Introduction

Existing treatment guidelines for Hepatitis C formulated by specialist medical premises are primarily associated with people living in developed nations and cover only a particular population. The data collected is limited due to inappropriate reporting, treatment, and care for the Hepatitis C virus, as well as the asymptomatic nature of the virus. The research aims to provide recommendations on how a nursing practitioner should tackle treatment, screening, and care. Each of the topics discussed is complex and entails many dimensions. The paper will provide background and overview of the virus and statistical comparison of the virus in Florida and the US. Further, it will provide surveillance and reporting, Epidemiological analysis of hepatitis and screening guidelines are done, and plans to be outlined.

Background, Overview, and Significance of Hepatitis C

Hepatitis means liver inflammation that results from various causes such as abuse of alcohol, toxins, and prolonged use of certain drugs. However, hepatitis is mainly a result of a viral infection known as viral hepatitis. Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis Care are the most common forms of viral hepatitis. Other forms of the virus that are less encountered are Hepatitis D and E. The liver, which gets affected, is a critical organ within the human body with crucial functions of nutrient processing, filtration of blood, and fighting infections within the body. The main focus of this paper is Hepatitis C, a liver condition resulting from the Hepatitis C virus (HCV). The Hepatitis C virus has two categories, acute and chronic hepatitis C, based on the severity of the illness. Infection of acute Hepatitis C lasts roughly six months and disappears by itself for no apparent cause. On the other hand, chronic Hepatitis C is a continuation of acute hepatitis C if it fails to clear up, leading to serious health problems such as liver cancer, cirrhosis, and other liver-related diseases.

The most prevalent virus in the United States is hepatitis C virus. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 57500 persons are infected by acute hepatitis C annually. Still, only 4 136 actual cases were reported in 2019 (Centers for Disease Control, 2021). This is because most individuals, even those with chronic hepatitis, are unaware of having the virus and do not show any symptoms or feel sick. New hepatitis C cases reported are approximately 17000 yearly in the US. In Florida, the rate of reported hepatitis C virus infection in 2019 was 1025 cases, at a rate of 3.31 per 100 000 population, and decreased from the previous year, which had 1005 affected at a rate of 3.34 (CDC, 2019). CDC reports the virus to be most common in a certain age group in the US; these are the baby boomers (CDC, 2019). Baby boomers are people born between 1945 and 1965, and according to CDC, they are five times more likely to have hepatitis C virus than the rest of the age groups. The same applies to Florida, as the most affected group is the baby boomers. However, no clear statistics are provided, and further research will be considered in the plan.

Though very rare, hepatitis transmission can take place through sexual engagement. Research by CDC indicates that approximately 20 percent of persons who reported having had acute hepatitis tend to have been exposed to multiple partners (Spach, 2019). Likewise, persons injecting drugs risk getting hepatitis C, which usually accounts for around 60 percent of the cases. In general, 20-30 percent of individuals injecting medications get infected within the initial two years (Spach, 2019). Hepatitis C virus appears on a high via direct needle and syringe sharing. Most individuals suffering from acute hepatitis C are likelier to show no symptoms, though symptoms may occur within two to six months of being infected. Common signs may include joint pain, appetite loss, dark urine, jaundice, and abdominal pain. The same case applies to chronic hepatitis C, showing no symptoms. Still, the liver may be destroyed even if symptoms are lacking, and severe related liver diseases may occur.

Surveillance and Reporting

Hepatitis C surveillance is a crucial element of a detailed plan for preventing and controlling hepatitis C virus infection and other liver-related diseases. To attain the objectives of surveillance of hepatitis C, actions are required to identify individuals with acute and chronic HCV infections. Common surveillance and reporting guidelines for hepatitis C include case ascertainment and case reporting (CDC, 2021). It is a method of improving the completeness and timeliness of a report. It includes implementing laboratory reporting laws and ensuring sick people with signs and symptoms of acute hepatitis C virus are tested and reported appropriately. Lastly, ensuring patients with chronic hepatitis are tested and recorded effectively. Laboratory reporting rules state that rules and regulations should be implemented by all states that require laboratories to quickly make reports of test results that are positive antibodies to HCV (anti- HVC). Subsequently, case reporting involves a standardized collection of data on every case reported on viral hepatitis C. This should include data on age, race, sex, race, ethnicity, state, and county (CDC, 2021). Additionally, follow-ups ought to be repeated for all cases to check on 1) the presence of jaundice, 2) symptoms showing consistency with acute hepatitis C and the date it started, serologic tests, and results.

