Outline

Balancing the need for revenue in Lhasa by increasing attractions sites for visitors may not only lead to potential damage to the sites but is likely to conflict with the social norms and traditions. Lhasa, the regional capital of Tibet is located on the north Shore of Lhasa River with a population of 550, 000 people. The Tibetans are the majority (87%) of the total population (Liang, 2008). As a world-level tourism destination, the region is also an economic, political and cultural or religious (religious centre of Lamaism) centre of Tibet region (Sofield & Li, 2007). This research was based on a review of secondary materials and resources. Published books, newspaper, and journal articles were widely utilized. Web-based resources were also used. The results showed that the local community does not get enough benefits from the tourism revenue as they are supposed to, with the activities from tourism threatening to destabilize their rich indigenous culture of Buddhism. It is therefore proposed that an integrated approach of development should be taken into consideration to ensure full participation of the community in this sector for sustainability.

Introduction

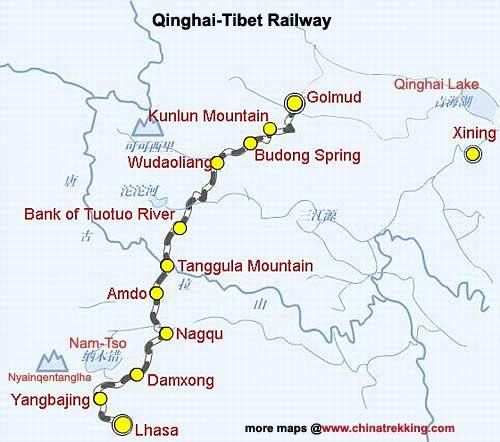

China wants to be the number one tourist destination in the World and of the 812 World Heritage sites, China is listed to have 30 sites slightly behind Italy and Spain, but Beijing is reputed to want 100 more (Wunder, 2000). It is estimated that revenue from tourism can increase 25-fold after World Heritage listing, a figure extrapolated from the results of listing of walled City of Pingyao in Shanxi province, with an estimated income of $2 billion annually (Yamamura, 2004; Wunder, 2000). It is no doubt the government has invested heavily in the development of infrastructure to boost tourism, considering the potentiality of the tourism sector. For example, it is far from uncommon to notice major buildings in Lhasa that had been destroyed being rebuilt, applying cosmetic facings in this historic area to create more authenticity when it was noted that they could attract more visitors (Yeh, 2004). The Chinese government has also spent $4.2 billion on the construction of a train route in to Lhasa (1956 km long Qinghai-Tibet Railway) (Wild, Cooper & Lockwood, 1994). These developments began in the 1980s, where Lhasa, known in some quarters as ‘place of god’ began to revive its position not only as the major pilgrimage site for Tibetan Buddhists, but also as an alluring tourist destination for both international and domestic tourists (Cochrane, 2007).

Even though the proponents of the tourism development argue that it will help the Tibet’s economy, including doubling its annual revenue from tourism to $725 million by 2010, critics, however, are concerned with the environmental damage and the impact it will have on the historical culture of Tibet (Telfer & Sharpley, 2007). The application of socialism and the conservation of tradition are in contrast to the demands of the development in Lhasa, therefore threatening the stability of the region as seen in the recent series of protests in this culturally rich region of the country. If how community and individuals react to outside forces is an indication of the strength of the host culture, then the people of Tibet have high regard to their culture.

The difficult act of balancing the need for revenue in Lhasa by increasing attractions sites for visitors may not only lead to potential damage to the sites but is likely to conflict with the social norms and traditions. Is there a resilient local culture in Lhasa, Tibet or is there possibility of it being overrun by the culture of tourists and the rapidly developing global information network? Considering the inherent dilemma in the modern tourism development that if a culture is frozen in time to be put on display for tourists, can there still be development? It may be observed that cultural brokers will definitely seek to make profits while others will try to avoid the tourists. This paper analyses the development of tourism and the socio-cultural conflicts between local residents and mass tourism development in Lhasa after the redevelopment of Qinghai-Tibet Railway.

