Introduction

The curriculum defines what constitutes the graduates of a learning institution. It represents the diversity that makes up a school, college, institute, or university. Clearly elucidating the myriad pedagogical philosophies within the classroom and hands-on teaching, the curriculum helps in defining the strength, quality, and success of any learning or training institution. In order to keep up to speed with the dynamic nature of knowledge passage and training, the learning institution vests the power of curriculum development, updating, and review to the different faculties within the institution. Every faculty harbors the basic responsibility of developing a new course, updating existing programs, and reviewing teaching styles. All these functions aim at ensuring the outcome of education within such institutions proves worthy and valuable to the employment and job creation sector. From this dimension, the nursing faculty has to participate in designing an inclusive curriculum, which touches on all aspects of the sector.

Frightening aspects of change in curriculum development

Since curriculum development presents an alteration to the culture and normal practices within a system, there exists a need to ensure continuity to eliminate cases of fear among the implementing agencies and students. As Keating (2014) denotes, curriculum represents a formal plan of study with philosophical underpinnings, goals, missions, and guidelines necessary for the delivery of a specific educational or instructional program. In the informal setting, it encompasses the faculty, students, administrators, and consumer experiences. Developing an interactive phenomenon within such a setting becomes hectic, as it requires the interests and preferences of different parties. These differences coupled with the changes to culture within a given system offer great barriers in curriculum development. In a culture that previously relied on learner and learning outcomes in the nursing sector, for example, introducing a new curriculum with aspects of quality and safety, evidence-based practice, integration of telecommunication in service delivery, and translational science and research presents an uphill task since it presents new systems, imposes changes, and introduces different training and research modules. Understanding all these changes and ensuring proper continuity and progress from one curriculum to another, therefore, requires an independent system that takes into account the plight of all the persons involved in a given institution (Billings & Halstead, 2012). For this reason, faculties remain in place to ensure progressive review and update of institution curricula.

Factors affecting change process in curriculum development in the nursing sector

Demographic changes and increase in diversity

Population shifts in different parts of the world continue to revolutionize the structures, modes, and modules of influencing knowledge in nursing schools. With augmenting demand for clinical care and public health, standard lifespan continues to rise. This implies that persons with severe and chronic disorders continue to pose difficulties to the nursing fraternity. Therefore, curricula without an in-depth understanding of public health and clinical care become irrelevant as more focus shifts from universal care systems (Tanner, 2010). Equally, the increase in population diversities requires constant improvement of the nursing curricula. The occurrence of ailments and illnesses demand modifications in the mode of training in the nursing sector to take into account the various tenets and cultures that continue to arise in society. Increasing rates of morbidity, discrepancies in mortality rates, and an increase in population with access to care necessitate societal ills such as augmented violence and drug abuse. All these factors require adequate consideration on the learning programs in the nursing sector to ensure nurses remain privy to the changing physical and psychological health characteristics of the world population (Stanley & Dougherty, 2010). With some students taking classes on a part-time basis, educational programs require greater flexibility in reviewing and updating curricula as Stanley and Dougherty (2010) denote.

Technological advancements

Increased advancements in information, communication, and technology influence both health care delivery structures and nursing school training systems. Given the improvements in dispensation speed and volume, the introduction of interactive user interfaces, sophisticated and reliable systems, and the rise in the number of affordable computers and communication gadgets, the health care sector continues to undergo a drastic transformation. For example, Tanner (2010) argues that there exists an increasing use of telemedicine systems in the diagnosis and prescription of illness, thus reducing the conventional physical contact between patients and nurses. Similarly, the availability of the internet across many parts of the world enables the patients to acquire information previously confined within the health care practitioners’ dockets. Markedly, this ease of access to clinical data helps improve personal care management. Nanotechnology in the health care sector intends to come up with new procedures of clinical diagnosis and treatment using relatively cheap biosensors with capacities to detect different ailments. All these technological advancements require nurses to acquire computer literacy skills as well as advance their technological know-how. With the dynamism in the technological advancements, curriculum improvement and development keep the nurses within the latest technological systems to be at per with the emerging trends (Tanner, 2010).

