Abstract

This mixed-methods study conducted a survey and a follow-up focus group with employees of the Uganda Public Service in order to ascertain the impact of asset retrenchment on job satisfaction. The Uganda Public Service has made a number of organizational moves, especially in recent years, to make non-productive and/or corrupt employees redundant and to bring greater efficiencies to the public sector by directing workers to where they fit best in the organization. Naturally, these retrenchment policies have created a lot of change. However, this study discovered that retrenched workers who remained in the Uganda Public Service was not less likely to be satisfied or motivated than non-affected colleagues. Moreover, job satisfaction for retrenched workers remained constant even when controlling for variables of age, gender, and education.

The Uganda Public Service likely erred in pushing through retrenchment without a formal change management strategy, as this study found that employees who had not been properly informed and/or prepared for the change were substantially less likely to be satisfied than those workers who had been prepared. One plausible reason that retrenched workers were not dissatisfied by the changes brought about by resentment may have to do with Herzberg’s (1966) Two-Factor theory, which posits that workers who are laboring for emotional satisfaction are more satisfied than those who strive for money alone. As the qualitative aspect of this study revealed, employees of the Uganda Public Service are highly likely to be providers for others, and therefore prize their jobs for giving them this ability to support others, even though retrenchment may bring change and stress. The conclusion is that Third World workforces may need to be approached via different theoretical means that are more sensitive to the non-hygienic aspects of Two-Factor Theory.

Introduction

Introduction to the Study

Uganda has been undergoing a major strategic shift in terms of its public service as a means of combating the rising corruption of the 1990s and 2000s. One aspect of this strategic shift has been the retrenchment of human assets within the Uganda Public Service, extending to the firing of several employees and the redeployment of many others. The theory behind this retrenchment has been twofold: (a) the Uganda Public Service has been seen by the government as unnecessarily large in terms of achieving its mission; and (b there is a perception that several civil servants are dead weight, and have been dragging down the performance and the image of the public service in particular and the national government in general. This dissertation studies the impact of human asset retrenchment strategies on job satisfaction, physical health, emotional well-being, and motivation in the Uganda Public Service.

The Uganda Public Service is only as good as its personnel, and it is important to know how the retrenchment strategies have impacted the workers who were redeployed. Is it truly the case that such workers feel better in their jobs, now that the department has been rendered more efficient and less encumbered by corrupt and/or underperforming personnel? Have retrenched workers experienced stable emotional and physical health in the aftermath of retrenchment? Has motivation gone up or down? Finally, what are the effects between these variables? For example, is job satisfaction correlated positively with motivations?

These questions must be answered properly, for the Ugandan government cannot afford for its remaining civil servants to become disenchanted or incapable of doing their work properly; such an outcome would lead to another exodus from the civil service, or else end up recreating the old culture of malingering and corruption that the retrenchment was designed to destroy. Thus, measuring the success of the retrenchment strategy of the Ugandan Public Service requires measuring the job satisfaction of current workers in the wake of retrenchment.

This dissertation will draw upon primary research, conducted along quantitative and qualitative approaches, to answer the question of how human asset retrenchment has impacted the job satisfaction, physical and emotional health, and motivation of workers in the Ugandan Public Service. The study will treat job satisfaction as a dependent variable and the following factors as independent variables: individual emotional and physiological differences; change management; and public policy (with each variable described in greater detail in both the literature review and the methodology). By using a combination of statistical analysis and interviewing, the study will assess the interaction of several variables in the success of the Ugandan government in retrenching the public service: The satisfaction, health, motivation, and well-being of the remaining civil servants.

Asset retrenchment is, in itself, a simple phenomenon, but one that sits at the nexus of many other theories. Therefore, this dissertation will pay attention not only to the core phenomenon of asset retrenchment but also to its interactions with organizational theory, worker psychology, change management, and management strategy (particularly performance management). Obtaining a proper understanding of asset retrenchment necessitates understanding the ways in which asset retrenchment impacts, and is impacted by, all of these other theoretical discourses.

