility. Organizations and businesses should follow certain rules and try to engage in non-profit activities whenever possible. Any person can understand that they do not want to give their profits to the social good or the state, while feeling great risks and costs (Parry et al., 2019). But if organizations do not trust charitable foundations or the state, then they should take the initiative in their own hands and begin leadership activities to effectively support social culture. The more numerous the composition of the middle or upper strata of the population, the better it will be for producers, because the product will sell even better (Parry et al., 2019). Moreover, at the mention of the company, people will have positive associations.

If the society begins to feel that it helps the society and does it also for its own benefit, then the company’s fame is ensured. For well-known companies, Intel is a good example of a leadership motivator. In 2008, Intel received the Business Ethics Award for Leadership in Corporate Social Responsibility (Parry et al., 2019). This is the first time this award has been established, and Intel Corporation has thus become its first laureate. Business Ethics magazine, in the words of its editor-in-chief Marjorie Kelly, “recognized Intel’s leadership and success in the field of business ethics and corporate social responsibility” (Parry et al., 2019, p. 197). It should be clarified that the corporation participates in more than 50 socially responsible mutual funds of various kinds. In the world, only a few companies are so actively engaged in this kind of activity. In addition, the company’s achievement is that, as part of the worldwide Global Reporting Initiative, Intel was one of the first organizations in the United States to introduce the practice of reporting on its activities to ensure corporate social responsibility and environmental protection (Parry et al., 2019). Such a reputation immediately begins to positively influence consumer psychology.

Today, corporate leaders of NGOs are required, first of all, to be able to work effectively in conditions of uncertainty and to coordinate the interests, needs, and requirements of all stakeholders. Responsible leaders recognize, respect, and reconcile the multiple interests, needs, demands and conflicts that arise between employees, customers, suppliers and other contractors, different communities, other non-governmental organizations, regulators, the environment and society at large (Lawrence & Beamish, 2012). In an era of economic globalization, corporate leaders find themselves in a dynamic and complex multicultural business environment characterized by increasingly close interconnections between technology, people, organizations and society at large. Leadership models created for more traditional and stable eras have lost their relevance. Leadership in the conditions of widespread dissemination of the idea of sustainable development and related regulatory and advisory norms should be systemic and flexible enough to adapt to the extreme complexity and dynamics of the external environment, as well as the peculiarities of the internal environment of NGOs.

It is interesting to note that among non-governmental organizations, the World Wildlife Fund (28% of expert votes) and Greenpeace (18% of expert votes) continue to hold global leading positions (Schinzel, 2018). The experts highly appreciated their efforts to effectively engage stakeholders and actively interact with other organizations. This is clear evidence of the importance of effective leadership in contributing to the achievement of sustainable development goals. In addition, NGO leaders have, one might say, a “double” responsibility, since by their example they should inspire leaders of commercial organizations, their employees, and other citizens to apply the principles of CSR, corporate citizenship and responsible leadership on a large scale. In these conditions, the interaction of NGOs with communities is of particular importance, determining the need to identify and clarify the relationship between NGOs and the community in achieving sustainable development.

Recently, scholars began to realize the growing impact of sustainable development on NGOs. Thus, a phenomenological approach will be used to establish causal relationships between the sustainable development of an NGO and its relationship with the community. The study uses semi-structured interviews to answer research questions formulated to acquire a holistic understanding of the relationship between NGOs and the community in building sustainable development.

Background Information

Environmental Concerns

The global community is experiencing a significant rise in concern about environmental changes. According to the United Nations environment report, the global temperature has risen by 1°C compared to the pre-industrial era, causing significant economic losses associated with environmental and weather disasters, such as heatwaves and wildfires, hurricanes, and droughts (UNEP, 2019). The UN’s under-secretary-general and UNEP executive director wrote that 2019 was the year “when our past finally caught up with us and science provided an unambiguous call for urgent action” (UNEP, 2020, p. 3). In 2019, the world continued to see the devastating effects of mindless consumption resulting in storms, melting of ice sheets, and floods (UNEP, 2020). Even though most governments understand the importance of reducing the impact on the ecology of the planet, most of them fail to accomplish it. In 2019, only the countries of the European Union (EU) were able to slightly decrease greenhouse gas emissions, while other top greenhouse-gas emitters failed to do so (UNEP, 2019). If the countries continue to ignore global environmental emergencies, the number of natural disasters, threats to public health, and biodiversity loss will continue to grow rapidly.

In general, there are ten crucial environmental problems most commonly mentioned by scholars and organizations. They include climate change, pollution and associated health problems, protection of oceans, energy consumption, sustainable food model, protection of biodiversity, sustainable urban development and mobility, water scarcity, overpopulation and waste management, and extreme meteorological phenomena (Abernethy, Maisels, & White, 2016). All these problems are interconnected, and their root cause is human activity. Since humanity is responsible for environmental changes, the issues mentioned above can be addressed by altering human activity on all levels. UN (2020) calls on all the countries for immediate action to protect the planet and slow down or reverse the current processes leading to environmental problems.

“The main challenge for the development of society,” wrote Mahbubul-Haq in the first Human Development Report in 1990, “is to create an environment conducive to people enjoying long, healthy, and constructive lives” (ul-Haq, 1995, p. 19). According to him, the true wealth of nations is people. At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, the generally recognized supranational task of the world community was the movement towards sustainable development, which is understood as the preservation of the environment in unity with social and economic well-being in the interests of the present and future generations. Today ensuring sustainable development is impossible without a radical renewal of the management of social processes, norms and traditions of the community, without replacing the market economy with an economy of values. The development of an optimal scheme of social relations in the interconnected world with a limited resource base has moved from the plane of scientific discussions to the plane of urgent practical problems. However, despite certain positive results achieved in a number of highly developed countries, a radical change in social management did not occur. There are many reasons for this, including the underdevelopment of the fundamental foundations of leadership by sociological science, the transition period from the modern era with a goal-oriented community to postmodern with a human value orientation, interpersonal relations, and interaction between society and nature.

Based on the law of proportional development of social systems, for the system to acquire the properties of sustainable development, a relative change in all elements of this system is necessary. Violation of this law, regardless of the subject’s intentions, leads to the subsequent inhibition of development, followed by destruction of the entire system (David, 2012). There is no alternative to sustainable development, but today the participation of all actors in the UN Global Compact is insufficiently coordinated. There was no proper transition from discussions and concepts to the level of methodological and technological support of distributed leadership for value-oriented social management, a sustainable “economy of values” (Sachs, 2015). In addition, the corresponding system of indicators has not been fully formed, which often leads to sustainable development management based on common sense management, increasing entropy.

