Introduction

It is a renowned statistic that cigarette smoking is much more common among the patients with psychiatric diseases for a number of reasons which may include (but are not limited to) psychological implications and neurobiological mechanisms. The addiction to nicotine is often associated with co-occurring psychological ailments and is known to increase the risk of being exposed to mortality, different types of injuries, and devastating influence of the combination of smoking and depression on the smokers’ lives (Aubin, Rollema, Svensson, & Winterer, 2012).

The psychosocial connections between the two are recurrently confirmed by the neurobiological implications of depression. It is also interesting that smoking has a certain influence on the cholinergic system. As a consequence, smoking individuals suffering from depression may improve their concentration and perception of the world. Therefore, despite a commonly adverse connotation of smoking, a number of pleasurable sensations are associated with this bad habit (Clancy, Zwar, & Richmond, 2013).

The patient population has to be evaluated in line with the existing evidence regarding the fact that psychosocial interventions are relatively ineffective in terms of smoking cessation and accompanying depression. The problem consists in the fact that this particular population (depressed individuals who are going through the process of smoking cessation) is currently undertreated, and the existing treatments are inflexible and generalized (Hitsman et al., 2013). The researcher is willing to observe the relationship between the research variables and draw relevant conclusions regarding depression outcomes in both patients who went through smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking.

Aim and Objectives of the Study

The aim of the study is to scrutinize the issues inherent in the process of smoking cessation and align them with the occurrence of depression in an extensive sample of individuals who are not divided into groups on the basis of their gender, racial, or any other differences. The key objective of the study was to validate the thesis statement of the study: smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking have no influence on depression outcomes and will be corroborated by means of the PHQ-9 scale at the day of quitting cigarette smoking and followed up during the period of smoking cessation. In order to validate the thesis statement successfully, it is necessary to conduct an extensive literature review, pick an appropriate research methodology, and conduct the experiment (survey).

Literature Review

In their research, Gierisch, Bastian, Calhoun, McDuffie, and Williams (2012) conducted a review regarding the process of smoking cessation among the patients who suffered from serious depressive disorders. They found that the effectiveness of the existing strategies of increasing abstinence rates majorly depended on the transpiring depressive symptoms. The data also related to the smokers who had depression in the past in addition to those who suffered from depression at the time of conducting that research project (Gierisch et al., 2012).

Despite these linkages, the results of the study allowed the researchers to suggest that there is a chance to encourage patients suffering from depression to engage in smoking cessation activities so as to manage their mood resourcefully. The results of this research were also supported by the findings presented in the article written by Mathew, Hogarth, Leventhal, Cook, and Hitsman (2016). They identified that the existence of a connection between smoking and depression negatively impacts the cessation rates among those who suffer from moderate and severe depressions.

Therefore, the researchers suggested that it is necessary to focus on the psychological state of the patients because the latter may subsidize to the advent of disproportionate motivators of smoking and block the cessation process (Mathew et al., 2016). One of the things that were found to contribute to decreased levels of self-control was cognitive impairment. The researchers supposed that it would be reasonable to conceptualize the psychological mechanisms of smoking cessation and find a way to maintain their depression-quitting behavioral patterns. Therefore, the authors of the article advocated for the creation of a framework that would take into consideration the internal state of the individuals so as to mitigate the outcomes of depression.

Leventhal, Piper, Japuntich, Baker, and Cook, (2014) discussed the outcomes of depression during the lifetime and smoking cessation. They believed that the process of smoking cessation seriously impacted the outlooks of depressed patients and these two activities could interfere with each other on a psychosocial level. Leventhal et al. (2014) conducted research intended to assess the contributions of disinterest and depressed mood to the development of depression and its subsequent outcomes.

The results of the study showed that depressed mood and smoking cessation activity were interconnected in 95% of the cases. Regardless, the outcomes of depression could not be predicted solely on this data (Leventhal et al., 2014). The researchers concluded that we should pay more attention to anhedonia instead of trying to associate smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking with the outcomes of depression.

