Introduction

Banking has evolved in several ways throughout the decades. Compared to previous years, banks now provide a wider variety of goods and services, and they do it more quickly and effectively. However, banking’s core role continues to be the same as it has historically been. Banking institutions utilize a society’s excess cash (investments and deposits) by lending to individuals for different objectives, including the purchase of houses and automobiles, the launch and expansion of enterprises, and the education of their children. Banks are critical to the economic stability of a country. Banks are the primary option for borrowing, saving, and investing for millions of Americans in the United States. This culture was not built in a day; it was founded on America’s rich banking history that can be traced back to the establishment of the first bank in 1791.

From the First Banks: 1791 to 1832 to the Banking Crisis: 1929 to 1933

The majority of early federal union states required bank operators to obtain special approval from the state government to begin operations. The Bank of the United States, a central bank established in 1791 by the country’s first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, offered an added dimension of governance for a time (MacLeod et al., 2018). Its authorization from the United States Congress was voided in 1811. Five years later, a new Bank of the United States was established, which remained in operation until 1832.

During this era, city bankers were notorious for being exceedingly selective over who they gave money to and for how long. Bankers traditionally provided solely medium-term loans to ensure they had sufficient cash reserves to satisfy emergency requests from depositors (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2014). Thirty to sixty days was considered standard. Ordinarily, producers and merchants could utilize these monies to compensate vendors and employees until the items were ready to be sold to consumers. They planned to use the proceeds from the sale to offset the bank debt. More flexible lending conditions were found to be prevalent in less developed areas of the country. Farmers could regularly get bank loans to purchase property and machinery, as well as to fund the shipping of agricultural goods to markets (FDIC, 2014). In addition, loan liabilities were higher than usual due to climate and market circumstances volatility.

States took on the role of bank oversight in 1832 when the new Bank of U. S. failed. However, Sumner (2018), notes that in many cases, this oversight was insufficient. A bank would issue its currency and use it as collateral for lending. These banknotes were designed to be exchangeable for currency, mainly in the form of gold or silver. Examiners were responsible for verifying that the bank was able to reclaim its unsettled banknotes (FDIC, 2014). Several banknote issuers were left with the useless paper since this was not often done. With such a wide assortment of notes, it was often challenging or hard to tell which ones were good and bad.

By 1860, the U.S. had amassed over 10,000 special banknotes. This resulted in adverse impacts on commerce across states. Moreover, anti-counterfeiting was rampant, leading to the collapse of hundreds of banks as many went bankrupt (FDIC, 2014). There was a strong desire for a monetary unit that could be used everywhere in the country with no risk. Accordingly, the National Currency Act was approved by Congress in 1863. One year later, the National Bank Act was enacted by President Lincoln in 1864 as an amendment to the statute (Xaviant, 2016). These statutes introduced a novel national banking framework and a new government institution led by an Office Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) (Rothbard, 2020). To manage and monitor the new financial system, the Comptroller was responsible for enacting rules and conducting regular inspections.

There was a noticeable change, as the new system performed flawlessly. National banks purchased sovereign bonds in the United States, filed them with the Comptroller, and were compensated with national legal tender. The notes eventually gained circulation when they were loaned to borrowers. When a national bank collapsed, the government liquidated the bonds placed on reserve and repaid the note owners. There was never a single instance of a national bank note holder losing their funds (FDIC, 2014).The production and distribution of national bank notes was a time-consuming procedure that required several steps. After the notes were engraved and printed (Initially printed by private printers and subsequently by the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing), the banknotes were recorded into the OCC’s records, then sent to the engraver, where the Treasury Department’s seal was imprinted on each (FDIC, 2014).

Subsequently, the banknotes were delivered to the bank, whose identification was printed and authenticated by two senior bank executives. After this process, the notes were considered eligible for distribution. Until the introduction of Federal Reserve notes in 1914, national bank notes remained the basis of the country’s monetary base (FDIC, 2014). National bank notes were lavishly decorated with scenery and pictures from American heritage. Their intricate design was meant to thwart forgers. Indeed, national banknotes are prized by collectors nowadays because of their exceptional engravers.

The global depression that began in 1929 was a catastrophe for the banking industry. Over 1,000 American banks collapsed towards the end of 1931, as debtors forfeited and bank holdings depreciated in worth (FDIC, 2014). This sparked moments of panic across America, with clients having to queue up before daybreak, hoping to withdraw money before the bank depleted its reserve. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s main priority was to deal with the financial crisis. On March 5, 1933, the day after assuming power, Roosevelt ordered a bank holiday, shutting all of the country’s banks until they were reviewed and either reopened or liquidated in an organized manner (MacLeod et al., 2018). The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency was responsible for most of this operation. Congress authorized federal deposit insurance through the Banking Act of 1933. Accounts were insured up to a maximum of $2,500 per depositor, which is equivalent to $100,000 in today’s currency (FDIC, 2014). Additional legislation governing bank activity and competition was enacted to control bank risks and ensure the masses that banks were safe and would remain so in the future.