Meanwhile, at the level of organizations, the concept of sustainable development actually coincides with the implementation of the concept of management based on knowledge and CSR, and at the level of the individual, the leader – with the understanding of human dignity and the resulting value orientations in the “nature-society-human” system. Today, there is no doubt that any conceptual scheme can remain unrealized if the organization does not have dynamic leadership that is optimally distributed among all personnel at all levels of the organization, and this applies to both the micro level (that is, the company level) and the macro level (community). In this regard, an in-depth understanding of the theoretical foundations of leadership in the context of providing an effective relationship between NGOs and the stakeholders in building sustainable development, when leadership acts as a link between human and social capital, the main element of social management, seems to be highly expedient and urgent.

Sustainable Development

Defining deep roots and the very essence of sustainable development, one can say that this concept is the key to resolving the environmental issues discussed above. In 1987, the UNWED (1987) defined sustainable development as development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ ‘ (para. 27). Sustainable development principles require that more economically advantageous people adopt life-styles within the planet’s ecological means (UNWCED, 1987). The changes should be made in the amount of consumed resources to ensure equity (UNWCED, 1987). In order to achieve sustainable development, the UN (2015) set seventeen comprehensive goals associated with 163 targets to achieve by 2030 to address the problems related to poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace, and justice. Even though the new agenda that came in effect in 2016 is a set of intergovernmental commitments, it gained support from many actors, such as public policy bodies, NGOs, and many public sectors and private sector organizations (Bebbington & Unerman, 2018). Sustainable development goals are commonly referred to as “the Global Goals” (Bebbington & Unerman, 2018).

The UN’s agenda prioritizes changes associated both with the environment and the global community. All the seventeen goals are briefly outlined below:

- No poverty: making economic growth more inclusive to provide sustainable jobs and promote equality;

- Zero hunger: decreasing food waste and support to local agricultural producers;

- Good health and well-being: promotion of vaccination and preventive care;

- Accessible education: helping to educate children in communities around the globe;

- Gender equality: empowering of women and girls to ensure their equal rights;

- Clean water and sanitation: promotion of efficient water use;

- Affordable and clean energy: promotion of utilization of only energy-efficient appliances and light bulbs;

- Decent work and economic growth: creating job opportunities for youth;

- Industry, innovation, and infrastructure: funding projects that provide necessary infrastructure and innovation;

- Reduction of inequality: supporting the marginalized and disadvantaged;

- Sustainable cities and communities: providing access to basic services, energy, housing, transportation, and more for everyone;

- Responsible consumption and production: recycling paper, plastic, glass, and aluminum and using recyclable materials;

- Climate action: action to stop global warming;

- Preservation of oceans: avoiding pollution of the world’s essential resource;

- Preservation of life on land: carefully managing forests, combating desertification, halting and reversing land degradation, and halting biodiversity loss.

- Peace justice and strong institutions: building effective, accountable institutions at all levels.

- Partnerships: revitalizing the global partnership for sustainable development (UN, 2015).

As seen from the goals described above, sustainable development does not mean only environmental sustainability. Instead, the UN’s agenda aims at addressing all the problems that may prevent future generations from meeting their needs. However, even though the idea behind the goals is evident, it is unclear how the UN’s directives should be translated into action. In other words, the role of these goals may seem vague for an unprepared reader. According to Leal Filho et al. (2018), sustainable development goals are important for two central reasons. First, clear articulation of priorities revitalized researchers worldwide to work together to find practical solutions for the fundamental problems before humanity (Leal Filho et al., 2018). Scholars working in one of the seventeen areas mentioned above have improved chances of receiving financial and institutional support to close the current gaps in knowledge that prevent sustainable development (Leal Filho et al., 2018).

Second, the fact that the UN set a relatively tight timeframe for achieving the goals added a sense of urgency to the problem (Leal Filho et al., 2018). This urgency created an imperative not only for researchers but also for policymakers and other actors to put the results of the latest research into use (Leal Filho et al., 2018). Sustainable development goals provided significant incentives for institutions and research teams to collaborate to benefit people, partnerships, justice, prosperity, dignity, and the planet.

Achieving the goals set by the UN’s framework is impossible without engaging all the stakeholders to work efficiently together. The benefits of engaging all the stakeholders are evident: it leads to achieving maximum productivity and effectiveness, it ensures equity in decision-making, and it allows the ideas to be tested before implementation (Leal Filho & Brandli, 2016). Without the engagement of all stakeholders, it is impossible to reach the balance of rare and human resources (Wojewnik-Filipkowska & Węgrzyn, 2019). However, there are various barriers that abstract the engagement of all stakeholders at a needed level. First, even though there are many methods for stakeholder engagement, the current engagement process lacks a unified scheme (Leal Filho & Brandli, 2016). Second, groups of stakeholders have varying interests, which may contradict each other leading to a conflict of interest (Kent, 2010). Third, different stakeholders have insufficient capabilities, as the transition to proactive forms of stakeholder management requires additional resources (Rhodes, Bergstrom, Lok, & Cheng, 2014). Fourth, a growing number of stakeholder participation leads to stakeholder fatigue and cynicism (Leal Filho & Brandli, 2016). Fifth, all the steps of governments require disclosure, which may lead to additional risks for them due to intense scrutiny (Kent, 2010). Finally, some stakeholders are challenging to have a direct dialog with for various reasons (Leal Filho & Brandli, 2016). However, these barriers are to be addressed to ensure that all sustainable development goals are achieved.

Changing Role of Governments

While the engagement of all stakeholders is crucial, governments play a central role in facilitating sustainable development. UN (2015) recognizes the critical role of governments in engaging citizens and stakeholders and providing them with relevant information on all aspects of sustainable development. In general, governments’ central roles are policy development, regulation, facilitation, and internal sustainability management (Young & Dhanda, 2013). When developing policies, governments need to set and prioritize realistic goals aligned with the overall strategy to achieve sustainable development (Young & Dhanda, 2013). As facilitators, governments stimulate breakthroughs and set boundaries for other stakeholders by establishing clear criteria for governmental support and creating financial and non-financial incentives (Young & Dhanda, 2013). Under regulation, scholars understand all governments’ initiatives in legislation, administration, and enforcement used to set legal frameworks supporting sustainable development (Young & Dhanda, 2013). Finally, when managing internal sustainability, governments should promote social responsibility among all governmental bodies (Young & Dhanda, 2013). Currently, however, governments started to realize the wide variety of roles they play beyond the central ones described above.

