Abstract

Environmental studies provide learners with an opportunity to advance their knowledge of how organisms interact with their environment. The study enhances one’s knowledge of how the interaction shapes the species of organisms. Some species have gone extinct, while others have undergone significant changes to fit in the new environment. A clear understanding of how different primate forms evolved enables one to find our Place in the primate family tree.

Paleocene Plesiadapiforms

Purgatorius (Early Paleocene, North America)

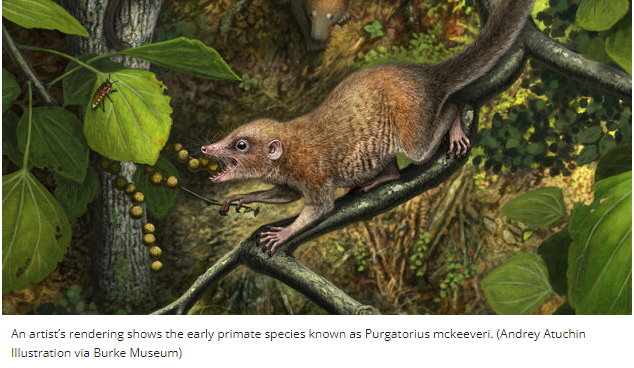

The Purgatorius is believed to be the earliest representative of a primate. Being a genus of the seven extinct eutherian species, the Purgatorius dated around 66 million years ago. The collection of the first remains of Purgatorius was in 1965 at the currently known Eastern Montana’s Tullock Formation. The species include the Purgatorius ceratops and the Purgatorius unio, whose fossils were precisely found at Purgatory Hill, hence its name. The species fossils have also been discovered in McCone County around the lower Paleocene Hell Creek Formation and the Harbicht hill. A further collection of the remains of the Purgatorius has been reported in the Ravenscrag Formation, Leptictids, and early Paleocene Bug Creek Group.

The Purgatorius existed shortly after the demise of the dinosaurs when plants began to bear fruits. Scientific revelations of the diet of the Purgatorius indicate that the primate consumed fruits, insects, and flowers. This revelation reveals that the area had plants and trees, which supported the availability of fruits and food for insects. The details regarding the brain of Purgatorius are not widely known due to the high crash impact on the remains. However, the primate is believed to have a primitive brain characterized with anteriorly expanded, large and conjoined olfactory bulbs with a notably larger hindbrain compared to the cerebrum.

The Lissencephalic cerebrum of the early primate was also found to be smaller. Due to the crushing impact, the Encephalization Quotient (EQ) could not be ascertained, but it is estimated to be smaller than the preceding primates. These primates’ primary habitat was North America. The primates’ locomotive patterns include walking vertically using their four legs, while no research has been made available for the sensory system of the species.

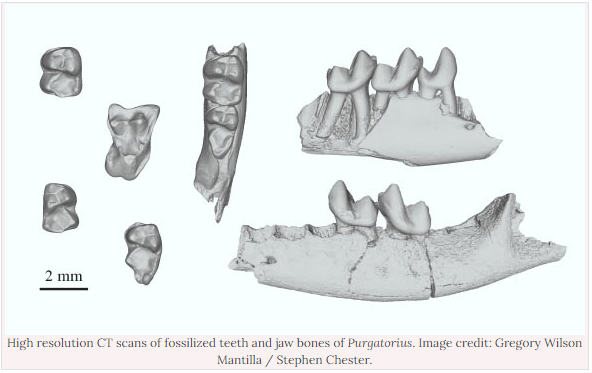

The primate teeth entail topotypic lower molars, with the first and second molars having the same length. The dentition of the species has been determined to be more primitive than those of any other known living and fossil primates. Recent findings indicate that the Purgatorius had a flexible ankle. The musculus flexor fibularis of the species enables digital flexion and plantarflexion within the foot, which is essential for grasping.

Plesiadapis Paleocene

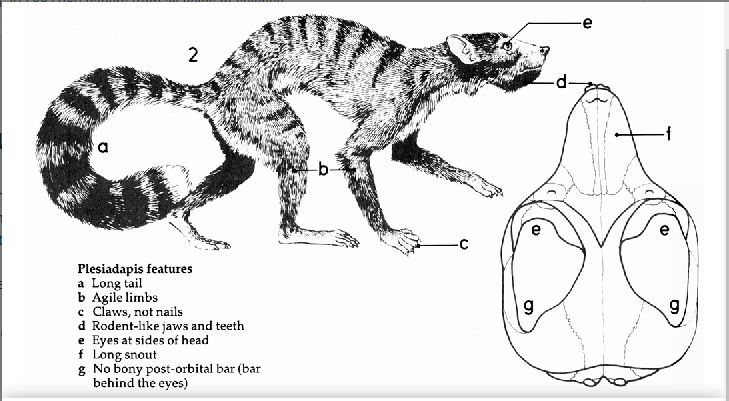

The Plesiadapis represents one of the oldest mammals with primate-like features around 55-60 million years ago. The species is named after its three cusps which are located within its upper incisors. The remains of the Plesiadapis have been discovered in the late Paleocene and central continental areas in North America and Europe. In North America, the Plesiadapis existed during the Clarkforkian and Tiffani lan mammals, where its fossils were recovered. The species lived longer in Europe, where it existed during the earlier years of the Ypresian geological age. The majority of the remains of this species comprise isolated teeth, postcranial skeleton, and maxillae. Some of the dating techniques commonly used by scientists in dating the Plesiadapis fossils include Mammalian Biostratigraphy and Geochronology.

Plesiadapis being squirrel-like mammals, majority of its body features like claws, fingers, and toes indicate that they lived in areas with high forest cover. These features were vital in the locomotion of the mammal, climbing, grasping, and clinging on trees. Plesiadapis is an archaic primate meaning the species shares some standard features with the primates while lacking other features. Some of these common features involve the molar teeth.

The locomotion pattern has ranged from subterranean bouncing to quasi sensoriality and tree – bouncing, and claw climbing. The diet of Plesiadapis is still debatable though scientists believe the mammal lived in trees in the forests. Having emanated from carnivorous/insectivorous lineage, changes within the primates that permitted grinding and crushing changed the diet to omnivore and herbivore diets. Scientists reveal that the Plesiadapis had a flexible body, bushy tail, with a snout-like face. There is a gap between the premolars and the incisors of the primate, while the dental formula comprises two incisors, one canine, three premolars, and three molars (2.1.3.3).