There have been many years of tension between the Federal Reserve and the executive branch as well as Congress. Prior to 1951, when the dominance battle with Treasury ended, the federal government had a greater say in running the Federal Reserve (FDIC, 2014). Still, since then, it has worked mainly autonomously away from politics. Nevertheless, the Federal Reserve has to respond to queries and discuss topics of concern with both the House and the Senate on a frequent basis, as mandated by law (FDIC, 2014). As an autonomous central bank, this model has emerged as a blueprint for governments all over the globe to follow.

Community Banking in the United States

The term “community bank” is not legally defined or uniform. As a result, defining what constitutes a community bank has been challenging in the past. The FDIC began researching community banks in 2012 and transformed its approach to spotting these financial institutions (FDIC, 2022). The FDIC now defines community banks as those with liabilities below $10 billion, which is still a relatively broad approach (FDIC, 2022). Nevertheless, the qualities of these establishments are a bit simpler to identify than they were before. In general, community banks offer typical banking services to the people who live in their areas. These financial institutions tend to be supportive of their local communities, collecting the majority of their core deposits from local customers and lending to local enterprises. Similarly to how some individuals choose to shop locally and promote small enterprises, others may want to bank with a community bank.

According to the FDIC, community banks provide conventional banking offerings in local areas, receive deposits locally, and provide the majority of their credits to small and medium-sized enterprises. Locally managed community banks are often privately owned and operated than bigger publicly listed banks backed by shareholders. Community banks are often regarded as “relationship bankers,” meaning that they have a strong connection with their clients as well as specialized experience and knowledge of the neighbourhoods in which they operate (Waupsh, 2017). Credit decisions made by small banks and loans unions may be less structured than those made by major banks, making it feasible for individuals and small enterprises to get approval for credit that a bigger institution might otherwise deny.

