Introduction

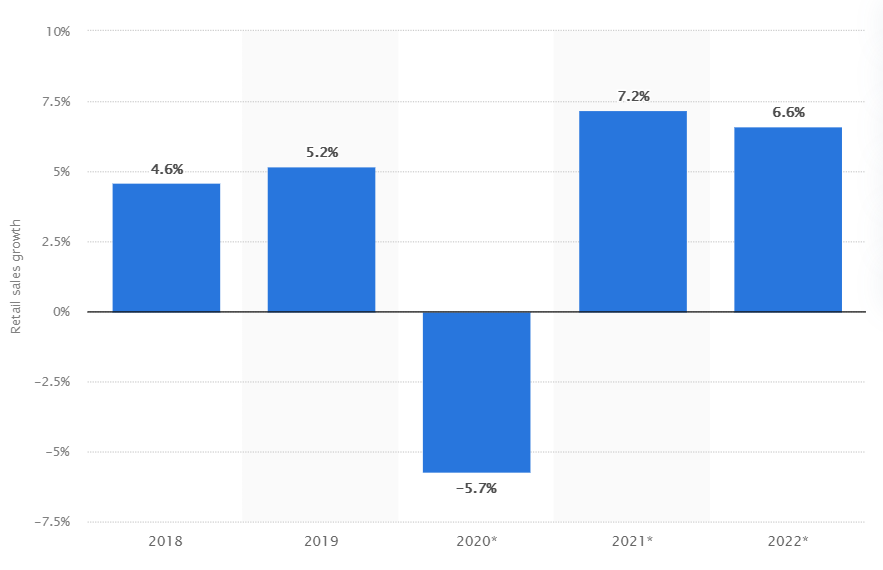

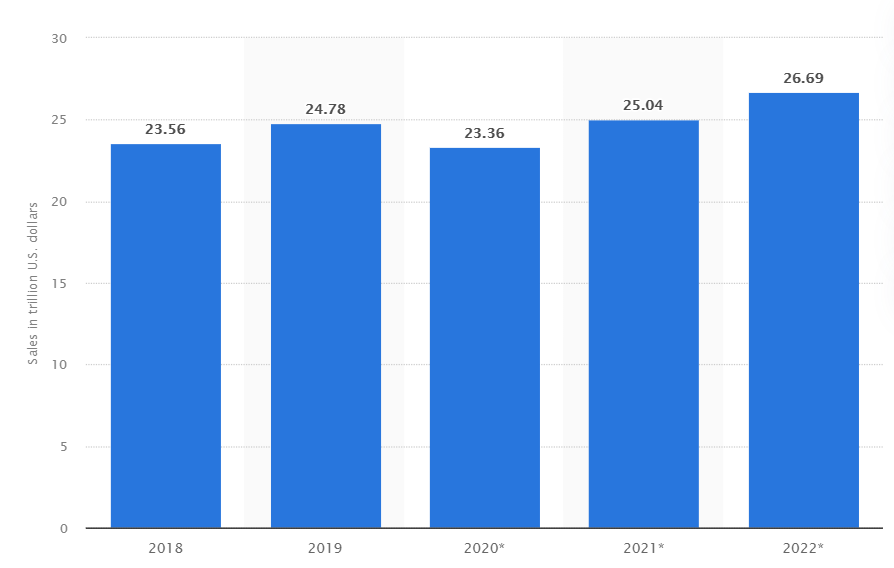

Retail sector remains of the drivers of modern economy because of its scape, scope, and vital status for the life of society. According to the Statistic Research Department (2021), the amount of global retail sales has reached the level $25 trillion with $19.2 trillion in physical turnover and nearly $5 trillion in e-commerce operations. Figure 1 shows the dynamics of the world’s retail industry growth, including the projections for the year 2022. As it becomes clear, this sector remains in the state of constant development with the demand growing on an annual basis. Nevertheless, the market faced a challenge of unprecedented magnitude in 2020 when the global sales rates dropped by nearly 6%. On the scale of the global retail turnover, this decrease accounts for hundreds of billions dollars-worth of financial losses.

The reasons for this standalone fall of retail sales are evident in the context of global affairs. More specifically, the year 2020 is associated with the greatest challenge faced by humanity in recent decades. The novel coronavirus pandemic has put the world to an ultimate test. Through active travel and intense international exchange, the disease penetrated most of the world’s communities, leading to the most considerable pandemic in recent history. In response to the emerging challenges and in an attempt to prevent the further widespread of COVID-19, the world’s authorities relied on the containment approach (WHO, 2021). Under these circumstances, the world’s economy was partially paralyzed, and the normal lifestyle of the population was disrupted (Wojcik & Ioannou, 2020). These challenges encompassed an array of spheres, as no corner of the planet remained unaffected by the outbreak. In addition, the pandemic had a strong impact on most spheres of human activity (Sonn et al., 2020). Entertainment facilities, schools, universities, and stores had to be closed, as billions of people remained confined during lockdowns (Inn, 2020). The normal ways of living became disrupted, and the world’s infrastructure had to readjust.

This dissertation emphasizes smart cities’ retail industries as the key point of interest in regard to the pandemic response. According to IMD (2021) the Smart City Index currently comprises 109 entries. All these agglomerations make a considerable contribution to the global economy by utilizing progress to increase the rates of economic growth and sustainable development. In its general understanding, a smart city is an urban territory, which utilizes the modern expertise and technological capacity of humanity in order to become adjusted to the current demands of their communities (Caragliu & Del Bo, 2018, p. 374). In other words, smart cities represent a new step of the urban evolution in the spirit of the time. As such, it can be expected that the exact way in which the pandemic affected these territories may prove to be highly particular (Allam & Jones, 2020). Smart cities are characterized by the extended application of modern technological advancements, which suggest that they may have a better potential in terms of the response to the pandemic (Sonn et al., 2020). Moreover, implementing these smart ideas requires a certain degree of flexibility and adaptability to current challenges by default.

The retail industry has experienced a colossal impact of the pandemic and its aftermath. According to Loske (2020), the authorities’ desire to impede the widespread of the virus inevitably disrupted normal economic relations. In addition, the pandemic transformed the purchasing behavior of retail customers. From one perspective, the brick-and-mortar format saw an inevitable decrease in turnover under the COVID-19 restrictions (Dannenberg et al., 2020). As Figure 2 shows, the decrease across 2020 amounted to over $1 trillion. On the other hand, the closure of traditional leisure venues, such as restaurants and bars, liberated up to 30% of the consumers’ monthly spending that was reallocated to grocery retail purchases (Goddard, 2020). Nevertheless, in order to utilize this economic influx, retail companies needed to perform a shift toward the online segment of retail. Such a transition is demanding in terms of the technological capacity of both retailers and consumers. Thus, smart cities had a better starting point in terms of mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on retail. This research aims to investigate whether New York, Dubai, and Singapore were able to utilize their potential, as well as the exact instruments deployed.