When cooperating with other stakeholders, governments need to help set vision and strategy to promote sustainable development. Second, governments should continuously improve their environmental performance to set an example for other stakeholders (Kent, 2010). Third, governments need to create “open, competitive, and rightly framed markets that would include pricing of goods and services, dismantling subsidies, and taxing waste and pollution” (Young & Dhanda, 2013, p. 217). Fourth, governments should commit to fiscal reforms that amend businesses for their commitment to sustainable development goals (Young & Dhanda, 2013). Finally, governments should understand their role as a catalyst that should promote innovation on all levels, as sustainable development demands much change to be adopted (Young & Dhanda, 2013). Thus, the role of governments is shifting towards close cooperation with different stakeholders.

Non-government Organizations

One of the most controversial stakeholders in sustainable development is NGOs, as their role in sustainable development initiatives is unclear. NGOs include a wide variety of organizations, in particular, private voluntary organizations, civil society organizations, and nonprofit organizations (Young & Dhana, 2013). While during the first sustainable development conferences organized by the UN acknowledged states as primary actors, current research started to accept the idea that the decision-making process is no longer the responsibility of governments (Pacheco-Vega, 2010). NGOs started to play a significant role in international conferences dedicated to sustainable development. Evaluating the degree of NGOs’ influence on sustainable development is a challenging task that is yet to be achieved. At the same time, as it is evident from the features of leadership with regard to sustainable development, considering this influence in frames of NGOs leadership practices can serve as a basis for phenomenology analysis and constructivist paradigm application.

NGOs are believed to be one of the most active groups of partners playing supportive roles in the implementation of sustainable development initiatives (Muazu & Abdullahi, 2019). Simultaneously, they are more effective than governments “to get attached with the grass root level developmental initiatives” (Muazu & Abdullahi, 2019, p. 1). While numerous studies appeared not able to evaluate how many governments failed to acknowledge and appreciate the impact of NGOs on sustainable development, numerous studies confirm that their impact keeps growing worldwide (Muazu & Abdullahi, 2019). According to Sustainability Degrees (2014), influential NGOs that facilitate the achievement of sustainability goals outlined by the UN are Ceres, Conservation International, Doctors without Borders, Greenpeace, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and others. All the organizations have different agenda supporting the achievement of one or several of the seventeen goals. For example, Ceres is a sustainability nonprofit organization that promotes sustainable business practices and solutions by working with companies around the world (Sustainability Degrees, 2014). It is worth noting that the above firms have a close relationship with society, since they promote and study the interests of citizens. This is evident in their practice of interacting with community leaders, polling citizens on certain topics, and tailoring their actions in line with the expectations of the majority (Leinarte, 2021). By exercising responsibility, these firms create quality and lasting credibility. It is realized in the opinion among people, for example, that WWF serves to protect humanity and animals from disasters and aims to improve the world (Leinarte, 2021). The vision of the organization is to transform the economy to build a sustainable future (Ceres, 2020). The company developed a unique change theory that aims at moving investors, companies, policymakers, and other influencers to act on four global challenges: climate change, water scarcity and pollution, inequitable workplaces, and outdated capital market systems (Ceres, 2020). The company utilizes Ceres Roadmap for Sustainability as a comprehensive framework for leading change with a special commitment to inclusion and equity (Ceres, 2020).

Relationship between NGOs and Communities

One of the NGOs’ central roles mentioned above is to interact with local communities to achieve sustainable development. Bashir (2016) defines community development as “voluntary participation of local community individuals in a systematic process to bring some desirable improvements, especially health, education, housing, recreation in the targeted community” (p. 124). Today, community development is seen as the central practice in social development as it creates social capital and supports the self-dependency of communities (Bashir, 2016). Therefore, local communities often benefit from participating in the activities and programs designed by NGOs. The benefits can be financial; as local representatives may start working for the NGOs. Thus, NGOs can be seen as potential employers for the representatives of the local community, which contributes to the overall financial sustainability of communities. However, this impact is rather small in comparison with other spheres of influence.

According to Bashir (2016), when interacting with local communities, NGOs seek to achieve the following goals:

- Improve the various aspects of community well-being including health, education, housing, and recreation;

- Motivate communities to create and implement community-based plans to address their issues;

- Help the communities identify their strengths and resources to implement the plans;

- Develop community leaders through employment, leadership programs, and participation in volunteer programs.

- Build cooperation between communities and governments;

- Develop functional community groups and organizations.

However, community development is a laborious endeavor that requires a number of planned interventions strategically aligned to meet the needs of every specific community. The implementation of these interventions is impossible without positive relationships between the NGOs and the community. However, some communities have a strong resentment towards NGOs, which undermines the achievement of sustainability goals. For example, in Afghanistan, citizens have developed a strong resentment towards NGOs (Jelinek, 2006). The root cause of negative relationships is often general distrust of foreigners and lack of information about NGOs’ zones of responsibility (Jelinek, 2006). Citizens may blame NGOs for the absence of effective food distribution or the lack of means to assess the needs of the education system, which is the government’s responsibility (Jelinek, 2006). The dysfunctional relationship between community and NGOs prevents effective cooperation and achievement of sustainability goals. In turn, these dysfunctional relationships represent the consequence of lack of proper leadership in NGOs, inability to apply stakeholder management principles. Like business companies working on increasing customers’ loyalty, without which they will not have sound market success, NGOs also should work in this direction, trying to achieve maximum possible loyalty of communities, without which they will not be able to meet their goals in contributing to sustainable development.

Statement of the Problem

Sustainable development involves multiple stakeholders that need to operate together to achieve the 17 goals outlined in the UN’s agenda. Thus, the roles of every stakeholder need to be clear in order to achieve maximum efficiency of efforts. Currently, the roles of different stakeholders are often unclear, making the collaboration complicated. Therefore, defining the roles of various stakeholders is a matter of increased importance for achieving sustainable development worldwide. Currently, NGOs have a significant impact on all aspects of sustainable development through direct and indirect interaction with governments and communities. Even though the impact of NGOs on sustainable development is a matter of increased attention from scholars, it is unclear how the relationship between NGOs and the community affects sustainable development.

