Executive Summary

The long-term goal for UK in international trade is to be globally competitive. One major problem is the negative trend in trade deficit during the last decade with EU members. To achieve the best possible outcomes in the short-term and in the long-term for UK, key issues must be resolved between UK and its major trading block, the members of EU. The surplus in UK global service trade is consistently offset by trade deficit in goods. This is consistent with the domestic development of the service sector which dominates more than 75% of UK GDP. Brexit and the “Christmas Eve” agreement are the first few steps in helping UK to be long-term globally competitive in trade. In addition to re-negotiation with EU on better terms in trade, UK needs to seek alternatives in free trade with USA, China, and other emerging countries in Asia. In each negotiation for new trade deals, UK should seek new and better opportunities for trade in services and few selective top trading commodities with higher growth rate including machinery and appliances, and automotive products.

Issues in Trades Between UK and EU Members

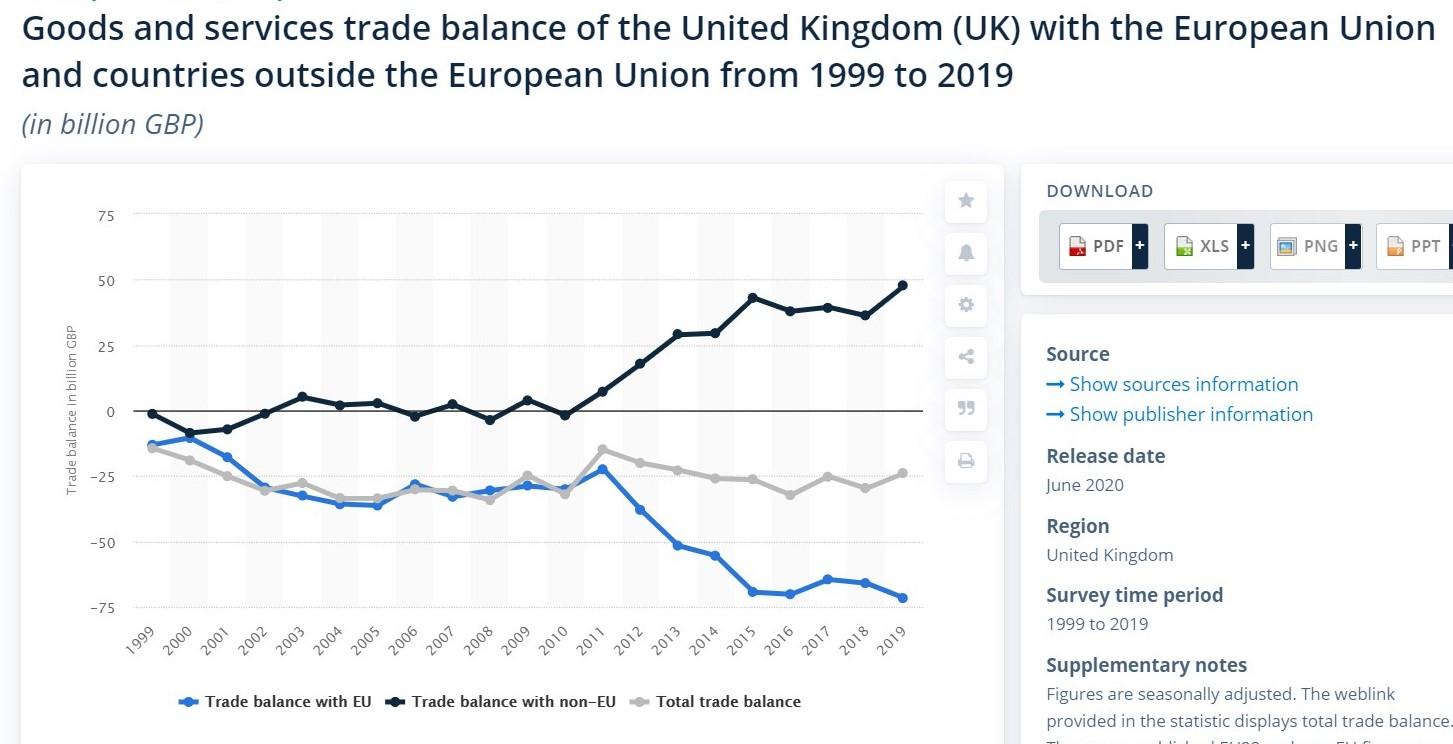

Ever since the formation of the European Union (EU) in 1993, free trade was one of the key goals between the members of the EU including the United Kingdom (UK). However, UK has consistently traded with EU members in deficit between 1999 and 2019 as shown in Figure 1. In fact, the trade deficit for UK with EU members has widen from around £ 25 billion in 2012 to just under £ 80 billion in 2019. During this same period, UK has traded with non-EU countries at near net balance in 2012 to a net surplus of just under £ 50 billion in 2019. These alarming trends led to the initiation of the UK leaving the EU also known as the Brexit. It took UK several years to gather enough domestic support for such a consequential action. By January 2020, the UK government has announced to the world that UK has officially exited the EU. There are many reasons why this move took so long.

