Abstract

The paper examines the effect of stress and anxiety on an individual’s mental performance. The research utilizes a reverse Stroop experiment to evaluate the mental performance of individuals when subjected to either up-regulation or down-regulation. In this experiment, the control group and the experimental group are subjected to similar conditions. The groups are subjected to high pressure, low pressure, and different threat levels. The paper employs the repeated measures study design where the sample is collected randomly from the university. The data collected from the experiment is merged, and statistical analysis is done on the data. The data has four dependent variables: performance, cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and threat appraisal. The research study uses mixed-method Anova, and the statistical significance of tests such Shapiro Wilk test and Bonferroni analysis are performed. From the results of the analysis, it is noted that there is a significant improvement in the post hoc tests, which implies that the exercise during the tests has a substantial improvement in the cognitive performance of individuals.

Introduction

Various researches have demonstrated that exercise is essential to cognitive performance (Harwood et al., 2019). Researchers use different tests to assess the performance of the brain in various activities. Stroop experiment measures the functionality of the cognizance and is mainly considered (Takahashi & Grove, 2020). The reverse Stroop task is a type of Stroop test that assesses inhibitory functions. Individuals are asked to relate to the word while disregarding the text color instead of recognizing the color and ignoring the word (Lautenbach et al., 2016). Even though the reverse-Stroop test is believed to measure Stroop task and inhibitory function, there are results in which the brain regions related to the Stroop task vary with those of the reverse-Stroop task (Scarpina & Tagini, 2017).

Researchers have used the reverse-Stroop test to investigate how acute exercise influences perform function (Tsukamoto et al., 2016). Large effect sizes have been obtained by these studies suggesting that the reverse-Stroop task is sensitive to the exercise effect. There is still a debate around the method measurement, although the Stroop and reverse-Stroop are adopted to evaluate the inhibitory function (Scarpina & Tagini, 2017)

Anxiety is a problem that most athletes face when they return to training after long-term or short-term injury to competing in various games (McLoughlin et al., 2021). The response to anxiety and stress is prevalent in the field of exercise and sports (Meijen et al., 2020). Several researchers define stress as transactional, implying that it is formed from the relationship between the environment and a performer (Cupples et al., 2021). The transactional stress theory is a dynamic process that is centralized on the cognitive and mental appraisal and the following coping responses (Didymus & Fletcher, 2017). The cognitive assessment focuses on the evaluation of the external and internal stimuli and their significance on individuals (Nicholls et al., 2016). Furthermore, it evaluates the relevant stressors. Whenever a conflict arises, an individual will determine whether the required resources are available and efficient to cope with the stressor (Lautenbach et al., 2016).

There is a distinction between the primary appraisal and the secondary appraisal as reviewed by various researches (Nicholls et al., 2016). The primary appraisal is the evaluation done following the commitments to goals, values, and beliefs of an individual and the world (Cumming et al., 2017). The primary appraisal ascribes to the meaning and importance of a situation (Hayward et al., 2017). The primary appraisal is divided into three: stressful appraisal, which leads to a considerable threat to the well-being of individuals, irrelevant appraisal, which has no harm to an individual; and benign-positive appraisal, which evaluates the likely stressors developing in the environment (Arnold et al., 2018). This research aims to compare the effects of up vs. down-regulation breathing on challenge/ threat appraisal, anxiety, and shooting task performance in low- and high-pressure conditions (Didymus & Fletcher, 2017). The null hypotheses are that the treatment effects are the same across all the variables and that there is no interaction effect. The alternative hypotheses are there is at least one different treatment, and there is an interaction effect.

Study Design

The research was conducted after the psychology review board approved it on June 1st, 2021. The study utilized the repeated measure so that every participant is exposed to all the research conditions. The method is selected because, if necessary, the experiment can be repeated. The advantage of this method is that the number of people required to conduct an experiment is less, and they are exposed to every experimental condition of the research study. The disadvantage of the method is that the order of events in the experiment tends to impact the participants’ behavior. The first within-subject factor is the experimental conditions, low pressure, and high pressure. The second within factor is the test-phase which consists of pre-test and the post-test. The between-subject factor is the intervention which consists of up-regulation and low-regulation. The dependent variables in the study are performance, cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and challenge/threat appraisal.