Lack of a clear understanding of the role of relationships between different stakeholders may pose significant problems for policymakers and actors. Without refined knowledge of the matter, NGOs will face difficulty engaging the community to become self-sufficient. Issues like general distrust to foreigners and lack of comprehensive communication plan, which are in turn the “derivatives” of not proper leadership, may lead to decreased efficiency, which can prevent the society from achieving sustainable development goals.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of the article is to analyze and establish the cause-and-effect relationships that ensure the sustainable development of NGOs. In order to achieve the purpose, the following objectives were set: 1) Identify community and NGO interactions; 2) Establish goals and prospects for sustainable development and activities of NGOs; 3) Consider potential losses and risks when building unfavorable strategies; 4) Establish a correlation between sustainable development and the community related to NGOs; 5) Establish the most optimal type of leadership for these enterprises, its features and potential.

The present research aims at answering the following research questions:

- RQ1. What are the factors contributing to functional relationships between NGOs and communities?

- RQ2. What are the factors contributing to dysfunctional relationships between NGOs and communities?

- RQ3. What is the impact of functional relationships between NGOs and communities on achieving sustainable development?

- RQ4. What is the impact of dysfunctional relationships between NGOs and communities on achieving sustainable development?

- RQ5. What is the role of leadership in NGOs’ stakeholder management (i.e. functional community and sponsor relationship)?

- RQ6. What is the role of leadership in contributing to sustainable development?

- RQ7. What steps should NGOs take to adopt leadership practices for building functional relationships with communities?

The research questions will be answered by conducting semi-structured interviews with stakeholders, NGO managers/leaders and community representatives. The study synthesizes the experience of experts to acquire a holistic understanding of the relationship between NGOs and the community in building sustainable development.

Definitions

- Non-governmental organization (NGO) – a private organization that aims at reducing human suffering by addressing one or a combination of sustainable development problems (Bashir, 2016).

- Sustainable development – development that meets humanity ‘s needs without compromising the needs of future generations (UNWCED, 1987).

- Functional relationship – generally positive relationships that promote effective functioning of all stakeholders.

- Dysfunctional relationships – generally negative relationships that obstruct the effective functioning of all stakeholders.

- Stakeholder Management

- Agile leadership – the practice of creating change that contributes to building an agile organization.

Literature Review

Sustainable Development Paradigm

Today, the global problem of climate change and the deterioration of social conditions for mankind is not a problem of any particular state, not of any region or even a continent, but a problem of the entire world community. One of the most vivid examples of how human activity affects public health is the COVID-19 pandemic. While a direct link between the disease and climate change was not established, there are clear indirect correlations between the two matters. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), climate change made the response to the coronavirus epidemic less efficient. Climate change undermines the state of health of all people worldwide, creating significant pressure on healthcare systems. Moreover, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) reports that the majority of deaths among COVID-19 patients was caused not by the virus, but by the aggravation of pre-existing conditions, such as severe heart problems, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, sickle cell disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Additionally, WHO (2020) mentions that all pandemics originate in wildlife, and increased human pressure on the environment and contact with animals positively affects disease emergence, especially infections.

Another problem is water scarcity caused by global climate change. Around 80% of the global population experience the direct effects of water scarcity (WHO, 2020). Almost 25% of all healthcare facilities on the planet lack basic access to clean water, which directly impacts services provided to over 2 billion people (WHO, 2020). In five years, half of the world’s population will live in water-stressed areas due to devastating livestock farming, which is responsible for 29% of worldwide water consumption (Greenpeace, 2020). Thus, climate change affects public health in a variety of obvious and subtle ways.

The environmental emergency is also caused by a significant decrease in biodiversity reported by numerous government and non-government organizations. UNEP (2020) states that the average abundance of species has fallen by at least 20% since 1900. In particular, the number of species of amphibians decreased by 2.5%, mammals – by 2%, birds – by 1.75%, reptiles – by 1.1%, and fishes – by 1% (UNEP, 2020). If biodiversity continues to decrease at the current rate, it can be a significant threat to the sustainability of numerous ecosystems, as different species often play unique roles that humans are unable to identify (Lohbeck, Bongers, Martinez‐Ramos, & Poorter, 2016). Even though not all species currently have an equal effect on ecosystems due to varying dominance levels, given the spatial and temporal turnover in species dominance, all species may have a significant impact on ecosystems (Lohbeck et al., 2016). Thus, the global community needs to address the problem of shrinking biodiversity without hesitation to avoid adverse outcomes.

Realizing the tendency of the experienced needs to constant growth and modification, and the possibilities for their satisfaction, on the contrary, to a steady narrowing, given that economic activity leads not only to the depletion of resources, but also to environmental pollution with industrial waste, mankind was forced to admit the formation of serious global problems that threaten not so much its progress but rather its survival. At the same time, most threats to the survival of mankind (land degradation, environmental pollution, loss of biological diversity, military conflicts, problems of poverty and social inequality, terrorism) not only continue to be relevant, but are also growing and aggravating. As noted in most studies on sustainable development, all this indicates a serious crisis situation, the way out of which the world community sees in a progressive transition to sustainable development, which requires the unification and coordination of efforts of all countries (Robertson, 2017). Given these circumstances, the modern world is trying to move from an exhausted top-down model of socio-economic development, which is based on spontaneous, unstable activities that negatively affect the environment and undermine human health, to a promising ascending model, characterized by sustainable progressive dynamic development, contributing to improving the quality of life and the environment.

Sustainability is a popular topic in modern business discourse, incorporated into activities at various levels. With varying degrees of awareness, companies are beginning to understand that global emissions – joint exceeding of the planet’s environmental limits – is a serious threat to organizations, society, and the Earth itself (Robertson, 2017). Progress has been made, and in many ways continues to grow, but the complexity of sustainable development issues is becoming increasingly evident, together with the importance and need for large-scale change to address these issues.

The concern of the world community about the state of these problems has led to the need to revise the existing doctrine of socio-economic development, develop a new paradigm and create international scientific organizations for the study of global processes, such as the Club of Rome, the International Institute for Systems Analysis, and the International Federation of Advanced Research Institutes.