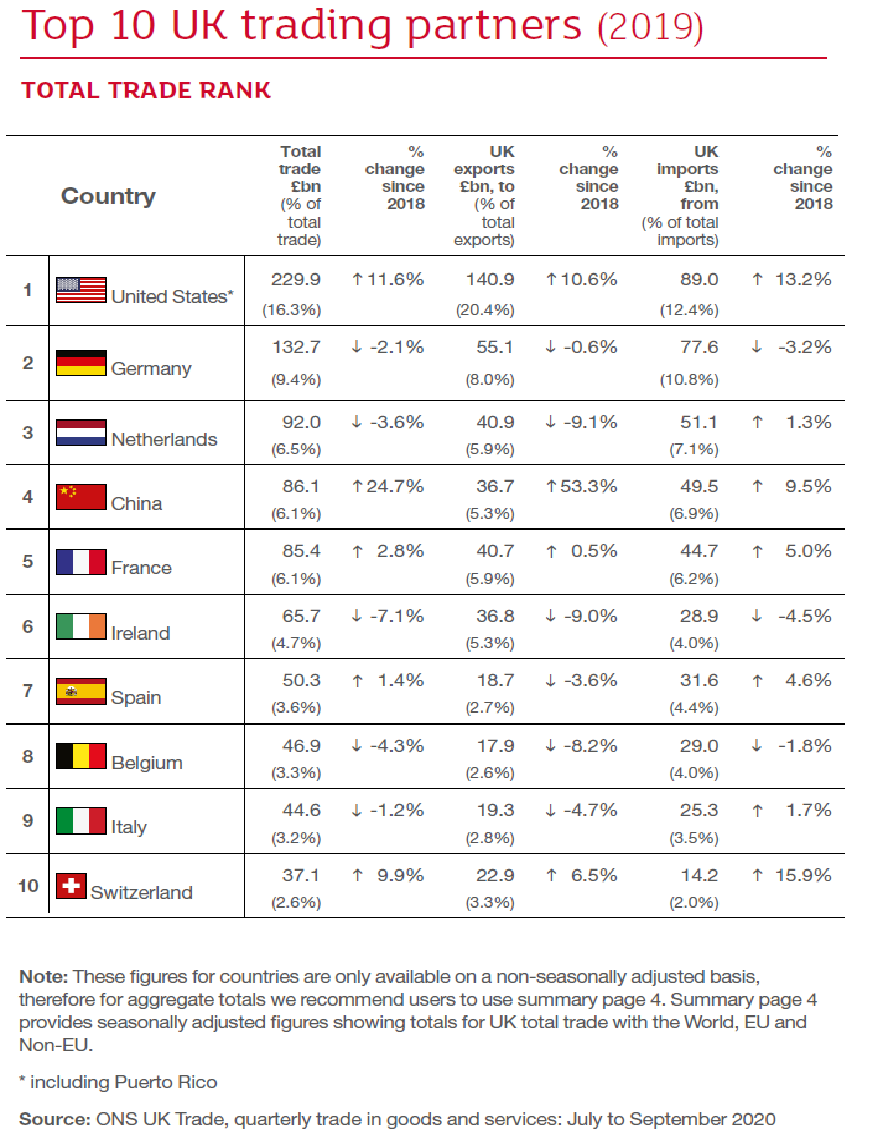

Firstly, EU as a trading block is UK’s biggest trading partner. Exiting EU might potentially cause UK to drop in trade with EU members. As shown in Table 1, eight EU members including four of the top-6 such as Germany, Netherlands, France, and Ireland were ranked among the top-10 trading partners with UK in 2019. United States and China were the only two other top-6 trading partners of UK. Taken as a whole, EU represented UK’s largest trading block. In 2019, there were 43% of the total exports of UK going into the EU members and 52% of the total imports of UK coming from the same trading block. (Ward, 2020) Overall, UK has traded with EU at a deficit of approximately £ 80 billion in 2019. (Ward, 2020)

Secondly, after the Brexit, the downside is that UK might potentially get a significant hit in its services trade surplus with EU. In 2019, UK had a trade surplus with the EU members of just under £ 20 billion in services. On the other hand, the upside is that UK might potentially reduce its trade deficit in goods going forward by reducing UK’s dependence on EU imports.

Finally, the people in UK would fear the potential economic consequences of Brexit if there is a significant drop in UK’s total trade with EU resulting in a reduction in domestic GDP growth and an increase in unemployment. In fact, some of these fears might have become real in 2020 and 2021. UK exports of goods to EU have plunged by 40.7% year over year in January 2021. (The Guardian, 2021)

By the end of 2020, the UK government and the representatives of EU have reached a new EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement also known as the “Christmas Eve” agreement because it was reached on Christmas Eve 2020. This agreement technically would extend beyond a “Free Trade Agreement” (FTA) because there are extra terms within this agreement including the arrangements for security, a set of agreed mechanisms for the resolution of disputes and enforcement. The free trade part of the agreement would allow both UK and EU members to trade without tariffs and quotas on goods. (Amar, 2021) However, this agreement would allow for the possibilities for additional cost for businesses of trading from both sides such as transport and customs costs. In addition, there were provisions for trade other than for goods, including services and investment. The agreement included obligations which would ensure 1) fair market access; 2) fair national treatment; 3) local presence barriers; and 4) mutual recognition of professional qualifications. (Amar, 2021)