Plesiadapis, just like other earlier primates, had a small brain size compared to its body size. The brain of the mammal is estimated to weigh around 5g. The mammal’s skull has been found to comprise the braincase, rostrum, basicranium, and lower and upper dentition. The axial skeleton of the primate includes six lumbar vertebrae, 12 thoracic and five cervical vertebrae. No data has been recorded on the jaw muscles, thorax, and shoulders of the species.

Eocene Euprimates

Teilhardina (Early Eocene) Asia, Europe, North America

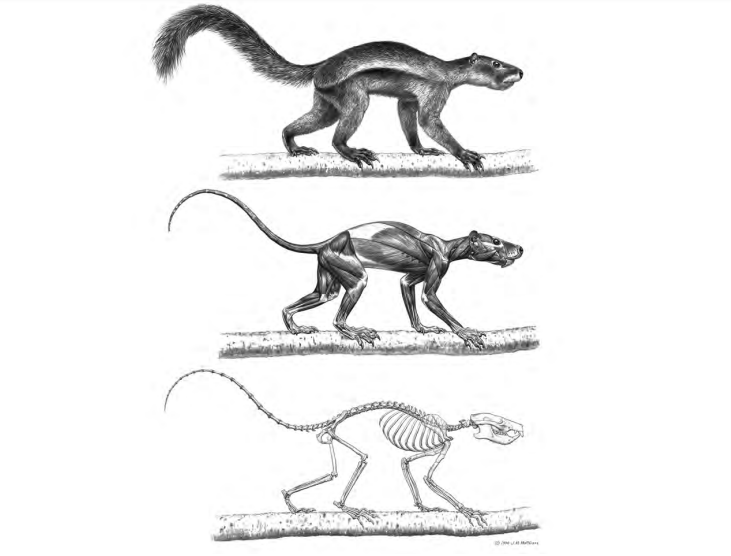

Euprimates refer to a group of primates that are considered primates of modern aspects. The teilhardina can be understood as a small creature resembling the modern-day bushbaby with a long tail, strong back legs, and big eyes. The remains of Euprimates were first recorded during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PEtM). Teilhardina is characterized as a tiny fur-covered creator that spent most of their time on trees. The primate is reported to have a longer tail compared to the size of the body and a long and slender tail. The primate has been identified as one of the oldest and allegedly most primitive creatures amongst the omohyoid. Different species of teilhardina have been discovered in North America, Asia, and Europe.

The species was named after French Jesuit philosopher and paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin after its discovery 56 million years ago. One of the methods used for dating the fossils includes the use of carbon isotope stratigraphy.

Body features recorded for the primate give knowledge on the environment in which the primate operated. Features such as lateral hand positions indicate grasps on trees. Analysis of the hind limb of the primate shows foot inversion abilities, arboreal lifestyle, climbing, leaping and grasping. These features mean that the primate lived in an area associated with trees and dry land.

The recording of the majority of the species of teilhardina bears only jaw fragments and teeth. However, the species teilhardina Asiatica takes a complete skull restoration. The skull indicates that this species had relatively more nominal orbits in line with the daily activity pattern—the species t. Belgica wa found to bear various ankle bones, distal femur, finger bones, and a proximal metatarsal holding the big toe. These features reveal that the creature was arboreal as the hindlimb was adapted for grasping and leaping. The primates are reported to adopt a hunting-like behavior where they utilize their elongated arms to pin prey to the ground.

A key finding reported amongst the teilhardina is that the primate experienced weaker molar shearing crests than the latter primates (Schultz et al. 1-45). This situation led to a mixed diet for the primate, which comprised insects and fruits. The rodent-like primates walked using four dry-land legs and could use their back legs to jump on tress. The habitat of the primate was on trees, where it also built its nest. No data has been recorded on the thorax size sensory system jaw muscle, and shoulders.