Moreover, since the purpose of this dissertation is to examine the impact of organizational retrenchment on job satisfaction, it is necessary to doubly necessary to venture out of basic asset retrenchment theory and into the diverse literature on job satisfaction. Job satisfaction, just like asset retrenchment, is a phenomenon that is easily described, but one that touches upon many other bodies of theory. For example, it is impossible to properly understand job psychology without understanding underlying aspects of organizational theory and behavioral psychology.

It is important to be aware of these complexities at the outset, because they will structure how the literature review, a core component of the dissertation, is conducted. The literature review will begin at a high theoretical level, with a general overview that uses key literature to explain what asset retrenchment and job satisfaction are, and how they might interact with each other. The literature review will then discuss theoretical and empirical work emphasizing how human asset retrenchment creates (a) emotional and (b) physiological challenges for workers. The purpose of this section will be to demonstrate that asset retrenchment and job satisfaction are not only interconnected, but also interconnected in a way that tends to hurt workers. The next section of the literature review will explore the question of why, when asset retrenchment is a proven harm to human resources, it is necessary in the first place, drawing upon the open systems theory of the organization. Subsequently, the literature review will examine strategies—such as change management and public policy—used to minimize the impact of asset retrenchment.

Research Concepts

Asset retrenchment, which has been defined as “a reduction in assets in order to mitigate the conditions responsible for an existing financial distress” Schmitt 2009, p. 53), is an ordinary part of the business lifecycle. Both theory and observed empirical reality confirm the recurring and inevitable nature of asset retrenchment. In neoclassical economic theory as first espoused by Smith (1801), businesses acquire assets—including both capital assets such as manufacturing plants and human resources assets such as workers—in order to maximize their ability to serve market demand. Thus, when that demand flags, businesses no longer require the same amount of assets. Empirical observation confirms this theory; many researchers have confirmed that, when market demand is suppressed—for example, in a recession—asset retrenchment is one of the most frequent responses (Morrow, Johnson, & Busenitz 2004).

Asset retrenchment can also be prompted by a number of factors other than demand suppression. For example, an organization can undergo an internal crisis requiring retrenchment. Pearce and Robbins (1993) have explained that asset retrenchment can therefore be thought of as a common strategy for business turnaround, regardless of whether such a turnaround has anything to do with an external demand crisis or not. Furthermore, Gupta and Sathye (2010) have pointed out that asset retrenchment can take place in government just as in the private sector, and that asset retrenchment in the public sector can be due neither to an external demand crisis nor to an internal turnaround, but simply to a change of political regime. As such, it is clear that asset retrenchment is a common feature of both private and public sector organizational activity, and that it can be prompted by any number of stimuli.

Job satisfaction refers to a worker’s self-perceived enjoyment of work, enjoyment that can be measured along any dimension that it important to the worker. There are a number of studies on job satisfaction (see Herzberg 1966 and Vroom 1964) demonstrating that the greatest job satisfaction comes from a feeling of emotional fulfillment and self-actualization.

It is equally clear that, when asset retrenchment involves firing and/or redeploying human resources, it can be a fairly traumatic strategy in terms of impacting job satisfaction. The theoretical basis for this conclusion can be found in organizational psychology as well as behavioral psychology. In organizational psychology, a number of theorists have argued that workers draw motivation from understanding and relying upon a specific role in the workplace (see for example). Thus, when workers are fired or redeployed, their worlds are shaken; at least in terms of professional life, they no longer know where they belong. Meanwhile, behavioral psychology suggests that human asset retrenchment is biologically traumatic. Being fired or reassignment generates tremendous change in an employee’s life, and change has been empirically linked to stress and a number of adverse physiological consequences, ranging from heart attack to diabetes, as the upcoming discussion will demonstrate.