On paper, the “Christmas Eve” agreement sounded great for both UK and the EU members. However, there are many hidden potential trade barriers that can form. For examples, UK professionals in the financial or other service sectors might have to obtain EU member local certifications, special visas, or licenses before they can “export” their professional services. Other possible issues with trade would be customs clearance, health and safety inspections, and registrations for local taxes such as the VAT in UK for goods being traded. (Amar, 2021) All these hidden trade barriers would potentially slow down trades, increase the cost of trades, or both. Given the recent political agenda of UK and of EU members, foreseeable difficulties might develop in making trade of goods and services more expensive or more difficult. In fact, there might be signs for this happening in 2020 and in the first quarter of 2021. In 2020, the UK total exports to EU have dropped by over 17%, the total imports from EU have also dropped by almost 19%, the total trade of goods with EU has dropped by almost 16%, and the total service trade with EU has dropped by almost 22% from 2019. (UK Department of International Trade, 2021) However, such drop in international trade for UK could be explained by the drastic changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and even in first quarter of 2021. Therefore, at best, the future trade between UK and EU members will be filled with uncertainties.

Analysis of the Trends in UK International Trade

Since there was the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, international trade data would be skewed due to shutdowns and other economic issues relate to the pandemic. Therefore, the analysis of UK international trade should be done for period leading up to 2019. As shown in Table 2, in 2019, the total exports of goods and service of UK was just under £ 690 billion, and the total imports was just under £ 720 billion. Out of which there was a trade surplus of over £ 100 billion in service. On the other hand, there was a trade deficit of just over £ 130 billion in goods. (UK Department of International Trade, 2021) The trade deficit of goods was greater than the trade surplus of services for UK such that the overall trade was netting out with a deficit of just under £ 30 billion in 2019.