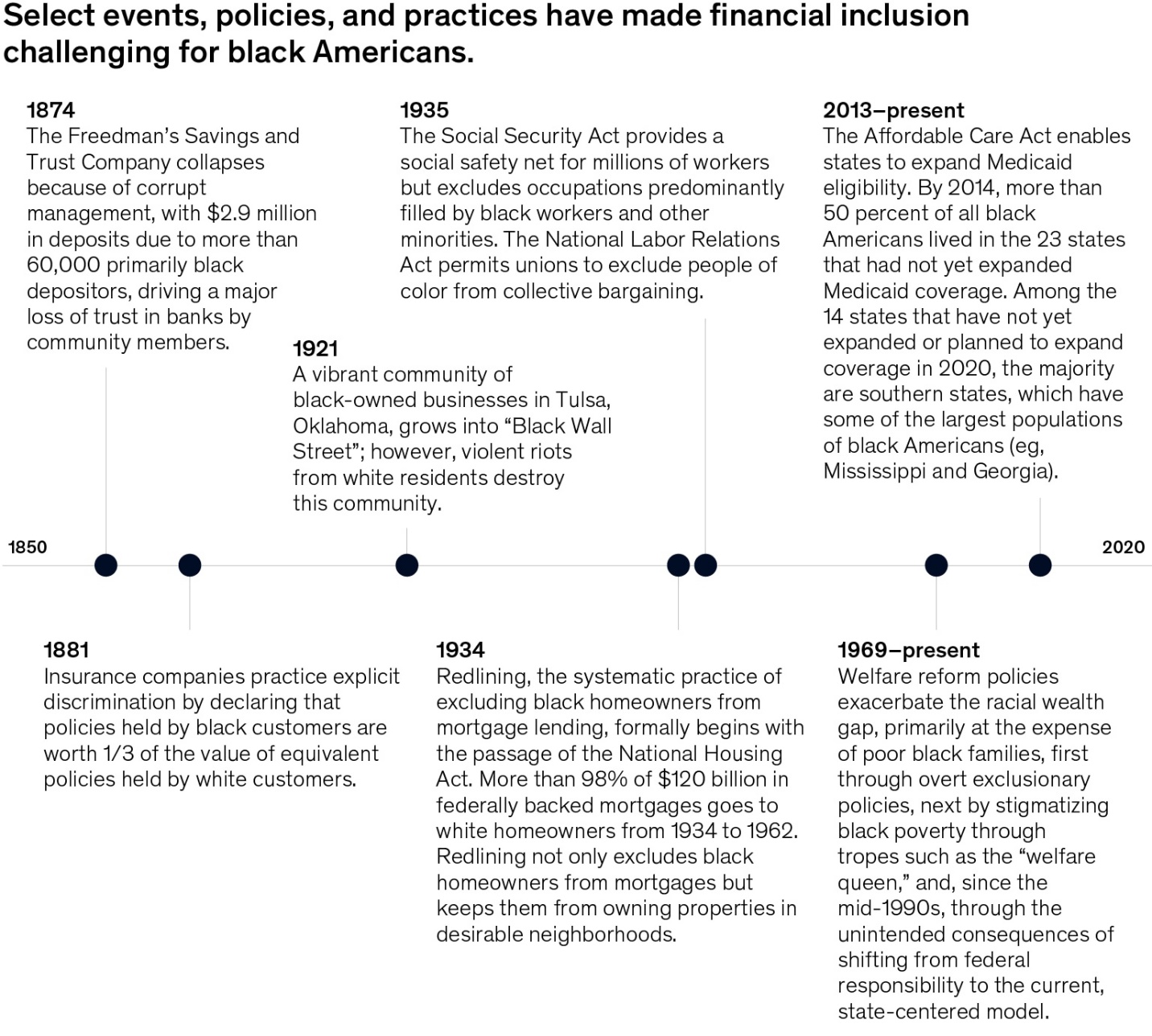

Inaccessibility to financial services is not a mere manifestation of the income difference between marginalized communities and white people but is a contributing factor to that divide. Many African American households struggle to turn their earnings into wealth because they do not have the financial means to save, invest, and protect themselves against hazards on a logical basis (Darity Jr et al., 2018. However, developing that connection has not been straightforward. For years, racist policies and initiatives have exacerbated the racial wealth gap for African American folks and their families. Figure 1 shows this clearly:

Note. Between 1874 and 1969, and to a lesser degree, up to the present day, Black families have endured the cumulative impacts of generations of discriminatory regulations and policies that led to racial wealth. From The case for accelerating financial inclusion in black communities, by Aria Florant et al., 2020, McKinsey & Company.

Even though financial service inclusivity levels have increased in recent decades, the unpleasant truth is that millions of customers and small companies still lack access to any assistance from a credible financial service provider. As per Federal Reserve statistics, nearly one-fifth of Americans do not have a checking account and depend on money exchange services, pawnshops, and payday creditors for financial assistance (The Fed, 2018). Several small enterprises utilize non-traditional lending and banking channels. Cultural factors play a significant role in this predicament: minorities and immigrants are more prone to shun giant banks and think neighborhood financial firms are comparable.

Furthermore, financial technology applications that cater to the in-demand necessity of sending foreign payments directly to these demographics are a focus of attention. It has always been the pride of local financial firms to provide financial services to the community while giving possibilities to people who may otherwise be left out. Despite this, many American people do not have access to a bank in their personal and professional lives (FDIC, 2021). Community banks and credit unions may easily fill this need with some minor tweaks. Below are four ways in which they might take advantage of this sector:

Targeted outreach- If financial firms wish to expand to minority groups, they should first understand their challenges. Offering advertising in different languages and recognizing the unique problems experienced by these communities would relax and reassure these prospective clients.

Financial education- As previously stated, a lack of knowledge or misleading facts is to blame for a few shortfalls in financial inclusion. People who do not have bank accounts sometimes associate modest financial firms with huge ones, but this is a mistake since the former is friendlier to small enterprises and community residents.

Digital first- As smartphone consumption increases, fintech companies increasingly focus on previously unbanked groups. This demographic prefers digital alternatives when it comes to banking since they do not have to commute, reside near an establishment, or encounter biases. The community’s establishment must match these offers, maybe by cooperating with other organizations.

International services- Foreign payments are nothing new for immigrants with global relations. Many people transfer money to other countries daily, and minorities are often the driving force behind small enterprises. New consumers may be onboarded and introduced to additional items by providing easy access to these services.

Banks not affiliated with community organizations (conventional banks) serve a vital role in economic development and offer crucial assistance to several low-income, rural, and minority populations. When it comes to serving hard-to-reach areas or those considered too unstable, the banking system faces challenges from a systemic failure. On the contrary, entities where disadvantaged and high-risk groups operate, have substantial opportunities to provide high-quality services to their communities.

Finance-Related Events and Acts in the 1970s

The 1970s

Several events occurred during the start of the 1970s. Rapidly increasing oil costs triggered an inflationary cycle, which resulted in an increase in interest rates, triggering depression (FDIC, 2014). Similarly, the costly Vietnam War ended, and automation gained traction. Notably, less-developed countries’ debt burden climbed from $29 billion to $327 billion throughout this decade (FDIC, 2014). These events heavily influenced the enactment of various finance acts throughout the 70s.