Telecommunication advancement also influences the mode of learning within the nursing sector. For example, distance-learning modalities continue to link students from diverse backgrounds without physical contact. This helps in expanding the potential for accessing professional education as well as increasing the understanding of different nursing strategies in different parts of the world with minimal movements. In order to actualize online and distance learning, faculties require adequate understanding of the underlying factors and constraints that come with such investments. Likewise, with improved technologies, nursing schools enjoy the privilege of developing advanced preclinical simulation laboratories that improve critical thinking and skill acquisition among the trainees. Such laboratories come with computerized systems that ensure easy access to data and improved observation and communication systems, leading to advanced nursing research. In order to introduce such systems within a conventional nursing school system with minimal technological advancements, development of advanced curricula cognizant with the new technological systems becomes necessary.

Barriers to curriculum development in the nursing industry

Dynamism in the policy and regulatory systems

As the world develops and more technologies continue to come into play, legal and regulatory frameworks governing the nursing sector continue to change. The effects of dynamic federal and state health policies compromise the abilities of the faculties to keep reviewing and updating the nursing curricula. The complexity of the nursing field taking into account the medicine and economics aspects further jeopardize proper stakeholder engagement in policy formulations and curriculum development in this sector (Giddens & Brady, 2007). With individual consumers in the nursing sector focused on the quality of the services while the corporate players and nursing practitioners tilted towards economic survival, the desire for improved but cheap nursing systems becomes relatively difficult to achieve.

Constant need for a multifaceted education curriculum

Proficient and effective management of the multifaceted patients’ needs require an extensive array of skills and understanding. This implies that the nursing services continue to change form single nurse care systems to interdisciplinary management systems composed of professionals such as nurses, physicians, dentists, social workers, community health workers, and pharmacists among others (Ching-Kuei, Chapman, & Elder, 2011). Developing a multifaceted curriculum clearly delineating the roles of every health practitioner in a setting becomes difficult due to the number of faculties required for consultation. In essence, such a multifaceted system widens the scope of the curriculum further compromising the level of specialization within the nursing sector (Giddens & Brady, 2007).

Financial constraints

Continuous improvement of curriculum and inclusion of technologically advanced systems within the nursing schools require huge financial investments. Telemedicine, for example, requires constant supply of internet connectivity to ensure effective care and communication structures. Introducing the changes within a training school require high initial capital, which is beyond reach for many institutions. Similarly, the use of sophisticated technological tools in the training of nursing requires proper training and refresher course for tutors, lecturers, and professors handling the tools (Stanley & Dougherty, 2010). Developing a structure for such training and retraining of work force require high capital investments. This implies that any nursing school reviewing and updating its nursing curriculum must acquire huge financial capital.

Advantages of curriculum development in nursing schools

Flexible curricula reflect existing societal and health care trends. These ensure students take into account issues, research findings, and innovative practices within the contexts of the societal setting both at the local and global levels. Improved and flexible curriculum enables students to pick elective units that take into account their interests within the nursing course (Keating, 2014). Likewise, enhanced and improved curriculum provides student with opportunities to register course in a sequence that ensures commitment to areas of needs taking into account the emerging health issues.

In schools where faculties design, review, and update curricula in respect to the emerging health issues, there exist great emphasis on students’ value progress, mingling skills, originality, and desire for permanent learning careers, and commitment to better nursing functions and responsibilities. This sets a basis for continuous improvement among the professionals in the nursing sector leading to improved service delivery. Similarly, improved curriculum ensures nursing students get adequate time for self-reflection, value clarification, and analysis of components of a nursing professional within the class time. Such reservations ensure students understand patients’ expectations. Moreover, self-reflection enables faculties to understand students based on the cultural orientation, learning capabilities, and priorities, thereby developing systems for proper understanding of the entire students’ population (Billings & Halstead, 2012).

Improved curriculum offers learning capabilities that organize students to take responsibilities that represent the basics of quality nursing practice. Such basics include the roles of care providers, patient advocates, teachers, community health workers, change agents, and health coordinators among others. In understanding these basics, students develop adequate understanding and confidence required in executing the roles of the above personalities. Equally, such systems help students develop adequate listening, speaking, communication, and teamwork skills necessary in the nursing sector (Kantor, 2010). This helps in improving students’ abilities to achieve clinical competence as opposed to informal training systems without a proper curriculum. Evidence-based clinical practices help students acquire skills to tackle health issues with a wide range of cultural and racial setting. Likewise, with advanced curriculum, nursing students enjoy the options of specialized trainings leading to increased competencies. For instance, in many schools, students enjoy the options of focusing on specific components of nursing such as nursing educators, advanced practitioners, nursing administrators, and nursing consultants (Kalb, Conner-Von, Schipper, Watkins, & Yetter, 2012).