Epidemiological Analysis of Hepatitis C

Epidemiology analyzes how frequently the illness occurs in various groups and the reasons behind it to plan and prevent it. About 2.4 million individuals in the US suffer from chronic hepatitis C virus, but only half know about it (CDC, 2020). Though most predominant chronic hepatitis C infections are still more in those born between 1945 and 1965 (birth Cohort) because of unsafe medical procedures, there is an increasing alarm among adults younger than 40 due to drug injections. Despite the troubling trends witnessed in hepatitis C virus incidences, hepatitis C virus treatment has led to advancement in treatment and several highly successful and well-tolerated therapy schedules that have the possibility of positively affecting the current hepatitis C virus trajectory.

From the perspective of public health, predominant infections underdiagnoses and continuous incident infections together with curative treatment availability indicate that hepatitis C virus screening is needed. According to researcher Tatar et al. (2020), a decision analysis structure is employed in assessing the cost-effectiveness of a general screening of people above 18 years old and a targeted screening of persons injecting drugs for hepatitis C virus. Of the two, screening persons who inject drugs are cost-effective. The summary degree of interest is presented as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) by researchers and a representation of estimates per adde year an individual gains. These estimates are in line with current US CDC screening guidelines. Before this, CDC had recommended screening for people with known risk factors, which included drug use injections and all individuals born between 1945 and 1965.

To this end, in 2020, CDC updated the previous guidelines. Accordingly, it included a one-time screening for those above 18 years old except for places with 0.1 percent HCV prevalence (Schillie et al., 2020). CDC 2020 cost-effective analysis included adult screening with birth cohort screening with an assumption of hepatitis C virus of predominant of 0.84 percent ( ICER, $28,000), another general screening with assumed predominant of 2.6 percent and 0.29 percent for birth cohort and non-birth cohort, respectively (ICER, $11, 378) (Schillie et al., 2020). Likewise, a cost-effectiveness analysis of one-time screening for individuals between the ages of 20- 69 (hepatitis C virus prevalence assumed at 1.6 percent) compared to risk-based screening (ICER, $7900). An economic analysis enables theoretical comparisons of possible costs and results of public interventions within a given assumption stated by the structure of the model. Regarding all model-based analyses, their effectiveness relies on the approach and assumptions researchers employ.

Regarding the Hepatitis C virus, surveillance data is used to estimate fundamental epidemiologic measures. Medicine and health endorse utilize reference cases to establish a standard set of practices for comparison, for example, community versus health care view, summary results, and analytic horizon, though comparing the epidemiologic representation of a health factor can be challenging to compare. Basic epidemiologic measures of disease frequency and assumptions are the influential inputs in cost-effective approaches to interventions in public health. Precise, timely, and systematic estimates of predominance, occurrence, and mortality are critical in describing the disease level of population burden. Similarly, they are key measures for modeling possible interventions and policy results. For the Hepatitis C virus, surveillance data is used to estimate fundamental epidemiologic measures. However, the estimates are lacking mainly due to insufficient, under-sourced disease surveillance.

Though new hepatitis C virus reporting is carried out as one unit with the CDC nationwide notifiable illness surveillance system, the estimates are ineffective since most asymptomatic cases go unreported, there is a difference in laboratory requirements for testing, lacking surveillance resources, and inconsistency in the application of case definition. In correcting the problem, there is regular adjusting of published surveillance estimate and resulting model inputs by use of a single multiplication correction actor, which is outdated and oversimplified. Additionally, countrywide HCV predominance approximations mainly rely on data from large countrywide serosurveys with updates that depend on long delays between cycles of surveys. Dependable and timely data inputs are required to capture hepatitis C virus epidemic dynamics.

Screening and Guidelines for Hepatitis C

Screening for HCV infection determines the absence or presence of HCV antibodies in the blood system to signify if virus exposure happened. The results of HCV screening are reported as Invalid, Positive and negative. An invalid outcome shows that a repeat of the test should be conducted to get effective results, positive or reactive results show that the person currently has the infection or has been resolved through treatment or naturally. In contrast, negative or non-reactive outcomes indicate that a person has not been infected, the infection is still new, and HCV antibodies are still not developed.

A further test is required for positive cases to determine if the condition is chronic or acute. According to the American Association for the study of liver diseases, screening for HCV is recommended on blood components of blood recipients, blood recipients from an HCV-positive donor, present and past injection drug abusers, and people with conditions such as HIV hemophilia and children of HCV infected mothers. Individuals infected with HCV are mostly subjected to stigmatization and discrimination. Thus, guidelines are critical to incorporate basic human rights, including the right to confidentiality and informed decisions before screening and treatment are conducted (World Health Organization, 2018). The screening tool for this research is Alcohol Misuse Screening which entails several choice questions concerning how often or how much you consume alcohol and if an individual has any alcohol-related issues. It is sensitive and effective as there are no risks in taking the questionnaire.