Aims and Objectives/Methods

The objective of this research was to understanding the socio-cultural conflicts between local residents and mass tourism development in Lhasa after the redevelopment of Qinghai-Tibet Railway.

Main aims and objectives achieved from this research are:

- Explanation of the reasons for mass tourism development in Lhasa

- Identification of the negative socio-cultural impacts which have been caused by development of mass tourism in Lhasa.

- Outlining of some recommendations and solutions for improving or minimizing the negative socio-cultural impacts.

Research Questions

The research questions answered are:

- What kinds of roles do the mass tourists play in the Lhasa?

- Are there any connections between socio-cultural conflicts and environmental issues at the destination?

- What are the responses from local residents when they meet tourists?

Methodology

This research was based on a review of secondary materials and resources. Published books, newspaper, and journal articles were widely utilized. Static information such as the number of visitor in Lhasa 2007 was retrieved through web-based research and electronic resources. Due to the distance between New Zealand and Tibet, web-based research played an important role in this research. Search terms were used to narrow down on the specific area of interest: Tourism and socio-cultural conflict in Tibet. Therefore the terms used in the search were: “culture in Tibet”, “Tourism in Lhasa”, “Conflict between Tourism development and Culture in Lhasa”, and “Tourism and ecosystem”. Google search engine was mainly used in this case and only relevant and authentic materials were selected for use, i.e. peer-reviewed journals, e-books and articles with recognized publishers like Sciencedirect and Wiley.

Case Study Characteristics

With 1300 years of history, Lhasa, the regional capital of Tibet is located on the north Shore of Lhasa River and is over 3650 meters above the sea level (Liang, 2008). Its 550, 000 people is predominantly Tibetans, who account for 87% of the total population (Liang, 2008). Other than being well-known as a world-level tourism destination, Lhasa is also an economic, political and cultural or religious (religious centre of Lamaism) centre of Tibet region (Sofield & Li, 2007). The establishment of the Department of Tibetan Tourism Development in 1979 and the completion of Qinghai-Tibet Railway in 2007 have seen significant growth of the tourism industry in Lhasa from 1980, that is, there were an approximated 7,330,000 number of tourists who visited Lhasa (Liang, 2008; Sofield & Li, 2007). Of all the visits, 1,436,000 were international tourists while 5,894,000 were domestic tourists during the period of 1980 and 2004 (Tibet Regional Government, 2006). It is significant to note that the majority of tourists during the past periods have been the local Chinese, who make the domestic tourists. This group is said to be traveling to experience the different cultures in Lhasa (Wen & Tisdell, 1996).

Since the establishment of Railway line, tourism activities have remarkably increased in Lhasa (Wen & Tisdell, 1996). The railway has boosted both the transportation of large number of visitors to Lhasa and improved the availability of products and services for the locals and the tourists (Wen & Tisdell, 1996). The fact that products and services can easily be accessed has lowered their prices, largely due to the influx of many traders and subsequent competition (Spiteri & Nepal, 2006). This could be partly attributed to the opening of railway transport, which, in essence, is a cheaper means of transport as compared to air. This reduction in travel cost has since attracted more and more visitors to this region everyday, thus changing the economic environment of the area and also promoting the growth of local tourism market. It is no doubt the local traders have taken advantage of this development by developing more recreation facilities such as hotels, restaurants, and shopping mails; and even related tourism services such as travel companies and bus/taxi companies have been established (Tibet Regional Government, 2006). The developmental growth of tourists in Tibet saw the industry contribute to a significant 14.2% to the overall GDP in 2007, making tourism one of the leading industries in the whole region (La, 2007).

