Introduction

For my assignment, I have chosen the Mass Transit Railway (MTR), a Hong Kong-based company. Out of the various ongoing projects, I plan to do the Project Management Report on the West Island Line (WIL) project. The length of the route will be about 3 km, and the capacity and frequency of the train shall be 85,000 passengers per hour per direction.

Principles of Project Management

Background and Principles of Project Management

Gray & Larson (2008) define a project as a unique entity that aims at a previously defined goal, consisting of complex, interrelated tasks, and is limited by time, costs and its scope. Both the contractor and the client aim for the goal in pursuance of strategic targets. The goal of the MTR West Island line is to provide a fast, efficient and reliable commuter service to residents of the Western District of Hong Kong Island (MTR, 2013).

Gray & Larson (2008, 26) state that each project is unique, as it has never been done before and is unlikely to be repeated. Project objectives are determined by the parameters of time, cost, and quality (also referred to as performance). The time scheduled for the completion of the WIL project is just under five years, from July 2009, which marks the beginning of construction, until the end of 2014, when the project is to be completed in its entirety (MTR, 2013). They are also limited by costs, as resources are limited, which restricts each project to a limited budget. The cost of the entire WIL Project is estimated to be HK$ 15.4 billion, and by the date of its completion, it is estimated that it will have employed 6,600 people (MTR, 2013).

Time, cost and quality/performance have to be balanced for the most favourable outcome. Thus, time, cost, and quality/performance are a triangle of objectives, referred to as “the magic triangle of project management”. If one is affected, the two other objectives will also be affected. However, the quality/performance objective is often considered paramount (Lock 1996, 9). The government intends the West Island Line to provide a dependable railway service to Hong Kong Island. It will serve a population of 200,000 people in the Western District, by offering them access to Sai Ying Pun Station within 8 minutes, and seamless access to Tsim Sha Tsui station in Kowloon (on the Hong Kong-mainland) within 14 minutes. Furthermore, the majority of the residents of the Western District will walk to access the WIL.

Viability of Projects

The West Island Line is a viable project, and this assertion is supported by the results of several studies, based on successful projects in Hong Kong, which used the tunnel excavation methods that are currently being used in the construction of the West Island Line. An example of such a viable project is the Island West Transfer Station, which is an underground waste transfer facility on Hong Kong Island. At the time of its completion, it was the largest ever excavated rock cavern in Hong Kong, with a length of 60 metres, a width of 27 metres and a height of 12 metres (CEDD 2009, 9). The construction of such a large cavern on Hong Kong Island, near the site of the West Island Line, proved that it would be viable to excavate railway tunnels on Hong Kong Island.

Project Viability is assessed through the process of Project Viability Screening, which is a merit-based analysis, which ranks projects using a set of project viability criteria (Orr & Tchou, 2009, 19). It consists of seven steps, as stated below:

- Establish an Integrated Team

- Develop Project Viability Criteria

- Deal-Breaker Screening

- Project Viability Screening

- Prepare Project Short-List

- Prepare Feasibility/Business Case

- Obtain Board Approval (Orr & Tchou, 2009, 20).

The West Island Line (WIL) was viable at its inception in 2009. This is attested to by the endorsement by the Hong Kong Executive Council of the funding schedule for the WIL Project (HK$15.4 billion over five years) in May 2009, and the subsequent funding approval given by the Legislative Council in July of the same year (MTR, 2009). Therefore, the relevant authorities were confident that the project could be built within its scheduled cost right from the start. In terms of meeting the project’s performance/quality specifications, it was anticipated that the West Island Line would be capable of transporting 85,000 passengers per hour per direction. As the West Island, Line would be an extension of the MTR Island Line, and as Mass Transit Railway (MTR) would operate it, the performance/quality aspects of the project were also considered viable from the start (MTR, 2013).