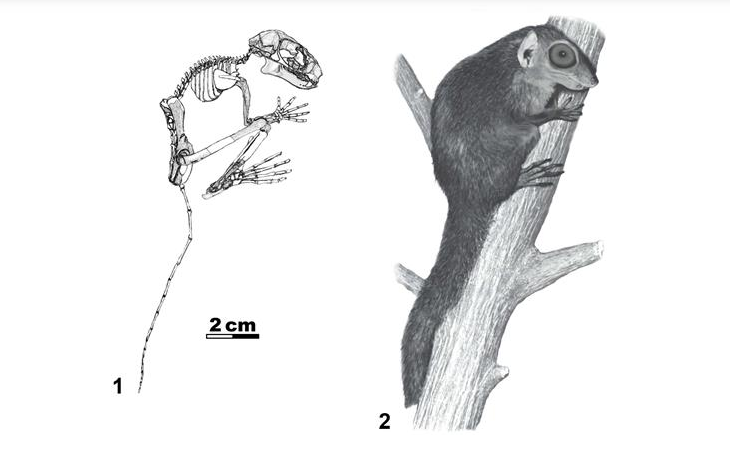

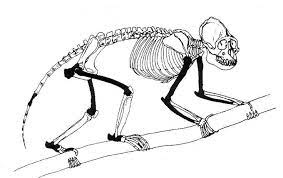

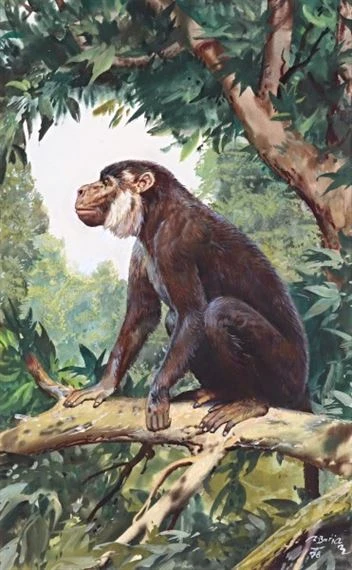

Skeleton Reconstruction and Photo of the Teilhardina

Darwinius

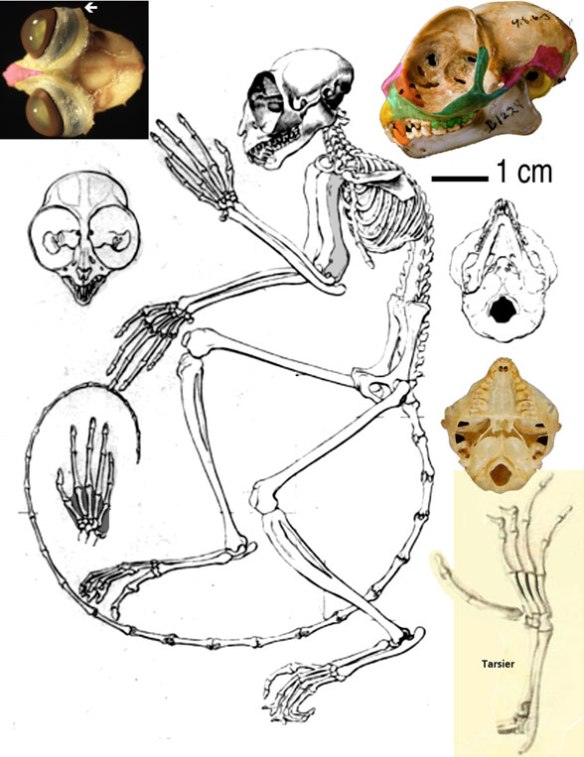

The Darwinius represent a genus from a group of basal strepsirrhine primates that lived during the Eocene period. The only known species of the genus is the Darwinius masillae, whose remains were collected 47 million years ago. Scientists used chronostratigraphy to date the fossil from the rock stages at a quarry in Messel, southeast Frankfurt, Germany. The Darwinius masillae is one of the complete primate fossils collected.

The Darwinius masillae, nicknamed Ida, is one of the most controversial fossils as it is presented as the missing link between prosimian and anthropoid primates. Some scientists believe the form was a prominent evolutionary form interlinking the primitive primates with the prosimian and simian genealogy. A classification of the fossil placed it to a period when primates divided two different clades.

Some developed to prosimians while others developed to anthropoid monkeys and finally apes. It is also worth noting that other scientists have disagreed with the findings that Darwinius is the missing link between primitive primates and anthropoids. These scientists claim that the Darwinius was indeed a strepsirrhine. This group includes primates like the lorises, lemurs, and galagos. This classification eliminates Darwinius from being the direct ancestors of humans but rather an ancestor to the tooth-combed prosimians.

The cat-sized primate is estimated to have been around 58 cm from the nose to the tail. The fossil collected indicates that the Darwinius possessed primate-like features, including nails instead of claws and opposable thumbs that comprehend the grasping hands on the lemur-like skeleton. The handmade features are suitable for the Darwinius to have an efficient grip crucial for climbing and gathering fruits. The fossil’s stomach content reveals that the last meals that Ida had taken were leaves and fruit, thereby indicating the rich in fruit-bearing trees and vegetation. The Darwinius fossil also revealed shorter limbs and flexible arms. On the contrary, the fossil recovered was missing crucial features commonly identified in lemurs. The fossil lacked a blended row of teeth, a grooming claw within its feet, and a toothcomb within its bottom jaw.

The commotion of the Darwinius walked using its four legs. The primitive thorax is shorter than the legs. The primitive sensory system is made up of eyes, ears, and tongues. The primitive also could detect danger, and its brain was also used as a sense organ. Data on the shoulder and jaw muscle of the species has not been found.

Lemurs (Lemuroids) Of Madagascar

Aye aye (extant, Madagascar)

The Aye-aye, which lives in the rainforests of Madagascar, is mainly a rare species in the Animalia kingdom and the sole member of its family classification. Lemurs Island in Madagascar with the fossils first discovered in 1833. The aye-aye runs and walks in the forest’s trees and mostly likes to operate during the night. The unique aye’s trait is its exceedingly tiny middle finger, which it uses to tap on trees to detect grubs beneath the bark. The aye-aye uses percussive foraging to identify open spots in the trees by listening for echoes. When an individual discovers a hollow area of a tree, it gnaws through the bark and uses its fingertips to search for grubs and insects within the tree.

The middle finger of the forearm is distinguished from the others by its somewhat birdlike structure and increased joint flexibility. Though the fourth finger is the longest on the hand, the middle finger has unparalleled reach. The metacarpal works as an extension base; the web of skin between the second and fourth fingers has been inhibited. Free fingertip movement in the middle finger is yet another notable trait of the aye-hand aye’s specialty. The tapping finger moves much quicker than the other fingers when the aye-aye taps the wood with its middle finger as it glides along a wood surface. Videotapes of aye-aye palms exploring cavities revealed the movement of the middle digit inside the crater was significantly more significant than the movement of the hand and fingers outside the hole.

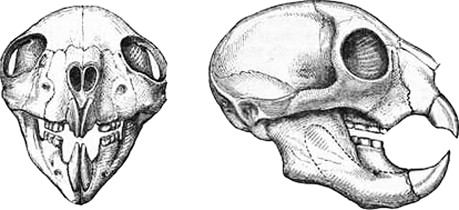

Aye-ayes both have a distinct skull and teeth. Unlike all the other strepsirrhines, they lack a toothcomb. 1/1, 0/0, 1/0, 3/3 = 18 is the adult dental formula. The deciduous dentition includes extra upper and lower incisors, premolars, and an upper canine. The adult bottom teeth are massively enormous and constantly expanding. Only the anterior surface of the Aye’s teeth has enamel; therefore, they self-sharpen as they wear just like rodent incisors. A diastema exists posterior to the incisors while the cheek teeth have flattened cusps and are inconspicuous. The skulls have been rounded, and the face area has been shortened.

The mammal weighs around 2.5 kilos, with females weighing somewhat less than males by approximately 100 grams on average. Aside from weight and male and female genitalia, there is no sexually phenotypic variation in aye-ayes. Both genders have a 44-53 cm tail and face length of 30-37 cm, while the neck of an adult bears black or dark brown fur with white guard hairs. The tail of an aye-aye is bushy and squirrel-like in appearance. The Aye- aye’s face is rodent-like, with brilliant, beady, luminous eyes in the form of raccoons. It has pretty big upper teeth that continue to develop throughout its life. Aye-aye walked on four legs, and it mainly live-in forests in Madagascar. The primate had large ears, an ever-growing incisor, and an extended middle finger which formed the sensory system. Data on the jaw muscle, thorax, and shoulders of the species has not been recorded.

Indri (extant, Madagascar)

The first skull in Madagascar was discovered in 282 BC. The dating method used for the fossil was radiocarbon dating. The Indri belongs to a type of lemur that can only be found on the remote island of Madagascar. The Indri, like all other Lemurs, originated from little creatures who arrived on the island from Africa some 50 million years ago. The Indri is locally referred to as the babakoto, meaning “little father” or “forefather of mankind.” Indris are the most prominent existing Lemur subspecies, with some individuals reaching about a meter in height. On the other hand, the typical Indri is between 60 and 80 cm tall, with a 5cm tail.