1970

The Automated Clearing House Interbank Payment System was established as a commercial enterprise to process checks.

- Congress established the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) to provide funding for home financing in the United States (FDIC, 2014).

Bank Holding Company Amendments (BHCA) of 1970

The 1956 BHCA opened a substantial gap regarding the non-bank activity. These reforms were prompted by increasing political anxiety over the emergence of giant corporations. The BHCA was amended in 1970 in reaction to the rise of one-bank holding entities:

- Obtain Federal Reserve Board clearance for the formation of a bank holding firm

- Relax limitations on non-bank activities (FDIC, 2014).

1971

In an effort to restore the economy and contain inflation, President Richard Nixon unveiled his “New Economic Policy.” This approach represented a significant departure from typical fiscal policies. Likewise, President Nixon devalued the dollar and eliminated the currency’s gold conversion to promote the consumption of U.S. products in international markets (FDIC, 2014). This depreciation allowed the dollar’s value to fluctuate in global markets. President Nixon imposes wage and price limitations. The president also introduced legislation in Congress to remove the automobile tax, offer tax incentives for company investments, and lower the individual income tax.

1973

The 1973 Middle East War had a significant impact on inflation. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) raised oil prices, reduced output, and enforced an oil blockade on the United States, resulting in even greater inflation and a trade imbalance (FDIC, 2014). The 1973 Middle East War had a substantial impact on inflation. Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) hiked oil prices, curtailed oil output, and enforced an oil embargo on the U.S. caused even greater inflation and a trade imbalance.

1974

- The oil ban precipitated the 1974-1975 global economic downturn, exacerbating the overall debt of less-developed countries (FDIC, 2014).

- Due to inflation, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) raised the deposit insurance maximum from $20,000 to $40,000 (FDIC, 2014).

Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975 (HMDA)

This act:

- Urged banks and savings and loans to provide mortgage loans in low-income communities

- Directed banks and savings and loan associations to record their lending operations (FDIC, 2014).

1977

Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977

This act:

- Required banks and savings and loan associations to address the credit requirements of local communities, primarily low-income neighborhoods

- Directed the FDIC to conduct CRA conformity audits of non-member state banks (FDIC, 2014).

1978

The International Banking Act of 1978

This legislation governed the founding, operation, and management of foreign banks in the United States (FDIC, 2014).

Financial Institutions Regulatory and Interest Rate Control Act of 1978

This act:

- Created the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), which consisted of the Federal Reserve Board (FRB), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the FDIC, and the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) (FDIC, 2014).

- Specified the criteria for bank insider dealings.

- Specified minimum requirements for electronic funds transfer (EFT).

- Enacted legislation for the imposition of civil money fines upon individuals and banks. In 1979, the FFIEC commenced operational activities (FDIC, 2014).

Minority-owned and community-based banks are not immune to racial discrimination. Small and community banks’ activities are often less scrutinized since the public impression, restricted geographic reach, and lesser percentage of deposits are not heavily scrutinized. Racially-targeted tendencies in redlining demonstrate how banks operate in minority communities and how they collect additional fees in return for this commitment. A classic examples is lower-quality loans with higher interest rates. Black and Latinx persons and regions were singled out throughout the subprime mortgage craze for exploitative bad loans, clearly demonstrating this relationship (Faber & Friedline, 2020).

American Bankers Association

Banks and other financial organizations form the American Bankers Association (ABA). The organization was established in Washington, D.C., in 1875 and served as its base (American Bankers Association, 2022). This organization represents the bank industry. Training, education, information, and support for its members are its primary goals. The ABA is a gathering place for a variety of financial organizations, including banks. Businesses, savings groups, trust companies, and money center banks are among its members. The emergence of the American Bankers Association extends back to 15 decades ago, when James Howestein, a banker from Missouri, found himself in a precarious financial position.

To get himself out of this mess, Howestein had to depend on the advice and insight of his associate bankers, with whom he corresponded often. In light of his newfound insight, he immediately saw the potential of the bankers’ brotherhood association. It was Howestein, in 1875, who brought together a cohort of 17 other bankers in New York City to prepare for the inaugural meeting of the American Bankers Association (ABA, 2022). New York City, Saratoga Springs, was the site of the organization’s inaugural debut on July 20, 1875. In the beginning, there were 349 bankers from 31 states and the District of Columbia participating. According to the original document, the organization had to:

- Enhance the general value and welfare of financial institutions and banks.