Participants

The experiment was conducted at Stamford university, and there were 16 males and 15 females from a sample size of 31. The participants’ age ranged from 18 to 40, and the education range was between undergraduate and postgraduate. The participants were from different racial backgrounds. They were provided with the consent form as a requirement for participation in the research study. The participants were given a choice of whether to continue with the research study or not. The participants were subjected to the control and experimental variable of the study.

Measures

Performance

The mean performance is measured from the participant’s outcome after being subjected to the two treatments, i.e., the up-regulation and the down-regulation, in different pressure levels and times.

Cognitive Anxiety

The variable is measured from the outcome of the participant before the intervention and after the intervention. It is determined from the pressure variations and the different time periods.

Somatic Anxiety

The variable is measured from the outcome of the participants in both interventions. It is determined from the pressure variations and the different time periods.

Challenge/Threat Appraisal

It is determined from participants’ outcome level of threat. It is determined from the interventions different pressure levels and different time periods.

Intervention Conditions

Upregulation

The up-regulation intervention in the study consisted of high breathing, which increases the number of receptors.

Down-regulation

The down-regulation intervention in the study consisted of low breathing, which reduces the number of receptors.

Procedure

The participants were given the consent paper and were assured that the data collected is confidential. Anyone who is not willing to continue with the research study can drop out of the study whenever they feel like it. Each participant was tested individually, and they were presented with words at the screen center surrounded by different color targets. In the first step, they were required to shoot on the target which matches the word displayed. The individuals were informed that the target disappears after 2 seconds after a series of shooting various targets. The second step involved shooting the target that matches the written color on the screen and the performance recorded. In the third step, they were allowed to breath and repeat the same steps as previous. The fourth step involves competing with other participants where they are supposed to shoot the target, and when they miss shooting, classmates will shoot them in the head. In the last step, they breath and then repeat the process.

Data Analysis

The data screening steps are typing data, whether discrete or continuous, checking the missing data, checking the normality of every variable used in the study, and checking whether the data has outliers. The primary analysis tests are the Shapiro Wilk test and the Three D’Agostino’s normality test. The between-subject factors subjected to this analysis are up-regulation and down-regulation, and the within factors are low-pressure, high-pressure, pre-test, and post-test. If there are any effects from the primary analysis, test for spherity using Mauchly’s test for spherity.

Results

Data Screening

The Shapiro-Wilk test for normal distribution shows all the variables exhibit a normal distribution except for the threat appraisal, wherein all the conditions do not assume a normal distribution. i.e., the p-value is less than 0.05.

Table 1.0: Normality tests

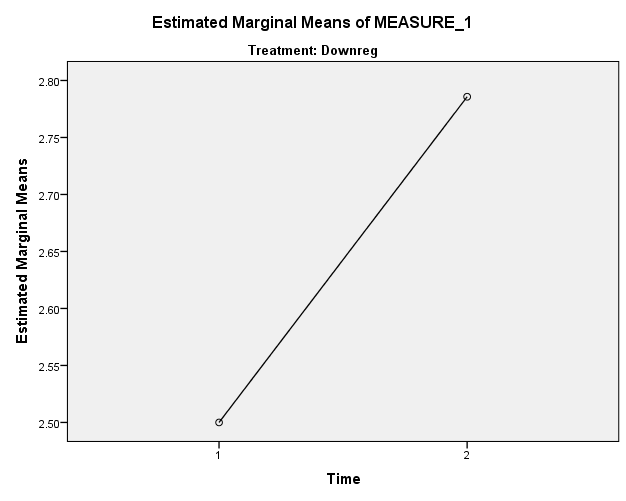

Table 2.0: Test of within Subjects in Downreg for cognitive anxiety under low pressure in post and pre-test

Table 3.0 Test between subjects in down reg for cognity anxiety under low pressure in post and pre test