The molars have four quadritubercular teeth. The paracone and metacone produce sharp-edged vertical facets that flank V-shaped embrasures between the molars and interlopes on the occlusal surfaces. The protoconid and hypoconid are joined on the lower molars by crests that produce a zigzag shearing surface.

The Indri has a rich coat of silky black fur with various white spots according to the location. Their toes and fingers are exquisite and ideal for grabbing, and their large hind legs help them leap 10 meters between towering forest trees. The glowing eyes of the Indri face forward to help them evaluate distance before jumping. The Indri, together with the diademed sifaka, is a giant primate presently alive. Each species typically measures around 6.5 kilograms but weighs as much as 9.0 kg, 9.5 kg, and maybe up to 15 kg. The primate has a face range of 64–72 cm and may reach over 120 cm (4 ft), including its limbs when it completely stretches.

Indri lemurs are known as vertical creepers and tree swarmers. The nearly tailless Indri runs from tree to branch up to 30 feet with a packed spring-like action made feasible by the breadth and power of its back legs. Indri locomote using four legs on dry land and the legs are also used in climbing of trees. When they are not leaping or climbing, the primates hold to a vertical support, the stance depicted by our flexible skull’s mount. Indri males and females have an insignificant difference in their physical structure but only in their sexual organs. A female takes about two to three months to give birth. A young indri has grey hair and turns black as it ages at around two years old. Main sensory organs include mouth eyes nose and its ability to have a very strong eye sight. No data on thorax and shoulders of the species has been recorded.

Early Anthropoids

Aegyptopithecus zeuxis (30 Ma, Fayum, Egypt)

Indri lemurs are known as vertical creepers and tree swarmers. The nearly tailless Indri runs from tree to branch up to 30 feet with a packed spring-like action made feasible by the breadth and power of its back legs. Indri locomotion is through its four legs on dry land, and the legs are also used in climbing trees. When they are not leaping or climbing, the primates hold to a vertical support, the stance depicted by our flexible skull’s mount. Indri males and females have an insignificant difference in their physical structure but only in their sexual organs. A female takes about two to three months to give birth. A young indri has grey hair and turns black as it ages at around two years old. The primary sensory organs include the mouth, eyes, nose, and its ability to have powerful eyesight. No data on the thorax and shoulders of the species has been recorded.

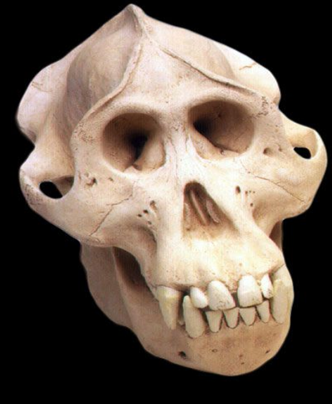

The cutting edges engaged in the buccal phase surround basins so that material is chopped into pieces. These pieces are retained and ground during the lingual phase, resulting in a compartmentalizing shear adaptation in the molars. Researchers have found the canines of this species as hermaphroditic, while the ascending mandible ramus of this species is relatively large. As the orbits are dorsally oriented and small, the primate was considered a diurnal animal. In this species, there has been some continued usage contraction. Aegyptopitheccus Zeuxis was suspected of hermaphroditic, indicated by tooth size, craniofacial shape, brain size, and body mass.

Due to the sexual dimorphism of A. Zeuxis, the social organization is assumed to have been polygynous, with solid competitors for females. The cranial size of this specimen was determined to be 14.63 cm3, whereas a reanalysis of a male endocast estimated a cranial capacity of 21.8 cm3. These figures disprove prior estimates of around 30 cm3. These results result in a male to the female embryological ratio of about 1.5, showing that A. Zeuxis is a dimorphic subspecies.

Based on the characteristics of the jaw structure, the spices may feed of handy things like tree trunks. Male and female body sizes are similar and their dental alignment, especially in premolars and canine. It is approximated that the male had more weight than the female, while the skull shows the primitive adaptation and how the head was structured. Research shows that the primate had two sharp canines teethes. The animal, which was monkey-like, walked on for legs and mostly lived on trees. Data on the thorax and shoulders of the species is yet to be recorded.

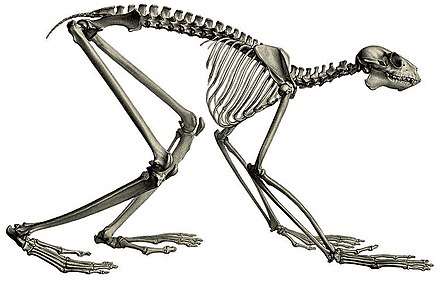

Proconsul (or Ekembo) heseloni (18-20 Ma, East Africa)

The Proconsul (or Ekembo) heseloni was estimated to have lived around 17- to 20-million-years during the Miocene period. The fossil deposits of these primates were found in Rusinga Island and Mfangano Island in Lake Victoria, specifically near Kenya’s old Kisingiri volcano. The word Ekembo comes from the Suba language and means “ape.” The dental and mandibular anatomy of Ekembo distinguishes it from other early Miocene catarrhines. Ekembo’s molars are rounder or bunodont than Proconsul’s, and its canine teeth taper to a tip, whereas Proconsul is more “blade-like.” The method used for dating is relative dating, in which the fossils were dated by dating the rocks where the fossils were found. Carbon dating was used to date the fossils as carbon isotopes were present in their teeth as herbivorous.

Non-forest forms of woodland are some of the settings connected with proconsulid species. The largest proconsulid species weigh around 28–80 kg and are more significant than most arboreal monkeys. The ability of these primates to travel in trees would have been limited, as observed in terrestrial baboons today. As a result, reports indicate, the species were partially terrestrial. Early Miocene settings associated with proconsulids were somewhat seasonal, according to a mixture containing simulations with Ekombo being believed to have lived in the savanna and had a different diet.

The Proconsul (or Ekembo) heseloni has been indicated to possess forest-dwelling adaptations in the upper arm as the humerus head’s higher torsion. Compared to other primates, the primate lacked a shaft curvature and a trailing edge. The radius neck is somewhat expanded in the forearm, the ulna’s spinous structure is lengthened, and the thoracic index is less than those in other remaining monkeys and apes. The patella is big, flat, and thin, comparable to that of chimps but differs from that of monkeys, which is thicker. Other than their temporary structure, the other difference is that male canines were different from females.