The next stage in the formation of a new economic paradigm as a paradigm for sustainable development was the United Nations Conference on the Environment (Stockholm, 1972), which resulted in the development of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). In the same year, at the request of the Club of Rome, the study The Limits to Growth was published. In this document, in accordance with the idea of the transition from extensive economic growth (by involving additional resources in economic activity) to intensive growth (due to the rational, more efficient use of existing resources) and the new world economic order, twelve scenarios for the development of mankind based on various resource provision alternatives were presented (Hess, 2016). However, the very concept of sustainable economic development has entered scientific circulation since the publication of the report Our Future in 1987 by the International Commission on Environment and Development. The report formulated the thesis of a new era of economic development, safe for the existence of mankind and the environment. In this regard, the researchers note that it is about development, which implies a model of socio-economic development in which the satisfaction of the vital needs of the current generation of people is achieved without future generations being deprived of such an opportunity due to the depletion of natural resources and environmental degradation (Hess, 2016). Finally, as the main strategy of the current stage of the functioning of the world economy, as shown by modern research, sustainable development was first identified at the UN Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro, 1992) (Sachs, 2015). The conference made a historic decision to change the direction of the evolution of the entire world community, demonstrating the awareness of the pernicious nature of the traditional path, which is characterized by instability, fraught with economic crises and man-made disasters.

Many authors, defining the main signs of the failure of the existing paradigm of the development of modern civilization, note its inability to solve the problems faced by mankind, expanding economic activity and exhausting the possibilities of nature to provide this activity with the necessary resources. In this regard, they point to the need for the formation of a new economic theory that can correctly explain and propose directions for correcting the socio-economic behavior of participants in economic activity in the context of an increasing resource shortage and decreasing environmental safety at all its levels. Such a theory, in their opinion, should be namely the theory of sustainable development (Ashmarina & Vochozka, 2019).

Sachs (2015) notes that the countries that created the welfare state have made some progress in adapting industrial civilization to the requirements of human existence. However, the fundamental problem remained, and neoliberal market fundamentalism did a lot for the new ‘deification’ of the economy (Ashmarina & Vochozka, 2019). The authors do not see a worthy alternative in economic development among the modern most dynamic development models, citing as an example the anti-sustainable Chinese modernization, which puts economic growth and mass consumption at the forefront and creates a modern and far from environmentally friendly economy in the most populous country in the world (Hess, 2016). Exploring the problems of sustainable development and arguing within which economic system (model) it is possible, the experts write that given that the Agenda 21 contains a steady circulation of economic and market terms, it can be assumed that the economy of sustainable development is not identical to the market economy though uses its tools (Tietenberg & Lewis, 2019). Indeed, the economy of sustainable development is replacing the traditional (market) economy. In accordance with the main thesis of Agenda 21 about the discrepancy between traditional ideas about economic growth and emerging patterns of consumption and production that meet the existing needs of mankind, and the conclusions of the above-mentioned scientists, the following basic principles of sustainable development can be formulated (Bebbington & Unerman, 2018):

- Ethical norms based on respect and care for each other and for the planet as a whole are the basis for the sustainable development of modern society.

- Improving the quality of life, the indicators of which should be, in accordance with the United Nations Development Program, life expectancy, health, education, income. At the same time, the quality of life should be determined by such important factors as lifestyle, anthropogenic activity (the nature of production and consumption) and the course of natural processes.

- Preservation of the vitality and diversity of all life on earth. This principle requires the formation of a life support system that makes our planet livable, the conservation of biological diversity, and the guarantee of sustainable use of renewable natural resources.

- Minimizing the use of non-renewable resources. Work in this direction involves the all-round development and application of resource-saving technologies by countries of the world, the expansion of the use of secondary waste in economic activity, and the switch (where possible) to renewable resources.

- Encouraging the interest of society and its members in preserving the environment. Realizing this principle, society should in every possible way stimulate the implementation of environmentally responsible economic activities and more fully express its concerns and interests in preserving the living environment of mankind.

- Integration of the processes of socio-economic development and environmental protection, which provides for the formation and implementation of economic policy aimed at the rational use of resources, and constant monitoring of compliance with the proper level of environmental safety.

In 2015, the member states of the United Nations adopted a document entitled “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (“Agenda 2030”), which enshrined the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as the main guidelines for the evolution of the world community for the next fifteen years. This international event became evidence that the concept of sustainable development has won the status of a key and backbone theory of global development in the 21st century. The expansion of the range of challenges and threats that humanity has faced in the new millennium has led to the expediency of a “triune” interpretation of sustainable development, providing for the need to simultaneously address social, economic, and environmental problems at the national and global levels.

The Sustainable Development Goals, formulated in the updated UN agenda, formalized the “threefold” approach to this concept. Thus, humanity is faced with the urgent task of looking for additional sources and innovative approaches to financing development and ensuring “socially inclusive” and environmentally sustainable economic growth (Robertson, 2017). In this regard, the contribution of the private sector, NGOs, and local communities to the implementation of the SDGs at the global level takes on a special role, which is emphasized in the documents adopted by leading international organizations in recent years. In turn, this determines the need to apply a stakeholder approach to sustainable development issues. At the same time, there is currently a significant lack of serious academic research in science devoted to the problems of interaction between the state and the private sector, aimed at the practical implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as assessing the role of various stakeholders, including NGOs, in financing and ensuring global development. Meanwhile, as shown below, at the country level, a number of practical steps are being taken to involve stakeholders in addressing sustainable development issues.

Stakeholder Approach and the Role of HGOs in Building Sustainable Development

The sustainability goals help all stakeholders acquire a unified understanding of the situation and the way to approach it. Even though many leaders understand the negative impact of human development on the environment and the society, they often do not know how climate change, shrinking biodiversity, water scarcity, and poverty are just symptoms of “an inherently unsustainable basic design and mode of operation of society” (Broman & Robèrt, 2017, p. 22). Sustainable development goals help to understand the close interconnections between different problems humanity faces today. According to Broman and Robèrt (2017), a 25-year learning process between scientists and practitioners helped numerous organizations to understand and put themselves strategically towards sustainability. This implies that the UN’s framework helped companies around the world to decrease their negative impact on the environment and the society by embracing innovation, integration of new business models, exploration of new markets, and improving manufacturing efficiency (Broman & Robèrt, 2017). Thus, sustainable development goals constitute a vital framework that helps address the central problems before humanity.

The complexity and versatility of the seventeen goals mentioned by the UN entail the involvement of a large variety of stakeholder groups. While there are two apparent stakeholders, which are businesses and higher education institutions, scholars name many other stakeholder groups. According to Leal Filho and Brandli (2016), stakeholders are “those who have an interest in a particular decision or course of action, either as individuals or as representatives of a group” (p. 336). In simple words, stakeholders are those who have been in any way affected by the issues. Considering the fact that problems mentioned in the UN’s framework affect every creature on the plane in some way, the stakeholders of sustainable development are all the people. In particular, Leal Filho and Brandli (2016) mention universities and other education facilities, financial institutions, government, business, and communities. In other words, sustainable development is highly dependable upon the partnership between the public and private organizations, together with social entities and NGOs (Wojewnik-Filipkowska & Węgrzyn, 2019).