Theoretical Perspective

Apart from the immediate epidemiological properties of the virus, scholars are actively engaged in the discussion surrounding the pandemic and its effect on the economy of the 21st century. More specifically, the contemporary body of knowledge seeks to investigate how the disruptive potential of COVID-19 factors into the new reality of today (Costa & Peixoto, 2020). Even in smart city studies, the main focus is centered on the medical perspective, such as the healthcare system’s capacity to withstand such challenges effectively. The prevalence of such a perspective is natural, as COVID-19 is a medical issue, most of all. Furthermore, the global priority is rightfully set at researching the physical aspect of the virus, as well as the way of its treatment and eradication to save lives.

The coronavirus and corresponding restrictions disrupted the normal way of living and undermined global economic growth. This effect renders COVID-19 a global interdisciplinary phenomenon with an extend range of influence (WHO, 2021). As the pandemic is also a recent development, the coverage of its particular aspects is insufficient in the current body of literature, leaving evident research gaps. As for the smart city studies, researchers such as Inn (2020) and Del Carmen Olmos-Gómez (2020) note that the focus of these communities’ technological capacity use has been on the identification of new COVID-19 cases and prevention of new ones. However, considerably less research is done in regard to the smart cities’ response to the pandemic’s challenges in retail (Guven et al., 2020). Thus, it is required to investigate the exact degree, to which COVID-19 affected retail as a disruptive factor. The theoretical examination of this perspective will provide a framework of reference for further comparison with the practical implementation of the smart city potential in the age of COVID.

Policy Perspective

Amid the outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease, governments of the world have been devising new policies to address this emerging challenge. While the World Health Organization (2021) has provided the global authorities with continuously updated recommendations in regard to the pandemic response, each nation has the agency to pursue individual policies. In this regard, the general direction of the response protocols has been executed along similar lines in most cases. More specifically, local and national authorities attempted to contain the virus by minimizing the direct contact between people. Non-essential industries experienced prolonged closures and many organizations had to opt for a work-from-home system whenever possible. However, effective response protocols require further information regarding their effect and potential consequences on specific areas of activity (Sonn et al., 2020). This research will introduce a new perspective on how smart city potential can be utilized for the maximum efficiency-security nexus policy-wise.

Under these circumstances, retail companies had to develop new internal policies that would allow them to survive in the new reality. Within smart cities, the reliance on high-tech solutions is an obvious avenue, but the exact ways of their implementation in company policies remained unclear (Gupta et al., 2020). As such, most attempts appear to have been mostly experimental with subsequent modification based on the feedback and outcome. Therefore, more profound research into the pandemic response in smart cities’ retail segments will contribute to the development of efficient policies on corporate and national authority levels.

Practical Perspective

From the practical point of view, an enhanced theoretical framework, combined with more efficient policies, will provide better, informed solutions to address the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic. In fact, the pandemic has had a tangible effect on society, meaning that this discussion cannot be limited solely to theoretical findings (Bhatti, 2020). The practical dimension of the research and its contribution will revolve around the retail sectors of the world. Having devised a comprehensive framework of reference that incorporates the current body of knowledge, the study is to review the implementation of smart city response protocols in the post-pandemic retail industry. Based on this data, it will be possible to assess the degree, to which the retail industries of the three smart cities under review managed to cope with the aftermath of COVID-19.

Research Statement

The present study aims to answer the central research question with an emphasis on the retail industry of New York, Dubai, and Singapore: “How have smart cities dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic using smart technology?” In this regard, the proposed set of research objectives is as follows:

- What are the strategies smart cities use to deal with crisis?

- How did smart cities use these strategies or others to mitigating the impact of the pandemic on the retail industries?

- Devise evidence-based guidelines for the smart city retail industry’s response to a pandemic scenario.

Benefits of the Study

This research is expected to yield positive results in the fields of theory, policy, and practice. First of all, in the course of the analysis, a comprehensive theoretical framework is to be produced, looking at how smart cities respond to crisis and specifically how they responded to the pandemic. Second, the practical implementation of the theoretical discussions is to be examined and analyzed, synthesizing a set of guidelines that will enable efficient measures in the subsequent, hypothetical pandemic scenarios. The findings can be extrapolated to the policy level by individual organizations and authorities, as they are based on the factual evidence obtained from the lessons of the present pandemic.

Dissertation Outline

This dissertation addresses the development of the response procedures within Smart Cities’ retail industries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chapter 1 provides a general overview of the topic, while emphasizing the multi-tier value of the study for theory, practice, and policies. Chapter 2 review and synthesizes the contemporary body of knowledge in order to establish a better understanding of the key concepts. Chapter 3 describes the study’s methodology selection. More specifically, it addresses the specific procedures undertaken, as well as the sample justification. Chapter 4 discusses the findings obtained in the course of the study, evaluating their value for the research field. Chapter 5 synthesizes the information provided within the dissertation with the purpose of drawing appropriate conclusions.

Literature Review

Smart Cities as a Concept of Urban Planning

At present, the concept of a smart city has become a subject of heated discussions. According to Lai et al. (2020), the 21st century introduces a new level of technological development. Its potential is immense, allowing new, advanced solutions to permeate multiple spheres of human life and activity. In this regard, smart cities become the pinnacle of high-tech urban planning of the century. More specifically, they implement an effective paradigm of advanced solutions in order to introduce a new level of comfort, safety, and convenience for their residents (Caragliu & Del Bo, 2018). Ismagilova et al. (2019) add that “smart cities employ information and communication technologies to improve” an array of spheres (p. 90). The purpose of such frameworks is related to better transportation, economy, environment, and government interaction. In other words, they make the modern way of living smart, which is regarded as a partial equivalent of efficiency.

Smart city is a broad term that encompasses other ways of addressing these urban territories. Ismagilova et al. (2019) present such a list of synonyms as “Digital City, Information City, Intelligent City, Knowledge-based City, Ubiquitous City, Wired City” (p. 88). These nominations reflect the technological reliance and superiority which is embedded in the term. For Silva et al. (2018), smart cities are the manifestation of a concept known as the Internet of Things (IoT). It implies a new degree of convenience, introducing the enhanced availability of services and goods for the population. Residents can use modern technology to facilitate their daily errands and complete them more efficiently. Businesses benefit from expanded markets and new avenues of customer interaction. In turn, regulators implement better control protocols over various activities that theoretically should lead to higher levels of safety and transparency within society (Silva et al., 2018). These factors outline the primary advantages of the smart city planning that guides the development of the concept.