Interestingly, Tibet is considered one of least-developed provinces in China and has limited resources to promote local economic development (Ko & Stewart, 2002). Traditionally, livestock breeding and agriculture have been the main drivers to local economy for years (Kiss, 2004). Although the growth of tourism has brought remarkable economic benefits to the local community, the negative influences on local environment and socio-cultural issues have been the center of discussion ever since its inception (Lu, Fu, Chen, Xu & Qi., 2006). Again, environment degradation, damages of heritage sites and conflicts between host community’s rich cultures and the developers are major areas of concern (Lu et al. 2006)

Literature Review

From the past scholarly works, it can be noted that development of tourism in Tibet did not start recently. It was nearly a half a century ago when Tibet was systematically integrated into China Robinson (Simmons, 1994). Along this period of time, the region experienced a significant degree of social as well as cultural transformation under the leadership of central government of Beijing (Simmons, 1994). According to La (2009), the initial stages of Chinese governance, especially during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, sociologists’ ideology was introduced into many aspects of Tibetan lives. Expectedly, Tibetan Buddhism was the prime target during this forcible introduction, where all forms of religious activities were banned in line with Maoist reform and revolution (La, 2009).

The central government at Beijing particularly encouraged the open door policy which aimed at encouraging human and economic interactions with the outside world, with introduction of tourism as the central pillar in economic development (Ghimire & Li, 2001). Understanding the negative and positive impact caused by tourism development to the environment, economy, culture and political climate of Lhasa, Tibet are important areas to be considered for research. The constant conflicts between indigenous residents and the central government especially since 2000 is posing as a major challenge to sociologists, researchers, and the academia fraternity as a whole.

Tourism and Host community and the Government

In spite of Lhasa’s massive modernization since tourism surfaced in the region, Buddhism still remain and dominates the many aspects of life for local Tibetans (Ghimire & Li, 2001). These people make frequent pilgrimage visits to the Potata, the Jokhang Temple as well as major Monasteries in order to make offerings, say prayers, and practice many more religious activities (Ghimire & Li, 2001). In essence, Lhasa still remains the central pilgrimage site for the Buddhists in Tibet.

For the indigenous ordinary Tibetan, the economic value of Buddhism, the idea introduced by tourism, is very new and alien, in contrast to Southeast Asia (Li, 2006). It is only among the few sections of the community in Lhasa composed of Tibetan elites, government officials, and entrepreneurs who acknowledge the economic value of tourism against the traditional believe that does not recognize the mundane economic values and activities that come with tourism (Li, 2006). Li (2006) says, “it is even disrespectful in some respect to associate the economic values of the tourism with the Buddhists” (p.84). According to Sautman (2006) the commodification of the Tibetan religion is naturalized and authorized at national level for the sake of economic progress. Thus tourism acts as a disseminating vehicle which encourages the Tibetans to re-examine their religious traditions; and consider its possible commodity status (Cochrane, 2007; Sautman, 2006).

As frequently observed, the development of tourism is often inevitable; the involvement of the state, particularly with the case of ethnic tourism (Fennell, 1999) is a complex scenario. Since the development of tourism has a potential of stimulating nationalistic or separatists sentiments among the ethnic population, it is often observable how state engage in the systematic control of the process especially the marketing aspect of tourism, putting a lot of emphasis on the ideological aspect of its development (Fennell, 1999). In this aspect, the government is fronting the argument in two perspectives: the economic value of Tibetan traditional culture, and the culture of ethnic (Fennell, 1999; Boniface & Robinson, 1999). On the other hand, the host community is more into the religious view (Buddhism) of the area. To the community and the proponents of the Buddhism, the commodification and ethnicisation of Tibetan culture is an effort by the state to manipulate the Tibet traditional religious beliefs (Boniface & Robinson, 1999). These conflicting beliefs between the state and the local community have been the source of constant conflict in the region.

Tourism and Cultural Sensitivity

In practical sense, it always reasonable to assume that cultural sensitivity will be an automatic issue in any form of development. However, this has not been the case in many tourism hubs in different states of the world since the tourism development proponents seem to drive the development agenda without the obvious involvement of the community (Husband, 1989; Ogutu, 2002)

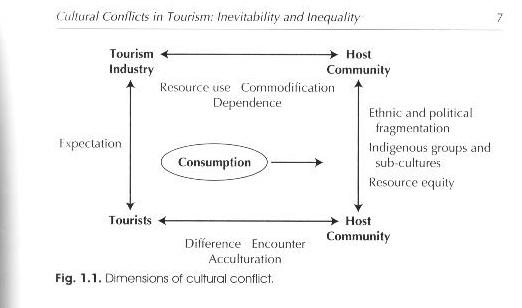

In his book, Tourism and Cultural Conflicts, Robinson (1999) analyzes the conflict that exists between tourism development and cultural preservation through a cycle of diagram as shown below:

From the figure, it can be noted that there are four board planes between which cultural conflicts occur. Adapting a system approach, the interface between the tourism industry which includes the physical mix of accommodation, transports, travel agents and government agencies as promoters and host community is also a rather obvious source of potential conflict. Robinson (1999) highlights that there is a dimension of cultural conflict which is often overlooked in the literature: that which takes place within host communities and not taken into consideration within the tourism development planning. This point of argument could be attributed to conflict between the local Tibetans and the central government of China.

The positive and negative effects of tourist-host exist, and the phenomenon could be linked to the availability and acknowledgement of cultural sensitivity or lack of it (Sautman, 2006 Robinson; 2009). In essence, Robinson (2009) outlines some of the effects of tourist-host relationships, classifying them as either positive or negative as follows:

- Positive Effects includes: Developing positive attitudes about each other; learning about each other’s culture and customs; reducing negative perceptions and stereotypes; developing friendships, pride, appreciation, understanding, respect and tolerance for each other’s culture; increasing self-esteem; and developing psychological satisfaction with interaction.

- Negative Effects: developing negative attitudes about each other; tension, hostility, suspicion and misunderstanding; isolation, segregation and separation; clashes of values; difficulties in forming friendships; feeling of inferiority and superiority; communication problems; ethnocentrism; culture shock; and dissatisfaction with mutual interaction (Robinson, 2009).

Tourism economy and Biodiversity Conservation

According to Husband (1989), the economic benefits derived from tourism should be beneficial to the local residents as this benefit would motivate them to voluntarily conserve the biodiversity. It thus follows that an increased participation of the local community would boost the conservation efforts. However, the study conducted by Xu, Lu, Chen & Liu (2009) indicate that this important linkage between the local community and the biodiversity conservation groups in Lhasa is poor and at worse, lacking in some areas of Tibet. The local residents are marginalized from economic participation in tourism, arguably due to their areas of residents, which are considered remote (Xu et al., 2009). This marginalization of the local communities have left non-local residents carrying out the conservation process at no cost while deriving huge economic income from tourism at the expense of the locals (Xu et al., 2009. It is observed that just a few locals armed with skills, capital, and easily accessible location derive some minimal benefits from tourism (Xu et al., 2009).

Additionally, the exploitation of the natural resources has been enormous in the tourism development in Lhasa, where nearly all permanent operators offer wild plants such as vegetables and fungi, on their restaurant menus, and 26% of temporary operators collect traditional medicinal herbs, wild vegetables or fungi and sell them to tourists as the source of family income (Xu et al., 2009; Scoolte, 2003). This is likely to create degradation of the existing resources, and further increase the degree of conflict between tourism development and the local community of Lhasa.

Besides, Ghimire (2001) highlights the problems related to the rapid growth of Chinese domestic tourism. The environmental sector is one area where limited information exists on the negative impact of domestic tourism, although very little distinction is made between the relative influence of national and foreign tourists (Ghimire, 2001). A number of surveys pointed the main environmental issue was destruction of the natural environment in tourists reserves such as opening the land and dredging river courses in order to develop tourist facilities (Xu et al., 2009). Although domestic tourism has grown at a rapid pace, the expenditure capacity of the average tourists was generally low (Salafsky & Wollenberg, 2000). Most Chinese tourists were far more not willing to accept inferior touristic conditions, while preferring to spend less money rather than to spend more and enjoy better conditions (Salafsky & Wollenberg, 2000).

Economic Leakage in Tourism Development

According to Butler (2006) the participation of the local communities in the tourism development is to boost equal distribution of tourism income and maximize local development potential by reducing import leakage. This is because the leakage of revenue from the local economy is directly linked to the amount of goods imported from outside (Butler, 2006).