In 2015, the network organization Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data was created, bringing together more than 150 representatives of the business community, government authorities, civil society, international organizations and scientists to collect data on the achievement of the SDGs in the United States (Hoff et al., 2019). In the UK, at the moment, the development of a national sustainable development strategy for the UK, a plan for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda at the inter-ministerial level and the creation of mechanisms for coordinating the policies of individual departments in this direction remain an urgent task for the British government. The UK Stakeholders for Sustainable Development (UKSSD), a multi-stakeholder network that brings together representatives of the public, private, academic and non-profit sectors, is currently developing a national plan for the implementation of the SDGs with the participation of all key stakeholders (Hoff et al., 2019).

In January 2017, the German Federal Government approved a new version of the Strategy for Sustainable Development, which defines specific measures and targets on a wide range of issues related to the SDGs. All government institutions are called upon to contribute to the achievement of specific SDG targets within their areas of competence. Germany’s Sustainable Development Strategy is a measure of the seventeen SDGs at three levels: 1) measures by the German government to achieve the SDGs in Germany; 2) measures with “global implications”; 3) direct support of other countries, carried out in the format of bilateral cooperation (Hoff et al., 2019). In order to inform society about the results of the implementation of the SDGs, the German Federal Government established the Sustainability Forum (‘Nachhaltigkeitsforum’), which is a platform for dialogue between business, society, and political power structures.

In 1999, the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) initiated a special government-business cooperation program “develoPPP.de” as a tool to involve the private sector in promoting international development. Projects carried out on the basis of this platform together with German and European companies are being implemented with the participation of one of three authorized state partners – the financial development institution DEG (Deutsche Investitions – und Entwicklungsgesellschaft mbH), which is a subsidiary of the state development bank KfW (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau), German development agencies (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH) and the international non-profit organization sequa gGmbH, sponsored by the largest German business associations (Hoff et al., 2019).

In 2016, France adopted a strategy called “Let’s Innovate Together,” aimed at adapting concepts of corporate social responsibility to the social and economic challenges articulated in the 2030 Agenda. In order to achieve the SDGs, the French digital platform Agendafrance2030 was launched, which serves as a platform for interaction between various stakeholder groups, creating multi-stakeholder partnerships and disseminating best practices in the field of sustainable development, as well as monitoring progress in this area (Hori et al., 2019).

The participation of NGOs in building sustainable development within and with the participation of communities acquires different forms. Thus, for example, Conservation International is a multicultural organization working since 1987 to protect nature for people (Conservation International, 2020). The company has an extensive network of offices and partners worldwide that helped preserve more than 6 million square kilometers of sea and land across 70 countries (Conservation International, 2020). The organization’s mission is to empower societies to responsibly and sustainably care for nature, biodiversity, and well-being of humanity with a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration (Conservation International, 2020).

Doctors without Borders is an international organization that provides emergency care to people affected by global conflicts, epidemics, disasters, or exclusions since 1971 (Sustainability Degrees, 2014). The company operates under the principles of medical ethics, independence, impartiality, neutrality, accountability, and behavioral commitments to address the threats to human health around the globe (Doctors without Borders, 2020). The members of the organization work under dangerous conditions to life, health, and well-being to help people in need of medical help (Doctors without Borders, 2020).

Greenpeace is one of the most famous non-violent direct-action NGOs, with more than 3 million members. The company values courage and immediate action to help achieve all the seventeen sustainable development goals (Greenpeace, 2018). The organization is known for numerous eco-protests focused on climate change, oceans, forests, toxics, nuclear energy, and sustainable agriculture (Sustainability Degrees, 2014).

WWF is one of the oldest NGOs that started working almost 60 years ago (Sustainability Degrees, 2014). The central effort of the organization is to transform markets and policies toward sustainability and make sure that “the value of nature is reflected in decision-making from a local to a global scale” (WWF, 2020, para. 3). The central focus of the organization is to make a difference in climate, food, forests, freshwater, oceans, and wildlife preservation (WWF, 2020).

Moreover, innovative mechanisms for financing global development in modern conditions are becoming increasingly more in demand. In particular, mixed finance is becoming increasingly important in the international development assistance agenda, which, as defined by the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, involves the strategic use of capital from government or philanthropic sources to attract additional private sector funding required to implement the SDGs (Rhodes et al., 2014). According to estimates, this instrument is capable of attracting additional private capital in the amount of up to 1-1.5 trillion. dollars annually, i.e., the amount of funding required to implement the 2030 Agenda in developing countries (Tietenberg & Lewis, 2019). For the period from 2012 to 2017, the total amount of funds attracted from private sources within the framework of mixed financing mechanisms is estimated at $ 152.1 billion (Tietenberg & Lewis, 2019). Development capital under mixed finance can be provided on both concessional and commercial terms.

Concession capital is provided by specialized government agencies of donor countries (USAID, DFID, JICA, etc.) or private charitable foundations, which can place funds directly into mixed financing instruments or channel them through the participation of intermediaries in the form of multilateral banks development and bilateral financial institutions (Browne, 2017). At the same time, it is emphasized that the management of relationships with stakeholders is carried out not only in order to reduce the negative impact on organizations from disgruntled groups of stakeholders, but also in order to find opportunities to create additional value for different stakeholders (Freeman, 2018).

However, stakeholder identification has been the least studied stakeholder management process for a long period of time. Corporate stakeholder identification methodologies have never been made public. Aubrey Mendelow, in Stakeholder Positioning (1991), proposed the use of a matrix (known as the Mendelow’s Power-interest grid), similar to a SWOT analysis matrix, to classify stakeholders (Harrison et al., 2019). It was planned to position the stakeholders according to two parameters: influence (“power”) and interest, thus dividing them into four groups. One of the main goals of this method was also to rank the stakeholders according to the degree of influence on corporate sustainability. Ronald K. Mitchell, Bradley R. Aigl, and Donna J. Wood (1997), in their article “Towards a Theory of Stakeholder and Identity Identification: Defining Who and What Matters,” set out to complement the original stakeholder theory in terms of environmental governance organizations and contribute to the theory of stakeholder identification according to the “relationship attributes”: (1) power, (2) legitimacy and (3) urgency. Based on the combination of these qualities, a typology of stakeholders was generated, and their characteristics were formulated, as well as their influence on management, strategy, and research implications for the company was shown.