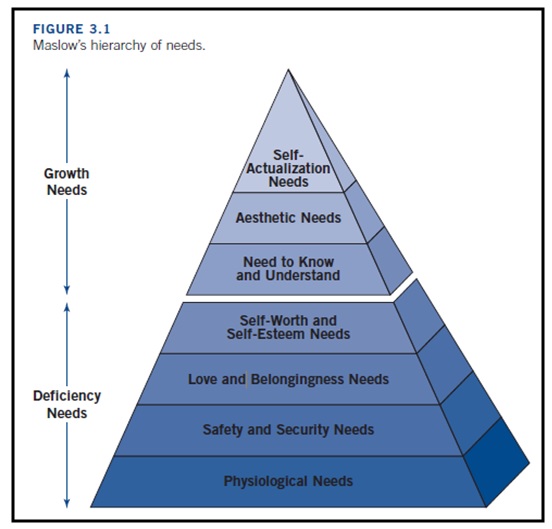

Thus, theories of organizational psychology focus on the emotional impact on the emotional impact of asset retrenchment of human resources whereas behavioral psychology emphasizes the physiological impact. Both of these fields suggest that asset retrenchment is hurtful for the worker, albeit from different perspectives. Additionally, there is a single theory that brings together organizational and behavioral psychology in a unified explanation of how asset retrenchment impacts job satisfaction. Herzberg’s (1966) Two-Factor theory, in conjunction with Maslow (1993) and Vroom’s (1964) theories of worker satisfaction, predicts that retrenchment hurts job satisfaction along two separate but complementary axes, namely by hurting: (a) what Maslow refers to as the lower rungs on the hierarchy of needs, such as the ability to earn food and win shelter; and (b) what Herzberg has referred to as the emotional satisfaction of work.

However, there are other bodies of theory that explain how the negative impact of asset retrenchment on workers can be mitigated. For example, the theory of change management predicts that, if workers are prepared for and shepherded through the change appropriately, their trauma will be less. Additionally, public policy theory predicts that government resources can be used to minimize stress to workers; for example, laid-off workers can receive benefits and retraining, whereas workers who are still on the job can draw upon free counseling and other possible public services to help weather the changes.

This overview suggests that, according to inputs from numerous theories, it is not a foregone conclusion that asset retrenchment of human resources will lower job satisfaction, as change management and public policy can be used to offset the natural emotional and physiological harms that are generated by asset retrenchment. As such, in any environment in which assets have been retrenched, individualized measurements will have to be carried out to determine whether the organization was able to overcome the negative impacts of retrenchment.

Importance of the Study

The research carried out in this study is clearly of great value to Uganda. However, it is also of value in general academic terms, as it is a rare empirical contribution to the largely theoretical literature on asset retrenchment. As such, the research can be used not only in the context of Ugandan public policy but also by any theorist or business practitioner who wishes to understand the impact of retrenchment on job satisfaction.

The research problem and questions

The study will focus only on public service workers who have been reassigned or whose job descriptions have otherwise altered as part of a retrenchment strategy. The study will not extend to workers who were fired as a result of retrenchment.

Research objective: To gain an understanding of the impact retrenchment on different aspects of job satisfaction of survivors.

Research question: What is the relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction?

- H10: There is no relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction.

- H11: There is relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction.

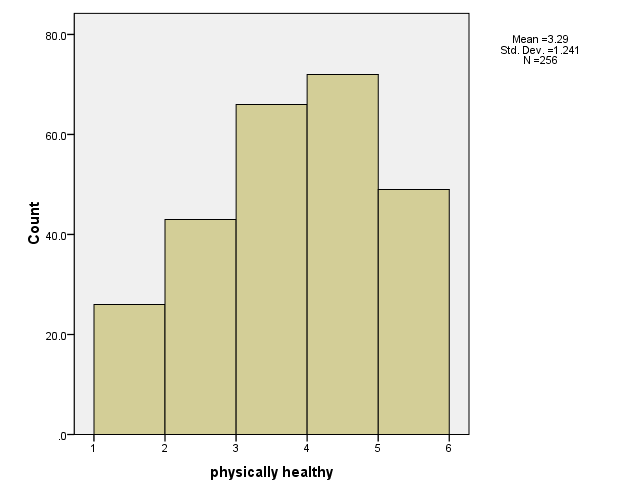

- H20: Retrenchment has no physical impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H21: Retrenchment has physical impacts on survivors in the short-term.