The Proconsul’s four legs and two arms help climb trees. They also lived as a group or as a family where there was the male and the female. Some of the adaptions recorded on these species are small arms than legs. They were bipedal, and they lived on trees just like the monkeys. Their sensory organs resembled that of human beings, like the nose, ears, and mouth. The species data on jaw muscle, thorax, and shoulders are yet to be recorded.

Extant Hominoids

Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus)

Orangutans are giant apes that live in the Indonesian and Malaysian jungles. Currently, they are exclusively found in Borneo Island, although they once roamed Southeast Asia and South China during the Pleistocene period. The method of dating used by scientists was carbon dating since they were herbivorous; thereby, scientists could trace the carbon in their teeth. The Bornean orangutan can be found in tropical and subtropical wet broadleaf woodland as well as hilly places.

Bornean orangutans live in lowland largest and most significant, freshwater and peat mangrove swamps. The majority of their diet comprises figs, durians, pineapple, mulberries, ripe mangoes, branches, nuts, insects, termites, and bark. Females achieve sexual maturity at roughly 10-15 years of age and, depending on the quality of the environment, give birth to a single offspring every 6-8 years. Researchers have confirmed nest-building activity among the Bornean orangutans. Nests are designed to be used at night or during the day while the young orangutans learn by watching their mothers make nests. Orangutan hands feature four long fingers but a somewhat smaller opposable figure, allowing them to maintain a firm grasp on branches as they go high in the trees. Orangutans’ feet contain four long fingers and a prehensile big toe, allowing them to grab objects firmly with both their arms through using the palms of their legs.

Physical masses of Bornean orangutan largely overlap with the far more giant Hominids; however, the latter is much more varied in stature. In comparison, the Sumatran orangutan is comparable in size but generally weighs somewhat less. Male averaged 75 kg (165 lb) and a length of 1.2–1.7 m (3.9–5.6 ft). On the other hand, females mean 38.5 kilograms, with a 30–50 kg weight range and a length of 1–1.2 m. The ape uses its two legs and two arms to climb trees and also to walk. The sensory organs are similar to apes as they use ears, eyes, mouth, hands, and nose as their primary sensory organs. Data on jaw muscle, thorax, and shoulders of the species have not yet been entered.

Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes)

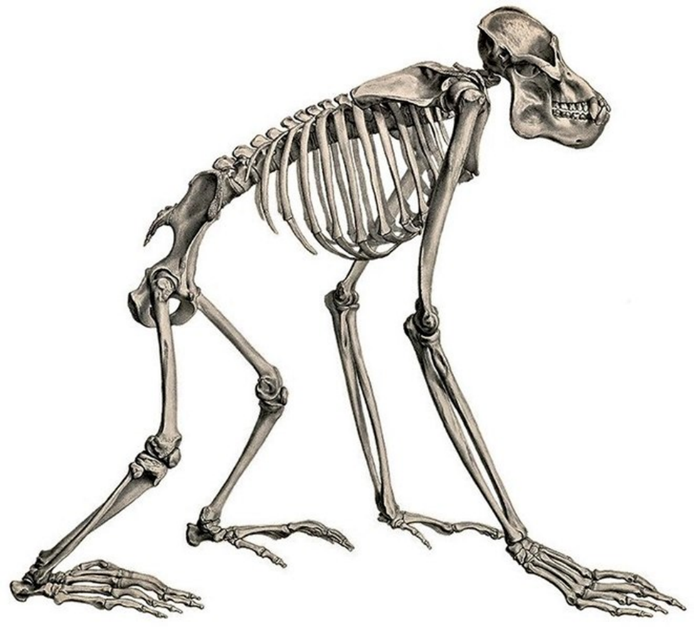

Chimpanzees are baboon-like creatures that live in the wilderness. They have different characteristics, and they closely resemble that of baboons. Pan fossils were not described until 2005, despite a massive number of Homo fossil discoveries. Although chimpanzee communities in African countries do not coincide with critical human fossils sites in East Africa, chimpanzee fossils have recently been discovered in Kenya. This discovery suggests that both humans and members of the Pan clade lived in the East African Rift Valley throughout the Middle Pleistocene.

The chimpanzee is covered with thick black fur but has a naked face, fingertips, feet, palms, and soles of the feet. The primate is big and tough, measuring 40–70 kg for males and 27–50 kg for females, and 120–150 cm tall. The mammal has an eight-month reproductive cycle while the baby is separated from its mother at around three years of age but typically retains a strong bond. The chimpanzee is a highly adaptive animal found in a wide range of environments comprising of; dry savannah, temperate jungle, coniferous forests, wetland woods, and a dry wooded mosaic. The chimps in Gombe prefer they confined an evergreen and deciduous forests. At Bossou, the chimps live in a multilevel intermediate forested area that arose due to shifting agricultural and primary forest and grassland.

The chimpanzee is a frugivorous omnivore, and berries are its preferred meal, although it also consumes leaves and leaf buds, seeds, blooms, stems, pith, wood, and resin. Chimpanzees walk quadrupedally using a technique called knuckle-walking. Chimpanzees have 1.5 times the physical strength of humans due to a more significant percentage of rapid burst muscle adapted explicitly for hanging on trees. Their sensory organs are close to that of human beings with five sensory organs. Great apes have several anatomical characteristics in the shoulder and upper thorax that have been connected to orthograde arborealism in the past. The figure of the primate is adapted for impact resistance throughout terrestriality. The chimpanzee has strong jaw muscles to help them eat as they are omnivorous.

Early Hominins

Australopithecus afarensis

Australopithecus was an endangered australopithecine species that flourished in East Africa during the Pliocene epoch around 3.9–2.9 million years ago. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but significant fossil discoveries occurred only until the 1970s. The method of biostratigraphy, a relative dating method, was utilized in southern Africa to date the bones of Au. Africanus. The lack of volcanoes in the area necessitated a radiometric dating technique, such as 40Ar/39Ar, that could not be employed on the sedimentary levels.

Australopithecus afarensis has a long face and a fine brow ridge, and its jaw is jutted outwards while the jawbone is enormously comparable to gorillas. The live size of australopithecines is being contested, with explanations for and against male and female size differences. The fossil Lucy was about 105 cm tall and weighed 25–37kg, yet she was petite for her species. On the other hand, Australopithecines assumed the guy was projected to be 165 cm and weigh 45 kg. Australopithecines’ apparent size difference between men and women might be due to sampling bias.