At the same time, a logical question arises in light of these facts. If the concept of smart cities is so superior, why does it remain an innovation that is not implemented universally? Modern researchers address this question by outlining the primary impediments that prevent most cities from obtaining a “smart” status. Silva et al. (2018) note that the concept remains in the state of evolution and improvement. In spite of its evident advantages, many cities face serious challenges on their path toward the implementation of a smart framework. These challenges are related to governing, economic, and technological barriers. The third category is particularly important, because technology and smart cities are integral to each other. Lai et al. (2020) add that smart cities are expected to adhere to high standards. Otherwise, the urban territory will not exhibit the required level of technological advancement. In terms of specific features, Ahad et al. (2020) refer to the IoT, artificial intelligence, and wireless sensor networks as the primary descriptors of the smart city technology. All these elements are to exist in a nexus for the city to reach the expected level of efficiency.

Based on the contemporary findings, it is possible to outline the general perception of a smart city. Such urban territories are characterized by the dominant presence of high-tech solutions in its organization. In it, modern advancements facilitate the lives of the residents through efficient means of communication, as well as accessible products and services. Smart cities create an urban environment that addresses the challenges of the 21st century and redefines the understanding of a city in accordance with modern standards. Thus, they aim at better efficiency of trade, economy, and social relations. However, the implementation of such frameworks is a costly endeavor that includes high standards of technology utilized. Economic and political factors often serve as impediments to the new paradigm of urban planning, but technological insufficiency remains the leading barrier.

Smart Cities’ Response to a Crisis

The framework of smart cities is designed to make their residents’ lives better and safer on a daily basis. However, the contemporary landscape remains unpredictable, as new challenges emerge at a rapid pace. In this regard, it appears interesting to investigate smart cities’ resilience in the face of a crisis. Smigiel (2018) states that this idea is highly relevant for urban planning in Europe. His discussion is centered around the Italian experience in applying smart city strategies to resist the impact of various crises. According to Smigiel (2018) the resilience is highly dependent on the institutionalization of the smart principles. In other words, they are to be actively and correctly utilized by local authorities to mitigate the negative effect. It creates a new level of the private-public nexus within a smart city, ultimately yielding benefits for all parties involved. Thus, smart cities show a better degree of preparedness and adaptability potential only when the perspectives of authorities and the public are aligned.

Among the various crises faced by smart cities, the current COVID-19 situation has been one of the most serious challenges in modern history. The subsequent studies explore the high-tech instruments of smart cities in the face of the pandemic on a more profound level. For example, Tan Lii Inn of the Penang Institute begins the discussion with the early stages of the pandemic. At that point, an advanced Artificial Intelligence-based algorithm was able to predict the negative development of the unusual pneumonia outbreak in China (Inn, 2020). According to the author of the study, smart cities are able to handle such cases in a more effective manner. They possess an arsenal of valuable instruments, such as thermal cameras, facial recognition software, and Internet of Thing sensors. Interestingly, once the population started wearing masks, the efficacy of facial recognition dropped by more than a half. However, smart cities are able to readjust this equipment to control whether their residents adhere to the safety protocols in public spaces. Thermal sensors also found a new way of practical application, checking people’s temperature, as fever is one of the first signs of coronavirus disease. Ultimately, the general trends suggest that smart cities were able to reorient their technological means and adjust them to the new reality.

The next articles review the application of smart city technology in the context of the pandemic. Sonn, Kang, and Choi (2020) rely on the evidence from the Asian region in order to highlight the opportunities present by modern advancements in the age of COVID-19. According to the authors of the study, smart cities demonstrated a better level of preparedness to track and eliminate the threats posed by the new virus. The transportation system is said to be one of the crucial elements of smart city infrastructure. In such territories, policy-makers were able to trace the movements of confirmed COVID-19 patients using the data obtained from their electronic transportation cards. At the same time, mobile service providers provided sufficient resources as well through the dense distribution of transceivers across smart cities. Sonn, Kang, and Choi (2020) note that in the past, the corresponding infrastructure used to be devised in the aftermath of pandemics as a part of lessons learned. Today, smart cities possess a valuable technological arsenal, which means that the required infrastructure is already implemented. However, the key challenge consists of utilizing it correctly in order to ensure the survival of vital spheres.

Several pieces of research introduce specific frameworks that can be and are used by the smart cities. Soyata et al. (2019) indicate that such models represent a nexus of technology and policy transformations that account for better adaptability at the time of crisis. For them, the initial phase of the crisis response consists of engaging the first responders and experts in corresponding fields. Through their expertise, it is possible to establish a better assessment of the data needs. Documents, accounts, and expert opinions are subject to examination, upon the results of which the subsequent actions are made. Specifically, Soyata et al. (2019) propose the deployment of smart boxes with sensors throughout a city, reflecting the IoT principle. They will provide more precise data in regard to the crisis pattern that becomes combined with the aforementioned sources for better accuracy of evaluation. Finally, the next stage consists of the evidence-based solution integration that utilizes the data leverage obtained during the previous stages.

Another framework proposed by the contemporary body of literature is time-based, representing the four stages of the crisis response in smart cities. According to Sharifi et al. (2021), the first phase is planning and preparation. More specifically, it consists of building the resilience of smart cities in the face of a potential emergency. Smart technology, such as IoT and AI, are capable of analyzing the city’s infrastructure and residents’ behavioral patterns with enhanced precision. This information can be applied to the identification of the possible weak spots in the community. Once a crisis erupts, the phase of absorption begins, the purpose of which is to mitigate the first impact and keep the situation contained. The success of this stage determines how quickly the city can transition to phase three – recovery. Traffic monitoring, enhanced communication, and IoT help policy-makers mitigate the consequences of the outbreak in the long-term, returning the city to its normal functioning. At this point, the long-term solutions target the city’s adaptation to the new reality. The developed solutions become embedded in its regular activities, which, in turn, is related to the preparation phase, bringing the framework to a full circle.

Smart Cities and Retail through the Lens of the COVID-19 Pandemic

One of the smart cities’ objectives is to introduce modern solutions for the sustained development of their industries. Among these industries, retail occupies a special place due to its increased importance for agents of the economy. D’Hauwers et al. (2020) describe a data-driven approach to the modernization and enhancement of retail activities. According to their findings, the e-commerce has become an important factor for the industry, leading to a decrease in traditional retail sales. In this regard, data helps policy-makers and retails understand the roots of such a paradigm shift. Specifically, it provides insight into the changes of the consumers’ buying habits, explaining why they opt for the new formats. In the context of retail, a smart model implies the understanding of the customers’ needs and expectations, tailoring the industry policies accordingly. When the two perspectives align, consumers benefit from relevant services, whereas the industry sees an increase of profits and community support.