The repeated measure results for threat appraisal shows that at low pressure p=0.01. The main effect between the intervention and the groups is significant with p =0.01. For cognitive anxiety, No main effect between groups for intervention (p = 0.365) at down-regulation. With interaction between intervention test phase (p <0.05). In Up-regulation, there is a main effect between groups for intervention (p = 0.04), with the interaction between intervention test phase (p <0.05), somatic anxiety has no effect between intervention groups at down-regulation (p = 0.909). With interaction between intervention test phase (p <0.05). For performance, no main effect between groups for intervention (p = 0.035) at down-regulation. No main effect between groups for intervention (p = 0.555) at up-regulation. For threat appraisal at high-pressure p <0.005. The main effect between the intervention and the groups with a p =0.01. For cognitive anxiety at high-pressure, P = main effect between groups for intervention (p = 0.365) at down-regulation. With interaction between intervention test phase (p <0.05). For somatic anxiety at high pressure, No main effect between groups for intervention (p = 0.909) at down-regulation. With interaction between intervention test phase (p <0.05). For performance, no main effect between groups for intervention (p = 0.133) at down-regulation.

Discussion

From the post hoc analysis results, shooting the target enhanced with the up-regulation group, which displays that the acute exercises such as sports are influenced by the mode of exercise of the sportsperson. The results show that exercising improves individuals’ mental performance, making them respond quickly to the stimuli. The random effects were very large in the research study, which yielded a correlation throughout the research experiment. From the results of Mixed Anova, we reject the null hypothesis that the treatment effects are the same because all the factor’s p values are significantly greater than 0.05. However, threat appraisal in all the pre-test and post-test analysis maintains its significance. This portrays that the threat analysis was not impacted by the individual exercise. The up and down-regulation has a significant role in the performance of the individual concerning cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and mean performance. The individuals exposed to up-regulation in both the high- and low-pressure conditions performed better in terms of performance mean, threat appraisal, cognitive anxiety, and somatic anxiety.

From the research conducted by Tsukamoto et al. (2016), acute exercises are essential to enhance reverse interference. Cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety are prevalent at the beginning of the experiment. After the intervention, the individuals’ stress reduces, and they begin coping with the sports environment (Arnold et al., 2016). However, the frequency of coping with exercise varies from one to another (Poulus et al., 2020).

References

Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Daniels, K. (2016). Organisational stressors, coping, and outcomes in competitive sport. Journal Of Sports Sciences, 35(7), 694-703. Web.

Aylward, J., & Robinson, O. (2017). Towards an emotional ‘stress test’: a reliable, non-subjective cognitive measure of anxious responding. Scientific Reports, 7(1). Web.

Brimmell, J., Parker, J., Wilson, M., Vine, S., & Moore, L. (2019). Challenge and threat states, performance, and attentional control during a pressurized soccer penalty task. Sport, Exercise, And Performance Psychology, 8(1), 63-79. Web.

Brosschot, J., Verkuil, B., & Thayer, J. (2016). The default response to uncertainty and the importance of perceived safety in anxiety and stress: An evolution-theoretical perspective. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders, 41, 22-34. Web.

Brown, D., & Fletcher, D. (2016). Effects of Psychological and Psychosocial Interventions on Sport Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(1), 77-99. Web.

Chadha, N., Turner, M., & Slater, M. (2019). Investigating Irrational Beliefs, Cognitive Appraisals, Challenge and Threat, and Affective States in Golfers Approaching Competitive Situations. Frontiers In Psychology, 10. Web.

Chennaoui, M., Bougard, C., Drogou, C., Langrume, C., Miller, C., Gomez-Merino, D., & Vergnoux, F. (2016). Stress Biomarkers, Mood States, and Sleep during a Major Competition: “Success” and “Failure” Athlete’s Profile of High-Level Swimmers. Frontiers In Physiology, 7. Web.

Cumming, S., Turner, M., & Jones, M. (2017). Longitudinal Changes in Elite Rowers’ Challenge and Threat Appraisals of Pressure Situations: A Season-Long Observational Study. The Sport Psychologist, 31(3), 217-226. Web.