Minu Hemmati, Felix Dodds, Justin Neneity and Ian McHarry (2002) in their work “The Multistakeholder Process from a State and Sustainability Perspective” investigated the phenomenon of multi-stakeholder processes (MSP for short) that come into effect when normal policy no longer works. MSP engages in debate with all those whose interests in the most important social, economic, and environmental issues are at stake. The purpose of the MSP is to find practical ways to continue development. The book serves as a practical guide to organizing MSPs to address complex sustainability issues, including detailed examples of stakeholder management.

Anne Fletcher et al. (2003) describe how NGOs are strategically managed in terms of intangible assets using the Australian Red Cross Blood Donation Service (ARCBS). The purpose of the study was to identify and analyze ARCBS’s external stakeholders. The results include the creation of a “value hierarchy” of 11 stakeholder groups in the organization. These results show similarities and differences between different interest groups in their perception of the key performance area (KPA) of the organization. As a result of the research, ARCBS has received a basis for strategy management and stakeholder engagement. Derek Walker, Linda Margaret Bourne, and Arthur Shelley (2008) look at stakeholder identification from a toolkit and methodological perspective. In particular, the authors pay great attention to the issue of visualization of stakeholder management. In particular, a structure of the ontological positions of stakeholders is proposed, showing “stakeholder value” in space relative to five extremes: radicalism, voluntarism, liberalism, regulation, and analysis.

Stakeholder participation is also recognized as an important factor in the successful implementation of water management plans, particularly when competing decisions or other conflicting demands are made in water-stressed areas. Stakeholder identification allows for greater understanding of the parties involved in water management issues and can also significantly contribute to conflict resolution. An article by a group of Greek scientists (2009) focuses on the development of urban water management plans through stakeholder participation in decision-making in the Cyclades island of Paros (Greece). Since almost all the islands of the Aegean Sea are experiencing a lack of water resources, this topic is very relevant from the point of view of social responsibility. The presented approach focuses on the identification and selection of primary and secondary key stakeholders. The problem analysis was carried out through a problem tree based on the DPSIR framework (Gerasidia et al., 2009). This approach contributed to the development of generally accepted and agreed goals, which led to the identification of alternative water management plans. Public participation was recognized as successful in terms of long-term planning and key recommendations to meet the ever-increasing urban water consumption.

Research by Lisa Edens (2009) focused on identifying key stakeholders for the development of a management plan for Abaco National Park. Using stakeholder mapping, the study identified the current and expected future stakeholders of the park. The results show the diversity of stakeholder groups on the basis of which the priorities for the future development of the park, ecotourism and infrastructure were developed. This research is of practical value and is one of a kind. The method of processing social information for planning subsequent management can, with a little refinement, be applied in many industries.

The widespread use of stakeholder analysis in natural resource management reflects the growing recognition that stakeholders can and should influence environmental policy. Stakeholder analysis is used with the aim of neutralizing conflicts and reducing the marginalization of certain stakeholder groups; it is illustrated using the example of the Peak District National Park in the UK (Leal Filho & Brandli, 2016). The information obtained helps to determine which stakeholders are more important and which are more peripheral, allowing for a study in the area of combining social network analysis with stakeholder analysis.

An article by Guillermo Mendoza and Rabbi Prabhab (2009) describes a multi-pronged value tree approach, created using the value focused thinking method developed by Keeney (1992). This approach allows defining the goals and objectives of stakeholders. The approach is implemented in two stages. Phase I is designed to identify stakeholders and identify a collective “value tree” structured as a hierarchy of goals and objectives, consisting of relationships, connections, and interactions between various alternatives and goals. Hierarchies and networks allow breaking down the complex task of detailed stakeholder assessment, which makes it easier to work and gives a clearer picture of what is happening, without ignoring the relationship of units or assessments of other elements. The second stage allows stakeholders to express their preferences for each item assessed through a voting system, which ultimately leads to data on the importance or relative weights of each item. The study uses the so-called “Analytic Network Process” to process voting results. Findings from a study in Zimbabwe indicated that the proposed approach is easy to implement and can address the questions of whether a particular project can lead to positive change in relationships, and whether the changes that occur are positive for the organization.

Riccardo Gomez, Joyce Liddleb, and Luciana de Oliviera Miranda Gomez (2010) published a study on stakeholder management issues in the public sphere of local government relations in Brazil and England. The authors provided a cross-cultural study of Brazilian and British municipalities using statistical methods. The paper identifies two stakeholder lists for the countries under study in the research and concludes that, despite the cultural differences between Brazil and England, there is a similarity in the methods applied by local government leaders in identifying stakeholders. According to Gomez et al. (2010), the empirical evidence presented in the study supports the hypothesis that stakeholder identification should be viewed as a universal phenomenon. A review of the existing literature has shown that this study is the first of its kind at a cross-cultural level to identify stakeholders.

Thus, the evolution of views on the role of stakeholder management has gone through a long period of formation and subsequent development. The actualization of the problem of stakeholder identification emphasizes the importance of strategic stakeholder management and the introduction of an integrated strategic approach to defining and implementing social responsibility and its distribution among various actors in the framework of sustainable development. As noted above, NGOs represent one of the most controversial categories of stakeholders, and their activities in the context of sustainable development are of particular interest.

The role of NGOs in solving problems of global governance manifests itself in various forms. Today, these structures are actively involved in humanitarian assistance, human rights protection and environmental protection, peace and security, participate in educational programs, sports projects, etc. Namely non-governmental organizations bring the needs of governments and the world community to the attention of and the aspirations of ordinary people, exercise civilian control over the activities of state bodies and promote the active participation of the masses in public and political life at the local and international levels (Islam, 2016). They provide analysis and expertise on a wide variety of issues, including global ones, act as an “early warning” mechanism and help monitor the implementation of international agreements. NGOs traditionally participate in the lawmaking process, including in the field of sustainable development, influencing the position of states, developing draft agreements, which are subsequently submitted for consideration of national governments and intergovernmental organizations.