- Ensure that all actions are carried out consistently.

- Guarantee that considerations about financial and commercial applications are adequately considered. This comprises laws and conventions that are perceived to impact the financial interests of the whole country. All of them are designed to safeguard banks from losses caused by criminal activity.

In 1903, the American Bankers Association established the American Institute of Banking as one of its first projects. It was created to help those who want to work in banking but do not have a background in law or finance pursue a career in that field (ABA, 2022). ABA essentially provided technical education through examinations and accreditation via local chapters. ABA’s membership has grown after the Federal Reserve System was established (FRS) (ABA, 2022). State-chartered banks could opt out of the FRS requirement to join a Federal Reserve Bank.

Bankers and state associations gave $40,000 to the ABA’s Educational Foundation in 1925 to commemorate the ABA’s golden jubilee. The goal of the scholarship fund was to give financial aid to worthy students who wanted to pursue careers in the financial services industry. ABA celebrated a huge victory in November 1999 when the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act was approved (ABA, 2022). Congress enacted the law because banks were in desperate demand of unique disruptive instruments to improve customer service. The ABA was on the verge of being abolished in 2007 (ABA, 2022). ABA thus decided to join forces with America’s Community Bankers to form a new organization. As a consequence of the merger, the financial sector’s biggest trade group, which represents 95% of the sector’s holdings, was formed.

The Key Roles of ABA

Advocating on behalf of its members is among the ABA’s primary responsibilities. Contenders for both the House and Senate are also supported financially by the organization. Approximately 2 million individuals are employed by ABA member financial institutions and banks, which control 95% of the sector’s wealth (ABA, 2022). The American Bankers Body is the country’s biggest banking trade organization. It provides a variety of goods and services across a range of fields comprising; including employee training, investment management, asset management, insurance, consulting, and risk and compliance. Many activities have been carried out by the American Bankers Association, including the following:

- Advocating on behalf of American banks and bankers before federal and state governments

- Developing quality standards for the industry

- Providing education and distributing banking goods and offerings to its membership

- Fostering industry agreement on critical problems, namely providing legal and public relations help to financial institutions

- Supporting its members’ professional growth via the sponsorship of events (ABA, 2022).

Lobbying

The American Bankers Association is quite aggressive in petitioning Congress in favor of financial interests. Representative lobbying initiatives encompass the American Bankers Association’s attempts to deregulate portions of the banking sector, which resulted in the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (ABA, 2022). The American Bar Association has also advocated for significant adjustments to the legislative environment, notably the relaxation of limits imposed by the Volcker Rule and derivatives rules. An additional area of emphasis for the ABA’s legislative activities has been the abolition of credit unions’ tax-exempt designation, which has been a source of contention for the organization. Historically, credit unions serviced a narrow, highly focused client base, like firm workers. Credit unions have increased their subscriber base and prospective consumer base over the years. Several credit unions already have holdings in excess of $1 billion, rivaling the scale of huge banks (ABA, 2022). According to the American Bankers Association, credit unions have grown so similar to banks that their tax-exempt designation is not warranted.

Outreach and Education

The ABA Housing Partners Foundation, founded in 1991, work to improve the lives of low- and moderate-income families in communities around the United States by promoting access to affordable housing. The target regions include Chicago, New Orleans, Boston, Orlando, and many more (ABA, 2022). Habitat for Humanity has benefited from the work of the Housing Partners Foundation’s member bankers, who have donated their time and assets to help build houses for the less fortunate. Get Smart About Credit and Educate Children to Save are just two of the many initiatives offered by the ABA Foundation to assist bankers to inform their neighborhoods concerning financial planning (ABA, 2022). As part of the ABA’s mission, it also holds conventions and manages a wide range of online workshops and accreditations. A wide range of resources is available to subscribers, both online and face to face.

CRA- Community Reinvestment Act

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was passed in 1977 to avoid redlining and urge savings and banks organizations to meet the lending requirements of all parts of their neighborhoods, specifically low- and moderate-income areas and people. The CRA broadened and defined a long-held idea that banks would fulfil the efficiency and requirements of their surrounding communities (Berry, 2013). In the present era, the CRA and its implementing regulations demand governmental monetary institution authorities evaluate every bank’s performance in accomplishing its obligations toward the community and take that performance into account when assessing and authorizing charters, acquisitions, mergers, etc. and division openings (Berry, 2013). The governmental monetary institution authorities are the OCC, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and the FDIC.

Policymakers are not required to utilize ratios or standards prescribed by the CRA or enacting rules in the review or registration process. Furthermore, the CRA does not compel banks to undertake high-risk lending that puts their existence at peril. Conversely, the CRA’s efforts cannot conflict with the bank’s secure and healthy processes. The purpose of the CRA is to incentivize banks to assist in the reconstruction and revitalization of local communities by making prudent financial decisions and using strong business decisions.