Systems and Procedures

Initially, the Project Agreement was signed between MTR and the government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) in 2009 (MTR, 2013). The determination of project milestones followed this. The appendix outlines the process of selecting key events, titles, definitions, deadlines, and decision points that framed the project. These milestones are set out in Appendix 1. In collaboration with the associate project manager and the control account manager, the project manager, identified the intermediate (short-term) milestones, which are shown in Appendix 3. From this point, the control account manager developed a detailed schedule for each control account. The Project Manager gives details work and milestones related to specific work packages and allocates them to sub-contractors. They were then integrated into the project milestones. The project manager then approved the project detail schedule, and the project schedule baseline was drawn up and integrated into the activity schedule in the schedule baseline to form the project Time-Phased Cost Profile, in conformance with AGCA (2003, 11).

Key Elements

The construction of the tunnel from Sheung Wan Station via Sai Ying Pun Station and Kennedy Town was managed in two phases. A consortium of firms, Dragages, Maeda and BSG, did the tunnel between Sheung Wan and Sai Ying Pun Stations. The section of tunnel between Sai Ying Pun and Kennedy Town Stations, including the construction of Hong Kong University Station, is a joint venture between Gammon Construction Ltd, Nishimatsu and WIL. Gammon Construction Ltd. is constructing Kennedy Town Station. These sub-projects are ongoing and nearing completion (MTR, 2013). The termination of these parts of the project should follow a laid down procedure. Once the project manager considers the work completed, but before workers leave the project, he should prepare a list of items requiring correction or completion. Subcontractors should promptly satisfy such requirements and arrange for any contractually required tests (AGCA, 2003, 55). Thus, each of the subcontractors and or joint ventures working on different sections of the tunnel should be prepared to conduct these tests and to do any other work, which the project manager considers necessary before the project, can be said to be complete (Schwalbe, 2013).

Once each subcontractor has substantially completed the work or designated portion thereof as listed, the project manager should verify that each subcontractor’s work is substantially complete and then request a prompt substantial completion inspection by the project client (in this case, MTR) as contractually required. The project manager should be present during the inspection process, along with the project representative(s) of the subcontractor(s) whose work is being inspected (AGCA, 2003, 55).

Once the completion inspection has been done, the project manager should carry out a Post-project appraisal. Post-project appraisals (PPAs) are evaluations of the effectiveness of projects based on systematic data collection. Specifically, PPA represents an opportunity to determine if the project was completed well, and how to improve future restoration design (Skinner 1999, adapted from Sadler 1988). The PPA allows the project manager to assess whether the sections of the project performed by different sub-contractors work together as an efficient, harmonious whole.

Project Organization

Organizational structure

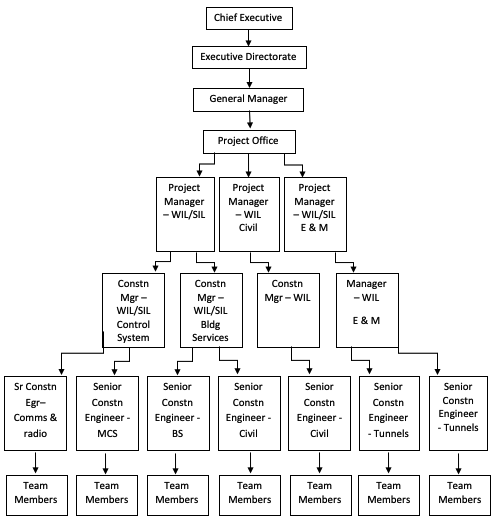

The organization chart of the MTR-WIL is appropriate for WIL as it is specifically designed for the WIL project. MTR is the parent organization, and WIL has been established to build the Western Island Line. Some of the project participants are permanent employees of MTR, while others are experts who have been hired for the WIL project. The organization chart is shown in Appendix 2 (Kay, 1993).

The CEO of MTR is the head of the Executive directorate. Other members of the Executive directorate are the heads of different divisions of the project. Senior managers in supervising the project and apprising the board (of MTR) of the progress and performance assist the heads of such departments. Following is the management team at WIL:

- Mr Rod Hockin: General Manager – WIL/SIL, who has overall responsibility for the completion of WIL. Reports to the Executive Office.

- Mr Brenden Reilly: Project Manager – WIL Civil, in charge of civil engineering aspects of the WIL project. Reports to General Manager.

- Mr Dono Tong: Project Manager – WIL/SIL E&M. He coordinates the project objectives (time, cost and performance/quality). Reports to General Manager

- Mr Stephen Hamill: Construction Manager – WIL. Supervises construction and reports to Project Manager.