Tools necessary for curriculum development in nursing

Evaluation benchmarks

This offers the nursing institution a bearing for comparing its own curriculum against those of the other players in the sector. For example, a nursing school should consider pass rate on an accredited examination. Similarly, the schools need to assess the costs of the program, admission criteria, accreditation status, alumni employment rates, and community reputation rates (Keating, 2014). Taking into account all these factors provides a benchmark for improvement and updating of curriculum.

Qualification of the faculty members

Productivity of the faculty members hold direct bearing on the productivity of nursing school alumni. Developing an updated and competitive nursing curriculum requires employment of experienced and highly qualified faculty members. Recruitment of such members must consider individual records of accomplishment, publication history, and research records (Keating, 2014).

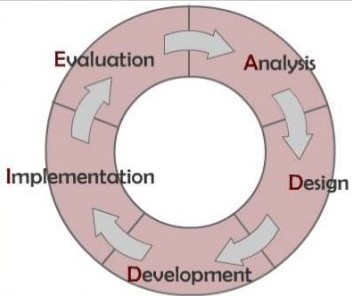

Phases of Curriculum Development

Analysis and Design phase

In the analysis phase, tutors clarify instructional problem to students with adequate establishment of goals, objectives, missions, and visions of the course in question. Similarly, it is at this stage that the tutors define the expected learning environment to the students. This stage enables the students to appreciate the different skills and knowledge existent among their fellow students, thus creating a bonding structure necessary for long-term coexistence. On the other hand, in the design phase, tutors and students go through thorough analysis of the learning objectives, assessment instruments, expected exercises, and course outlines (Iwasiw & Goldenberg, 2015). Likewise, the class develops subject matter analysis, lesson plans, and channels of communication. This phase requires a systematic and specific attention into finer details in order to develop efficient curriculum execution plan.

Development and Implementation phase

Upon the completion of design phase, development phase tasks the designers to develop and assemble content assets necessary for realization of the course schedule. Development phase requires concrete and objective engagement between the tutors and the students since it present the talents and interest identification stage. The implementation phase has a direct bearing on the amount of time investment in the learning settings since it covers the methods of testing and evaluation of performances (Iwasiw & Goldenberg, 2015).

Evaluation phase

Even though this stage overlaps across the entire phases of the curriculum development, it helps in the formative and summative assessment of all the aspects in the curriculum to develop an in depth understanding of the projects. This stage assesses the success, complacency, and efficiency of the implemented curriculum. Besides, it assesses the ability of the set out style of training to respond to students’ need in respect to the instructors’ abilities (Kalb et al., 2010).

Conclusion

Curriculum development remains the basic responsibility of faculty members in nursing schools. In order to keep up with the emerging trends in the health sector as well as the rising needs for specialized health care services, faculty members require effective curriculum development skills relevant to the societal desires. Periodic reviewing and updating of existing nursing curriculum helps nursing schools respond to changes in the society, health care needs of the rising population, and service delivery trends. In addition, it offers future nursing administrators to develop adequate leadership skills necessary for organizing and executing the evaluation and assessment activities.

References

Billings, D. M. & Halstead, J. A. (2012). Teaching in Nursing. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

Ching-Kuei, C., Chapman, H., & Elder, R. (2011). Overcoming Challenges to Collaboration: Nurse Educators’ Experiences in Curriculum Change. Journal of Nursing Education, 50(1), 27-33.

Giddens, J. F., & Brady, D. P. (2007). Rescuing Nursing Education from Content Saturation: The Case for a Concept-Based Curriculum. Journal of Nursing Education 46(2), 65-69.

Iwasiw, C. L., & Goldenberg, D. (2015). Curriculum Development in Nursing Education. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Kalb, K. A., Conner-Von, S. K., Schipper, L. M., Watkins, A.K., & Yetter, D. ( 2012). Educating Leaders in Nursing: Faculty Perspectives. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 9(1), 1-13.

Kantor, S. A. (2010). Pedagogical Change in Nursing Education: One Instructor’s Experience. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(7), 414-417.

Keating, S.B. (2014). Curriculum Development and Evaluation in Nursing. New York: USA, McNaughton & Gunn Printers.

Stanley, M.J C., & Dougherty, J. P. (2010). Nursing Education Model. A Paradigm Shift in Nursing Education: A New Model. Nursing Education Perspectives, 31(6), 378-80.

Tanner, C. A. (2010). Transforming Pre-licensure Nursing Education: Preparing the New Nurse to Meet Emerging Health Care Needs. Nursing Education Perspectives, 31(6), 347-53.