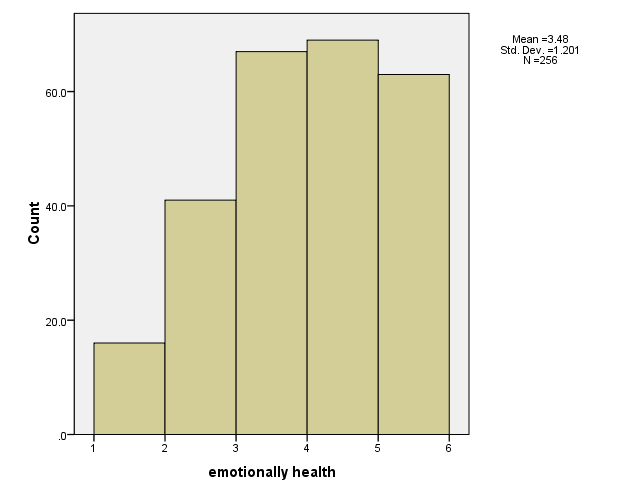

- H30: Retrenchment has no emotional impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H31: Retrenchment has emotional impacts on survivors in the short-term.

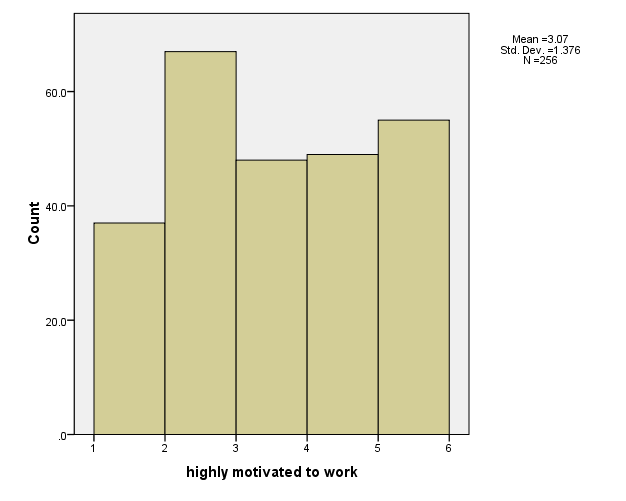

- H40: There is no relationship between retrenchment and motivation in the short term.

- H41: There is relationship between retrenchment and motivation in the short term.

- H50: There is no relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction in the short term.

- H51: There is relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction in the short term

- H60: There is no relationship between Survivors’ syndrome and job satisfaction

- H61: There is relationship between survivors’ syndrome and job satisfaction

Overview of all chapters

This research project intends to measure the relationship between asset retrenchment strategies and job satisfaction for employees of the Uganda Public Service. This research consists of five chapters which will cover the objectives of the research topic.

In this chapter, the introduction outlines the purpose and the scope for the research project, and the main objectives are clearly explained and justified. The research questions were suggested to carry out an empirical investigation into the relationship between retrenchment strategies and job satisfaction. The literature review gives contextual setup of the study as well as the background which form the basis of for the solution to the research questions. The section will include academic learning theories based on job satisfaction with present dimensional measures to measure satisfaction in the workforce. Furthermore, retrenchment strategies that many organisations are using especially in a recession market will be included. a conclusion will be underlined the relationship between retrenchment strategies and job satisfaction in with employees. Chapter three evaluates the relevant research methodology that will be used to obtain the necessary information to be able to answer the research questions. The methodological approach will discuss the operationalisation of the hypotheses and the research instrument to be used to collect the data.

In the critical analysis chapter, analytical discussion will be applied to the sampling techniques using SPSS software version 14.0 to analyze the data and describe the tested hypotheses.

Literature Review

Introduction

The subject of the discussion is not asset retrenchment, per se, but rather the effect that specific aspects of asset retrenchment such as change management approach, leadership style, and impact on workers’ job descriptions has on workers’ physical health, emotional health, motivation, and satisfaction. This section seeks a general overview of jobs and circumstances occasioned by the loss of it by retrenchment. An employee is one of the major assets that any employer will have; they act as the principal source of labor that keeps the organization in motion. Their contribution and efforts determine how effective the organization’s production is.

The bond between the employee and the employer is mainly held by the exchange between the two, the former provides labor while the latter rewards in form of remuneration, promotions incentives and other benefits. The reward must be commensurate with the effort put. Vroom (1964), argues that “there is job satisfaction if there exists a positive correlation between efforts and performance and reward, favorable performance leads to a desirable reward, the reward must be a proportional reflection of the effort and performance”. If the employee rates the reward as below expectation, this will lead to dissatisfaction and low performance. This affects the overall production of the organization. There are three major pillars that help in better understanding of job satisfaction.