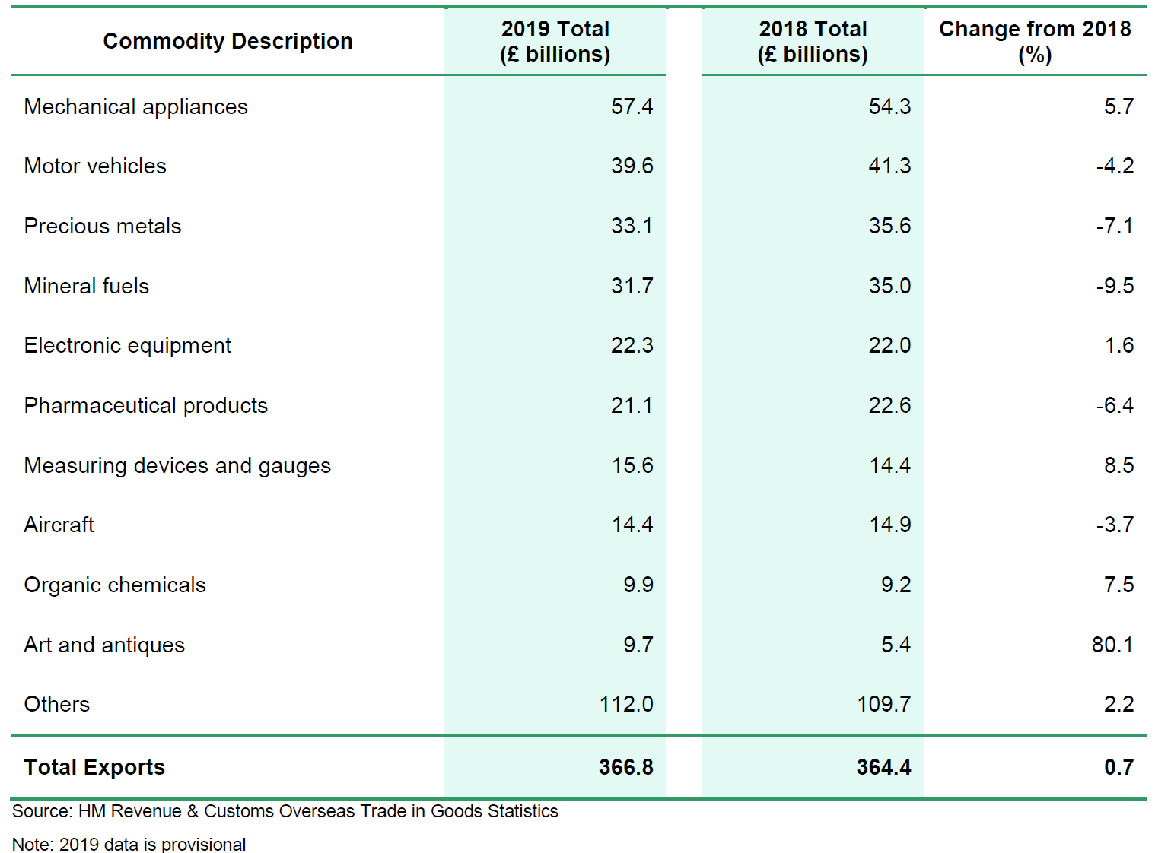

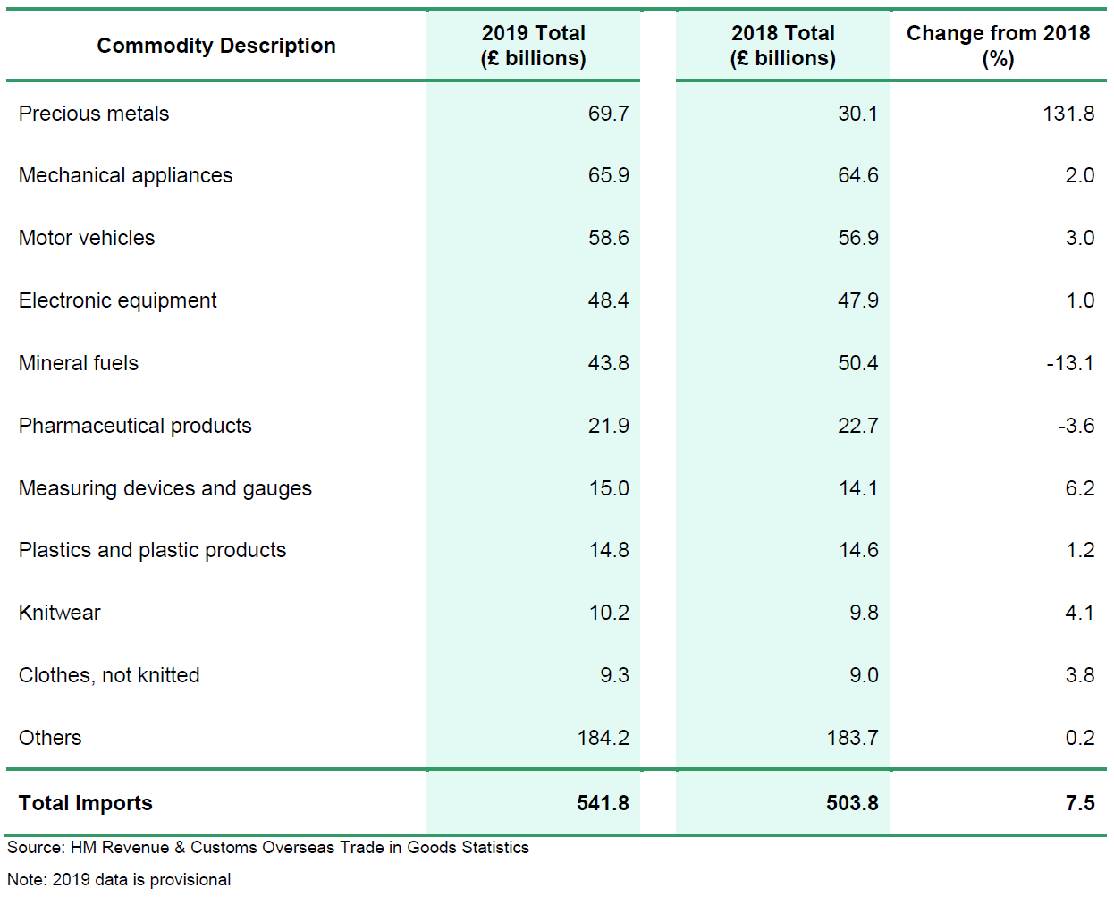

As shown in Table 3, the top-5 exporting commodities included mechanical appliances, motor vehicles, precious metals, mineral fuels, and pharmaceuticals for UK in 2019. UK’s top-10 exporting commodities accounted for over 53% of all exports. As shown in Table 4, the top-5 importing commodities for UK in 2019 were the same as those of top-5 exporting commodities. UK’s top-10 importing commodities, however, accounted for over 70% of all imports. Together the difference in the top-10 importing of goods and the top-10 exporting of goods has resulted a trade deficit of just under £ 170 billion in 2019 for UK.