The face of A. Afarensis was tall, with a subtle brow crest and distinctive properties like the jaw that jutted outwards. one of the giant skulls is around the size of a female chimpanzee skull. The ridges resemble chimpanzee emblems and female gorilla crests. The incisors of A. Afarensis are narrower than those of earlier hominins. The canines are smaller and lack the honing mechanism that keeps them sharp. The premolars of the species are molar-shaped, while the molars appear taller. Australopithecus molars are broad, flat, and have strong veneer, making them suitable for breaking frozen and brittle meals. The primate adapted through having fur on their body that acted as a preventive measure towards the coldness of the Ethiopian region.

A. Afarensis specimens appear to have a broad variability, often interpreted as considerable sex differences, with males being much more extensive than females. Henry McHenry, an American anthropologist, approximated body size in 1991 by measuring the joint diameters of the leg bones and scaling down a person to fit that size. These measurements resulted in a putative male standing at 151 cm (4 ft 11 in), while Lucy stood 105 cm (3 ft 5 in).

In 1992, the scientists calculated the male weight, weighing around 44.6 kg and females 29.3 kg. The primates were considered to use two legs to walk and walk upright like the modern-day man. The australopith pelvis is platypelloid, with a more oval shape and a broader space between the hip sockets. Lucy’s pelvic entrance is 132 mm overall, nearly the same as a modern female human, despite her tiny size. These were most likely modifications to compensate for the slim legs by limiting how far the center of gravity dropped while walking upright—the sensory organs were like that of a human being.

Australopithecus Sediba (1.9 mya, Malapa, South Africa)

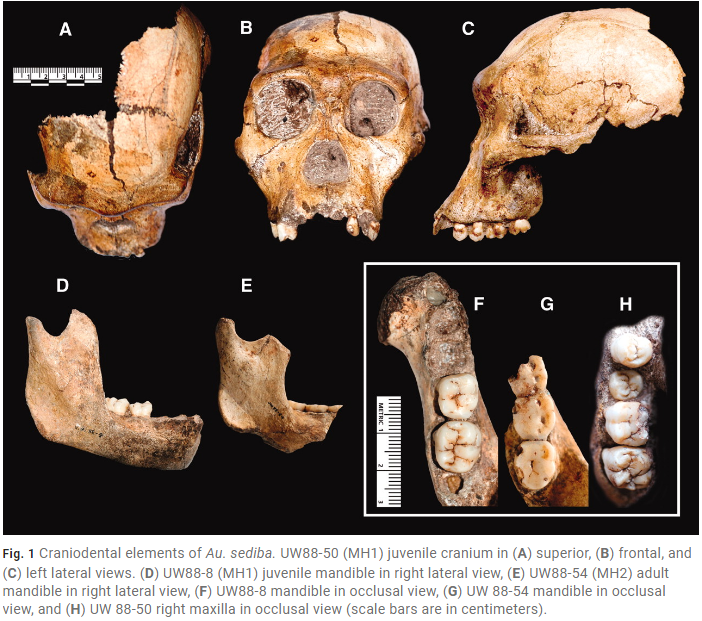

Australopithecus sediba is an extinct australopithecine species discovered in South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind, Malapa Cave. The species bears an incomplete juvenile skeleton and a partial adult female skull. The primates lived in the Early Pleistocene around 1.98 million years ago, with Australopithecus robustus and Homo ethics described as Erectus. Malapa is understood to be a death trap where creatures may fall by mistake. A. Sediba was once reported as a possible human ancestor and debated as the founder of Homo. The Australopithecus Sediba remains were dates using a combination of paleomagnetism and uranium-lead dating.

Like other australopithecines, Australopithecus Sediba has a brain capacity of 420–440 cc and has a more prominent brow crest and bone structure. Distinctive features from those of other australopithecines include a slight chin. However, such qualities may be a result of adolescence and would fade with adulthood. The dentition is relatively tiny for an australopithecine, while the MH1 measures around 130 cm tall, equating to a body length of 150–156 cm in adulthood.

Reports on the A. Sediba fossil indicate that the primate might have only eaten forest plants like grass species and sedges, as well as fruits, leaves, and bark. This report differs from other early hominins, who ate various savanna plants in abundance but is relevant to regular savanna chimps. Due to the prevalence of an omnivorous diet, the Australopithecus sediba may have lived in a smaller territory than savanna chimpanzees brain size might be 153–201 cc, comparable to common assumptions for other Australopithecus. The brain arrangement appears to have been primarily australopithecine-like, except for the orbitofrontal cortex, which seems quite humanlike. A. Sediba’s upper body shape was apelike, with significantly longer arms, a high brachial index (forearm to humerus ratio) of 84, and broad joint surfaces, similar to other Australopithecus and primitive Homo.

In the absence of significant selective pressures to acquire a more humanlike arm architecture, it is debatable whether australopithecines’ apelike upper limb structure indicates arboreal behavior or is just a basal characteristic inherited from the great ape’s last common ancestor.

The abdominal inlet for a female A. sediba was approximately 80.8 mm x 112.4 mm (3.18 in x 4.43 in) long x broad (sagittal x transverse). So, the prematurity face size was about 89.2 mm (3.51 in) at tallest, the newborn most likely decided to enter the pelvic inlet transversely oriented, as other early humans did. The female and male sizes did not differ as they were the same while both stood upright like human beings and had two legs and two hands. The Australopithecus sediba species was bipedal, meaning they walked on two legs and had similar senses to their predecessor.

Homo Habilis, Homo Erectus, And Homo Heidelbergensis

Homo habilis (also referred to as early or as Homo rudolfensis or just Early Homo)

Million years ago in East and South Africa during the Early Pleistocene. Many academics recommended that H. habilis be synonymized with Australopithecus africanus, the only early hominin known when first described in 1964. However, as time went on and further research gave more attention to H. habilis. By the 1980s, common understanding indicates that H. habilis was a human progenitor that evolved into Homo erectus, which then evolved into modern humans. The method used for dating was radio dating, but it was not accurate, leading to more investigation on rock formation and the rock layers.

Homo habilis brain size was less than Homo ergaster / Homo erectus at the transition between species, going from around 600–650 cc. The H. habilis brain size was about 900–1,000 cc in H. ergaster and H. Erectus. After reappraising the brain capacity of OH 7 from 647–687 cc to 729–824 cc, 2015 research found that the brain sizes of H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, and H. ergaster usually varied between 500–900 cc. However, this situation does imply a change in brain size from australopithecines, which ranged from 400 to 500 cc (24–31 cu in). Homo habilis ate meat through scavenging instead of hunting, posing as hostile scavengers, and taking carcasses from smaller predators like jackals or cheetahs. The fruit was most likely a significant primary source of dietary, as evidenced by teeth degradation caused by acid exposure.