In one particular study, it was revealed that tourism income in Tibet is not shared in an equitable manner with the local residents, a disparity that is attributed to the location, skills and capital available in the region (China Tibet News, 2009). The results showed that tourism income is not shared equitably with local residents, and the disparity is due to location, skills, and capital availability (China Tibet News, 2009). It was established that even vegetables and rice are being imported, and many of the commodities in sale are imported from outside the area (China Tibet News, 2009). Furthermore, there are quite large numbers of foreigners who work in the tourism (Baidu Organzation, 2007); a scenario that is in no doubt creates economic leakage.

Tourism and employment

Even though tourism in Lhasa has created more employment opportunity, it has become difficult for the local community to benefit from the industry in terms of jobs. This fact is attributed to several factors, which Salafky & Wollenberg (2000) highlight as transferability of skills, opportunity to acquire and develop new skills, competitive ability of non-locals, and the ability of to maintain the accruing benefits to the locals. According to the study by Salafky & Wollenberg (2000), the present condition of employment in Tibet does not help the local community at the larger Tibet in terms of employment because they are limited with such factors as lack of adequate skills and insufficient opportunity to acquire such skills.

Analysis

It may be true that one of the critical features of modernity is how culture, tradition, and identity are organized within regimes of representation. If this organization is real and true, then tourism may be a primary vehicle for this aspect. The representation of Tibet as a cultural hub is increasingly being naturalized and taken as something real that many scholars and community alike are keen the progress of the process. Although it is apparent that the previous phases of tourism development shows that the socio-cultural and economic controversy surrounding tourism in Tibet were in high octave, the present redevelopment of Lhasa as a “tourism headquarter” is likely to generate more reactions, considering the emerging importance of tourism and the value the community places on their cultural religion.

Tourism and Sustainable Development

The aspect of embracing the World Heritage concept in Lhasa, Tibet is seen as a step forward in an effort to preserve the cultural artifacts of the community. However, it is critical to question how much it costs to establish and implement a clear guideline for conservation purposes. According to Kutay (1992) it costs more to run a building than it does to build one. It can thus be observed that if awareness and understanding of the requirement is put in place to integrate a successful World Heritage site, then a proper communication is required to establish a proper link with all stakeholders (Henderson, Emily, Yeh, Elvidge & Baugh, 2003).

The recognition of the community as stakeholders is in no doubt a critical aspect of establishing a well-balanced destination for tourism. As Salafky & Wollenberg (2000) observe, a good environment that gives room for innovative activities is likely to spur sustainable development; thus ensuring the best operational phases to enhance a lengthy project beyond the recognizable scope of the designers. For example, the World Heritage Sites should be put in a manner that would enable the critical stakeholders (local residents) feel more of “residents” than “visitors” to make them more friendly to the plans and actions for boosting tourism.

The guidance of tourism development in the past and present will definitely impact either positively or negatively on the future generation. If the sustainability of any project like the refurbishing of World Heritage Sites is judged in the future as either success or failure, that is, either becoming useful or redundant respectively in future, then it is critical to note that what is to be removed or left for future is critical and important. Understanding what is to be removed or left can only be well understood by the local community (Xu et al. 2009).