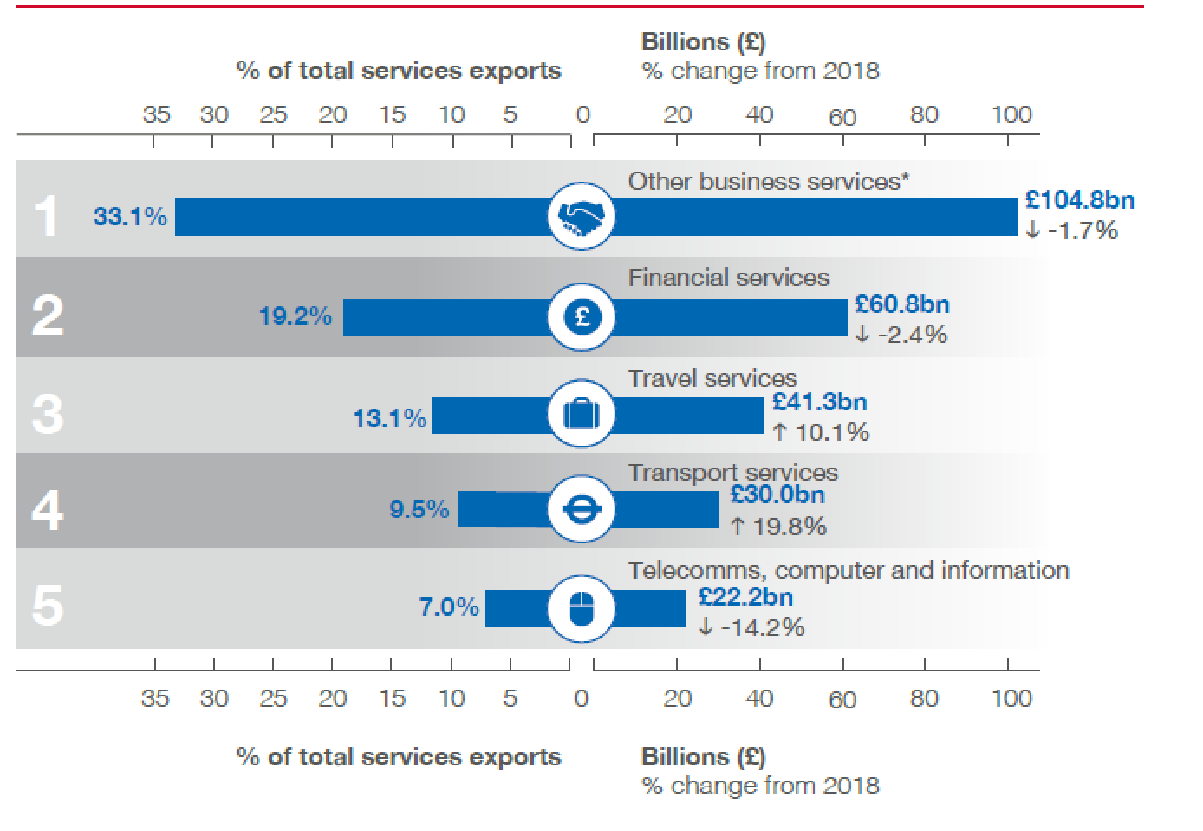

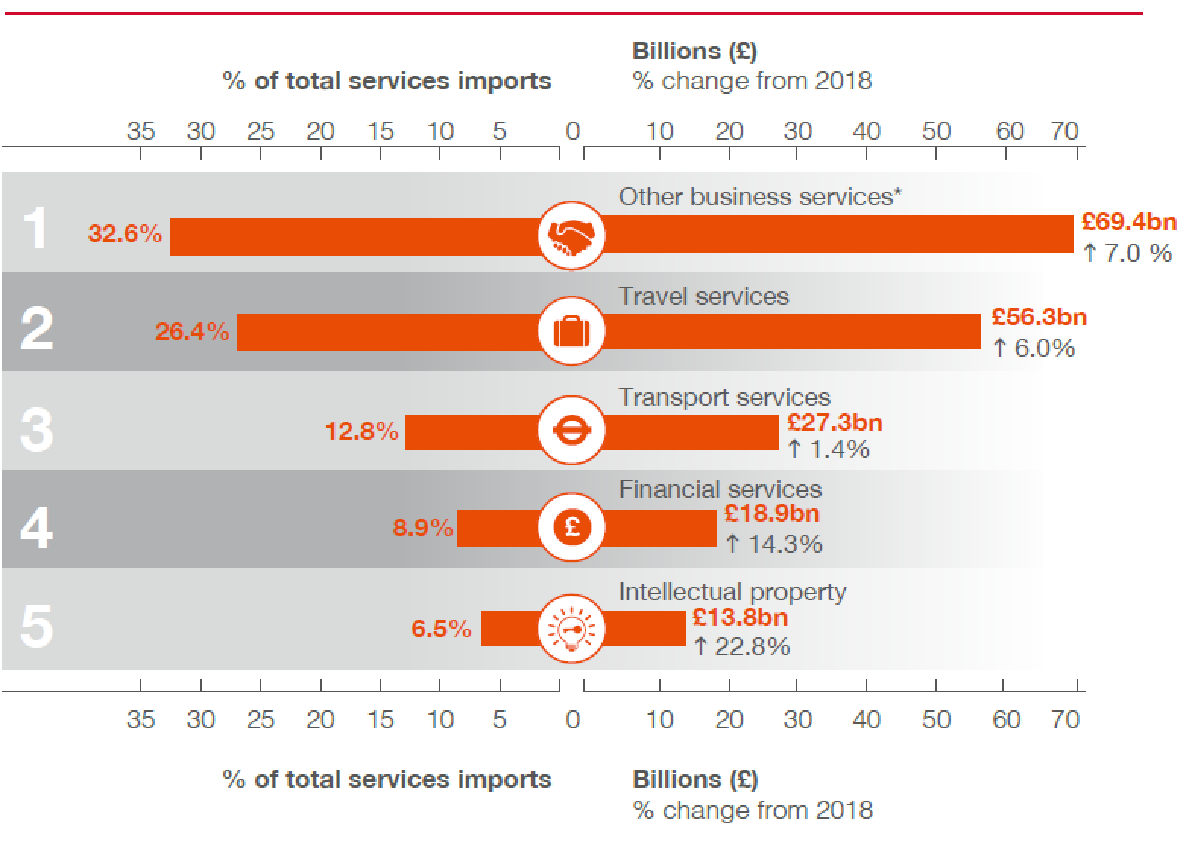

In terms of services trade in 2019, as shown in Figure 2, UK top-5 services exports included other business services, financial services, travel services, transport services, and services related to telecommunication, computer, and information. Together these top-5 services exports accounted for almost 46% of all exports in 2019 for UK. As shown in Figure 3, UK top-5 services imports accounted for only 30% of total imports for UK in 2019. UK’s services trade surplus came mainly from other business services and financial services. The trade surplus in services was just over £ 100 billion in 2019 for UK.