Among the various sectors of economy, the retail industry was one of the most affected by the pandemic’s onset and aftermath. The purpose of the safety measures implemented by most governments was to minimize direct human contact, thus preventing the infection from spreading. Evidently, normal retail operations became complicated under such circumstances. Bhatti et al. (2020) state that coronavirus disease had a profound impact on global retail trends. In this scenario, electronic commerce opportunities became a necessary, rather than mere convenience, for customers and sellers alike. Following the anti-pandemic procedures, both sides quickly came to realize the value of e-retail in the 21st century. Naturally, the implementation of electronic commerce networks was significantly simpler in smart cities, where digital literacy and technological capacity are increased.

Thus, the implementation of digital solutions and e-commerce instruments has been expected to be easier in smart cities. For them, the onset of the pandemic and corresponding restrictions have become the primary incentive of a more profound use of advanced technology on all levels. According to Nanda et al. (2021), the shift toward digitally powered platforms had been observed in retail markets for a considerable period before the pandemic. However, COVID-19 prompted decision-makers to accelerate their transformation processes, implementing technology assisted commerce in retail operations. These tendencies have been observed across all areas of retail, from grocery stores to real estate. This way, the use of digital technology becomes the key instrument of mitigating the aftermath of the global pandemic. Smart cities have better technical arsenals and increased levels of digital literacy that allow them to utilize these solutions more effectively.

For the retail sector, one of the most serious outcomes of the pandemic is related to the change in consumer behavior. The population, including the residents of smart cities, could no longer provide a similar level of demand on regular terms. First of all, customers lacked physical access to retail venues due to the pandemic-related restrictions. In many areas of the globe, residents could only leave their households on special occasions, for example, for vital purchases. Combined with the considerable decrease of the population’s purchasing power, this factor contributed to the major reduction of retail sales reflected in Figure 1. Under these circumstances, retailers sought new ways of engaging their consumers in a remote format. The IoT framework and digital platforms served as the primary enablers of e-commerce operations amid the pandemic. They allowed for a safer exchange of goods and services that complied with the authorities’ requirements. In smart cities, the adaptation became quicker because of the already high levels of digitalization. Another key difference consisted of the authorities’ willingness to promote advanced retail solutions on a policy level.

Conceptual Framework Synthesis

Overall, the synthesis of the current body of knowledge places the technological superiority of smart cities at the center of discussion. Thus, this principle is the cornerstone of research related to smart cities across various contexts. By default, such agglomerations possess an arsenal of advanced instruments that improve the daily lives of their residents. Smart technology enables efficient information exchange, service delivery, and communication. In addition, it renders such cities safer and convenient, as well. Nevertheless, its implementation is a costly endeavor in various terms, including the economic aspect, as well as the correct utilization of knowledge. This research will consider it as a central theoretical pillar that the key to resilience of the retail industry is the smart cities’ ability to adapt. In other words, it does not suffice to possess smart technology for an effective crisis response. Instead, it is essential to understand the exact aspects of the challenge to devise promising, smart solutions. Table 1 represents the envisaged framework of the crisis response synthesized through the examination of literature.

Table 1. Smart City Crisis Response Model.

Methodology

The previous chapters have introduced the scope and objectives of the present research, as well as the key themes that are associated with the impact of COVID-19 on retail in smart cities. The obtained findings serve as the basis for the subsequent discussion within the specified theoretical framework of retail industry’s response to the pandemic in smart agglomerations. Following this data, the present chapter introduces the specific methodology model that is the primary driving force of the research. The research design is presented, as suggested by the best practices within the contemporary body of academic knowledge. Next, the justification for the selected sample and scope of the study is provided, as well. The key objective of the chapter is to explain the logic behind chosen methodology, which relies on the theoretical framework specified prior.

Research Design

Within the framework of contemporary research practices, the key dichotomy of qualitative and quantitative research is observed. The differences between the two models of study are embedded at the fundamental level. According to Aspers and Corte (2019), the exact definition of qualitative research varies across different sources. However, they are united by the same ideas behind the formulations, which is why these authors define it as “an iterative process in which improved understanding to the scientific community is achieved by making new significant distinctions resulting from getting closer to the phenomenon studied” (Aspers and Corte, 2019). In other words, qualitative research aims to establish a better understanding of the entities and phenomena that are currently underrepresented and understudies within the body of academic knowledge. Simultaneously, quantitative research pursues a different agenda, being applied to known phenomena with the purpose of providing detailed knowledge on specific tendencies within them (Queirós et al., 2017). This method enables the application of various statistical analysis techniques that, for example, serve to quantify the prevalence of various factors. Thus, quantitative research adds numerical data to the more global theoretical findings.

Considering the objectives specified for the present study, the choice of a qualitative methodology appears optimal. COVID-19 as a global disruptive factor is a recent phenomenon per se, meaning that the timespan has been insufficient for a thorough examination of its profound impact. Moreover, as established within the previous sections, most studies related to the pandemic’s impact on global community within this limited time reflect the medical perspective on the subject matter. Research beyond the effect of COVID-19 on human health and healthcare systems usually revolves around the global economic trends without an emphasis on retail, especially in relation to smart cities. In light of the observed research gap, it is possible to conclude that the subject matter is underrepresented within the contemporary body of knowledge. As such, the situation requires a qualitative approach, which would provide a solid theoretical foundation for the subsequent investigation of the subject. This way, a relevant theoretical framework of reference will be established, ensuring a more in-depth understanding of the subject matter.

Within the qualitative framework, it appears optimal to concentrate on the investigation of relevant case studies for several reasons. The first crucial idea to be considered is that the existing research presupposes a detailed review of a specific unit, and the case study method is the perfect instrument for the investigator (Thomas, 2021). The hypothesis under consideration will be tested from various perspectives to verify the data and incorporate direct observations from policies and other legal documents into the current research. The existing research project is an attempt to go beyond a casual data collection process and focus on how the definitive outcomes in the three cities under review could be achieved. All policy-related information serves as a critical component of the research project that can be utilized to verify certain ideas or consider solutions that have not been addressed when coping with the Covid-19 pandemic on the city level (Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2021). With a detailed case study, the researcher could immediately verify their hypotheses and promote possible improvements that stem from the available data.

Another crucial consideration that makes the case study method the perfect choice for the current research project is that no detailed sampling procedures have to be implemented to collect the data. The three cities and their policymaking decisions will be reviewed from the perspective of social units in order to see how the short- and long-term effects of the pandemic could affect various locations. Hence, the researcher will have a chance to assess all the factual data and make conclusions based on varied considerations and detailed descriptions of policies relevant to the cities under review. The case study method will directly support the researcher’s hypothesis because outside observation is going to be used to analyze specific incidents and decisions related to the topic of the study (Hancock & Algozzine, 2017). Without detailed information on the incidents and their outcomes, the researcher would not be able to generalize certain ideas or behaviors characteristic of smart cities and their management. The three case studies represent an opportunity to see the bigger picture and predict future trends in the field of incident responses.