Cupples, B., O’Connor, D., & Cobley, S. (2021). Facilitating transition into a high-performance environment: The effect of a stressor-coping intervention program on elite youth rugby league players. Psychology Of Sport and Exercise, 56, 101973. Web.

Didymus, F., & Fletcher, D. (2017). Organizational stress in high-level field hockey: Examining transactional pathways between stressors, appraisals, coping and performance satisfaction. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(2), 252-263. Web.

Dierolf, A., Schoofs, D., Hessas, E., Falkenstein, M., Otto, T., & Paul, M. et al. (2018). Good to be stressed? Improved response inhibition and error processing after acute stress in young and older men. Neuropsychologia, 119, 434-447. Web.

Dixon, J., Jones, M., & Turner, M. (2019). The benefits of a challenge approach on match day: Investigating cardiovascular reactivity in professional academy soccer players. European Journal of Sport Science, 20(3), 375-385. Web.

Dixon, M., Turner, M., & Gillman, J. (2016). Examining the relationships between challenge and threat cognitive appraisals and coaching behaviours in football coaches. Journal Of Sports Sciences, 35(24), 2446-2452. Web.

Do, B., Mason, T., Yi, L., Yang, C., & Dunton, G. (2021). Momentary associations between stress and physical activity among children using ecological momentary assessment. Psychology Of Sport and Exercise, 55, 101935. Web.

Fortes, L., Nascimento-Júnior, J., Mortatti, A., Lima-Júnior, D., & Ferreira, M. (2018). Effect of Dehydration on Passing Decision Making in Soccer Athletes. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 89(3), 332-339. Web.

Foskett, R., & Longstaff, F. (2018). The mental health of elite athletes in the United Kingdom. Journal Of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(8), 765-770. Web.

Gagnon, S., Waskom, M., Brown, T., & Wagner, A. (2018). Stress Impairs Episodic Retrieval by Disrupting Hippocampal and Cortical Mechanisms of Remembering. Cerebral Cortex, 29(7), 2947-2964. Web.

Gantois, P., Caputo Ferreira, M., Lima-Junior, D., Nakamura, F., Batista, G., Fonseca, F., & Fortes, L. (2019). Effects of mental fatigue on passing decision-making performance in professional soccer athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 20(4), 534-543. Web.

Hamlin, M., Wilkes, D., Elliot, C., Lizamore, C., & Kathiravel, Y. (2019). Monitoring Training Loads and Perceived Stress in Young Elite University Athletes. Frontiers In Physiology, 10. Web.

Harwood, C., Thrower, S., Slater, M., Didymus, F., & Frearson, L. (2019). Advancing Our Understanding of Psychological Stress and Coping Among Parents in Organized Youth Sport. Frontiers In Psychology, 10. Web.

Hase, A., O’Brien, J., Moore, L., & Freeman, P. (2019). The relationship between challenge and threat states and performance: A systematic review. Sport, Exercise, And Performance Psychology, 8(2), 123-144. Web.

Hayward, F., Knight, C., & Mellalieu, S. (2017). A longitudinal examination of stressors, appraisals, and coping in youth swimming. Psychology Of Sport and Exercise, 29, 56-68. Web.

Hepler, T., & Andre, M. (2021). Decision Outcomes in Sport: Influence of Type and Level of Stress. Journal Of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 43(1), 28-40. Web.

Herman, J., McKlveen, J., Ghosal, S., Kopp, B., Wulsin, A., & Makinson, R. et al. (2016). Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Comprehensive Physiology, 603-621. Web.

Huber, M., Brown, A., & Sternad, D. (2016). Girls can play ball: Stereotype threat reduces variability in a motor skill. Acta Psychologica, 169, 79-87. Web.

Irwin, C., Campagnolo, N., Iudakhina, E., Cox, G., & Desbrow, B. (2017). Effects of acute exercise, dehydration and rehydration on cognitive function in well-trained athletes. Journal Of Sports Sciences, 36(3), 247-255. Web.