In their research, Ragg, Gordon, Ahmed, and Allan (2013) also investigated the issues of connecting depression to the process of smoking cessation. They wanted to validate the thesis statement that claimed that people suffering from depression were more susceptible to being exposed to the aggravated symptoms of depression. The results of the study suggested that there were no particular changes in patients’ mental health during or after the process of smoking cessation (Ragg et al., 2013).

The researchers did not find any sign of intensified symptoms of depression and concluded that the outcomes of depression did not differ between the two types (smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking) of patients. Therefore, the findings of this particular research support the findings that were presented by other researchers in the area because smoking did not bear a mediating connotation in the relationship between smoking cessation and the outcomes of depression. Another research on the topic was conducted by Scherphof et al. (2012) who sufficiently addressed the issue of the interconnection between smoking and the symptoms of depression.

The findings of the study showed that even though a relatively high number of individuals smoked with the intention of weakening their depression symptoms, the effect was insignificant. The process of smoking cessation did not trigger any variance in research results as well because no connections were found between depression-quitting smoking and the outcomes of depression.

Methodology

Sampling Method

Within the framework of the current research, the investigator uses typical case sampling. This sampling method is used because the researcher is interested in analyzing the normality of smoking cessation and occurrence of depression in the chosen sample because these two aspects are usually referred to as interrelated. The sample included a total of 50 men and women (aged from 18 to 65) that went through the process of smoking cessation and were asked to fill in PHQ-9 depression tests before and after smoking cessation. In the case of the current research, the word “typical” does not mean that it relates to probability sampling.

Instead, the researcher is interested in applying typical case sampling because it will allow the researcher to compare the results achieved within this sample with other similar samples. The researcher does not generalize the sample because the objective of this study is to compare the sample of people who went through smoking cessation to a sample of people who did not.

Data Collection

The data was collected by means of the PHQ-9 depression tests. First, the researcher took the sample and asked the participants to fill in their surveys before they went through the process of smoking cessation. This was necessary to identify if there are any variations between the samples (including those individuals who were not affected by depression) and outline the differences that may support the thesis statement. The participants of the experiment were invited to a facility and filled in their surveys simultaneously so as to make the research process more time- and resource-effective. Each of the participants had their own desk and were asked to work on their surveys individually and not talk to each other prior to or during the process of filling in the PHQ-9.

Study Variables

The researcher identified a number of variables and successfully operationalized them. Independent variables included participant gender, participant age, and smoking cessation. Dependent variables included the occurrence of depression, indicators of depression, the prevalence of depression among the participants who went through smoking cessation, and outcomes of depression. Male and female participants aged from 18 to 65 were exposed to the process of smoking cessation intended to help them manage their (subsequent) depression. The researcher expected to measure the occurrence of depression among those participants, categorize the key indicators of depression in the chosen sample, and evaluate the efficiency of smoking cessation in terms of mitigating the outcomes of depression.

Discussion

This research helped the investigator to evaluate the dependencies between smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking and assess the outcomes of depression by means of processing the data obtained from the PHQ-9 questionnaires.

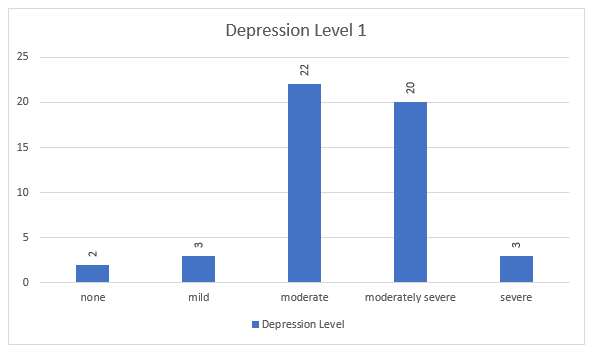

The evidence that was found by the researcher suggests that there is no practical variation between the outcomes of depression in both cases. Nonetheless, the results of the survey helped the researcher to conclude that depression-quitting smoking has a slightly more authoritative influence on the individual’s ability to manage their mood if compared to the conventional smoking cessation process. Another important finding of the study consists in the fact that either past or current depression significantly impacts the smokers and increases cessation rates. The analysis of the outcomes showed that the level of depression was perceptibly identical for the majority of the sample (see Figure 1).

