Introduction

In the scant ten decades since employee relations evolved from productivity-increasing ‘time and motion’ studies to ‘strategic HR’, the role of human relations practitioners has changed many times. Welfare management came and went. This was followed by administration, negotiation with newly-assertive unions, legal compliance and organisational development, all roles that still ‘play out’ with varying emphasis and in differing contexts.

This paper examines two theoretical models of the HR role, assesses the empirical evidence offered in support and examines applicability to a small business of which the writer is part.

Selected Models

We take consideration, first of all, of models propounded by Ulrich (1998) and Storey (1992).

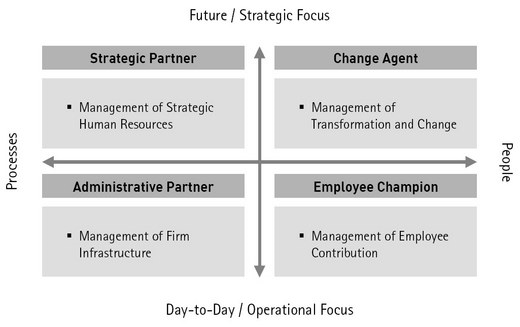

Ulrich reduces the tremendous complexity of the HR function (Caldwell, 2003, p. 988) to four roles (see Figure 1 alongside) that underlie the bid to become a ‘strategic partner’ of the firm. While acknowledging that HRD must, after all, protect employee welfare, Ulrich constructs the strategic contribution around aligning employee skills and contribution with company goals. Then motivating employees to work towards corporate goals becomes the logical next step, a natural outgrowth of the great body of work that has been done in the area of motivation theory.

The four roles in the Ulrich construct correspond to distinct activities and deliverables. Thus, the first metaphor of ‘strategic partner’ embodies the role of managing strategic resources (in this case, employee skills and teamwork), focuses on the activity of aligning HR with business strategy, and mandates a deliverable in the form of executing strategy. The second metaphor of ‘administrative expert’ is associated with the role of managing company infrastructure, activity in the areas of re-engineering processes and hence, a deliverable in the form of building efficient infrastructure.

Thirdly, the metaphor of ‘employee champion’ mandates the role of managing transformation and change. In Ulrich’s view, this is achieved mainly by listening and responding to employees in order to attain the deliverable of enhancing staff commitment and capability. Since this alone will not accomplish smooth change management, the fourth metaphor/role is needed: ‘change agent.’ Here, Ulrich would have HR see to the activity of managing transformation and change towards the goal of creating renewed infrastructure.

Viewed in another light, HR roles under this construct break out into three levels. HR impacts organisational capabilities in the three roles of ‘talent manager’, ‘strategy partner’, and ‘culture and change steward’. Being a business planning executor and, more critically, ‘business ally’ affects systems and processes. Finally, it is in the area of relationships, at the intersection of people and business concerns, where HR must undertake the role of ‘credible activist’. All these may be attained not by hiring multi-talented individuals but by ensuring that a comprehensive HR process and service portfolio is within the remit of the entire HR organization.

Ulrich supported the implications of his theoretical model with empirical proof in the form of case studies. One educational (and easily-implementable) example was the case of HR at Sears undertaking to enhance company culture and, along the way, volunteering to make the business case for doing so. The result was hard data demonstrating that even slight improvements in employee commitment fostered tangibly better customer commitment and store profitability. This is an excellent example of marketing a role and goal of transformation that positively impacted employees, customers, and Sears stockholders.

In turn, the Storey model positions key roles along the strategic-tactical and “interventionary”/not dimensions. The former corresponds to Ulrich’s opposing poles of “future/strategic” and “operational/day-to-day” concerns.

One must perhaps quibble with Storey’s “non-interventionist” pole. There is surely nothing passive with ‘Advisors’ acting as facilitators and internal consultants merely ‘offering expertise and advice to line management’ (Storey, 1992, p. 171). This can be likened to the difference between consensus building and dictating decisions from the top. Both processes are goal-oriented anyway.