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction can be divided into three. Valence is what the employees hold emotionally, they are the core reasons for one taking up employment this are factors like remuneration, all employees will look for the most rewarding available employer who will offer the best package. Therefore, it is expected that they will put maximum efforts and in return get maximum benefits. Promotions are necessary as all human beings work for upward mobility, if a worker stays in one position without getting promoted the job gets dull and less satisfying. Job stagnation leads to low esteem and low morale which will lead to poor performance. Every worker is entitled for a time off, this facilitates the individual to rest and also handle their personal affairs. If this is denied absence the worker will be more dissatisfied and that automatically will impair their production. Apart from the regular payment, workers who get other benefits will be more satisfied as opposed to those who get the regular pay only. Even if the regular pay is huge it might not be as satisfying as a smaller pay which is coupled by several other benefits. Employees will always use this as the yard stick to measure how much the employer values them. If the above are availed, the employees’ life beyond work gets a shot in the arm, they have better living standards and hence thy have high regard for their employment and this leads to higher productivity.

Expectancy is what the employee expects from the employer, this comes in form of knowledge and new innovations, it is expected that employers provide refresher courses, retreats, and other forms of supplementary training in order to enhance the employees’ skills and productivity. An employee who benefits from these will exhibit higher signs of job satisfaction as opposed to the ones who get little or none of these. Instrumentality can be described as the perception the employees have on their boss, this manifests its self if promises are kept, if a reward was promised and given, the employee will have a high regard for the employer and this will increase satisfaction and production. However, if a promise is never fulfilled, employees will feel cheated and hence there will be no job satisfaction which will result to low morale and subsequently low production.

Microsoft’s approach to the issue of instrumentality should be considered a best practice in this regard. When Microsoft sets a ship date for its software, it adheres to that date no matter what transpires. Engineers conducting periodic reviews of the work to date are empowered to cut down functionality requirements if doing so will enable the ship date to be met. This strategy addresses the problem of instrumentality as described above because, when workers realize that they have been given an impossible task, they redefine the task to make it possible. Far from being an admission of failure, such an approach makes it possible for the software development team to work free from the pressure of the impossible, to feel as if it always has the instruments necessary to do the job at hand. This principle can apply to the public sector as well. If all these are well taken care of the employee will feel that the employer understands what they value as well as understand their worth. Once the employer avails this, job satisfaction is achieved.

Job satisfaction is one major factor to determine amongst other factors the employees’ motivation which impacts heavily on production capacities as well as employees turnover. Employers whose institutions have little or no job satisfaction will always experience high turnovers as employees seek employment in other areas in pursuit of job satisfaction.

Motivation and Job Satisfaction

The discussion of motivation and satisfaction was collapsed into a single section because, according to the theories that will be examined in this section, motivation and satisfaction have the same psychological roots, particularly in organizational contexts. There is strong empirical evidence that there are two separate pathways that determine how people work. Herzberg’s (1966) Two-Factor theory established that hygiene and satisfaction are the two separate axes that explain workplace motivation

A human being spends a third of their lives at work, this calls for a very satisfying environment least an employee spends this huge chunk of life dissatisfied and automatically this will lead to impaired production In any undertaking motivation is key as it hold production as well as job satisfaction. Workers needs and wants must be met so as to attain satisfaction. The psychological needs must be taken care of an employee need to be contented in what they are doing the job and tasks must be at per with the qualifications, if one is given a task with a low description, it will lad to a situation of dissatisfaction, on the other hand if the task is way above the capabilities of the employee they might feel overrated and this will also lead to dissatisfaction.