- Mr David Salisbury: Construction Manager – WIL. Supervises construction and reports to Project Manager.

- Mr Herbert Leung: Construction Manager – WIL/SIL Control System. Supervises installation of the control system and reports to the Project Manager.

- Mr K. M. Lock: Construction Manager – WIL/SIL Building Services. Supervises construction and reports to Project Manager.

- Mr P. W. Lau: Design Manager – WIL. Is responsible for designing and implementing the final appearance of the WIL. Reports to Project Manager.

Following is the list of engineers from various departments within WIL:

- Mr Tom Barret: Senior Construction Manager – Tunnels

- Mr Ashley Calvert: Senior Construction Manager – Tunnels

The two Senior Construction Managers/Engineers above are responsible for the supervision of all tunnelling aspects of the project. As the project has been divided into sections under different subcontractors, who use different methods of tunnelling, each construction manager will have separate responsibilities. They report to the Construction Managers.

- Mr Patrick Cheng: Senior Construction Manager – Civil

- Mr Walter Lam: Senior Construction Manager – Civil

The two Senior Construction Managers/Engineers for Civil Engineering will oversee all civil engineering work on the project. Similar to their superiors, they supervise different subcontractors who are performing different sections of the project. They report to the Construction Managers.

- Mr James Ho: Senior Construction Manager – Comms & Radio

He implements and supervises the work of installing and testing the communication and radio systems for the WIL. He reports to the Construction Manager – WIL/SIL Control System.

- Mr Kenneth Lo: Senior Construction Manager – BS

He and his team are tasked with the construction (building services) that takes place after the tunnelling has been completed. He reports to the Construction Manager – WIL/SIL Building Services.

- Mr Rodney Ng: Senior Construction Manager – MCS

He and his team are responsible for the installation and operation of the WIL Main Control System (MCS). He reports to the Construction Manager – WIL/SIL Control System.

Project Implementation Control

The project manager at WIL controls and coordinates the project through the managerial actions of planning, organizing, and leading, among others. Project managers’ actions are constantly aimed at change, while other managers’ jobs involve maintaining a stable working environment (Brown 1998, 13.)

Thus the WIL project manager has to be a team manager, by interacting with project members, from the General Manager, Construction Managers and Engineers to the builders, drillers and technicians at the site. As the WIL project involves international expertise, the project manager has to build team ethos in a multicultural and multilingual group of project staff. Earning the respect of the team is crucial for the project manager; therefore, he/she must be a person of utmost honesty, integrity and vision. (Lockyer & Gordon 1996, 17). The project manager shall control the project constraints to ensure that everything goes as planned. The constraints are time constraint, quality constraint, cost constraint, and scope constraint. The manager will do this by checking project specifications, schedule, and budget allocations. The project manager will use the tools outlined below for that purpose (Chase & Aquilano, 2006).

Control Point Identification Chart

The chart below will be useful for tracking areas that may go wrong and anticipating ways in which the project manager will solve the problems to avoid nasty surprises. Table 1 shows some of the problems that may occur during the WIL project, how to identify the problem, and the possible solutions.

Table 1: Control Point Identification Chart.

Milestone Charts

This powerful implementation tool summarizes the status of a project by highlighting key events. Milestone charts state what events in the project’s life have been completed. Also, the chart states the duration it took to complete the events, and, whether this is the duration, the project manager had scheduled for the event (Chase & Aquilano, 2006). Hence, the manager continually records the variance between the actual and scheduled times. Also, it outlines the remaining events and the project manager’s anticipated completion time. Table 2 below shows the Milestone chart for the WIL Project. The project is at its fourth year and as the table indicates, the actual completion times for the remaining “milestones” have not yet been determined.

Table 2: Milestone Chart.

Project and Budget Control Chart

Project and budget control charts record cost, schedule performances to ascertain actual and planned performances of the project. Normally these are based on the nature of the work breakdown structure (Chase & Aquilano, 2006). It makes use of the work packages. In this project, this may not be as applicable but may be useful. The project manager will obtain cumulative amounts for the actual and scheduled performances and drawbar graphs for comparison, as shown in Table 3 below. The above analysis may act as an early indicator as to whether the project manager will meet the parameters of the project (Reiss, 2007). Hence, it may be used as an effective tool to source for additional time or resources from management. If it is a strict-schedule project, this parameter may offer a way for the manager to organize for overtime and to crash the network diagram for a scheduled finish (Chase & Aquilano, 2006).