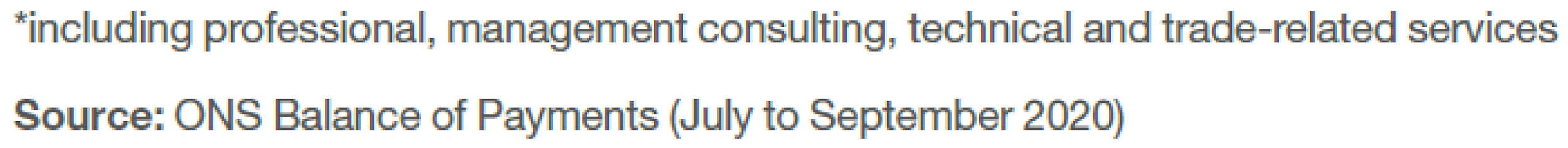

As shown in Figure 4, UK services exports, excluding travel, transport, and banking, have grown at approximately 10 % per year between 2001 and 2018. On the same period, UK services imports, excluding travel, transport, and banking, have only grown at approximately 8% per year. In 2018, the UK services (excluding travel, transport, and banking) trade surplus was approximately £ 90 billion. When combining data from Figures 2 and 3, over 85% of the UK services trade surplus in 2018 came from business services including management consulting, financial services, and computer and information system services. In the same year, over 82% of this same trade surplus came from trade with non-EU members based on data in Figures 2 and 3 along with data previously mentioned. (Ward, 2020) According to the UK Office for National Statistics, the services sector is the largest sector in UK accounted for more than 75% of UK GDP in 2019. Manufacturing and production only accounted for less than 21% of UK GDP and agriculture accounted for less than 0.6% of UK GDP. Having healthy growth in trade surplus in the services sector would boot the UK economy. (Page, 2020)

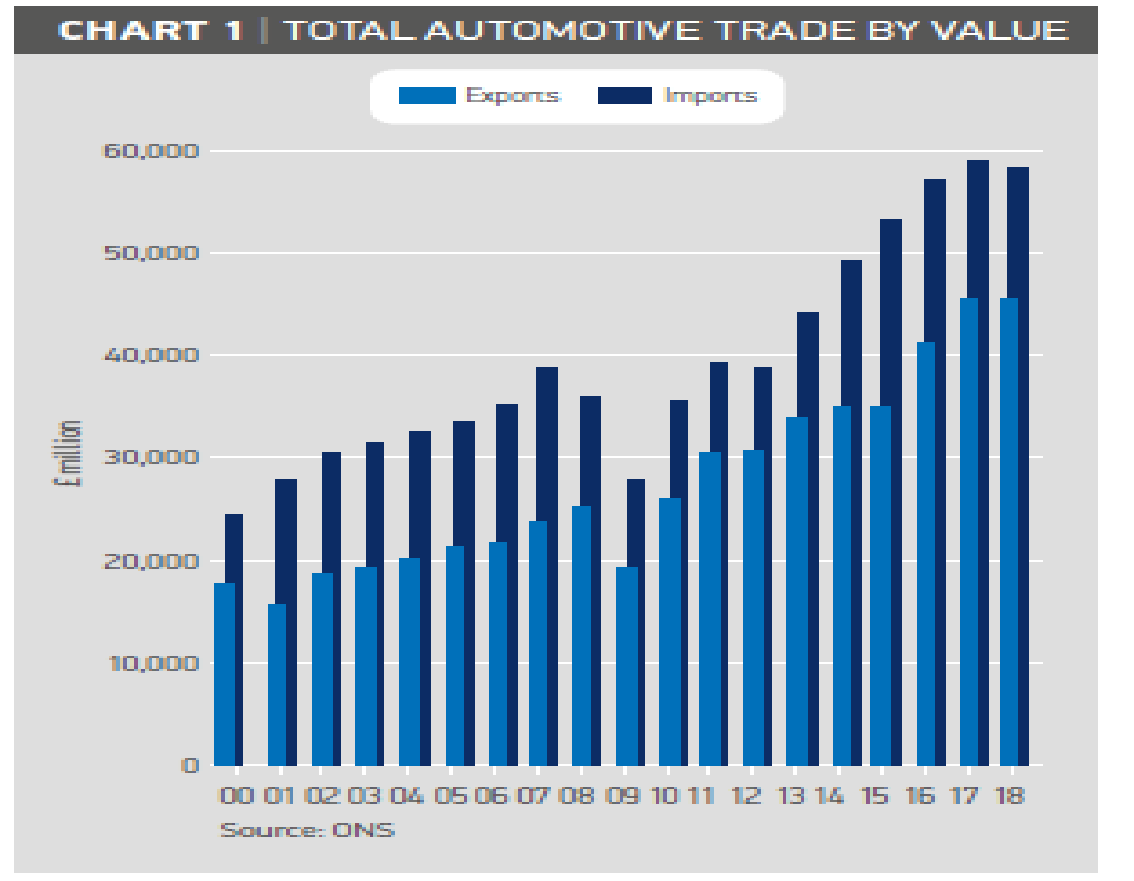

In recent years, UK has consistently traded with deficit in goods. However, UK’s top commodity trade is in the machinery and appliance sector. In 2019, the total exports in this sector have reached just under £ 60 billion with 5.7% growth from 2018 as shown in Table 3. The total imports of machinery and appliance sector in 2019 was just over £ 65 billion with a modest growth of only 2% from 2018 as shown in Table 4. The second largest UK trade in goods is the automotive sector. Automotive exports have almost reached £ 40 billion with an average growth rate of total automotive exports for UK between 2009 and 2018 at approximately 10 % as shown in Figure 5. On the other hand, the average growth rate of total automotive imports for UK in the same period was just under 9%. Unfortunately, both the imports and exports of the automotive sector have reached a plateau during the last three years. In fact, in 2019, both UK imports and exports of automotive products were slightly down from previous year.