Homo habilis (like other early Homo) did not eat complex meals regularly. Homo habilis walked in two legs and lived in the land. They also lived in caves, and because they were carnivores, they had invented a tool called Odwan which they used in hunting. They used the five sensory organs like human beings as their primary sensory organs. The chest and shoulders of the primitive are broad like that of a modern man, where the male homo habilis had a broader chest.

African Homo erectus (sometimes referred to as Homo ergaster)

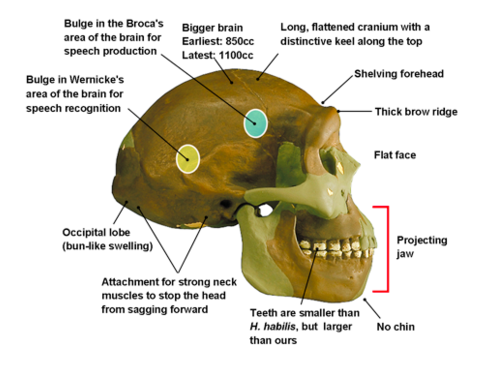

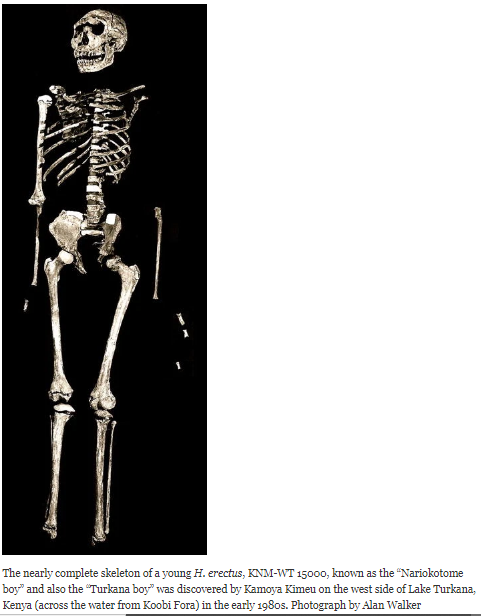

Homo erectus (“upright man”) is an extinct Pleistocene archaic human species that first appeared around 2 million years ago. The remains of this species are among the oldest recognized members of the genus Homo. Homo erectus was the first human progenitor to expand over Eurasia, with a continental range that stretched from the Iberian Peninsula to Java. Homo erectus habitats in Africa are thought to be the progenitors of various human species, including H. heidelbergensis and H. antecessor. The ratio of uranium to radon in a bone or sediment specimen emanates from uranium-series dating. The Homo erectus fossils themselves were dated to be roughly 40,000 years old in another research. The jaw muscle of the primate is estimated to be weaker than that of its predecessors.

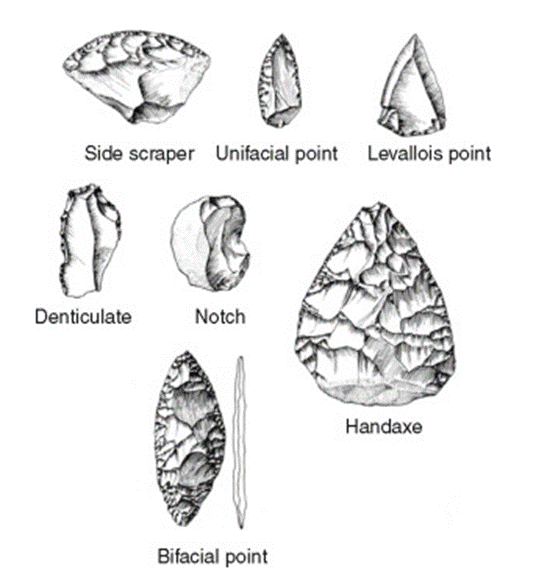

The earliest human species to use hand axes was Homo erectus (Acheulean tools). These tools were intricately carved stone utensils with two sides. The species most likely used the devices for butchering meat and other things. Before that, early human means, such as those used by Homo erectus, were far more basic, consisting of little more than rock flake knapped to a sharp edge. H. Erectus possessed a human-like stride and body dimensions and became the first species to have a flat face, prominent nose, and potentially scant body covered by hair (Schultz et al. 1-45). Although the species’ brain size was much above that of progenitor species, the capacity varied depending on the population. Brain growth appeared to stop early in childhood in earlier people, implying that offspring were mostly self-sufficient from birth, thereby restricting brain skills throughout life.

The homo erectors, compared to modern man was walked upright with two legs. Homo erectus ranged in height from 146 to 185 cm and weight from 40 to 68 kg, owing to geographical changes in temperature, mortality rates, and diet. Unlike other great apes, there does not appear to have been a significant size discrepancy between males and women in H. Erectus. However, there isn’t much fossil evidence for this allegation. Two adults from Koobi Fora had brain sizes of 848 and 804 cc, while another adult had a brain size of 691 ccs, which might imply sexually dimorphic.

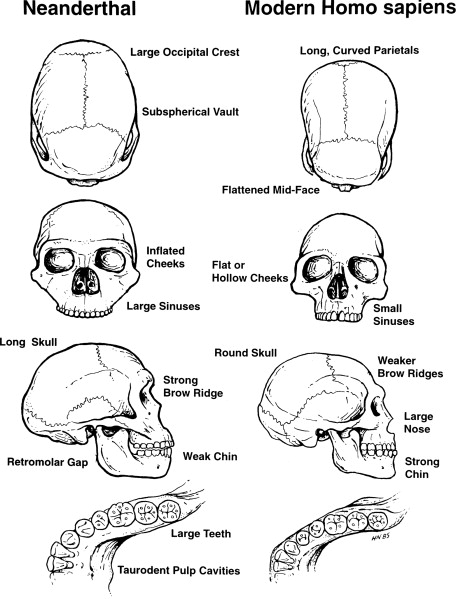

Early Modern Homo Sapiens

The modern Homo sapiens represents a group of species falling under the genus homo and includes all human beings. Scientists using thermoluminescence dating and electron spin resonance dating on teeth collected indicate that the early man lived in Morocco around 300,000 years ago. Other remains have also been found in South-Western Ethiopia, dating approximately 196,000 years. In contrast, the remains collected within the Florisbad site in South Africa indicate that the species lived about 259,000 years ago. The Homo sapiens has a protruding face which a rounded braincase different from the one found on the Neanderthals.