Table 3: Project and Budget Control Chart.

Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

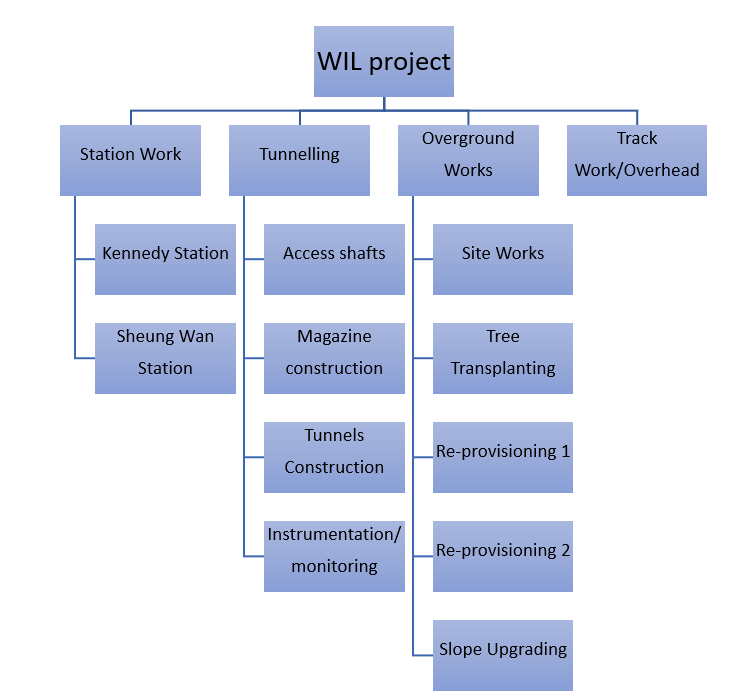

Work Breakdown Structure

The project manager will subdivide the project scope into manageable segments, assign them to the respective individuals, and document that information. The project manager shall specify the specific requirements of each subunit. This includes approximate budgetary allocation, performance standards, and durations. The project manager will aggregate this information into a clear format for ease of reference. Figure 1 below is a representation of WIL’s Work Breakdown Structure.

Project Leadership Requirements

According to Lockyer & Gordon (1996, 17), requisite skills of a project manager include technological understanding, being well versed in project economics, skill in man management, competence in systems design, maintenance, planning and control, financial competence, procurement competence, and good interpersonal communication skills. Their character traits ought to include drive, enthusiasm, dedication and humour, and a willingness to support their staff when things go wrong (Lockyer & Gordon, 1996, 17).

At WIL, Project leaders are selected based on their leadership qualities. For instance, the project manager organized a press conference to spread the awareness of noise pollution and how MTR will reduce this kind of pollution (MTR 2012, 1). He also arranged with renowned people from society for a similar purpose. This shows his communication skills. Whenever the workers have any technical problem, they always take advice from the project manager. This shows his expertise in technical matters as well. The project manager is an efficient leader as well, and he can keep unity among the workers. This develops a feeling of teamwork, and the work is accomplished with ease.

To keep the work going on smoothly, it is very crucial to maintain an organized workforce. The project manager is an expert in leadership qualities. He knows how to handle such a huge workforce. At weekends, after the duty hours, he gathers all the workers and arranges tea and snacks for them. He addresses them sympathetically and asks for any problems that they might have. This behaviour of the project manager garners honour and respect for him. The workers come forward and express their problems, and in turn, the project manager tries his level best to find solutions (Johnson, Whittington & Scholes, 2011).

Communications Matrix

Risk Matrix

Human resources and requirements for MTR project

At the start of the MTR West Island Line Project in 2009, it was anticipated that the project would create a total of 6,600 jobs over the five year period of line construction, with peak employment numbers of 3,000 employees maximum (MTR, 2009). However, the vast majority of the jobs created during the construction phase are temporary, with permanent operational staff to be engaged once the West Island Line is complete. The temporary construction employees include 1,500 people who were hired in October 2011 (MTR, 2011, 2). As regards operational staff, MTR has not yet released figures for the number of people to be employed, but it is anticipated that they will do so once they are prepared to hire them.