The need to resolve issues related to the environment on a global scale presupposes the unification of efforts of the international community, the development of international cooperation of actors of different quality. The international importance of global problems requires the search for specific measures to maintain the stability of natural ecological systems. In turn, effective international environmental cooperation is impossible without the active participation of international organizations, both intergovernmental and non-governmental. In the area of rule-making, standardization and global governance, the new role of environmental NGOs in world politics is especially evident. For example, without reliable certification systems for legal diamond mining, like the Kimberley Process certification scheme, which was initiated by activists from the NGO Global Witness and the world’s largest corporation De Beers, which is engaged in the extraction, processing and sale of natural diamonds, it would be, in fact, impossible to block the access of participants in protracted civil conflicts in countries like Sierra Leone and Liberia to their main source of income (Kontinen, 2020). If the World Commission on Dams had not played its mediating mission, the supporters and opponents of the construction of large dams would have continued a fierce struggle, which would not only deplete the resources of both sides, but also lead to an increase in unnecessary costs, and a number of reasonable and necessary projects would be implemented.

The establishment of the International Social and Environmental Accreditation and Labeling (ISEAL) Alliance in 2002 is a good example of the increasingly widespread adoption of the organizational model standard for environmental international NGOs (Lang, 2014). Today, there are twelve organizations in the Alliance. ISEAL has created a Code of Good Practice for Setting Social and Environmental Standards (mandatory for all members since December 2013), which clarifies the general requirements for the preparation, adoption and revision of standards related to social and environmental practice. Through this, a standard organizational model for transnational norm-setting environmental NGOs has been codified.

By placing a strong emphasis on values such as internal community (inclusiveness), openness, responsibility, rationality, and positioning themselves accordingly, environmental NGOs are much closer to the normative ideal of global governance organizations than intergovernmental organizations such as UNEP or FAO. Thus, environmental NGOs not only promote a specific concept of their own identity, but also contribute to the strengthening of a more general model of global governance organizations (Young & Dhanda, 2013).

According to researchers, with whom it is difficult to disagree, at the beginning of the 21st century, NGOs are active in the following areas (Oliveira, 2019):

- Raise issues that are not addressed by government activities;

- Collect, process and disseminate information on international issues that require public attention;

- Initiate concrete approaches to solving such problems and encourage governments to conclude appropriate agreements;

- Lobby governments and interstate structures in order to make the necessary decisions;

- Monitor the activities of governments and interstate structures in various spheres of international life and the fulfillment by states and intergovernmental organizations of their obligations;

- Mobilize public opinion and foster a sense of the “common man’s” involvement in major international problems.

In particular, due to their dynamism, flexibility, close proximity to existing reality, international non-governmental organizations quickly respond to the changing socio-economic and political agenda, not only informing government structures about such changes, but often proposing and using new scientific methods, approaches, options, ways out of the current situations. Acting at the public, professional, scientific and other levels, nongovernmental organizations have the opportunity to study in detail the existing issues and problems and provide assistance where government structures cannot provide it or do not know that assistance is needed. Often, NGOs unite into single “umbrella” structures, federations and transnational networks, which greatly increases the efficiency of their work and enhances their influence on global processes.

NGOs in the field of environmental protection implement many programs, both field and global: together with governments and interstate structures, they initiate the search for approaches to solving environmental problems of mankind, participate in the development and monitoring of the implementation of treaties in the field of environmental protection. Over the past decades, environmental INGOs have participated in the preparation of six major international treaties for the protection of the environment, including the development of the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (2000) (Jelinek, 2006). Environmental international NGOs (INGOs) are actively and sometimes very successfully engaged in lobbying governments, transnational corporations and interstate structures, since one of their main tasks is to put pressure on more influential and powerful actors in the world political system in order to change their environmental policies (Oliveira, 2019). This is a very laborious task, because not all governments and TNCs are ready to follow the instructions of ecologists, sacrificing their own interests for the sake of saving nature. That is why the international NGOs in the field of environmental protection have to come up with new and original ways to achieve such goals.

The most important condition for the full and active participation of INGOs in the processes of global governance is their interaction with national states. These relationships take a variety of forms and are not only businesslike and imbued with the spirit of interaction, but also the relationship between two opponents. For the most part, international non-governmental organizations prefer to cooperate with states, which brings mutual benefit – INGOs receive financial and legal support from the country’s political elite, and the latter uses the capabilities of the third sector, primarily informational, to improve the efficiency of the public administration system. An important function of international non-governmental organizations is their role in establishing links between states and non-state segments. In the international arena, INGOs can act as intermediaries between states or various state structures in solving certain pressing problems. At the same time, sometimes the activities of INGOs turn out to be even more effective than the efforts of the state, since they concentrate all their energy on solving certain specific problems (preserving biodiversity, combating deforestation, promoting education in the field of sustainable development, combating inequality caused by climatic conditions, etc.), which allows, in contrast to states, not to scatter forces, using all their resources in one direction. The so-called personalization of services is exactly what non-governmental organizations are doing in various spheres of social life (Lang, 2014). The richer the choice of services provided by NGOs, and the more complete the information about them, the faster and more efficiently various problems in a particular social segment can be resolved. In addition, to achieve their goals, INGOs operate at two levels at once: local, with the participation of homegrown activists, and international – relying on the support of their own global network structure and world public opinion.

At the same time, due to the extreme heterogeneity, the activities of NGOs, especially of international ones, are sometimes quite contradictory. They often enter into a relationship of competition both among themselves and with government agencies. The autonomous actions of non-governmental organizations have more than once led to the development of conflict situations. In addition, one must not forget that many nongovernmental organizations are undemocratic in their structure, overly bureaucratic; there is a division into a minority of real activists and a passive majority of ordinary members; they do not always fit organically into the system of legislation of the countries where they work, etc.

In addition, the actions of environmentalists, sometimes radical, create a very contradictory reputation for most international environmental non-governmental organizations. Often, nature conservation INGOs are perceived not as real defenders of the environment, but as disturbers of public peace or even as a “fifth column” carrying out someone’s political order. For example, today the number of Greenpeace’s opponents is almost less than its supporters. Among the first ones, there are the Norwegian whalers who have lost their jobs and livelihoods, Canadian lumberjacks, employees of other companies ruined by Greenpeace, public and political figures whose careers were cut short “thanks to” the efforts of the “green,” tribes of hunters-aborigines suffered from global campaigns (Muazu & Abdullahi, 2019).

A typical example of the ingenuity of environmental INGOs is their way of lobbying for TNCs: activists of an environmental organization actively buy up a small number of shares of a large corporation, which is noted to be dismissive of environmental standards. Received amount of 1% of shares allows environmentalists to attend the annual meeting of shareholders and managers of this TNC. Naturally, the meeting turns into a ‘performance by one actor’: using the moment, the INGO activists manage to provide a scandalous resonance, thereby riveting the attention of the world community to a specific problem, for example, against hunting for animals and many others.