Introduction

Globalization is an aspect that has changed the way national and international businesses are carried out; it is an aspect that has totally removed barriers between countries, encouraging cross-national business to take place. At the same time, globalization has encouraged most companies, specifically from developed countries to initiate business projects in developing countries. The result of all these is the presence of many multinational companies (MNCs) in many countries of the world especially the developing countries.

Managing across culture is a product of globalization, that expatriate from a foreign culture moves to a totally new culture and is required to manage people from diverse cultures and backgrounds, totally different from his or hers. Many have found the experience challenging, whereby majority have succeeded and at the same time, majority have failed. Managing across cultures requires adjustment to numerous conflicting or competing cultures while maintaining one’s culture, it requires understanding other people: their culture, their way of doing things, their way of management, and generally how they want to things (Christian Dior Limited, n.d).

Christian Dior Limited: American Company in Japan

Christian Dior Limited is a company that was established in 1946 (Christian Dior Limited, n.d). The American company specializes in manufacture and sale of different kinds of apparel accessories in different parts of the world (Christian Dior Limited n.d). Its first shop was opened in New York in 1949 and in 1997, the company moved to Japan market (Christian Dior Limited n.d). The company, which recruits employees from different countries, is taken to employ a workforce in excess of fifty five million (Christian Dior Limited n.d). Therefore, the essence of this paper will be to explore the concept of cross-cultural management specifically with regard to Christian Dior Limited in Japan market where majority of employees come from USA and Japan.

National cultures

Nations of the world show many differences than similarities with regard to culture. Culture can be explained to be value system of any given society that majority of that society’s population share. Cultures in general affect both physical and social environment, thus the principle practices in the society seem to take a certain pattern that will bring about cohesion and sustainability in the society (Hofstede 2001). In understanding different cultures, it has become important to study history of the particular concerned societies.

Japanese are said to proud of their tradition (culture), which they have been able to maintain within fierce influence of western societies. Although largely seen as a secular society, Japanese most values have been drawn from religion that greatly has emphasized harmonious relationships with other people (Genzberger, 1994); Japanese always value relationship especially harmonious relationships. Japanese values and to extent, culture has originated from five main traditions: traditional religion of Shinto, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism adopted from China (Genzberger, 1994).

Shinto values require Japanese to establish and exist within harmonious relations especially with others. Confucianism on its part comes out as a social code for behaviors to exercise; the element requires Japanese to have obedience to the seniors and those superior, thus to exercise paternalistic treatment of the subordinates. With regard to scientific materialism, Japanese have an inclusive attitude toward competing philosophies that enable them to contradict to most of Western ideas since most Westerners have exclusive attitude (Genzberger, 1994).

Hofsede’s cultural dimensions for Japan and America

Hofstede is famous for his words that tend to present culture as being made up competing forces that tend to interfere with the normal practices of the society rather than bringing cohesion (Hofstede n.d, p.1). According to Hofstede’s assertion, it has become apparent that international management of cross-cultures involves operating and working within competing and conflicting cultures. Numerous researches have been done with regard to nation’s cultures and the way they affect international management in business environment.

For example, related studies to Hofstede’s study include GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) Project and Trompenaar’s 7D cultural model (Aswathappa and Dash, 2007). Observation and suggestion propagated is that, for international managers who understand these concepts or models well, their chances of succeeding in international management are high (Aswathappa and Dash 2007).

Globe Project study postulate that, there are nine cultural dimensions that characterize different societies and separate them from one another. These cultural dimensions include aspects to do with being bold, futuristic, and socially devoted, as well as being sensitive to matters related to gender, personality, achievement, and power among others (Aswathappa and Dash 2007, p.29). Each of these elements characterizes each society differently and observation made is that each society differs from each other based on these elements.

The second study was done by an European researcher, Trompenaars, who after carrying out research on over 15,000 managers concluded that, there were seven dimensions with regard to cultural differences, which entailed looking at the society in form of individual members as well as the whole society, historical perspectives and future trends and aspects that are within the society as well as those that transcend beyond the societal boundaries. Again, Trompenaars used these cultural dimensions to categorize countries differently with regard to their cultures.