The next rationale for the case study method revolves around the idea that it provides the researcher with an opportunity to perform continuous analysis of factual data and reach informed verdicts. As a series of case studies on smart city initiatives in New York, Dubai, and Singapore, the current research provides a detailed outlook on how additional data could be collected to improve the existing state of affairs. According to Thomas (2021), the case study method serves as a means of an unremitting examination of data because it adds validity to the available data over time and not instantly. Despite the unpredictable overall amount of data that could be collected by the researcher, the case study method represents one of the best means of validating a hypothesis because it is multi-layered. Even though it could provoke slight inefficiencies in the process of data collection, the quality of the evidence would not be reduced.

One more factor to consider when picking the case study method was that the latter could be a great opportunity to compare data sets. Knowing that there are three smart cities under scrutiny, it would become an essential task for the researcher to build on individual observations and policy outcomes to test hypotheses and attain research objectives. Since smart cities could respond differently to identical stimuli, it would be an essential task to analyze all the related documents and see how smart cities could be controlled via policing. Every related document could become a research component required to analyze individual outcomes and forecast the future of smart cities after direct exposure to the Covid-19 pandemic. With the case study method, the idea should be to take all the information from various demographics and turn it into a vivid comparison of available evidence (Thomas, 2021). Overall, this helped the researcher to go beyond testing hypotheses and create room for proposals aimed at the disruption of existing technologies and smart city frameworks.

The ultimate reason to implement the case study method was the fact that it could help the researcher increase their knowledge and generalize all the available data. The existing analytical tools could significantly facilitate the process of data collection and analysis since document scrutiny represents an objective method of assessing the effectiveness of policies in place. In line with Hancock and Algozzine (2017), all the data obtained by means of case studies could be generalized to create a foundation for additional hypotheses that could be used by the researcher to re-test the initial premise and see how the data comparison supports it. Therefore, case studies on New York, Singapore, and Dubai uncovered the unique outcomes and unusual features of smart city initiatives. The outcomes of the pandemic are unpredictable, but the effect of smart city policing can be viewed through the prism of detailed case studies.

Data Collection

The present research aims to address the implementation of smart city technology in the retail sector in light of the COVID-19 pandemic’s onset and aftermath. During the initial stages of the study, a set of key verbal identifiers was determined, as well. The phrases “COVID-19 smart cities”, “pandemic in smart cities”, “smart city retail”, “COVID-19 retail smart cities”, and related equivalents were used in the search process. Such search phrases returned a sufficient number of relevant research materials, in which the authors discuss the impact of the coronavirus outbreak on lives in cities traditionally viewed as smart. As for the exact selection criteria, it was nearly impossible to categorize the findings based on the time factor. Evidently, COVID-19 is a new phenomenon, and the most relevant studies appeared in 2020. As of today, the Global Smart City Index comprises 109 entries (IMD, 2021). Each agglomeration within this list demonstrates an array of differences that account for the increased diversity of the Index.

At the same time, the core of the references was expected to be published in English, thus representing the international body of knowledge. The studies were to be published in respected, peer-reviewed journals. Finally, once the selection procedure was completed and returned ten sources, the findings were examined and synthesized based on specific categories. In order to showcase the global varieties of the response, the research relied on the examples of three smart cities. Considering the location of the study, the city of Dubai became the first choice of a smart city. Next, informed by the 2020 IMD Business School’s Index of Smart Cities, the researcher selected the cities of Singapore and New York, occupying the 1st and the 10th places of the index, respectively (IMD, 2021). This selection should illustrate the diversity of the smart models of retail in

Sampling and Justification

Following the initial review of the literature presented in Chapter 2, the research continued to analyze the specific cases of retail industry in Dubai, New York, and Singapore. The total of 30 relevant studies have been selected for the examination with the purpose of discerning and documenting the key features of the pandemic response in each smart city. The specified sample appears adequate in light of the research objectives, as well as the overall novelty of the problem. This number implies a review of 10 article per each smart territory selected, which accounts for the diversity and objectivity of the expert opinions. The investigation and comparison of such findings allowed the author of the dissertation to examine the prevalence of specific response models in retail. In turn, these findings proved instrumental for the development of a uniform response framework that addresses the aftermath of global pandemic in smart cities.

Dubai is the first area of interest that has been selected for the purposes of the present study. According to the article by Haak-Saheem (2020), the secret to Dubai’s success lies in its ability to attract foreign direct investments while developing its international talent pool. In the age of COVID-19, these objectives became more difficult to attain. More specifically, the pandemic had a strong impact on international connections, virtually paralyzing global travel, and Dubai’s industries, including retail, largely depend on international talents. In response to the emerging challenges, local policy-makers resorted to smart city opportunities. For example, the year 2020 saw the creation of Dubai’s Virtual Labor Market that helped expatriates remain employed in this difficult time (Haak-Saheem, 2020). This initiative is central to the article, and it serves to highlight the ability of Dubai to adjust to new circumstances through the prism of smart city technology.

Singapore remains one of the leading smart cities in the world, which justifies its inclusion in the research framework. In fact, the 2020 IMD Business School’s Index of Smart Cities put it in the1st place (IMD, 2021). In their article, Costa and Peixoto (2020) review a range of smart urban territories, but Singapore holds a place of special significance within the research. According to the authors, such smart cities possess strong tools, which help mitigate the impact of the pandemic while helping people live as normally as possible. Costa and Peixoto (2020) trace Singapore’s technological resilience to the 2003 SARS outbreak, after which the city made major improvements in its smart infrastructure. As of now, Singapore boasts its Smart Nation program, which aims to increase the perceived quality of people’s lives through technology. Such products enable access to a wide variety of services via the Internet, which is both safe and convenient for people. Such measures reflect Moreover, the popularity of Smart Nation allows local authorities to use the affiliated apps to keep records of people in contact with COVID-19.

The third point of interest is represented by the city of New York, which is a worldwide brand on its own. Being the economic center of the United States, this city has the image of one of the most advanced territories, which makes it worthy of investigation in regard to the subject matter. Costa and Peixoto (2020) review this city among other smart agglomerations of the world in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. The article states that most of New York’s smart city policies aimed directly at the sphere of healthcare. For example, the New York eHealth Collaborative (NYeC) organization has established a statewide framework for rapid information exchange between healthcare facilities. Similar programs facilitate medical teams’ access to their patients’ records from other institutions in order to improve the quality of the direct response to COVID-19. However, while the emphasis on healthcare capacity is natural and indispensable, the city could benefit from a more profound implementation of smart technology in other spheres. Specifically, the smart response of retail is underrepresented, in spite of the city’s status, which justifies New York’s inclusion in the project.