Brain development on this species has been reported, especially within the prefrontal cortex, whose rapid change is due to metabolome evolution echoed by the sudden cutback of muscle strength. The jaws of the early man are smaller compared to those of its earlier species. The last molar teeth and the jaw bone bear the retromolar space while the jaws remain lightly built with a projecting bony chin, strengthening the jaw. The jaw that has been found shorter than the earlier primates bears relatively more minor teeth arranged through a parabolic shape. The front incisor and canine teeth of the species are noticeably smaller.

The body of the modern sapiens comprises of long limbs and slender trunks. The adaptation suits the early man in life at the tropical regions where a more significant proportion of skin surface allowed cooling of the body. Regarding the limbs and the pelvis, the species’ limbs were less robust and thinner than those of earlier species.

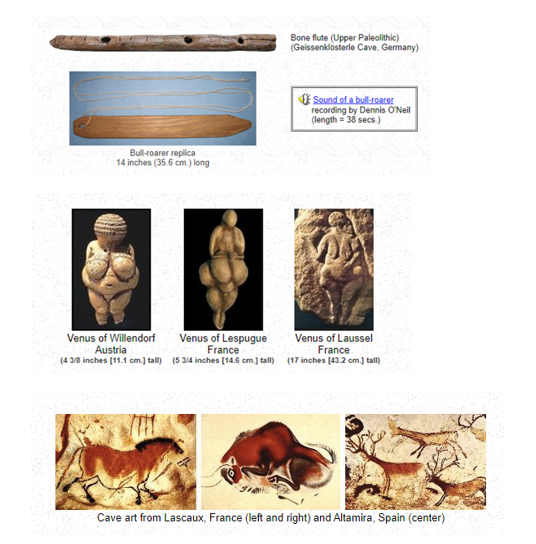

The Cro-Magnons have a larger brain capacity of around 100 cubic inches. Some of the standard tools include paleolithic stone tools like the blade flake. The finishing of the upper paleolithic flake tool was done by applying pressure flaking at the edges of the chips, making them sharper. The chips were fitted in spears or used as knives for cutting meat. The upper paleolithic period saw a shift towards adopting new tools principles, with compound tools being prominent at this time. These tools could be repaired and came in different raw materials, customized through burning, scraping, and hammering. The species gradually replaced wood with bone and antler in making tools, including the harpoon points and sewing needles.

The art of this group includes portable carvings of nude pregnant women known as Venus figurines which symbolized women’s fertility. The Cro-Magnons were known for painting on cave walls where they expressed their feelings, beliefs, and thoughts. The species is understood to make colored paintings of cattle, deer, bison, and other larger animals in caves. Musical tools collected include bone flukes, bullroarers, drums, and whistles, among other devices. The decorative ornaments commonly discovered amongst the Cro-Magnons include pendants and bracelets made of wood and bone remains.

As populations increased, the competition for food also increased, forcing the Cro-Magnons to devise new hunting methods. The species began hunting in groups and started targeting be an even larger game. The species further diversified from hunting large animals like horses to supplementing their diet with fish, small animals, and vegetable foods. Cro-Magnons lived in caves and changed their location in search of food or due to climatic changes. The discovery of children and adult footprints in caves closer to different rock paintings has meant a possibility of initiation ceremonies amongst this group. Homo sapience lived in caves and decollated their caves with drawings and artwork. They also used fire and to burn and soften their food. They walked in two legs like the modern man, and the sensory system is precisely the same as that of a Morden man.

Neanderthals (Homo Neanderthalensis)

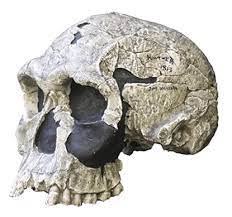

The Neanderthals or commonly referred homo neanderthalensis belong to the genus homo and share a close relationship with modern human beings. Neanderthal refers to the Neander Valley’s current spelling in Germany, where the discovery of the fossil was within the Feldhofer Cave. These archaic humans occupied Eurasia until around 40,000 years ago. A close MtDNA analysis reveals that 600,000 years ago, the Homo heildelbergensis trekked out of Africa and settled in Europe. Those who settled in Europe became the Neanderthals, while those in Africa evolved to the Homo sapien.

Neanderthals developed better adaptions to cold climates than modern humans due to their settlement around the south of Europe along the line of glaciation. When temperatures became warmer, the species relocated to the North. The cranial capacity of the species is close to that of modern man, while Neanderthals were more robust than modern humans. The species possesses a low-vaulted skull and lower jaw. The Neanderthals had nasal openings, large arched brow ridges, and prominent orbital. A space between the last molar and the ascending edge within the lower jaw was prevalent amongst this species. Though the species had more prominent front teeth, the molars and premolars were the exact sizes of modern humans.

The discovery of the Mousterian tools was at a period and locations where the Neanderthals lived. Mousterian devices made through the Levallois flakareg method are often associated with flakes chipped from available Common Mousterian tools include hand axes, sidescrapers, and triangular points, which were used as knives. Evidence indicates that the Neanderthal used to bury the dead at different locations, particularly at La Chapelle-aux-saints, Laquina, and Roc de Marsal in France. This discovery alludes to that the species practicing ritualistic and symbolic cultural behaviors. The species’ diet was made of plant produce, terrestrial, riverine, and marine food resources.

The Neanderthals lived like today’s hunters and gatherers and lived in groups of 10-30 people, including adults and children. Different researchers have developed another hypothesis to explain the disappearance of Neanderthals 40,000 years ago. Some scientists argue that modern humans murdered the species as they have begun to disperse across Europe. Other researchers indicate that the species might have disappeared due to chronic diseases transmitted to modern humans. There is also a hypothesis that the Neanderthals and high plant cover were destroyed by the volcanic eruption in Europe or the cold weather. However, these assertions have been discredited by different scholars. They walked using two legs like ordinary human beings. They lived in caves and also had clothes to cover them from the cold winter. Their sensory organs were the same as that of a modern man. The “anterior dental loading” idea proposed that Neanderthals had a protrusion of the jaw.

Work Cited

Schultz, Shook Beth Alison et al. “Primate Evolution.” Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, American Anthropological Association, Arlington, VA, 2019, pp. 1–45.