Isaksson, A., Martin, P., Kaufmehl, J., Heinrichs, M., Domes, G., & Rüsch, N. (2017). Social identity shapes stress appraisals in people with a history of depression. Psychiatry Research, 254, 12-17. Web.

Jones, H., Williams, E., Marchant, D., Sparks, S., Bridge, C., Midgley, A., & Mc Naughton, L. (2016). Improvements in Cycling Time Trial Performance Are Not Sustained Following the Acute Provision of Challenging and Deceptive Feedback. Frontiers In Physiology, 7. Web.

Khalili-Mahani, N., & De Schutter, B. (2019). Affective Game Planning for Health Applications: Quantitative Extension of Gerontoludic Design Based on the Appraisal Theory of Stress and Coping. JMIR Serious Games, 7(2), e13303. Web.

Kunrath, C., Nakamura, F., Roca, A., Tessitore, A., & Teoldo Da Costa, I. (2020). How does mental fatigue affect soccer performance during small-sided games? A cognitive, tactical and physical approach. Journal Of Sports Sciences, 38(15), 1818-1828. Web.

Laborde, S., Lentes, T., Hosang, T., Borges, U., Mosley, E., & Dosseville, F. (2019). Influence of Slow-Paced Breathing on Inhibition After Physical Exertion. Frontiers In Psychology, 10. Web.

Lautenbach, F., Laborde, S., Putman, P., Angelidis, A., & Raab, M. (2016). Attentional distraction by negative sports words in athletes under low- and high-pressure conditions: Evidence from the sport emotional Stroop task. Sport, Exercise, And Performance Psychology, 5(4), 296-307. Web.

Lopes Dos Santos, M., Uftring, M., Stahl, C., Lockie, R., Alvar, B., Mann, J., & Dawes, J. (2020). Stress in Academic and Athletic Performance in Collegiate Athletes: A Narrative Review of Sources and Monitoring Strategies. Frontiers In Sports and Active Living, 2. Web.

Madigan, D., Rumbold, J., Gerber, M., & Nicholls, A. (2020). Coping tendencies and changes in athlete burnout over time. Psychology Of Sport and Exercise, 48, 101666. Web.

Malterud, K., Siersma, V., & Guassora, A. (2016). Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753-1760. Web.

McLoughlin, E., Fletcher, D., Slavich, G., Arnold, R., & Moore, L. (2021). Cumulative lifetime stress exposure, depression, anxiety, and well-being in elite athletes: A mixed-method study. Psychology Of Sport and Exercise, 52, 101823. Web.

Meijen, C., Turner, M., Jones, M., Sheffield, D., & McCarthy, P. (2020). A Theory of Challenge and Threat States in Athletes: A Revised Conceptualization. Frontiers In Psychology, 11. Web.

Moore, L., Freeman, P., Hase, A., Solomon-Moore, E., & Arnold, R. (2019). How Consistent Are Challenge and Threat Evaluations? A Generalizability Analysis. Frontiers In Psychology, 10. Web.

Moore, L., Young, T., Freeman, P., & Sarkar, M. (2017). Adverse life events, cardiovascular responses, and sports performance under pressure. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(1), 340-347. Web.

Morriss, J., McSorley, E., & van Reekum, C. (2017). I don’t know where to look: the impact of intolerance of uncertainty on saccades towards non-predictive emotional face distractors. Cognition And Emotion, 32(5), 953-962. Web.

Mosley, E., Laborde, S., & Kavanagh, E. (2017). The contribution of coping related variables and cardiac vagal activity on the performance of a dart throwing task under pressure. Physiology & Behavior, 179, 116-125. Web.

Musculus, L. (2018). Do the best players “take-the-first”? Examining expertise differences in the option-generation and selection processes of young soccer players. Sport, Exercise, And Performance Psychology, 7(3), 271-283. Web.

Nicholls, A., Taylor, N., Carroll, S., & Perry, J. (2016). The Development of a New Sport-Specific Classification of Coping and a Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Different Coping Strategies and Moderators on Sporting Outcomes. Frontiers In Psychology, 7. Web.