Data Analysis

Considering the format of the study, the analysis of the data is conducted using the qualitative model of research. The first stage is reserved for the narrative analysis of the obtained findings. It consists of the text source examination and documentation with the aim of extracting the crucial elements of each piece of writing. Following the initial documentation of the sources, their contents are analyzed in terms of the key themes and terms that describe the retail industry’s response to the pandemic. Accordingly, the second phase is represented by the thematic analysis of the data, during which the extracted information will be placed in the corresponding categories. More specifically, this stage will provide a classification of the response measures in the area of smart city retail. For example, certain paradigms are centered on the preservation of sales levels and businesses’ profits, whereas other are pointed at the customer convenience and safety.

The findings of the thematic analysis are then processed through the theoretical framework synthesized during the initial review of the literature. The aim of this stage is to determine whether the practical measures of smart city retail in the age of COVID-19 correspond with the general perception of the smart crisis response. In other words, the idea is to determine whether the existing paradigms of response in smart cities suffice for the effective mitigation of the pandemic’s impact on retail. Based on these findings, the final evaluation is produced, resulting in a practice-oriented, evidence-based guiding framework for the effective crisis response in smart cities’ retail sectors.

Ethical Considerations and Limitations of the Study

The present study is conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of academic research. The lack of engagement of individual participants facilitates this process, as the research procedures are centered on the analysis of the published academic sources. In order to prevent the infringement of academic integrity, each source is properly documented in terms of both in-text references and the overall reference list. All ideas and facts that originate in third party’s research are documented and attributed to the original authors. At the same time, the absence of an author attribution indicates that the presented data is a new addition, developed or synthesized in the course of the present research.

In light of the project’s methodology, it is possible to outline the primary limitations that are associated with it. First of all, while the qualitative model of the study accounts for the better understanding of the subject matter, it does not provide measurable indicators that would reflect the efficiency of specific frameworks. As such, further quantitative studies are required within the framework that is developed in the course of the present research. In addition, the sample of the project is limited to three representatives of the global Smart City Index. This list comprises 106 other entries, which may demonstrate varying results under the same conditions. In this regard, additional studies of other smart areas may instill further alterations of the provided response paradigm. Overall, the presented research marks the starting point of investigating the retail industry’s response in smart cities during COVID-19. The body of knowledge will benefit from subsequent research that would elaborate on the obtained findings.

Results and Discussions

The thematic assessment detected ten significant assistances of smart resolution technological innovations to the four resilience capabilities, comprising adaptation, absorption, planning, and recovery.

Planning and Preparation

Centred on our creation of the literature, smart city and smart technologies policies have played a significant role or are projected to contribute to improved planning and preparation through among other things, preparing and providing smart city infrastructure, facilitating collaborative and integrated planning and management, and using smart technologies for forecasting and prediction and for identifying hotspots that can contribute to prevent or minimize disease outbreak. Some of these actions should be done before the pandemic, whereas some others could have an ongoing and emergent nature and facilitate enhanced urban planning and management during different stages/waves of the pandemic.

Preparing and Offering Smart City Infrastructure

Planning and preparatory activities and measures taken before the occurrence of adverse events may affect the abilities to respond and recover. Although there have always been concerns about disease outbreaks that could become global health threats, the outbreak of COVID-19 surprised many cities around the world because of limited pre-event preparations [26]. However, there have also been some cities that have done better preparations, leading to a relatively better response. In fact, some cities that have Sustainability 2021, 13, 8018 7 of 28 retail businesses have suffered the least are those that have reacted in a timely and intelligent manner, based on lessons learned from previous disease outbreaks such as SARS. Among other things, those previous experiences have led to increased investment in smart city infrastructures. In addition, investment in smart technologies could have been driven by other factors such as national smart city development policies or the hosting of major sporting or other events. During this recent pandemic, such cities have repurposed some of their existing smart city infrastructure to facilitate improved response abilities. For instance, in some cases, cities through their retail chains have repurposed the retail of athletes’ wearable devices for new purposes, such as remote health monitoring and modeling the virus’s spread.

Singapore and New York are examples of relatively well-prepared smart cities that have been relatively successful in controlling the impacts of the pandemic on their retail industry. New York was one of the main cities that was hit by SARS in 2003, and its retail sector was psychologically and practically prepared to encounter COVID-19. Various scholars believe that New York’s success in containing the virus can be attributed to two measures that are entrenched in the city’s planning and grounding exertions. First, the timely enactment of boundary control and the shutting of land precincts within seven days after observing the first positive case. Second, using smart machineries to cultivate an operative testing structure and locating affected businesses. Another successful event, Singapore, which is a city that made substantial investments in technological advancement to prepare for the 2016 Summer Olympics. Urban control and command centers developed during the Olympics for security purposes were reproposed during the pandemic to facilitate surveillance and tracing and tracking of infected individuals. It also allowed real-time monitoring of the changing urban dynamics and designing appropriate measures in response to the changing conditions to ensure a timely return to normal conditions. Similarly, out of the 100 smart cities that are part of India’s smart city program, 45 have repurposed their integrated command and control centers as COVID-19 war rooms.