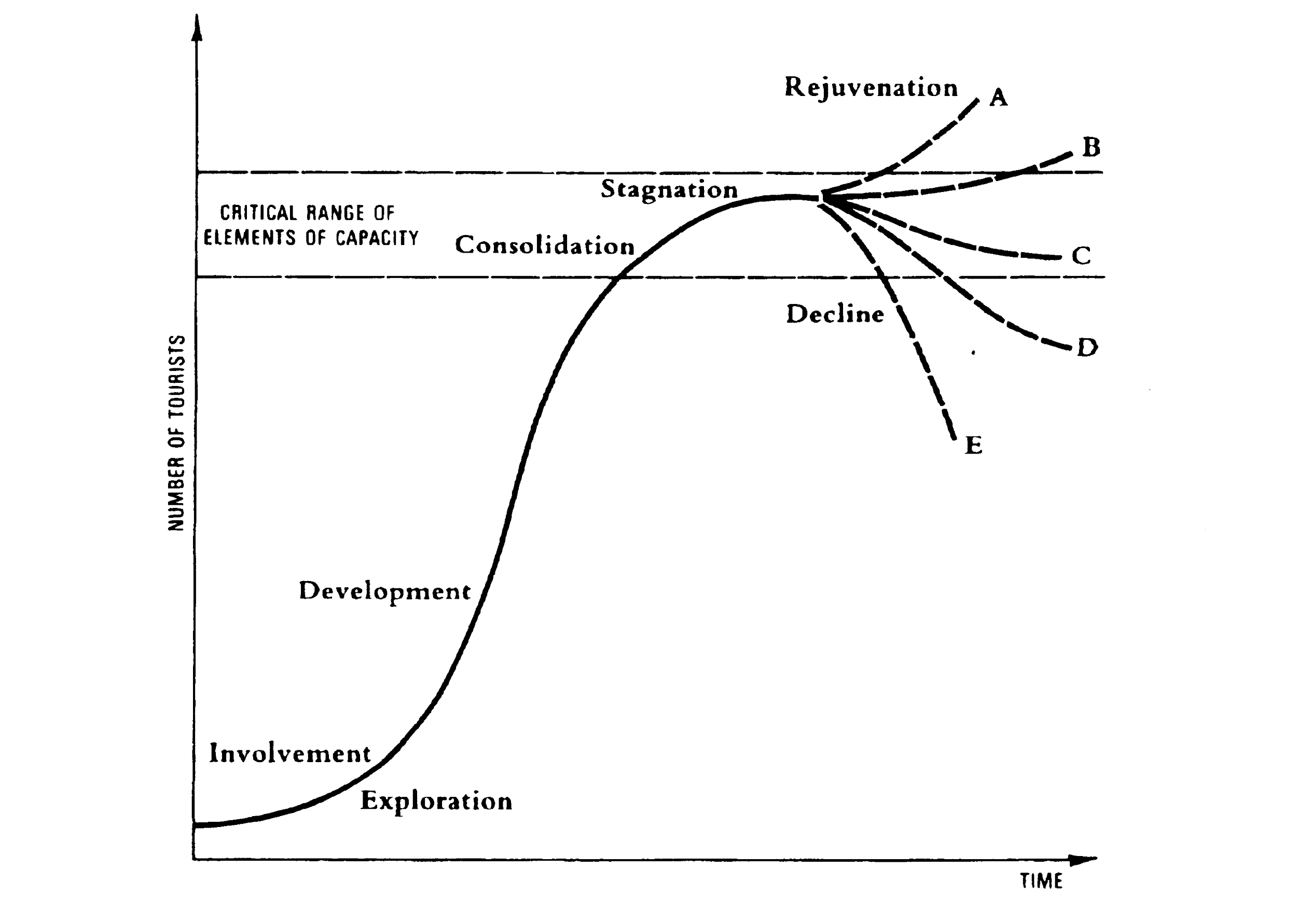

‘The Tourism Area Life Cycle’ is the theory developed by Butler (2006). In Butler’s view, not all tourism areas have timeless cultural attractions like Rome, or natural attractions like Niagara Falls, that is, most resort regions, like any other product, have a predictable life cycle (Butler, 2006). The Tourism Area Life Cycle concept is similar to the product life cycle and it can provide advice regarding appropriate timely action aimed at avoiding regional decline which may otherwise be inevitable (Butler, 2006).

The Tourism Area Life Cycle states the development of one tourism destination will follow in six stages: Exploration, Involvement, Consolidation, Stagnation, and either Decline or Rejuvenation. Butler suggested that tourism numbers should be used to construct the typical “S”-shaped life cycle curve (Butler, 2006).

The figure below, adopted from Butler (2006), illustrates the “S”-shaped life cycle curve:

The socio-cultural conflicts analysis, based on the existing western tourism theory such as Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) theory (Butler, 2006) gives a clear view of the Lhasa’s tourism- conflict development hence the solutions can be derived.