Nowacki, J., Heekeren, H., Deuter, C., Joerißen, J., Schröder, A., Otte, C., & Wingenfeld, K. (2019). Decision making in response to physiological and combined physiological and psychosocial stress. Behavioral Neuroscience, 133(1), 59-67. Web.

Parker, P., Perry, R., Hamm, J., Chipperfield, J., Hladkyj, S., & Leboe-McGowan, L. (2018). Attribution-based motivation treatment efficacy in high-stress student athletes: A moderated-mediation analysis of cognitive, affective, and achievement processes. Psychology Of Sport and Exercise, 35, 189-197. Web.

Parkin, B., & Walsh, V. (2017). Gunslingers, poker players, and chickens 3: Decision making under mental performance pressure in junior elite athletes. Progress In Brain Research, 339-359.

Parkin, B., Warriner, K., & Walsh, V. (2017). Gunslingers, poker players, and chickens 1: Decision making under physical performance pressure in elite athletes. Progress In Brain Research, 291-316.

Poulus, D., Coulter, T., Trotter, M., & Polman, R. (2020). Stress and coping in Esports and the Influence of Mental Toughness. Frontiers In Psychology, 11. Web.

Randall, R., Nielsen, K., & Houdmont, J. (2018). Process Evaluation for Stressor Reduction Interventions in Sport. Journal Of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 47-64. Web.

Robazza, C., Izzicupo, P., D’Amico, M., Ghinassi, B., Crippa, M., & Di Cecco, V. et al. (2018). Psychophysiological responses of junior orienteers under competitive pressure. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0196273.

Rossato, C., Uphill, M., Swain, J., & Coleman, D. (2016). The development and preliminary validation of the Challenge and Threat in Sport (CAT-Sport) Scale. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(2), 164-177. Web.

Rumbold, J., Fletcher, D., & Daniels, K. (2018). Using a mixed method audit to inform organizational stress management interventions in sport. Psychology Of Sport and Exercise, 35, 27-38.

Sammy, N., Anstiss, P., Moore, L., Freeman, P., Wilson, M., & Vine, S. (2017). The effects of arousal reappraisal on stress responses, performance and attention. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(6), 619-629.

Scarpina, F., & Tagini, S. (2017). The Stroop Color and Word Test. Frontiers in Psychology, 8.

Schapschröer, M., Lemez, S., Baker, J., & Schorer, J. (2016). Physical Load Affects Perceptual-Cognitive Performance of Skilled Athletes: a Systematic Review. Sports Medicine – Open, 2(1).

Shields, G. (2017). Response: Commentary: The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: A meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Frontiers In Psychology, 8. Web.

Shields, G., Rivers, A., Ramey, M., Trainor, B., & Yonelinas, A. (2019). Mild acute stress improves response speed without impairing accuracy or interference control in two selective attention tasks: Implications for theories of stress and cognition. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 108, 78-86. Web.

Slavich, G., & Shields, G. (2018). Assessing Lifetime Stress Exposure Using the Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults (Adult STRAIN): An Overview and Initial Validation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80(1), 17-27.

Smith, M., Zeuwts, L., Lenoir, M., Hens, N., De Jong, L., & Coutts, A. (2016). Mental fatigue impairs soccer-specific decision-making skill. Journal Of Sports Sciences, 34(14), 1297-1304.

Smith, M., Zeuwts, L., Lenoir, M., Hens, N., De Jong, L., & Coutts, A. (2021). Mental fatigue impairs soccer-specific decision-making skill. Web.

Starcke, K., & Brand, M. (2016). Effects of stress on decisions under uncertainty: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 142(9), 909-933.

Stoker, M., Maynard, I., Butt, J., Hays, K., Lindsay, P., & Norenberg, D. (2017). The Effect of Manipulating Training Demands and Consequences on Experiences of Pressure in Elite Netball. Journal Of Applied Sport Psychology, 29(4), 434-448. Web.