Additionally, CRA establishes a mechanism for depository entities and local groups to collaborate to offer access to lending and other financial products for low- and moderate-income populations. The CRA has prompted banks to build more offices, extend their service offerings, and give a range of social improvement credits and projects (Berry, 2013). Likewise, the CRA has pushed banks to make significant pledges to local and state governments and social welfare groups to expand lending to disadvantaged areas of local sectors and communities.

Banking and Financial Institutions Have Failed

Benefits promised by deregulation and financial innovation were greater risk distribution, reduced credit costs for businesses that would spend more, and extra affordable mortgages for millions of individuals. Indeed, it was difficult to resist the pull of letting these market forces operate unhindered by government intervention, yet in reality, inefficient financial markets are a problem. For the American dream to become a reality, one must have capital. Unfortunately, consumers and small-business owners have different levels of access to financing depending on their race in the United States. In other words, America’s banking and financial sector has failed to ensure financial inclusivity.

In neglected rural and urban populations, racial prejudice and different kinds of market inefficiency have resulted in credit and banking shortages. There is a strong relationship between bank outlet availability and residential mortgage issuances in low-income communities (Van, 2020). That is, the beneficial impacts of bank outlet availability become greater the nearer the branch outlet is to the area. Additionally, associations are related to increased loan accessibility in the small-business financing sector (Van, 2020). To the Federal Reserve, most individuals in the United States had a checking account in 2019. They depended on credit unions or conventional banks to satisfy their banking requirements, although there were gaps in banking accessibility (The Fed, 2019). The Fed report also showed that 6% of adults in the U.S. were unbanked, indicating that they lacked a savings, checking, or money market account. Unbanked individuals utilized unconventional financial services, including money orders, check cashing, pawn shops, vehicle title loans, payday loans, and tax return advances at a rate of 40% in 2018 (The Fed, 2019). For example, the percentage of people without a bank account or the underbanked increased among low-income families and those with a low level of education, such as Black and Latino.

Black individuals had the greatest percentage of unbanked and underbanked people in 2019, rendering it harder for them to save money. Compared to mostly white communities, those with a majority of Black or Latino residents have fewer alternatives for accessing financial services. Owning a house is the most frequent means of accumulating wealth and transferring it from one generation to the next in the United States. The history of racial disparities in eligibility for residential house mortgages in the U. S. encompasses the practice of redlining, regionally targeted exploitative lending, lending criteria stereotyping, and racial contractual obligations (Sood et al., 2019). Thus, what remains consistent is the systemic framework of racial segregation and discrimination, as well as the significant social distance that exists between policymakers at conventional financial firms and members of minority groups.

Mortgage loan documents obtained under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act indicate extremely major discrepancies in acceptance rates since mortgage loan requests of African American applicants are thrice as likely to be declined. Comparable visible indices of creditworthiness show that race has a statistically and financially considerable influence on request choices (Broady et al., 2021). The discrepancies are likely understated, given the creditworthiness restrictions alone could be the product of other processes mentioned in the preceding paragraphs. There is no question a need for new research that reveals loan discrepancies utilizing the accuracy of contemporary statistics.

Minority families have a lower rate of business shareholdings and company assets, which contributes to the racial, and economic disparity. The most significant constraint on the development, expansion, and progress of African American-owned enterprises is a lack of finance (Broady et al., 2021). Access to financing is a hurdle for Black businesspeople when it comes to starting enterprises. Previously, race and gender-related characteristics have been examined on accessibility to company credit lines. The findings indicate that black-owned businesses earn lower credit ratings than predicted and that white-owned ventures with comparable company qualities are evaluated more positively (Henderson et al., 2015). There has never been a level playing field when it comes to business entrepreneurship for black Americans.

Essentially, increasing financial inclusiveness will assist in the resolution of historical issues and the better preparation of minority households for the future. Notably, economic well-being among African-Americans has been hampered by discriminatory policies and methods ranging from restricted access to government mortgage loans to geographic impediments to physical bank outlets. Inequalities such as this have concrete and far-reaching consequences for black families and communities. Enhancing financial inclusiveness is not just a communal, social commitment to help American households who have been chronically disenfranchised. Still, it is likewise an essential step in securing these families’ economic futures. Minority households will have enhanced possibilities to reinvest and expand their money, which would, in turn, promote higher economic activity if they were better represented in the banking sector.