Based on the previous analysis of UK’s current trends in international trade, it is possible for UK to reduce trade deficit in goods or improve trade surplus in services if UK would make new trade agreements with USA, China, and other Asian countries. In addition, UK needs to re-negotiate with EU to make modifications on the “Christmas Eve” agreement by focusing on trade in services and the top trading commodities.

Alternatives for Improving UK Global Competitiveness in Trade After Brexit

Ultimately, the key reason why UK wanted to leave the EU was the consistent widening of trade deficits with EU as a trading block. Such a trend would cause UK domestic economy to decline in the long run. This long-term decline would lead UK economy to have lower GDP growth and higher unemployment – UK certainly would not want this. Therefore, it is imperative for UK to seek alternatives to improve its global competitiveness in trade. Brexit should only be considered as the first step in this process.

The “Christmas Eve” trade agreement only allows UK and EU members to resume some levels of trade. UK should view such an agreement as the starting point for further negotiation. As mentioned earlier, both UK and EU members have experienced a significant drop in trade in 2020. Perhaps this is related to the pandemic in 2020. However, recent news describing the relationship between the UK government and the EU representatives have revealed major differences in political agenda among them. (Surin, March 2021) The outlook for improving trade between UK an EU members in the future is poor. Worse yet, the volume of trade with EU members might even continue to slide downward in the long run if UK did not handle the negotiation correctly.

It appears that UK has been diversifying its trade with non-EU members during the last two decades. The share of UK exports into EU has fallen from 54% in 2002 to 43% in 2019. Other the other hand, the share of UK imports from EU fell from 57% in 2006 to 52% in 2019. (Ward, 2020) In addition, the UK trade with USA and China was significant during the last few years such that USA and China were ranked first and fourth as trading partners of UK in 2019 as shown in Table 1. Both countries were trading with UK in an increasing trend in exports and imports during the last decade as shown in Table 5 and Table 6. The ability to negotiate favorable free trade agreements (FTA’s) with both USA and China for UK would determine if UK would be globally competitive in trade in the coming decade.

The first option of new trade deals for UK outside of the agreement with EU should be the U.S.A. since the U.S.A., by itself, is the biggest trading country with UK and second biggest trading block if all the EU trading members with UK are considered as one unit.

USA was the most significant trading partner of UK, ranked first in 2019. UK exports of goods to USA has increased from £ 30.4 billion in 2009 to £ 51.6 billion in 2018, about 2.3% annualized growth rate as shown in Table 5. UK imports of goods from USA has increased from £ 23.4 billion in 2009 to £ 39.1 billion in 2018, at about the same 2.3% annualized growth rate. In terms of services trade with the USA, UK total services exports has increased from £ 32.8 billion in 2009 to £ 75.5 billion in 2018 at about 4.2% annualized growth rate. In the same period, UK has increased importing services from the USA from £ 20.8 billion in 2009 to £ 37.4 billion in 2018, at about 3.3% annualized growth rate.

With significant trade surplus in services and moderate trade surplus in goods with USA in recent years, UK should focus on establishing a new trade agreement with the USA going forward. Particularly, UK should focus on specific exporting goods to USA such as machinery, automotive and pharmaceutical products and all of UK exporting services to USA in the new agreement. If possible, UK should seek higher level of trade with USA. This would potentially make up the potential decrease in trade with EU members. Any increase in trade with the USA would most likely net out a surplus on goods or services for UK.

In terms of new trade deal with the USA, in October 2018, then President Trump has initiated a negotiation on this with UK government. By May 2020, the negotiations between UK and USA were formalized. Representatives from both sides held four sets of negotiating sessions in May, June, July/August, and September in 2020. In December 2020, trade agreements were entered into force by an exchange of letters between the USA and the UK governments. (The Office of the Unites States Trade Representative, 2021) During the trade negotiation, several key issues were raised (Trade Justice Moment, 2021): 1) health standards – particularly UK were more concern about consumer exposure to health risks in foods that would be imported from the USA; 2) environmental standards – the UK will have to choose which regulatory system it wants to align with; 3) investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) allows foreign investors to sue governments for certain kinds of measures which harm their profits; 4) public services – an UK-US deal is very likely to include public services provisions; 5) regulatory cooperation – a key aspect of TTIP was ‘regulatory cooperation’, where European and American regulators would work together to review and seek harmonization on regulations in the EU and the United States; 6) trade democracy – the participation of the general public in the finalizing the trade deal is key to buy-in and support; and 7) restrictiveness of a US trade deal – since there was a change in the office of president of the USA, geopolitical alignment must be established between the USA and UK government to ensure general support from both sides. Biden’s administration would have a different agenda when it deals with the negotiation with the UK government on this new trade agreement. Whenever the new trade deal with the USA would be finalized, UK would come out a winner regardless of the future of the trade with EU members.

Having a new trade deal with the USA might not be enough. The needs of UK international trade because of the potential slowdown in trade with EU members might require UK to seek trade agreement other than with USA. The second option of new trade deals is a new free trade agreement with China. Although China was less significant in terms of trade with UK comparing to the EU trading block or to the USA, UK trade with China has risen in recent years such that China is ranked fourth in the top-10 trading partner list in 2019 as shown in Table 1.