The most celebrated work is that done by Geert Hofstede, a social scientist from Netherlands, whose five cultural dimensions revolutionalized the field of international management. Hofstede identified five cultural elements, which he used to study and describe cultures of different countries. Power distance element expresses that inequality with regard to power exist in different societies where to some societies power distance is high between rulers and subjects while in other societies power distance is low (Hofstede n.d). On the other hand, individualism element posits that individualism and collectivism differ among societies.

For example, individualistic societies’ people are self-centered, only concerned with their own welfares, but collectivistic society’s in-group feeling is strong, and achievement is meaningful when group participation is observed (Hofstede n.d). Masculinity element is compared to feminism element, which largely describes and explains how different societies distribute gender roles (Hofstede, n.d). Uncertainty Avoidance has to do with how different societies tolerate anxiety about time and future. Some societies demonstrate high uncertainty avoidance index while other societies show low index (Hofstede, n.d) Lastly, Long-term orientation is an element that came later after studies were conducted in China and it explains how some societies tend to be short-term oriented while others are long-term oriented (Hofstede, n.d).

Hofstede dimensions for Japan and America

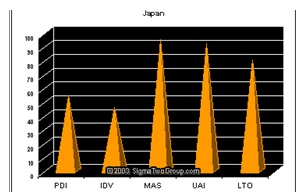

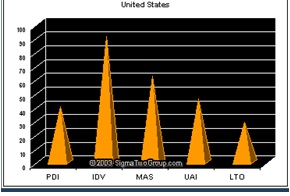

Managing in Japan

Compared to USA with regard to Hofstede cultural dimensions, Japan is seen to exhibit high rates in virtually all the dimensions. What does this say about Japan? In short, what the graph shows is that Japan believes that: inequality in society is somehow normal; people should be dependent on a leader; conflicts in any situation or circumstance should be avoided; laws are critical and should be adhered to; and consensus is always the best method to adopt. In addition, group decision making, group achievement and group responsibilities are highly valued; expression of emotion in any situation is accepted; emphasis in organizations tend to be on compromise; harmony and adjustment is always good and encouraged; and managers tend to be fatalistic (Aswathappa and Dash, 2007).

Managing across culture

Richard Lewis, author of ‘when cultures collide: managing successfully across cultures’ note that different cultures for different nations can be summarized into three main groups: task-oriented, highly organized planners and people oriented (Lewis 2000). On their part David Ahlstrom and Garry D. Bruton observe that understanding culture is fundamental to understanding many of the differences in business at global level (Ahlstrom and Bruton 2009).

The authors see culture as acquired knowledge that people utilize in interpreting occurrences and events. The knowledge acquired in turn influences the principles, thoughts, and behaviors of those people, all of which are seen to be reflected in the wider spectrum of the society (Ahlstrom and Bruton 2009). In reality, managing culture in a diverse environment is not an easy task but the key or strategy is for the manager to facilitate some level of uniformity (Schneider and Barsoux, 2003).

Numerous problems have been identified to emanate with regard to cross-cultural management problems with regard to differences in the value systems. This particular problem results due to the fact that cultures are different and greater degree of difference is seen in value systems, which are intertwined in cultures and translated into action. The point here is that people having different culture backgrounds approach a particular similar problem in different ways due to different orientation of different value systems (Bhattacharyya 2010).

Problems with regards to preconceptions and stereotypes, stereotyping among people is essentially used to simplify and classify individual’s assumptions based upon which they derive their inferences by observing certain evidences and characteristics (Branine, 2010). With regard to cross- cultural teams, stereotyping manifests itself through people stereotyping other peoples’ qualities and capabilities in the most negative way. In most cases self-fulfilling prophecies motivate individuals to communicate with people in a particular manner that bring out the trait, others expect them to possess (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

The third problem has to do with individual decision-making and problem solving; in most cases, people from different cultures possess different strategies or methods as to how to solve problems, which in turn creates problems in the way an organization should carry out its operations (Bhattacharyya, 2010). Differences in decision-making perspectives arise due to differences in educational backgrounds, work experiences, and culture-based value systems, which all lead to different approaches to a problem thus encouraging problems (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

Observation prevalent include team members taking decisions on their own without encouraging participation of others, others members favor participative approach, others may put much trust in rational decision making where they prefer to collect enough information and necessary resource input before arriving at decision, while others may generally have feelings to have quick-fix approach (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

The other problem has to do with communication, where most problems in cross-cultural teams resulting from lack of, or poor quality communication. In cross-cultural groups most problems to do with communication revolves around language and non-verbal behavior (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

As English is the prevalent and widely spoken language it may come out that some people find it totally uncomfortable to communicate or express in English instead favor the local and prevalent language to communicate in irrespective of the different background of other colleagues. At the same time, non-verbal behaviors; for instance, gestures has been categorized as an important aspect of communication. Gestures and body languages vary across cultures. Misinterpretation of verbal and non-verbal has led to further misunderstanding between different cultural backgrounds (Bhattacharyya, 2010).