One specific technology that has been highlighted for its contribution to pandemic control is 5G. Indeed, it has played a very important role in fighting the pandemic in cities that it operates in, such as Jamaica Queens and Singapore. While 5G infrastructure is more costly and complicated than 4G and 3G, it improves the efficiency, speed, and flexibility of the pandemic-related interventions such as telemedicine, supply chain management, self-isolation, and contact monitoring, and it allows rapid implementation of health service. However, the existence of smart infrastructure may not always translate into a better response to the pandemic, and it should be coupled with other factors such as the availability of emergency plans and the agility of authorities. For instance, scholars emphasize that the data advantage that smart cities have compared to the other cities may not always help them to cope with the virus when, like other cities, they are not well prepared for a prevailing virus such as COVID-19. In contrast, cities that are not considered “smart” but that have emergency plans and know how to implement them effectively may be able to adapt quickly and show agility in delivering services in other innovative ways. These cities often have open, transparent, and accountable leadership and build partnerships with various public, private, and civil society stakeholders [35]. Despite this, smart infrastructures have shown great potential to facilitate an improved response and, as discussed below, they can also facilitate integrated approaches that further strengthen partnerships and collaboration. 4.1.2. Facilitating Collaborative and Integrated Planning and Management Cooperation between different sectors is essential for a timely response and recovery, as shown in places such as China, South Korea, and Singapore. Smart solutions can facilitate such cooperation for instance, the establishment of a multi-department information monitoring and sharing platform in Shanghai has facilitated cooperation between different departments, hospitals, and institutions, contributing to integrated management. In contrast, evidence shows that fragmented governance and limited cooperation between Sustainability 2021, 13, 8018 8 of 28 different sectors and levels of governance has led to conflicts and made it difficult to combat the pandemic in some cities in the US and Australia. Obviously, fragmented management is a long-standing problem and is, arguably, still dominant in many cities and across different sectors. For instance, traditionally public health emergency management systems have been centralized and relied on epidemiology and biomedical sciences only. This centralized model has proved ineffective in responding to the recent pandemic. Instead, a new model wherein multidisciplinary knowledge/experience sharing can facilitate cooperative action, including urban authorities and other stakeholders, is needed. This will enable accessibility to data needed for evidence-based decision making and will allow coordinated, efficient, and more effective actions towards achieving common goals. Such a new model can enhance resilience and adaptive capacity. Successful cases of using smart technologies and platforms exist that can inspire a paradigm shift towards more integrated urban planning and management. As a case in point, around the world, urban observatories and similar platforms such as integrated command and control centers have proved very effective in facilitating evidence-based and integrated responses to the pandemic and also in enhancing trust across different stakeholders and urban sectors, which is essential for an effective response to the pandemic. In Johannesburg, South Africa, the Gauteng City-Region Observatory (GCRO) used its data visualization and analytics capacities to identify social and environmental risks. It has helped understanding risk factors related to, for example, access to food, hygiene, and healthcare that may become more complicated when compounded by the pandemic effects. This integrated impact assessment allows designing and implementing suitable policy interventions. In South Korea, an “Epidemic Investigation Support System” (EISS) system has been developed to facilitate integrated urban management in response to the pandemic through analysis of COVID-19 data. The EISS system has facilitated integrated and seamless communication between different institutions. Conventional communication methods are based on bureaucratic processes for data acquisition and exchange, requiring excessive human resources and resulting in delays. In contrast, the EISS system facilitates real-time inter-institutional communication and information exchange with due attention to security issues. Compared to the manual method, this will reduce the time needed for processing data and, since the database is fully encrypted, the effects of potential security incidents will be minimized [40]. Moreover, the fact that an urban observatory constantly collects data related to different urban parameters allows collecting baseline databases that can help understand the level of impacts in the aftermath of crises such as COVID-19. In addition, the readily available data of the urban observatories enables taking timely data-informed decisions and mobilizing resources for effective disaster response. In other contexts such as New Delhi and Newcastle, the coordination capacity of urban observatories and their utility for encouraging collaboration and facilitating paradigm shift from silo-based to integrated governance are demonstrated. To further enhance the robustness of urban observatories, they can be developed based on innovative technologies such as block chain. In fact, block chain technology allows setting up a secure and distributed network for collecting, storing, and sharing information on COVID-19 patients, urban operations, and other variables. This way, a distributed database can be developed that makes it possible for policy makers and healthcare authorities to use this accurate and trustable data source for designing necessary response measures. This can also facilitate developing early warning systems based on real-time data collection and analysis and can strengthen the forecasting and prediction capacities.

Conclusion

Summary of Main Argument

This research paper emphasizes on the importance of the retail industry in economic development of a society. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the retail sector was severely affected as it faces a sales drop of nearly 6% which translates to hundreds of billion dollars financial losses. The effects of the economic crises were evident globally as many operations became paralyzed. Some of the most affected sectors were schools, entertaining centers, the manufacturing, and transportation industry. The key to recover from these economic crises is the retail industries in the smart cities. A smart city is an urban area which uses modern technologies and expertise of the human capacity to provide real time response to the demand of the community. Since smart cities are designed to provide real time response to demands, they may be in a better place to provide solutions to the Covid-19 pandemic through technological advancement. Smart cities manufacture smart ideas which require a high degree of flexibility and adaptability.

The increase anxiety and uncertainty levels during the pandemic led to a change in consumer behavior. This led to the retail sector facing colossal impacts during and after the crisis. In reaction to the change in consumer behavior, most retailers shifted their operations to online platforms which were more favourable at the moment. The transition was accompanied by technological advancements from both the consumer and retailer’s end. This was a starting point in effort to mitigate against the impacts of Covid-19. This research paper focused on determining why New York, Dubai, and Singapore managed to utilize their potential and the instruments they deployed.

Significant attention was focused on the epidemiological properties of the virus while little was said about its economic impacts. This is a natural phenomenon as Covid-19 was a medical issue that needed emergency response. Numerous smart cities studies mainly focused on the medical perspective, for instance, health care centres and supply of medical equipment to address the challenge. The pandemic and the restrictions that followed affected the normal way of life and the global economic state. New policies were enacted by various governments to address the energies challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) regularly updated and advised authorities on the policies to implement to address the disease. The most common policies enacted were transport restrictions, closure of non-essential businesses and lockdowns. To adapt to the change, many organizations opted to hire a work from home system. In the retail sector, in smart cities more adaptive policies needed to be implemented by use of technology but the ways of do so remained unclear. Hence, there is need for more research on the issue to develop efficient policies on national and corporate authority levels.

This research paper focused on establishing how smart cities have dealt with the Covid-19 aftermath with a focus on New York, Dubai and Singapore. To help in further study into the topic, the paper aimed at answering a series of questions such as; what’s strategies smart cities used to deal with crisis; how smart cities used these strategies or others to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on retail industries; and to devise evidence-based guidelines for the smart city retail industry’s response to a pandemic scenario.

Validity and Reliability of the Findings and Arguments

When searching for relevant articles to analyze, the researcher used phrases such as “COVID-19 smart cities”, “pandemic in smart cities”, “smart city retail”, and “COVID-19 retail smart cities” to retrieve relevant articles. To avoid bias information, the researcher further filtered the search based on categories k with more specific phrases such as Smart city policy, economic impact Covid- 19, smart city retails. The researcher analyzed the abstract of the retrieved papers filtering the irrelevant ones. Further, the research filtered the references based on full text reading and reference scanning. This study this contains the most relevant articles since Covid-19 is a new issue globally. The researcher analyzed the most relevant articles thus providing valid and reliable information.

Results in the Context of the UAE

The present study selected Dubai as the first area of interest due to its ability to attract foreign direct investments and creating a great international pool of talents. The prevalence of Covid-19 had a significant impact of the international relations in the city due to paralyzed global travel. Since Dubai’s industry, especially the retail industries, depend on international connections, travel limitations paralyzed their operations. To respond to the emerging challenges, local policy makers resorted to smart city opportunities. An example of these opportunities is the creation of the Dubai’s Virtual Labour Market that assisted expatriates remain employed during the challenging time. Dubai responded to the challenges through prism of smart city technology.

Recommendations

Without a doubt, Smart cities respond in real time to the demands and challenges by use of technological advancements. However, the smart cities only respond to challenges faced within it. Most of the time, smart cities do not generate solutions that affect the underdeveloped areas. Hence, there is a gap in recognizing the need of a region, a country or global challenges. Smart cities should be designed to provide real time response to global challenges to avoid adverse effects in case of a crisis.