Herzberg (1966), in drafting his theory, argued that “someone who is motivated is truly a sight to behold, as they put all of their heart and soul into an activity. Love of work is certainly the strongest motivator of people”. He was both a theorist and an empirical investigator and conducted workplace surveys that demonstrated the distinction between hygiene and satisfaction. Hygiene refers to those aspects of a job that are the most basic like salary, physical workspace, security etc. Satisfaction refers to those aspects of a job that generate some form of emotional satisfaction for the worker things like good remuneration, benefits and perks amongst others. This theory has been empirically confirmed by different researchers, including Cenfetelli (2004) described hygiene as ‘inhibitors’ and satisfaction as ‘enablers’ in the human’s ability to perform. This language is important, as it helps to explain what lies at the heart of workplace motivation. Hygiene is an inhibitor, in that it, when it falls below, a certain standard, it can cause people to quit or become unmotivated. However, merely raising hygiene to a certain level does not automatically translate into satisfaction (in Herzberg’s 1966 term) or enablement (in Cenfetelli’s 2004 term). “More money does not mean more happiness”.

Nissle and Bschor’s (2002) empirical study demonstrated that even winning the lottery did not often reverse depression among winners. While paying someone more money may prevent them from leaving a job, the simple fact of a higher salary cannot make a boring job satisfying or translate into automatic emotional fulfillment for the worker. That, in a nutshell, is Herzberg’s theory, and its empirical confirmation by a host of researchers (including Nissle & Bschor) has rendered the theory one of the well-confirmed constructs in all of organizational science. Turner’s (2003) work, which assessed the existing state of compensation theory, came to the conclusion that today’s employees are increasingly in search of satisfaction, and there is a marketplace of opportunities for good employees who do not find satisfaction at their current jobs. A cynic might ask: Why is it important to motivate employees?

Aguayo (1991) has provided the answer, based on a survey of productivity, compensation, and quality statistics: “intrinsic motivation is the engine for improvement. If it is kept alive and nourished, quality can and will occur. If it is killed, quality dies with it” (p. 103). That is why, according to Arthur (2006), HR recruiters tend to look for intrinsic motivation as one of the most important potential employee qualifications. Herzberg (1966), meanwhile, argued for a distinction between what he called movement and motivation (p. 141). “Movement is what ordinary employees do in order to give their bosses the illusion that they are active; movement is designed to give off more light than heat, and stay employed. Motivation, on the other hand, is true enthusiasm, the force that allows people to move mountains, in both the professional and personal lives”.

Some organizations fail to be able to offer benefits and conditions that can emotionally satisfy employees into being motivated rather than ‘moving’ because, after all, benefits also cost the business money. Having on-site gyms, no less than providing high salaries, requires deep pockets from the business providing it. However, the literature accepts that existing employees who are asked to give up either hygiene or satisfaction in the workplace may give their assent if five questions are answered form them. These five questions, according to Jensen and Kerr (1995), attempts to explain the following: “Why must we change and why is this change important, What one is supposed to do, What are the measures and consequences of change or lack of it, What tools and support will be available to the employee, and what the employee ca expect” (p. 411). Based on an empirical study of workers and lower-level managers, Sims (2002) concluded that, if the Jensen and Kerr questions are not answered, then it is likely that the response of employees to requests for change will be one of “resistance and cynicism” (p. 202).

The literature has many profound implications and few gaps, as there is by now over half a century of dense research on the topic of employee motivation. The first important implication is that emotional satisfaction is the most important component of workplace satisfaction and motivation. Based on the theories put forward by Maslow (1993), and empirically confirmed by Herzberg (1966) and his followers, people who are emotionally satisfied with their work are the more likely to leave employment and the most likely to excel at it. This research should inform the HR manager that the key deliverable of a compensation and benefit strategy ought to be the generation of emotional satisfaction for employees.

There are a number of specific explanations, which are complicated by the fact that, for different people, motivation results from different things. However, what both Maslow and Herzberg found is that factors such as money are fairly down the list in terms of conferring self-fulfillment. More recently, Bandura (1997) has found that self-efficacy is a very important component of self-fulfillment, although one that is difficult to achieve:

Efficacy is a generative capability in which cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral subskills must be organized and effectively orchestrated to serve innumerable purposes. There is a marked difference between possessing subskills and being able to integrate them into appropriate courses of action and to execute them well under difficult circumstances. People often fail to perform optimally even though they know full well what to do and possess the requisite skills to do it (pp. 36-37).