Financial institutions would have expanded prospects as a result of the participation of minority groups in the financial system. According to Broady et al. (2021), financial companies might earn an extra $2 billion in yearly income if African Americans are accorded equal access to credit and monetary services as white Americans. Banking and finance corporations might earn over $55 billion in extra revenue annually if minority groups achieved complete equality with white Americans regarding wealth.

Banking institutions have also limited marginalized groups’ access to credit. The inability of African-Americans to get the credit has pervasive ramifications for their financial well-being. While vehicle possession is necessary for many places for commuting to work and maintaining a career, it is particularly costly for those who are financially disadvantaged. A white couple will often go into a showroom and be given a simple loan at the current market rate. In contrast, a Black couple that visits the same dealership with a similar credit rating will be given a higher-cost loan, which will result in increased charges of several hundred dollars on top of the loan’s term. In general, loans and credits are quite difficult to get and more costly for people of color, making it more difficult to cope with economic hardship.

Further Actions

Financial inclusivity may not be accomplished without concerted actions from the business, governmental, and social spheres. Banks and other private-sector stakeholders would make a significant impact effectively by eliminating geographic, administrative, and economic obstacles that prevent minority communities from gaining unrestricted access to banking goods and services. As legislator, controller, monitor, and creator of financial institutions, the public sector may propose and encourage ideas, including student loan overhaul and improved credit rating methods. Public agencies might also supervise and implement equality in financial inclusivity regulations, such as ensuring that mortgage brokers do not stereotype minority households moving to areas where there are majority white inhabitants.

Similarly, the social sector may assist in identifying and piloting new approaches that, if validated, might be scaled up. Considering the multitude of factors that contribute to financial marginalization, no one solution will result in complete financial inclusivity. Instead, unique and individual obstacles that keep underprivileged people out of the financial sector should be intelligently and permanently removed. As a result, this research proposes four concerted activities that the commercial, governmental, and social sectors may undertake to promote financial inclusivity:

Dismantling Regional and Affordability Barriers

Regions with racial minorities tend to have fewer bank outlets and higher banking costs than their white counterparts. A bank’s regional distribution should be examined regarding outlet locations and how it engages with local communities. There are several current principles and criteria for inexpensive banking, such as enabling $25 initial deposits, free internet and mobile offerings and restricting overdraft costs. Banking organizations may also embrace these practices. These initiatives may be tested systematically, advocated for, and piloted by social-sector agencies to reduce the impact of regionalization. For instance, can be efforts aimed at connecting low- and moderate-income black families with local financial institutions.

The public sector can support programs that incentivize organizations to expand their footprint in minority communities. In addition, new technology might help to alleviate geographic and financial restrictions. A growing number of online financial institutions are providing their consumers with a wide range of banking and investing options, many of which are free or have minimal costs. These include but are not limited to Aspiration Bank, N26, and Chime (Aria Florant et al., 2020). These services might assist in addressing the concerns of African Americans with smartphone or internet access but are now neglected by conventional banking institutions. The government can help these developing remedies by establishing a legislative framework that allows for the ethical implementation of electronically connected goods and services.

Diversification of the Financial System

Reducing the distrust felt by African-Americans in banking firms is a vital milestone in constructing the climate for the development of services that benefit black households. There are now 82% white loan officials and just 9% black loan officials, a significant disparity in the lending industry. Furthermore, just 7% of financial goods company directors and 2% of executive-level positions are held by people of color (Aria Florant et al., 2020). Given this underrepresentation, as well as historical precedence, it is possible that ethnic minorities may be seen as less desirable clients. Admittedly, nearly one in every three unbanked families cites a lack of faith in financial institutions as a justification for not opening a checking account (Aria Florant et al., 2020). Accordingly, when new capital goods and services are developed and choices concerning investments in particular areas are implemented, the opinions of diverse ethnic and racial groups must be considered. Making the financial services industry more diverse and fostering more egalitarian working conditions for racial minorities would make more financial products and services accessible to Black, Latino, and native Indian families.

Developing Creative, Inclusive Loan Decision-Making

Financial firms can use innovative credit rating methods that might increase the number of minority consumers able to get loans. New companies may use big data and behavioral economics to forecast a borrower’s creditworthiness in the long term. Consumers of color, who are particularly likely to have experienced exploitative lending as their first loan encounter and hence have more poor credit reports, can gain from this technique. Another effective credit-building initiative is the Mission Asset Fund’s Loan Circles Program, which involves participants giving cash to other participants of the group based on a cyclical system (Aria Florant et al., 2020). Credit reporting agencies are notified of reimbursements to assist members in building their credit records, and no fees or interest are charged. Black consumers might be better served by building consumer laboratories to investigate the interests and requirements of minority communities and utilizing this database to influence service creation, advertising, research, and policymaking in the community, commercial, and social sector sectors.