Project Process and Procedures

Project Plan

The WIL project is scheduled for completion by 2014. A project plan of MTR is tabled at ‘Appendix 1’. A detailed schedule is at ‘Appendix 3’.

The WIL project plan can be described in terms of the six project phases developed by Brown (1998, 10.) namely initiation, specification, designing, building, installation and operation. The gazettal of the WIL project under the Railways Ordinance falls under the initiation stage, in which the terms of reference and objectives of the project are set up, and budgets are approved.

The scheme authorization of the WIL project under the Railways Ordinance, which occurred in 2009, is part of the specification phase.

This is followed by the design phase, where the project stakeholders (architects, construction managers, engineers) explain how the project will meet the commuter needs stated in the specification phase. The next phase is building. WIL entered this phase in July 2009, with the commencement of West Island Line construction. Although the prior phases were carried out over nearly two years, Brown (1998, 12) insists that projects should not rush directly into the building, as poor specification and design may result in delays and budget overlaps. The construction phase included some civil work in neighbourhoods that have been affected by the WIL, such as the re-provisioning of David Trench Rehabilitation Centre, and the re-provisioning of Kennedy Town Swimming Pool (Phase I) which were completed in April and May 2011, respectively. The laying of the railway track began in June 2012, while the mechanical and electrical work started in September 2012. The breakthrough of railway tunnel from Sheung Wan station to Kennedy Town station occurred in November 2012 (MTR, 2012). The track laying, mechanical, and electrical work is ongoing.

The government expects that WIL’s installation phase will be complete by 2014. The final phase is operation and review. It can be said to be a continuation of testing. Once the project is operational, there should be reports at periodic intervals detailing how the project is running and any flaws that need to be corrected.

Project scheduling, estimating and cost control techniques

Project scheduling, estimating and cost controls are the main factors of a project management system. For companies engaged in future construction, the right forecast of the future project cost is very significant (Manfredonia et al., 2010).

The WIL Project Plan, mentioned above, is the basis of the project scheduling and cost control in WIL. Once the prospective subcontractors have been informed of the deadline for completion of their subcontracts, they submit their bids. Those, which fit within the WIL project plan parameters of time cost and quality, are selected and permitted to proceed. This is carried out at the specification phase. However, this is an ongoing process, as a subcontractor may go over budget. This is the responsibility of the particular subcontractor involved, who will cover all extra costs (MTR, 2013).

Scheduling often begins tentatively, with more detailed schedules being developed as the process proceeds. This requires consistent communication between the project manager and project stakeholders, as they will need to be informed of scheduling changes or delays in implementation. It is due to the tentative nature of scheduling that cost control is also a dynamic process. The initial schedule and cost estimates need to be revised in the light of new information acquired during the project lifespan. This means that scheduling and cost control will fluctuate during the project, as the project manager adjusts to changing circumstances.

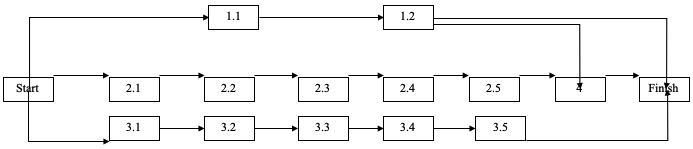

Network Diagrams

There are two types of network diagrams. These are very useful tools in project control. There are two types of network diagrams: Project Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) and Critical Path Analysis (CPM). They are complex decision-making tools that enable project managers to organize work and plan workflows. They provide necessary information that is vital in scheduling and budgeting. This information includes the earliest start times of a project, the latest completion times, time floats, and the critical path. The critical path is the longest route in a network diagram that indicates the time the project will take. It is hard to construct a network diagram for a project with complex times and huge budgets, but the availability of software for that purpose makes it easy. In this project, the techniques may be useful to the project manager in evaluating the progress of the project.