Sturmbauer, S., Shields, G., Hetzel, E., Rohleder, N., & Slavich, G. (2019). The Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults (Adult STRAIN) in German: An overview and initial validation. PLOS ONE, 14(5), e0216419. Web.

Takahashi, S., & Grove, P. (2020). Use of Stroop Test for Sports Psychology Study: Cross-Over Design Research. Frontiers In Psychology, 11.

Tamminen, K., Sabiston, C., & Crocker, P. (2018). Perceived Esteem Support Predicts Competition Appraisals and Performance Satisfaction Among Varsity Athletes: A Test of Organizational Stressors as Moderators. Journal Of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 27-46.

Teoh, A., & Hilmert, C. (2018). Social support as a comfort or an encouragement: A systematic review on the contrasting effects of social support on cardiovascular reactivity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 23(4), 1040-1065.

Thornton, C., Sheffield, D., & Baird, A. (2019). Motor performance during experimental pain: The influence of exposure to contact sports. European Journal of Pain, 23(5), 1020-1030. Web.

Trotman, G., Williams, S., Quinton, M., & Veldhuijzen van Zanten, J. (2018). Challenge and threat states: examining cardiovascular, cognitive and affective responses to two distinct laboratory stress tasks. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 126, 42-51.

Tsukamoto, H., Suga, T., Takenaka, S., Tanaka, D., Takeuchi, T., & Hamaoka, T. et al. (2016). Repeated high-intensity interval exercise shortens the positive effect on executive function during post-exercise recovery in healthy young males. Physiology & Behavior, 160, 26-34. Web.

Turner, M. (2016). Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), Irrational and Rational Beliefs, and the Mental Health of Athletes. Frontiers In Psychology, 07. Web.

Turner, M., Jones, M., Whittaker, A., Laborde, S., Williams, S., Meijen, C., & Tamminen, K. (2020). Editorial: Adaptation to Psychological Stress in Sport. Frontiers In Psychology, 11.

Vogel, S., Klumpers, F., Schröder, T., Oplaat, K., Krugers, H., & Oitzl, M. et al. (2016). Stress Induces a Shift Towards Striatum-Dependent Stimulus-Response Learning via the Mineralocorticoid Receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(6), 1262-1271.

Ward, R., Lotfi, S., Sallmann, H., Lee, H., & Larson, C. (2020). State anxiety reduces working memory capacity but does not impact filtering cost for neutral distracters. Psychophysiology, 57(10). Web.

Williams, S., Veldhuijzen van Zanten, J., Trotman, G., Quinton, M., & Ginty, A. (2017). Challenge and threat imagery manipulates heart rate and anxiety responses to stress. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 117, 111-118. Web.

Wolf, O., Atsak, P., de Quervain, D., Roozendaal, B., & Wingenfeld, K. (2016). Stress and Memory: A Selective Review on Recent Developments in the Understanding of Stress Hormone Effects on Memory and Their Clinical Relevance. Journal Of Neuroendocrinology, 28(8). Web.

Wood, A., Barker, J., Turner, M., & Sheffield, D. (2017). Examining the effects of rational emotive behavior therapy on performance outcomes in elite paralympic athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(1), 329-339.

Wood, N., Parker, J., Freeman, P., Black, M., & Moore, L. (2018). The relationship between challenge and threat states and anaerobic power, core affect, perceived exertion, and self-focused attention during a competitive sprint cycling task. Progress In Brain Research, 1-17.

Wormwood, J., Khan, Z., Siegel, E., Lynn, S., Dy, J., Barrett, L., & Quigley, K. (2019). Physiological indices of challenge and threat: A data‐driven investigation of autonomic nervous system reactivity during an active coping stressor task. Psychophysiology, 56(12). Web.

Yu, R. (2016). Stress potentiates decision biases: A stress induced deliberation-to-intuition (SIDI) model. Neurobiology Of Stress, 3, 83-95. Web.

Zerbes, G., & Schwabe, L. (2021). Stress-induced bias of multiple memory systems during retrieval depends on training intensity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 130, 105281. Web.