There is no greater pleasure than doing a difficult and rewarding job well. On the other hand, it seems that there is no greater disappointment than failing to do such a job either because the sub skills or the job resources are not present. Bandura argued that it is not enough for the skills to be present; an employee must know that the skills are present.

If one of these factors is absent, the results will be dismal for they are all important and hence should be applied as a cocktail. The working environment must be safe; this assurance helps in motivating the workers as they execute their duties without fear of any risks and eventualities. Workers also need to feel that they belong to an organization; this can be achieved by the employer contributing to aspects outside working environment. If an employer provides medical cover, the employer feels that their plight is of importance and this motivates them. The esteem of an employee is of importance and is a major factor in their motivation. The way issues that arise in the course of duty are handled will determine the levels of motivation.

If an employee makes a mistake and is bashed or unjustly punished by the superiors, chances are that they will feel belittled and that affects their esteem. There are set goals and standards which are supposed to be attained, if an employee is unable to match these standards in the course of their duty dispensation, and the management fails to come up with strategies to help in rising the standards, the employee might not attain their full potential and this will lead to low motivation. In addition to instrumentality, another foundational component of motivation is equity. In equity theory as applied to business, the idea is that workers are not altruistic in their motivation; not surprisingly, they will put in what they think they are getting back from their employer (Adams 1976). In what is known as equity theory, the dependent variables of worker performance, motivation, and satisfaction are all predicted, to some extent, by what the worker perceives as receiving from the employer. The original graphic in Figure 2.1 depicts equity theory in action.

In expectancy theory, motivation is driven by an employee’s knowledge that a first-order action—like working hard—will lead predictably (and fairly, which is where equity theory comes in) to a second-order outcome, like a reward (Montana and Charnov 2000, p. 250). Equity theory complicates expectancy somewhat, as different employees may have different ideas about what is fair. A particularly egocentric person working 10 hours a week might expect a giant salary. However, equity theory can’t even kick into action until the instrumentality component of expectancy is satisfied. After all, Vroom’s theory (1964) predicts that force = first-level valence x expectancy, but expectancy can only take place if instrumentality is present; if we do not expect, or if it is not true in fact, that a first-order behavior will lead to a second-order outcome, expectancy will be nil, thus translating into zero force (meaning that the employee is not at all motivated to work).

In the theory of organizational psychology as proposed by Vroom, instrumentality is just the beginning of motivation. It is not enough for workers to feel that they can do their work. Equity theory and other motivational techniques must now be applied to ensure that workers will do their work. So how should an HR manager company apply the theory? The first step is to understand what theories of motivation have been proposed, which has been the task of this section of the paper. To briefly recap: Frederick Herzberg’s Two Factor theory has been particularly influential in its claim that job satisfaction is directly related to a class of motivators that includes recognition, advancement, and growth. Herzberg’s theory, read in conjunction with Maslow’s notion of a hierarchy of needs, represented a fundamental shift in motivation theory, which had previously posited that factors such as salary and working conditions were more important determinants of job satisfaction and, thereby, improved performance.

After Herzberg and Maslow, most scholars in organizational psychology concur that money is just one element of satisfaction, and not the most important one. In strategic HR, then, it is necessary to pay attention to emotional satisfaction, instrumentality, self-efficacy, equity, and expectancy theory in order to cover all the bases of employee motivation and to reap the rewards that Aguayo (1991) and others have empirically documented as coming from a highly motivated workforce.

Causes of Job Satisfaction

The causes of job satisfaction are all found within the job itself. Satisfaction is determined by the discrepancy between individual’s idea of an ideal job and what the market is currently providing or the job currently being held. How one values an assigned task and the attitude towards it determines satisfaction. Workers need autonomy, the more autonomous a worker is the more satisfied they become. Ability to successfully complete a task will also determine satisfaction. The employees’ perception towards what they do, their superiors and what they earn, will also determine job satisfaction. If an employee feels underpaid will tend to exhibit dissatisfaction tendencies, if one’s boss is nasty it will also lead to dissatisfaction.