Physical strategy

This involves reinforcing the heritage sites and redeveloping resident houses in destinations to improve the capacity of attractions. At present, there are quite a good number of tourism resources that have not been exploited like the local Tibetan culture and natural landscape. In spite of the recent development of infrastructure, it was revealed that few tourists stay in the area for more than a day (Lu et al. 2003). This was attributed to the insufficient residential houses (Lu et al. 2003). It is therefore important to improve the residential houses and reinforce the heritage sites that would consequentially make more tourists stay for longer in the region. This is because it is noted that the area still has a larger carrying capacity and hence still hold a bigger tourism potential (Li, 2006).

Educational strategy

Good educational strategy is considered as one of pillars of a better development (Kutay, 1992). It is necessary to develop strategic educational methods not only to make tourists understand and respect local customs and traditions, but also assist local community acquire skills to manage their own resources and get the emerging employment opportunity. In essence, given opportunity to study how to manage their environment, the community is able to derive direct benefit from tourism (Kutay, 1992. In an economic and human aspect point of view, it is essential to give the local community equal educational opportunities to education to enable them acquire skills for equal opportunity in competition for employments.

Economic strategy

In some study, it was established that local residents do not get equitable share of the resources from the tourism activities, an aspect that may have contributed to the constant rebellion (Li, 2006). Again it was noted that much of the resources generated from the tourism sector in this region is taken by the local council, who seem to control everything from types of crops to grow and the amount to be imported (Sautman, 2006; Li, 2006). This area has failed since large amount of resources consumed by tourists such as vegetables are imported hence making the locals vulnerable economically (Li, 2006).

The economic strategy is very crucial in the prosperity of Lhasa region. The economic benefits are known to play a very significant role in the prosperity of both the local people and the government. Some of the important strategies like increasing the prices such as accommodation fees during the high seasons in order to control the flow of visitors in the destinations and reducing the prices in the low reasons in order to attract more visitors. This strategy is likely to reduce pressure on the available resources during high season and of course increase the maximum utilization of the resources during low season.

Regulatory strategy

Lhasa as the religious capital of the region will require some regulatory measure to curb the negative influence of tourism that come with influx of tourists from different cultures of the world. This is likely to reduce the anti-tourism sentiments from the local community and social critics. Such legislations and rules destinations to limit the tourist’s activities or behaviors which may cause the negative influences to local communities such as the smoking free, drinking, prostitution, drug trafficking and consumption, etc. should be banned.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Tourism development requires a delicate balancing act. The need for revenue in Lhasa by increasing attractions sites for visitors is a potential damage to the sites and generation of conflicts with the social norms and traditions. It is also a rich source of revenue to the central and regional government, and a potential livelihood source for the local people if well managed. It can be observed that cultural brokers will definitely seek to make profits while others will try to avoid the tourists. It is thus important to observe with keen interest, the need to balance the two phenomena: socio-cultural aspect and economic prosperity. The local community should therefore be empowered to get, with such offers as start-up capitals for agricultural development and business and efficient educational facilities.

Since it is known that the local communities have been marginalized in the process of developing the tourism sector in Lhasa and the larger Tibet largely due to their physical locations, it is important to open further the areas where these locals live with more infrastructures like roads to facilitate their participation.

Strategic educational methods will not only make tourists understand and respect local customs and traditions, but also assist local communities acquire skills to manage their own resources and get the emerging employment opportunity. That is to say that the locals should be given opportunities to manage their environment, considered a process of learning itself. This would enable them to get the economic benefit first-hand as opposed to the current situation.

The fact that resources from tourism are not shared equally makes matters worse for the prosperity of the sector. This disparity resulting from the location, skills and capital available in the region should be critically looked at in a more human way, if there is any expectation of success for the projects to develop the tourism industry in Lhasa. In other words, the resource-sharing structure should be put in place to ensure a good share of income earned from tourism is reinvested back into the community to boost economic development and foster understanding between the stakeholders.

Reference

Baidu Organzation. (2007). The introduction of Qinghai-Tibet Railway. 2009. Web.

Boniface, P., &. Robinson. M. (1999). Tourism and Cultural Conflicts. Oxford University Press.

Butler, R.W. (2006). The Tourism Area Life Cycle: Applications and Modifications. (Ed.). (Vol.1). UK: Channel View.

China Tibet News. (2009). The Characteristics of Tibet tourism in 2008. Web.