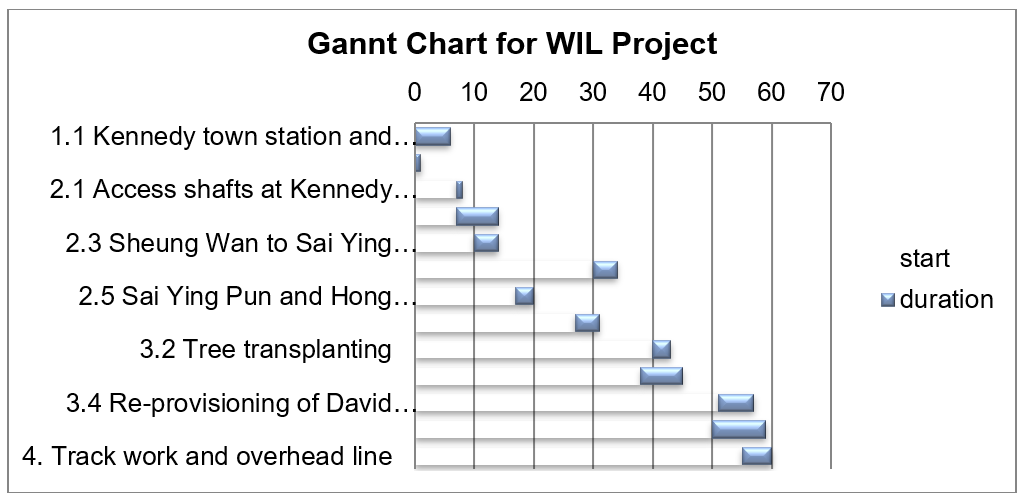

Use of a Gantt chart

This project’s project manager may find it quite useful to engage the use of a Gantt chart in managing complexity in cost and time. A Gantt chart is an intricate tool used for the management of interrelated tasks with different durations. When using a Gantt chart, the project manager assumes that the tasks are linear, and their durations can be determined beforehand with a high degree of precision (Reiss, 2007). However, management should have duration estimates with the relevant possible contingencies.

A Gantt chart has several benefits to the project manager. First, diagrammatically represents the whole project. This makes it easy for the project manager to identify the activities to complete first and clearly, shows the relationships between tasks. Second, it shows the duration of a project. However, in as much as it may show the tasks clearly, it does not indicate dependencies among tasks and the project manager may not know from the Gantt chart how the delay of one task may affect another. For this purpose, the project manager will have to use the network diagrams (Chase & Aquilano, 2006). Figure 2 below shows the Gantt Chart for the WIL project. It indicates the start times and durations for each activity. However, it does indicate the costs. The durations are indicated in months.

Table 4: Activity Durations for Gannt Chart.

Methods used to measure project performance

Measuring performance is used to determine the success or failure of a project. The project is successful if it has been completed according to specifications and on time. However, for a long-term project such as WIL, these criteria cannot be used to assess the entire project while it is still ongoing. However, they can be used to measure the performance of project tasks, which are an indicator of the eventual outcome of the project.

As the project parameters are time, cost and performance, the first measurement parameter for WIL is whether the subcontracts have been completed on time and within budget. In terms of performance, some aspects of the project can only be assessed when it is complete. Nevertheless, if quality control is done for each segment of the project as and when it is completed, the likelihood of the completed project meeting and exceeding performance requirements will be increased (MTR, 2013).