This may mean that the prevalence of depression cannot be mitigated by smoking cessation or depression-quitting smoking. Instead, the measurements may indicate that smoking cessation may be influenced by depression but not vice versa. The researcher can reach a verdict regarding the long-term abstinence and conclude that depression adversely impacts the ability of depressed people to resist smoking habit.

Moreover, according to the results of the survey, the researcher can validate the thesis statement and confirm that there is no visual difference between the two major partitions of the sample. It is also safe to say that no extreme data fluctuations were identified within the framework of the research as the findings of the study supported the thesis statement and stayed within the predefined limits. The researcher was interested in defining the influence of psychosocial interventions, and PHQ-9 survey allowed them to certify that mood management may become one of the future implications of this study.

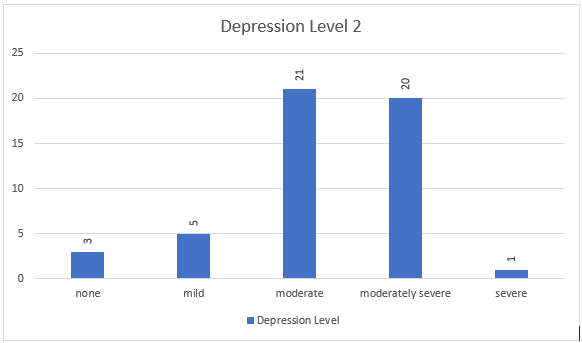

The results of the experiment can also be explained by the comparison of the results of the designated sample to the occurrence of depression in depression-quitting smokers (see Figure 2). It can be noticed that the differences are minimal and cannot be considered causal within the framework of this research.

After the review of the results, the researcher can also conclude that psychosocial mood management should become one of the future research directions in the area. The effects of depression during the process of smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking were defined as equal.

Study Strengths, Limitations, and Ethical Considerations

One of the strengths of the study consists in the fact that it defines the relationship between depression and smoking cessation/ depression-quitting smoking. Regardless of the small size of the sample, the research was able to verify and validate the thesis statement and answer the research questions. The objective of the study was also achieved. It is critical to take into consideration, though, that the validity of the obtained data was supported by the sources that were studied during the literature review stage.

Another strength of the research consists in its straightforwardness as the results of the study support the belief that depression is a rather relative concept and the impact of either smoking habit or smoking cessation did not impact the reliability of the data (Leventhal & Zvolensky, 2015).

Regardless, several limitations of the study are also in place. The key limitation of the study consists in the fact that the reliability of the data can be seriously undermined by the partiality of the sample. This particular issue cannot be mitigated within the existing research. Another limitation of the study lies in the fact that the size of the sample was relatively small so the typical case sampling can be characterized as somewhat inefficient (Richards, Cohen, Morrell, Watson, & Low, 2013).

The researcher conducted the experiment in compliance with all the ethical considerations. The participants of the study were explained all the details of the study, and then the researcher obtained the informed consent of the participating individuals. The researcher presented information regarding the purpose of the research, procedures inherent in the research process, and approximate length of the experiment. After the research was over, the investigator discussed the results with the participants and asked for the feedback. Most importantly, the researcher made their best effort to protect the participants from physical and mental harm.

The investigator did not mislead the participants or created any ambiguity by not disclosing the results of the study to the participants. All the data obtained from the interviewees was confidential, and no names were used in the reports. The researcher also informed the participants of the study that they are able to withdraw from the experiment at any given period of time without any consequences.

Conclusion

The problem with the relation between smoking and depression consists in the fact that the majority of health care professionals consider the situation relatively hopeless (mainly because the common expectations revolve around the idea that if the individuals are depressed, they will not be willing or able to quit. The results of this particular study showed that smoking cessation did not trigger or aggravate any of the underlying symptoms of depression.