Different cultures adopt technology differently; for instance, in modern society, meetings are increasingly taking place between team members using technologically enabled communication system such as telephones, video-conferencing, emails, or even online chat (Bhattacharyya 2010); 6) problems originating from differences to time, where with regard to different cultures in an organization time perception varies across culture. For instance, organization’s members might prefer to have monochromic attitude where they prefer to do one task at a time, while in polychromic attitude, team members may prefer to do many tasks at the same time (Warner and Joynt, 2002).

How to succeed in managing cross-cultural groups

Adler has observed that successful cross-cultural teams do not in essence ignore their diversity; rather, they manage it (Hamilton 2007). As such, to effectively manage diversity, Adler suggests for the following: there is need to recognize the differences that exists in terms of cultures; electing members for their task-related abilities where suggestion is that members need to be ‘homogenous’ in terms of ability and heterogeneous in attitudes; there should be a common a common purpose, vision or super ordinate goal that goes beyond individual differences; there should be avoidance of cultural dominance; there should be initiatives that encourage respect to everyone; and there should be seeking of high level of feedback (Hamilton 2007).

London and Sessa (1999) note that, to be successful as cross-cultural manager, the following has to be met: ability to facilitate work in a diverse setting; be able to generate the perception of shared culture motivate; sustain; and be able to successful facilitate cross-cultural teams; further there is need to foster productive relationship between different business units of the organization having different cultures; ability to successful select and carry out evaluation of staff from different cultural backgrounds (London and Sessa 1999).

At the same time, successful cross-cultural managers recognize cultural differences in the organization, respond to the local issues, make smooth transitions between tasks and jobs that involve and include different people and spanning different cultures. This is in addition to adapting to the environment, and successfully managing between extremes by collaborating and negotiating with people who possess different values and beliefs about goals and overall business behaviors (London and Sessa 1999).

The author finishes by noting that, in general, cross-cultural management success depends on cultural sensitivity by the manager where communication and decision-making becomes key strategy to success (Wilson, Hoppe and Sayles, 1996). In this case, the manager should be fully acquainted with the diverse cultural practices and needs in order to effectively meet the needs of the entire organization. This is due to realization that different culture will exhibit different practices that may or may not appeal to other cultures. Thus, being sensitive to the cultural differences will create an opportunity of cohesion in the institutions that habour people from different cultures.

According to Adler (1997), successful cross-cultural managers need to have or possess the following aspects or characteristics, which in large part determine their success or failure. Cross-cultural management requires managers, who have the ability to employ cultural sensitivity and diplomacy that have the ability and capacity to foster relationships that create strong and meaningful respect for all parties involved in the organization and communicate in the concise way bringing satisfaction and understanding to almost everybody.

This is in addition to ability and talent to solve cultural problems synergistically and lastly strong negotiation skills (London and Sessa 1999). Further, Merode (1997, cited in London and Sessa 1999) notes that successful cross-cultural or multi-cultural managers should be able to motivate cross-cultural teams, have the capacity and ability to conduct cross-cultural negotiations, have the ability to recognize the influence of culture on organization’s business practices; and be able to select and evaluate staff in different cultural setting. They should also be good and trained in managing information across multiple time zones, be able to integrate local and global information for multisite decision-making, and be able to stimulate information sharing within the organization (London and Sessa 1999).

On their part, Steers, Sanchez-Runde and Nardon (2010) offer key strategies that global managers in multi-cultural setting should follow. The strategies, which are put forward to enhance cultural awareness, include but not limited to:

- developing a learning strategy that has the capacity to guide both short-term and long-term professional development as a multi-cultural manager.

- The manager needs to develop a basic knowledge of how different cultures work, what makes them unique, and how the managers can work successfully across such environments.

- Develop strategies of working in harmony with managers from other cultures who may have different information opinion and view their roles and responsibilities in unfamiliar ways.