Since 2009, UK exports of goods to China has increased from over £ 5 billion to just less than £ 21 billion in 2018, at about 5.2% annualized growth rate as shown in Table 6. On the other hand, UK imports of goods from China has also increased from just over £ 25 billion in 2009 to just under £ 43 billion in 2018, at about 2.2% annualized growth rate. In terms of services trade, UK services exports to China have increased from £ 1.9 billion in 2009 to £ 4.5 billion in 2018, at about 4.1% annualized growth rate. UK services imports from China have also increase, but at more modest rate of 3.3% from £ 1.3 billions in 2009 to £ 2.1 billion in 2018.

The potential trade deal should center around UK imports of goods from China and specific items of UK exports of goods and services to China. In terms of imports from China, UK should consider better pricing or qualities of goods comparing to those from EU members. That way, UK would have alternatives in case the trade with EU members continue to diminish. In terms of exports, UK should seek new opportunities in services trades, and UK top exporting commodities such as appliances and automotive products.

In fact, in 2020, the British Chamber of Commerce in China (BCCC) has called the UK government to prioritize trade negotiations with China for a bilateral free trade agreement. In that initiative, China was looking for complementary roles in the trade with UK. (Bhaya, 2020) According to this publication, UK should take a more balance approach in the trade agreement with China in which UK should not be swayed by external political pressure, but UK should look for support in critical growth areas as well as creating new trade opportunities.

Given the recent negative interactions due to human right issues in China, the ties between the UK and China have been increasingly antagonistic in recent years. The UK government has publicly condemned China’s erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomy. In late 2020, the UK also banned the Chinese Huawei telecom giant from involvement in its domestic telecommunication business. Going forward, UK-China political relation would have a huge impact on how they might settle into a free trade agreement. Whether the trade talks would result in positive impact on UK’s long-term global competitiveness would remain uncertain due to current political differences with China.

The third option for UK is to explore other trade deals with some of the emerging countries in Asia including those that are parts of the top-20 trading partners of UK in 2019 such as Japan, India, Singapore, and South Korea. The main goal for UK in developing these new trading agreements is to supplement what UK cannot do with USA, and China. UK should seek better pricing in importing goods and better opportunities for UK exporting goods and services assuming the volume of trade with EU members would continue to decrease in the future.

The fourth option for UK is to seek to re-negotiate better trade terms with EU members such that UK services exports would not be too restrictive. UK should seek “grandfather” rules for existing trade of services. There is no reason for extra trade barriers for such business activities since UK service sector personnel are more familiar with doing business at the local level in EU member countries. If possible, UK should negotiate the elimination of local licensing, certification and visas requirement for existing businesses that were conducting exports of services to EU member countries. To slow down the decreasing trend in trade of goods, UK also should negotiate for the reduction in the needs for customs clearance, health and safety inspections and other restrictions if goods were traded prior to Brexit. UK should also seek exemption of local taxes since these goods were traded without these extra tax burdens prior to 2020.

Obviously, the re-negotiation of trade agreement with EU would not be an easy task. But it is important enough that the UK government should consider if they want to slow down the negative trend in trade with EU, particularly in the services sectors.

Summary of key recommendations to UK and Conclusion

Table 2. UK 2019 International Trade Summary. (UK Department of International Trade, 2021).

*including professional, management consulting, technical and trade-related services.

Source: ONS Balance of Payments (July to September 2020)

Table 5. UK Trade with the USA from 2009 to 2018. Source: UK Office of National Statistics.

Table 6. UK Trade with China from 2009 to 2018. Source: UK Office of National Statistics (2009 to 215 data).

Bibliographies

Ward, Matthew “Statistics on UK-EU Trade” 2020 House of Commons Library.

Statistics on UK-EU trade – House of Commons Library (parliament.uk).

The Guardian “The Observer View on the Grim Effects of Brexit Being Impossible to Hide” March 14, 2021 The Observer view on the grim effects of Brexit being impossible to hide | Brexit | The Guardian.

UK Department of International Trade “UK Trade In Numbers” February 2021, UK Trade in Numbers Pocketbook 2021 (publishing.service.gov.uk).

Ali, Amar “We Have a Deal! What Is Included In the New EU-UK Trade And Cooperation Agreement?” 2021 Brexit Deal: The Overview Of The New EU-UK Trade And Cooperation Agreement.

Page, Vennessa “The Economy of United Kingdom” 2020 How the UK Makes Money.

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders “2019 UK Automotive Trade Report”.

Surin, Kenneth “The EU-UK Phony War on Vaccine”.

The EU-UK Phony War on Vaccines – CounterPunch.org.

UK Office of National Statistics – downloaded excel files containing data on UK imports and exports by countries and by categories (1997 to 2019).

The Office of the United Stated Trade Representative “US-UK Trade Agreement Negotiations” January 2021 U.S.-UK Trade Agreement Negotiations | United States Trade Representative (ustr.gov).

Trade Justice Moment “UK-US Trade Deal” access April 1, 2021 UK-US trade deal | Trade Justice Movement (tjm.org.uk).

Bhaya, Abhishek A. “British Chamber of Commerce calls for China-UK free trade deal amid COVID-19, Brexit worries” 2020 British Chamber calls for China-UK free trade deal – CGTN.