Implications of the study

Globally, Covid-19 has impacted people’s lives and economies. The pandemic exposed the global unpreparedness in facing emergencies in various sectors. The health and financial sectors were most affected by the crisis. The retail industry sector has faced a significant financial loss. Extensive researcher is needed for the establishment of policies that will help the world respond to such emergencies without significantly affecting the livelihoods and economies. This study shows the efficiency of smart cities in responding to emergencies and reveals the various interventions implemented in the process. There is an urgent need in technology advancements and policies by governments and various economic sectors. There is need for more academic research to understand Covid-19 and its socio- economic ramifications on the society.

Reflection on Writing the Dissertation

Writing the dissertation was a rather challenging but existing experience for me. The first challenge was in choosing the most appropriate topic to discuss. However, being an economist with a liking for technology, I did not have a long search. I identify the challenge that is currently affecting businesses especially in the retail sector and settled on my current topic. Collecting the materials needed for the research was a very engaging experience as I had to get the most relevant articles to analyze. I took a considerable amount of time filtering through a series of articles until I settled on the 10 most relevant articles. The data analysis process was not very challenging since I had gathered all the data needed for the study. Moreover, writing the results section was only transferring the already acquired information from the analysis section to the results section. In the discussion, I gathered facts from different materials and related them to my findings to develop a good research and conclusions. I gained good research and writing skills from this process which I will utilize in conducting further research works.

Reference List

Ahad, M. A., Paiva, S., Tripathi, G., & Feroz, N. (2020). Enabling technologies and sustainable smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 61, 102301.

Allam, Z., & Jones, D. S. (2020). On the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and the smart city network: universal data sharing standards coupled with artificial intelligence (AI) to benefit urban health monitoring and management. Healthcare, 8, 1–9.

Aspers, P., & Corte, U. (2019). What is Qualitative in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology, 42, 139-160.

Bhatti, A. (2020). E-commerce trends during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Future Generation Communication and Networking, 13(2), pp. 1449-1452.

Caragliu, A., & Del Bo, C. F. (2018). Smart innovative cities: The impact of Smart City policies on urban innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 142, 373-383.

Costa, D. G., & Peixoto, J. P. J. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: A review of smart cities initiatives to face new outbreaks. Smart Cities, 2(2), 64–73.

D’Hauwers, R., Borghys, K., Vannieuwenhuyze, J.T.A., Walravens, N., & Lievens, B. (2020). Challenges in data-driven policymaking: Using smart city data to support local retail policies. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 6, 55-61.

Dannenber, P., Fuchs, M., Riedler, T., & Wiedemann, C. (2020). Digital transition by COVID-19 pandemic? The German food online retail. Journal of Economic and Human Geography, 111(3), 543-560.

De Nicola, A., Melchiori, M., & Villani, M. L. (2019). Creative design of emergency management scenarios driven by semantics: An application to smart cities. Information Systems, 81, 21-48.

Del Carmen Olmos-Gómez, M. (2020) ‘Validation of the smart city as a sustainable development knowledge tool: The challenge of using technologies in education during COVID-19’, Sustainability, 12(20).

Ghorbanzadeh, M., Kim, K., Ozguven, E. E., & Horner, M. W. (2021). Spatial accessibility assessment of COVID-19 patients to healthcare facilities: A case study of Florida. Travel Behavior and Society, 24, 95-101.

Goddard, E. (2020). The impact of COVID‐19 on food retail and food service in Canada: Preliminary assessment. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 6.

Gupta, M., Abdelsalam, M., & Mittal, S. (2020). Enabling and enforcing social distancing measures using smart city and its infrastructures: A COVID-19 use case.

Guven, H., Ayvaz Guven, E. T., & Akkaya, B. (2020). The status of the retail sector during and after the COVID-19 outbreak: What should strategic managers do? In B. Akkaya et al. (Eds.). Emerging trends and strategies for Industry 4.0: During and beyond COVID-19 (pp. 47-58). Sciendo.

Haak-Saheem, W. (2020). Talent management in Covid-19 crisis: How Dubai manages and sustains its global talent pool. Asian Business & Management, 19, 298–301.

Hancock, D. R., & Algozzine, B. (2017). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers. Teachers College Press.

IMD. (2021). Smart City Index 2020.

Inn, T. L. (2020). Smart city technologies take on COVID-19.

Ismagilova, E., Hughes, L., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Raman, K. R. (2019). Smart cities: Advances in research—An information systems perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 88-100.

Lai, C. S. et al. (2020). A review of technical standards for smart cities. Sustainable Clean Technologies, 2(3), 290-310.

Loske, D. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics: An empirical analysis in German food retail logistics. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 6.

Nanda, A., Xu, Y., & Zhang, F. (2021). How would the COVID-19 pandemic reshape retail real estate and high streets through acceleration of E-commerce and digitalization? Journal of Urban Management, 10(2), 110-124.

Pati, D., & Lorusso, L. N. (2018). How to write a systematic review of the literature. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 11(1), 15-30. Web.

Queirós, A., Faria, D., & Almeida, F. (2017). Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. European Journal of Education Studies, 3(9).

Sharifi, A., Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R., & Kummitha, R. K. R. (2021). Contributions of smart city solutions and technologies to resilience against the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. Sustainability, 13(14), 8018.

Silva, B. N., Khan, M., & Han, K. (2018). Towards sustainable smart cities: A review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 38, 697-713.

Smigiel, C. (2018). Urban political strategies in times of crisis: A multiscalar perspective on smart cities in Italy. European Urban and Regional Studies, 26(4), 336-348.

Sonn, J. W., Kang, M., & Choi, Y. (2020). Smart city technologies for pandemic control without lockdown. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 24(2), 149–151.

Soyata, T., Habibzadech, H., Ekenna, C., & Lozano, J. (2019). Smart city in crisis: technology and policy concerns. Sustainable Cities and Society, 50, 1-15.

Statista Research Department. (2021a). Retail market worldwide – Statistics & facts. Statista.

Statista Research Department. (2021b). Forecast for retail sales growth worldwide from 2018 to 2022. Statista.

Statista Research Department. (2021c,). Total retail sales worldwide from 2018 to 2022. Statista.

Thomas, G. (2021). How to do your case study. Sage.

Umair, M., Cheema, M. A., Cheema, O., Li, H., & Lu, H. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on IoT adoption in healthcare, smart homes, smart buildings, smart cities, transportation and industrial IoT. Sensors, 21(11), 3838.

Wojcik, D., & Ioannou, S. (2020). COVID‐19 and finance: Market developments so far and potential impacts on the financial sector and centres. Journal of Economic and Human Geography, 111(3), 387-400.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Coronavirus.

Yigitcanlar, T., Kamruzzaman, M., Foth, M., Sabatini-Marques, J., da Costa, E., & Ioppolo, G. (2019). Can cities become smart without being sustainable? A systematic review of the literature. Sustainable Cities and Society, 45(1), 348-365.