- Develop cross-cultural communications skills.

- Develop an understanding of leadership processes across cultures, and the way managers can work with others to achieve synergistic outcomes.

- Develop knowledge of how cultural differences can influence the nature and scope of employee motivation, as well as what global managers might do to enhance on-the-job participation and performance.

- Lastly, develop effective negotiating skills and an ability to use these skills to build and sustain global partnership (Steers, Sanchez-Runde and Nardon 2010).

Conclusion

Globalization is an aspect that will continue to characterize many organizations. Cross-cultural management will remain part of globalization where managers from different cultures will assume roles of management in different cultures. Different nations’ cultures have strong impact on the societies in that they strongly influence how key institutions of those countries behave and act. At the same time, nationals’ cultures impact on overall national behaviors of citizens and these modifications of behaviors are translated into business and management practices. According to Hofstede, international management is challenging and it requires international managers to adequately learn and study cultures of other societies especially those they are moving to. His five cultural dimensions offer a solid foundation upon which international managers can study other cultures.

When United States of America and Japan cultures are compared, they show numerous differences which international managers moving to Japan have to be versed with. By using Hofstede dimensions, it can be summarized that Japan shows high distance with relation to power as compared to USA. In addition, Japanese is collectivistic as compared to America’s individualistic nature, Japan has high masculinity as compared to USA where women in the society are still not given equal chances to compete with men fairly, and Japan tends to show high degree of Long-term orientation as compared to USA. In general, managing across cultures requires the individual to develop and train in cultural sensitivity, have effective communication mechanisms to use across different cultures, have conflict resolution skills, possess adequate negotiation skills, ability to provide and lead realization of organization’s goals using talents that borne out of cultural diversity.

In general, international opportunity should provide an individual with chance to develop cultural sensitivity and cultural tolerance (Solomon and Schell 2009). Lack of understanding nations’ cultures can lead to outright failure by any manager who might ignore key aspects to be learnt. Japan management culture has offered many Americans managers numerous challenges, as they have to merge; they most widely held individualistic elements and Japanese collectivism elements. What is needed is for international organizations to design effective cross-cultural management manuals, which can guide their foreign managers. At the same time, managers are required to learn and train in matters of cultural tolerance, cultural audit, or even cultural evaluation, also adjustment programs to foreign cultures need to be integrated with the needs of the manager as they are dictated by the foreign environment. Success in foreign country results from effective strategies that bring key stakeholders in the process of formulation and implementation.

Reference List

Ahlstrom, D. and Bruton, G. D., 2009. International Management: Strategy and Culture in the Emerging World. OH, Cengage Learning. Web.

Aswathappa, K. and Dash, S., 2007. International Human Resource Management. New Delhi, Tata McGraw Hill. Web.

Branine, M., 2010. Managing Across Cultures: Concepts, Policies and Practices. NY, Sage Publishers.

Christian Dior Limited. N.d. Christian Dior. Web.

Genzberger, C., 1994. Japan business: the portable encyclopedia for doing business with Japan. CA, World Trade Press. Web.

Hamilton, C., 2007. Communicating for Results: A Guide for Business and the Professionals. OH, Cengage Learning. Web.

Hofstede, G., N.d. Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions. Web.

Hofstede G., 2001. Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. NY, SAGE. Web.

Lewis, R. D., 2000. When cultures collide: managing successfully across cultures. UK, Nicholas Brealey Publishing. Web.

London, M. and Sessa, V. L., 1999. Selecting International Executives: A Suggested Framework and Annotated Bibliography. Center for Creative Leadership. Web.

Schneider, S. and Barsoux, J., 2003. Managing across cultures. NY, Prentice Hall/Financial Times.

Solomon, C. M. and Schell, M. S., 2009. Managing across cultures: the seven keys to doing business with a global mindset. New Delhi, McGraw-Hill Professional. Web.

Steers, R. M. and Sanchez-Runde, C. J and Nardon, L., 2010. Management Across Cultures: Challenges and Strategies. UK, Cambridge University Press. Web.

Warner, M. and Joynt, P., 2002. Managing across cultures: issues and perspectives. NY, Thomson Learning.

Wilson, M., Hoppe, M. H. and Sayles, L.R., 1996. Managing across cultures: a learning framework. NY, Center for Creative Leadership.