This particular finding can be named one of the biggest contributions to the body of research on this topic as it adds value to the existing evidence regarding the connection between smoking cessation and the level of depression. Therefore, the researcher suggests that it is important to continue research on the topic as quitting smoking does not impact the patients suffering from depression in a way that can be viewed as insignificant on a bigger scale. The literature review that was conducted within the framework of this research showed that even past history of depression does not have an impact on the smoking cessation process.

The majority of severe depression symptoms did not transpire throughout the depression-quitting smoking either. Therefore, the researcher is able to conclude that the findings of the study do not bear a negative connotation for either the smokers suffering from depression who want to quit or depression-quitting smokers. Taking into account all the information presented above, the researcher is also capable of concluding that the individuals who go through the process of smoking cessation are exposed to a higher risk of being affected by the negative aspects of depression (but it is reasonable to mention that the data concerning this particular issue is vague and necessitates further research on the subject).

The symptoms of depression were not found to intensify or grow drastically in the research sample, but the researcher believes that it is important to investigate the issue of probability of depressive episodes in the individuals who just quitted smoking. The impact of the mood of the participants of the study can also be identified as an important factor that has to be studied further because the severity of depressive symptoms may bring duality into research and make the validity of the obtained data rather questionable. This may be done in order to foresee the issues that may transpire during the smoking cessation-induced depressions and increase the smokers’ vulnerability to the symptoms of depression.

Overall, the researcher was able to validate the thesis statement and answer the research question in a comprehensible manner. All the variables that contribute to the impact of depression on smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking were also studied and evaluated. The data that was obtained during the experiment showed that there were no peculiar differences between the process of smoking cessation and depression-quitting smoking habit. On the basis of this data, we may conclude that the impact of these two factors on depression outcomes is merely identical but can be influenced by certain external factors such as resilience, the stability of mental health, and willingness to quit smoking.

References

Aubin, H., Rollema, H., Svensson, T. H., & Winterer, G. (2012). Smoking, quitting, and psychiatric disease: A review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(1), 271-284. Web.

Clancy, N., Zwar, N., & Richmond, R. (2013). Depression, smoking and smoking cessation: A qualitative study. Family Practice, 30(5), 587-592. Web.

Gierisch, J. M., Bastian, L. A., Calhoun, P. S., McDuffie, J. R., & Williams, J. W. (2012). Smoking cessation interventions for patients with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(3), 351-360. Web.

Hitsman, B., Papandonatos, G. D., Mcchargue, D. E., Demott, A., Herrera, M. J., Spring, B.,… Niaura, R. (2013). Past major depression and smoking cessation outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction, 108(2), 294- 306. Web.

Leventhal, A. M., Piper, M. E., Japuntich, S. J., Baker, T. B., & Cook, J. W. (2014). Anhedonia, depressed mood, and smoking cessation outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(1), 122-129. Web.

Leventhal, A. M., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2015). Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: A transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion– smoking comorbidity. Psychological Bulletin, 141(1), 176-212. Web.

Mathew, A. R., Hogarth, L., Leventhal, A. M., Cook, J. W., & Hitsman, B. (2016). Cigarette smoking and depression comorbidity: Systematic review and proposed theoretical model. Addiction, 112(3), 401-412. Web.

Ragg, M., Gordon, R., Ahmed, T., & Allan, J. (2013). The impact of smoking cessation on schizophrenia and major depression. Australasian Psychiatry, 21(3), 238-245. Web.

Richards, C. S., Cohen, L. M., Morrell, H. E., Watson, N. L., & Low, B. E. (2013). Treating depressed and anxious smokers in smoking cessation programs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(2), 263-273. Web.

Scherphof, C. S., Eijnden, R., Harakeh, Z., Raaijmakers, Q. A., Kleinjan, M., Engels, R. C., & Vollebergh, W. A. (2012). Effects of nicotine dependence and depressive symptoms on smoking cessation: A longitudinal study among adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15(7), 1222-1229. Web.