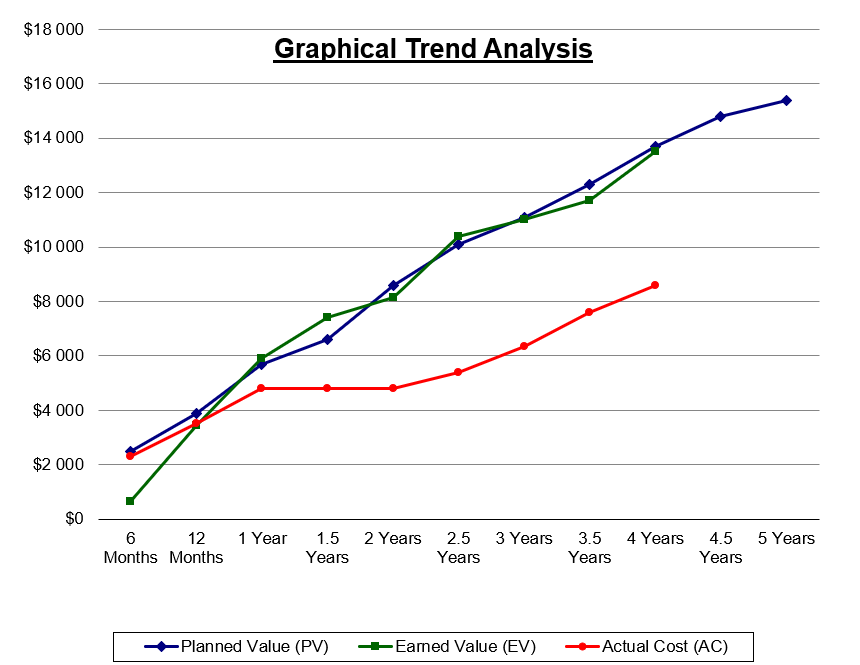

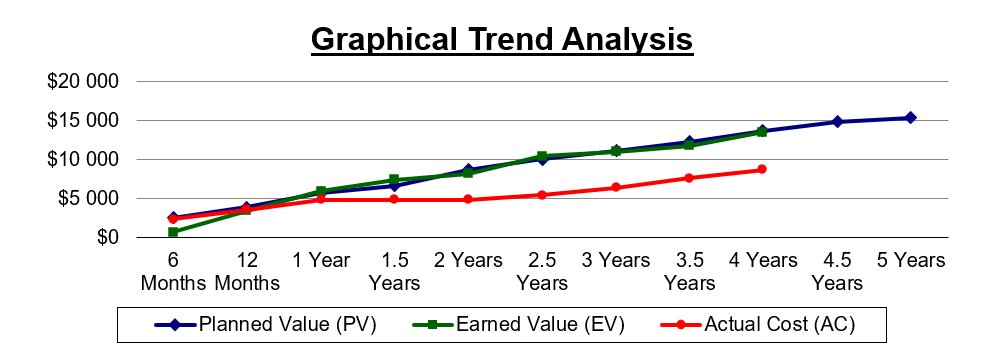

Earned value analysis

The project as at now is in its fourth year. The Estimated Actual cost (8600M) is less than the budgeted cost (13500M) by 5100M. However, the project records a 94% cost success rate. The schedule of the project remains on course as the project is completed within five years. As the graphical Trend Analysis indicates, the actual cost is less than the Planned Value at any time. Hence, the management negotiation with private landowners has significantly reduced costs. It is crucial to note that all costs in millions of HK $. The following table indicates the project performance as of the fourth year.

The work commenced in July of 2009 and as of July of 2013, 4 years had elapsed. The earned value was HK $ 13.5 Billion. The schedule variance as of July 2013 (today) was HK $ -200M as shown in Graph above. This means the project is delayed a little bit. The cost variance as of July 2013 (today) is HK $ -600M. This means the actual cost is less than the budget. The project spent much less than planned because the route of the railway track was slightly reduced after Mass Transit Railway negotiated an agreement with some landowners. The trend is that the project is behind schedule, but the actual cost is significantly less than the budget. This is because tunnelling and over groundworks spent significantly, less than what was planned because of a shorter railway route (Chase & Aquilano, 2006).

Project Change Control Procedures

In WIL, project change is authorized through change orders. The project manager keeps track of them and reports on them to stakeholders at all levels of the project (AGCA, 2003, 39). Changes are often caused by a change in the clients’ requirements, changes in local authority regulations, correcting errors in the specifications, unavailability of specific materials or equipment, and new technology. Minimizing misunderstanding due to change is the responsibility of the project manager. Requests for change should be detailed, including the time and cost estimates for making the change, and the period for responding to the change request.