Cochrane, J. (2007). Asian Tourism: Growth and Change (Ed.). UK: Elsevier.

Fennell, D.A. (1999). Ecotourism: An introduction. New York: Routledge.

Ghimire, K. B. & Li Z. (2001). The Economic Role of National Tourism in China. The Native Tourist London, UK: Earthscan, pp.86-108.

Henderson, M., Emily T., Yeh P. G., Elvidge C, & Baugh K. (2003). Validation of urban boundaries derived from global nighttime satellite imagery, International Journal of Remote Sensing. 24 (3): 595-609.

Husband, W. (1989). Social statue and perception of tourism in Zambia. Ann Tourism Res. 6, pp. 237-255.

Kiss, A. (2004). Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds?. Trends Ecol Evol. 19:5, pp. 232-237.

Ko, D.W., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Manage. 23, pp. 521-530.

Kutay, K. (1992). Ecotourism marketing: capturing the demand for special interest nature and culture tourism to support conservation and sustainable development. Presented to the Third Inter-American Congress on Tourism, Cancun, Mexico.

La, Z. (2009). The Qinghai-Tibet Railway and Tibetan Tourism Development. Web.

Li, F.M. (2006). Tourism development, empowerment and the Tibetan minority: Jiuzhaigou National Nature Reserve. UK: Elsevier, pp.226-238.

Liang, M.Z. (2008). Lhasa Tourism Development. China: Guandong Travel and Tourism Press, pp.316-326.

Lu, Y.H, Fu B.J., Chen L.D., Xu J.Y & Qi X. (2006). The effectiveness of incentives in protected area management: an empirical analysis. Int J Sustainable Dev World Ecol. 13 , pp. 409-417.

Ogutu, Z.A. (2002). The impacts of ecotourism on livelihood and natural resource management in Eselenkei-Amboseli ecosystem. Kenya. Land Degrad Dev. 13, pp. 251-256.

Robinson, M. (1999). Cultural Conflicts in Tourism: Inevitability and Inequality. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing, pp.1-32.

Salafsky, N. & Wollenberg E. (2000). Linking livelihoods and conservation: a conceptual framework and scale for assessing the integration of human needs and biodiversity. World Dev. 28:8, pp. 1421-1438.

Sautman, B. (2006). Tibet and the (Mis-) Representation of Cultural Genocide. England: Palgrave Macmillan. pp.165-272.

Scoolte, P. (2003). Immigration: a potential time bomb under the integration of conservation and development. Ambio. 32 , pp. 58-64.

Simmons, D. G. (1994). Community participation in tourism planning. Tourism Manage 15, pp. 98-108.

Sofield, T. & Li S. (2007). Indigenous minorities of China and effect of Tourism. UK: Elsevier, pp.265-280.

Spiteri, A., & Nepal, S.K. (2006). Incentive-based conservation programs in developing countries: a review of some key issues and suggestions for improvements. Environ Manage. 37:1, pp. 1-14.

Telfer, D.J., Sharpley R. (2007). Tourism and Development in the Developing World. New York: Routledge Publishers.

Tibet Regional Government. (2007). Statistical Data of visitors in Tibet. Web.

Wen, J. & Tisdell C. (1996). Spatial distribution of tourism in China: economic and other influences. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, pp.266-284.

Wild, C. Cooper C.P. & Lockwood A. (1994). Issues in ecotourism: progress in Tourism, Recreation, and Hospitality Management. Chichester: Wiley. pp. 12-21.

Wunder, S. (2000). Ecotourism and economic incentives – an empirical approach. Ecol Econ. 32, pp. 465-479.

Xu, J., Lu Y., Chen L., & Liu Y. (2009). Contribution of tourism development to protected area management:local stakeholder perspectives. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, Vol.16, Issue.1, pp.30-36.

Yamamura, T. (2004). Authenticity, ethnicity and social transformation at World Heritage Sites: tourism, retailing and cultural change in Lijang, China. UK: CABI Publishing, pp.185-200.

Yeh, ET. (2004). Property relations in Tibet since decollectivization and the question of ‘fuzziness. Conservation and Society, Vol. 2 (1):108-131.