Planning and Recommendations

HCV Infection Screening and Care

Many studies have been conducted to determine the best screening methods and care approaches for HCV. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses piloted by WHO examine the effectiveness of interventions for promoting HCV testing and care (Lange et al., 2017). For providing testing, WHO recommends HIV testing to be integrated in populations where both behaviors have high infection risk such as Persons Who Inject Drugs (PWID) and imprisoned people. According to WHO (2018), as part of the recommendations, nursing practitioners to provide HCV serology testing. Carty et al. (2022) conducted research that examined short behavioral interventions for alcohol reduction versus no behavioral intervention for persons infected by HCV. The results considered included reduced alcohol intake, mortality and life quality, and liver fibrosis (Carty et al., 2022). Screening for alcohol use plus counseling to control high and moderate alcohol intake levels, degree of cirrhosis, and liver fibrosis should be assessed as measures of care for persons infected with HCV. More importantly, WHO guides that people with HCV should it be stigmatized and discriminated.

Treatment

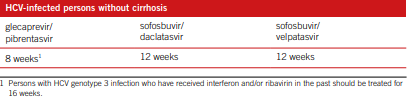

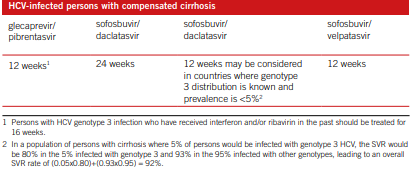

There are many ways of treating HCV and managing hepatitis C. meta- analysis, systematic reviews, as well as feasibility tests were conducted for supporting recommendations formulation process. In Cacoub et al., (2018), the result measures were SVR rates, mortality related to liver, decompensated liver illness, and life quality. From the analysis, recommendations include; treating with pegylated interfero and rivabin for chronic HCV, and treating with boceprevir for chronic with genotype 1. Those infected with HCV but with no cirrhosis and those with compensated cirrhosis, the treatment is as shown in the table 1 and 2 respectively (Cacoub et al. 2018).

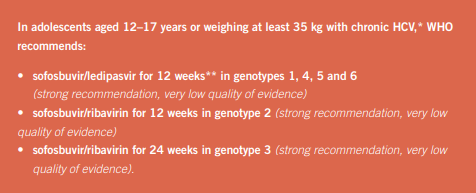

For children below 12 years, treatment should be differed until 12yrs, WHO recommendations is as shown in fig. 3 below (WHO, 2018).

Summary

The paper focused on Hepatitis C prevalence in the United States and statistics for those affected in Florida. The virus is the leading cause of liver-related illness and is most prevalent in baby boomers and persons who inject drugs. A significant concern about Hepatitis C is its asymptomatic nature. Through surveillance and reporting, the virus can be prevented and controlled through common surveillance and reporting guidelines for hepatitis C, which include case ascertainment and case reporting. Epidemiological Analysis provided Analysis of different groups affected by the Hepatitis C virus and financial and social Analysis provided. Cost-effectiveness ratios are used for economic Analysis, whereas reference cases are employed for social Analysis. Screening is conducted and depending on the state of the virus within the body, the answer can be positive or negative. In cases of invalid results, the test is repeated. Guidelines are critical to prevent stigmatization and discrimination. Finally, a plan is provided with recommendations for screening, care, and treatment is provided.

References

Cacoub, P., Desbois, A. C., Comarmond, C., & Saadoun, D. (2018). Impact of sustained virological response on the extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C: a meta-analysis. Gut, 67(11), 2025–2034.

Carty, P. G., Fawsitt, C. G., Gillespie, P., Harrington, P., O’Neill, M., Smith, S. M., Teljeur, C., & Ryan, M. (2022). Population-Based Testing for Undiagnosed Hepatitis C: A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations. Applied health economics and health policy, 20(2), 171–183.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Hepatitis C questions and answers for the public. CDC.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). 2019 Viral hepatitis surveillance report. CDC.

Lange, B., Cohn, J., Roberts, T., Camp, J., Chauffour, J., Gummadi, N., Ishizaki, A., Nagarathnam, A., Tuaillon, E., van de Perre, P., Pichler, C., Easterbrook, P., & Denkinger, C. M. (2017). Diagnostic accuracy of serological diagnosis of hepatitis C and B using dried blood spot samples (DBS): two systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC infectious diseases, 17(Suppl 1), 700.

Schillie, S., Wester, C., Osborne, M., Wesolowski, L., & Ryerson, A. B. (2020). CDC recommendations for Hepatitis C screening among adults — United States, 2020. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports, 69(2), 1–17.

Spach, D. H. (2022). HCV epidemiology in the United States. HCV Biology.

Tatar, M., Keeshin, S. W., Mailliard, M., & Wilson, F. A. (2020). Cost-effectiveness of universal and targeted Hepatitis C virus screening in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2015756.

World Health Organization. (2018). Guidelines for the care and treatment of persons diagnosed with chronic Hepatitis C infection. WHO.