In WIL, the change procedure is the responsibility of the project manager. As far as reasonably possible under the contract agreements, subcontractors are supposed to fulfil the terms and conditions of their contracts. If a subcontractor is unable to do so, they are required to communicate with the project manager, who will then decide what level of change (if any) can be allowed from the original requirements without compromising project schedule, budget or quality (MTR, 2013)

Evaluation of the Completed Project

In project evaluation, the institutional environment and the interests of the stakeholders are taken into consideration (Haezendonck, 2007). The WIL project is progressing in terms of its three objectives, namely performance/quality, cost and time. Judging by the parts of the project that have been completed, it is fair to say that they meet the required quality. This can be determined from the completion of the David Trench Rehabilitation Centre, the Kennedy Town Swimming Pool and the breakthrough of the railway tunnel from Sheung Wan station to Kennedy Town station, signalling the substantial completion of the tunnelling process (MTR, 2012b). These segments of the project amount to two-thirds of the core project, thus an accurate evaluation of the performance and quality of WIL must await its completion in 2014. Therefore, it is fair to state that the MTR West Island Line project is substantially along the path to its performance/quality goal of providing a fast, reliable commuter service to residents of the Western District of Hong Kong Island by the end of 2014. It is also crucial that it does not exceed the target budget of HK$ 15.4 billion, and 6,600 employees (Reiss, 2007).

Conclusion

The WIL project is following the transport policy of the Government, according to which the railway system is to be the backbone of the transport system. The additional three new stations will ease the road traffic congestion in the vicinity. The project, once completed, will connect the Western district to the Central business district.

The residents of the Western district have long been waiting for an alternative transport system, and WIL will put an end to their wait. Further, numerous employment opportunities have been created that have helped the natives. The properties situated along the railway will have a value appreciation.

Recommendation

Though the company is already doing some community works, the quantum of such acts should be increased. Another recommendation is that the company should be very particular about the environment. It should formulate a policy wherein. A tree should be planted for each tree that has been cut to make way for the project. This way, the company would be maintaining an ecological balance.

Apart from the proposed Information centre, the company should plan to construct a museum also. The museum should portray the history of Hong Kong’s transportation system and MTR’s contribution in bringing it to today’s standard.

Reference List

AGCA 2003, Guidelines for a successful construction project, The Associated General Contractors of America/American Subcontractors Association, Inc. /Associated Specialty Contractors.

Brown, M 1998, Successful project management in a week, Hodder & Stoughton, London, Great Britain.

CEDD (Civil Engineering and Development Department) 2009, Enhanced use of Underground Space in Hong Kong, Feasibility Study (Executive Summary), Geotechnical Engineering Office, Civil Engineering and Development Department.

Chase, B.R. & Aquilano, N.J. 2006, Operations Management for Competitive Advantage, McGraw Irwin, New York.

Gray, CF. & Larson, EW 2008, Project management: The managerial process, 4th edn, McGraw–Hill Education, Singapore.

Haezendonck, E 2007, Transport project evaluation, Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton, USA.

Johnson G, Whittington C & Scholes, K 2011, Exploring Strategy Text & Cases, FT Prentice Hall, New York.

Kay, J 1993, Foundations Of Corporate Success – How Business Strategies Add Value, Oxford University Press, London.

Lock, D 1996, Project management – 6th edn, University Press, Cambridge, Great Britain.

Lockyer, K & Gordon, J 1996, Project management and project network techniques, 6th edn, Prentice Hall, Great Britain.

Manfredonia, B, Majewski, JP, & Perryman, JJ 2010, Cost estimating. Web.

MTR 2009. Project Agreement signed for MTR West Island Line, MTR Press Release. Web.

MTR 2011. Over 1,500 jobs offered in MTR Job Fair, MTR Press Release. Web.

MTR 2012, MTR West Island Line one step closer to reality, MTR Press Release. Web.

MTR 2012b, West Island Line Project enhances connectivity at Sands Street, Kennedy Town, MTR Press Release. Web.

MTR 2013, Key Information. Web.

Orr, RJ & Tchou, J 2009, Project viability screening: A method for early-stage merit-based project selection. Collaborator for Research on Global Projects at Stanford University, California, USA.

Reiss, G. 2007, Project Management Demystified, Routledge, New York, NY.

Sadler, B 1988, ‘The evaluation of assessment: post-EIS research and process development’ in Environmental impact assessment: theory and practice, ed P Wathern, Unwin Hyman, London.

Schwalbe, K. 2013, Information Technology Project Management, Course Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Skinner, KS 1999, Geomorphologic post-project appraisal of river rehabilitation schemes in England. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, 309 pp.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2