Financial Relief via Supportive Personnel Policies

In the end, firms across all industries can give the perks and services that their workers need to make better financial choices and solve medium-term money problems. Families in the United States suffer severe effects due to medium-term variations in their income and spending. Notably, the 50% of African American families with little or no liquid assets in comparison, white households account for 28% of all families (Aria Florant et al., 2020). Savings patterns and income leveling are supported by a variety of goods and programs available on the market nowadays. Nevertheless, banking and financial firms are in a privileged position to assist their people in this area.

An advanced wage access program, for instance, would enable workers to get their salaries sooner than the standard two or four week period for a nominal price. Even’s cooperation with Walmart serves as a good illustration of this strategy (Aria Florant et al., 2020). Workers will be more likely to take advantage of financial guidance and education given via the workplace if these offerings, goods, and prospects are clearly connected with consideration. In the long run, increased financial security for employees helps both the company and the company’s shareholders.

Conclusion

The analysis shows that banking in the United States has developed through time. More importantly, it shows that there has been a consistent goal throughout this evolution: to best represent business and society. However, this report has demonstrated that America’s banking sector has failed to fulfil its foundational goal of providing equitable access to loans and credits. Recent detailed information demonstrates that Black depositors and borrowers face much more significant barriers to banking products. This is seen in various products and services, such as deposits, mortgage loan credit, and commercial loans. Financial involvement for marginalized populations can have a significant impact on African Americans, the organizations that represent them, and the overall economy. The governmental, corporate, and social fields have a responsibility to perform in bringing about tangible improvements for marginalized communities, and they collaborate to achieve this goal. The existing state of affairs reinforces historical and contemporary inequities that disproportionately harm marginalized groups.

References

American Bankers Association. (2022). ABA history. Aba.com. Web.

American Bankers Association. (2022). Teach children to save. Aba.com. Web.

Aria Florant, Julien, J., Stewart, S., Yancy, N., & Wright, J. (2020). The case for accelerating financial inclusion in black communities. McKinsey & Company. Web.

Bayer, J. B., Ellison, N. B., Schoenebeck, S. Y., & Falk, E. B. (2016). Sharing the small moments: Ephemeral social interaction on Snapchat. Information, Communication & Society, 19(7), 956-977. Web.

Berry, M. (2013). Community Reinvestment Act of 1977. Federal Reserve History. Web.

Broady, K. E., McComas, M., & Amine Ouazad. (2021). An analysis of financial institutions in Black-majority communities: Black borrowers and depositors face considerable challenges in accessing banking services. Brookings; Brookings. Web.

Darity Jr, W., Hamilton, D., Paul, M., Aja, A., Price, A., Moore, A., & Chiopris, C. (2018). What we get wrong about closing the racial wealth gap. Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development, 1(1), 1-67. Web.

Faber, J. W., & Friedline, T. (2020). The racialized costs of “Traditional” banking in segregated America: Evidence from entry-level checking accounts. Race and Social Problems, 12(4), 344-361. Web.

FDIC. (2021). How America banks: Household use of banking and financial services, 2019 FDIC survey. Fdic.gov. Web.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). (2014). FDIC: Historical timeline. Fdic.gov. Web.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). (2022). Community banking research program. Fdic.gov. Web.

Henderson, L., Herring, C., Horton, H. D., & Thomas, M. (2015). Credit where credit is due? Race, gender, and discrimination in the credit scores of business startups. The Review of Black Political Economy, 42(4), 459–479. Web.

MacLeod, H,. D., Sumner, W., G., & Horn, A., E. (2018). A history of banking in all the leading nations: Great Britain. Creative Media Partners.

Rothbard, M. N. (2020). A history of money and banking in the United States: The colonial era to World War II. Auburn, Ala: Ludwig von Mises Institute

Sood, A., Speagle, W., & Ehrman-Solberg, K. (2019). Long shadow of racial discrimination: Evidence from housing covenants of Minneapolis. Available at SSRN 3468520. Web.

Sumner, W., G., (2018). History of banking in the United States: The bank war: Vol.2. LM

The Fed. (2018). Banking and Creditreport on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2018 – May 2019. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Web.

The Fed. The Fed report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2019 – May 2020. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Web.

Van, J. (2020). Reduce lending in low-income neighborhoods? Incredibly, the government has a plan that could help banks do that. The Hill. Web.

Waupsh, J. (2017). Bankruption: How community banking can survive fintech. Hoboken: Wiley.

Xaviant, H. (2016). The suppressed history of American Banking: How big banks fought Jackson, Killed Lincoln, and caused the Civil War. Bear & Company.