In contrast, the ‘handmaiden’ role merely reacts to, and dispenses services at the initiative of line managers. ‘Regulators’ seem to embody the old, much-maligned roles of ‘policy police’, labour negotiators, and union breakers.

Most admired in the Storey paradigm, presumably, are the ‘changemakers’ who keep to a strategic agenda around business performance goals while relying on managing employee commitment and motivation to achieve this.

Assessing the two constructs side by side, Caldwell (988) remarked how the passing of a decade had tended to cast Ulrich’s model as a prescriptive ideal towards which to strive while the Storey theory seemed more amenable to empirical testing. In addition, a 1999 survey of 98 HR/personnel manager respondents from among leading UK companies suggested that: a) the four roles posited by Storey are not mutually exclusive but coexist as ‘major’ or ‘minor’ roles; 2) the continued evolution and complexity of organizational form challenge HR to evolve new roles and identities; 3) even as HR managers insist they cope very well with ‘role ambiguity and conflict’ (Ibid.)

The Roles of HRD in Practice

Being more appreciative now of the total value an HR organisation can provide a firm, we come to the pragmatic question of whether they apply to a two-person HR organisation within an SME and cast in the role of Ulrich’s ‘Administrative Expert’. What lessons do these models provide for surmounting inexperience and aspiring to become strategic as the unit expands in future?

The lesson one draws from the ‘Business Partner’ concept is to avoid being pigeonholed in an administrative role and to take the initiative to broaden the remit of the unit today, not five or ten years down the road when more staff are available. As the business grows, otherwise, the line managers who are the ’customers’ of HR simply become accustomed to an HR organisation of form-fillers and administrative assistants, nothing more.

Reinhardt (2008) suggests pro-actively operationalising the Ulrich model at once by taking three steps:

- Save time, cost and break ties with exclusive identification as administrative service by switching to a Shared Service Centre facility, i.e., outsourcing. Outsourced HR takes on the responsibility for all routine processes: contract management, payroll processing and pay slips, and training seminar administration. Resistance to undertaking this may spring from the perception that administrative tasks are too specialised for outsiders to understand but the truth is that these are all functions with a great degree of commonality across industries and irrespective of the scale of company operations. Nonetheless, it is incumbent on my HR organisation to implement proper oversight for professionalism and quality service.

- Immediately transition to a proactive ‘customer management’ role by establishing or deepening relationships with the line managers and supervisors who are HR partner in employee relations and motivation.

- Break new ground with initiatives, however rudimentary, to systematise employee development, performance appraisal, job evaluation and salary grade structures. Classed as Principles and Concept Development (Ibid.), such a role can propel HR marketing by offering management development as the inducement.

Conclusion

Models being what they are, both the Ulrich and Storey theories succeed in postulating key roles for the HR organisation in a sizeable company, notably one where managing the people resource is complicated by globe-spanning operations. Neither model fully accounts for the rich tapestry of HR functions that advance employee well-being in tandem with corporate goals. Neither do they seem to cover the limitations of flexing HR potential in an SME. Nevertheless the astute HR manager must learn to define her role in broader, more diverse terms and market the same to her internal stakeholders: the CEO, managers and senior supervisors.

Bibliography

Caldwell, R. (2003)The changing roles of personnel managers: Old ambiguities, new uncertainties. Journal of Management Studies, 40: pp. 983-1003.

Reinhardt, A. (2008) Barriers and open doors with “HR Business Partners”: An HR concept is translated into practice. Steinbeis Publications. Web.

Sissons, K. & Storey, J. (2000) The realities of human resource management: Managing the employment relationship. OUP

Ulrich, D. (1998) A new mandate for human resources: Analysis of the functions of the human resources departments in increasing productivity and profits. Harvard Business Review, 76 (1) pp. 124-134.