Another factor is how an employee perceives their job; there are those who feel that, whatever they are doing is demeaning and that they should be doing better things. If the organization creates a conducive working situation where by as per the equity theory there is fairness, good remuneration and the employee is made to feel appreciated, there will be high tendencies if job satisfaction. This lesson is extremely important for the HR manager to understand. If workers feel that they are being given impossible tasks, they will become unmotivated and no other measure that the company takes—salary bonuses, worksite perks, etc.—will overcome the sense of hopelessness and inertia generated by the loss of instrumentality. “The problem is that the very nature of modern work can involve difficult or even impossible tasks conducted under the stress of deadlines” Peterson et al.(2000).

Two-Factor Theory

Herzberg (1966) advanced what is known as Two-Factor Theory, which is highly indebted to the concept of the hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1993) and adapted specifically to the workplace context. Herzberg agreed with Maslow on the differentiation of needs. To Herzberg, the foundational needs could be grouped under the heading of ‘hygiene.’ In a working context, such hygienic needs included the basic needs required by people to do their jobs: Wages, a proper working environment, medical benefits, and so forth. But, according to (Herzberg), “people do not obtain their greatest satisfaction from hygienic needs. Instead, workers feel most fulfilled when they reach the top of Maslow’s pyramid”. In other words, they are at the highest peak of their careers when their work is profoundly satisfying to them on an emotional and personal level. He also argued that emotionally satisfied workers were likely to do work of a higher quality than workers who were just meeting their hygienic needs.

Researchers Vroom (1964) and Alderfer (1972) found that, “work satisfaction is primarily emotional and satisfaction and performance are connected”. This dissertation, too, will determine whether there is a statistically significant link between performance and satisfaction in the context of the Ugandan civil service. Herzberg’s theory is useful in theoretical foundation for the linkage between performance and satisfaction, it is also aids in differentiation of the hygienic from the truly satisfying. He predicts that, in every job, workers will require certain hygienic factors to be there (for example, a paycheck), but will not be ultimately motivated or satisfied by these factors. Instead, there will be higher-order factors that actively engage and fulfill a worker.

Many people work not because of positive reasons say, liking what they do but because of negative reasons like being afraid of losing a paycheck. Here is a hypothetical example of this two-factory theory in action: A public service worker who fundamentally dislikes his job is given a raise. The raise keeps the worker from becoming even more dissatisfied; however, it does not excite the worker about reporting in to work every day. The worker still finds his job unsatisfying and unfulfilling; however, because of the paycheck, the worker remains in the position. This dynamic, according to Herzberg, plays out in millions of workplaces. Many people work not because of positive reasons (i.e., really liking what they do) but because of negative reasons (i.e., they are afraid of losing a paycheck). A smaller number of people work because of positive reasons; these people, Herzberg and Maslow argue, are the ones who are really happy. The framework provided by Herzberg will be used by this dissertation in order to differentiate between reasons for satisfaction and reasons that merely keep workers on the job, regardless of satisfaction.

Measuring Job Satisfaction

It is important to measure job employee’s satisfaction so as to ascertain their attitude in relation to work. This will help in understanding the levels of employees’ satisfaction as well as help in crafting policies that will boost job satisfaction by identifying weak points as well as help in explaining an employee’s production and that of the company. Several methods are applied in measuring satisfaction, many at times the process is intertwined in the appraisal process. The appraisal is used to camouflage test for purposes of honesty. Employees fill in questioners with yes/ no questions, true or false system, checklists or forced answer questions. Job Descriptive Index (JDI) is another method that seeks an employee’s satisfaction in five areas, pay, promotion and opportunities, colleagues, supervision and the actual work. There is even an alternative way through the use of General Index which is a higher version of JDI and lays emphasis on the individual experiencing the effects while overlooking other factors. Minnesota Satisfaction Questioner (MSQ) tests 20 factors, in the working environment, the employees’ social and economic life. This should be done regularly and it should be done in a professional manner. There should be a report on findings as well as recommendation so as to address the contentious issues.

Asset Retrenchment

At times organizations find themselves in situations where by the staff ratio gets high compared to production. This necessities downsizing where a portion of the labor force is declared redundant. Retrenchment is the exercise used to send home under a negotiated or a given package. Organizations and the representatives of the departing batch get in to talks to come up with an acceptable terms. However it is not always that the affected lot is called into talks. In the early 90s after the end of the cold war, most third world countries were faced terrible financial crisis, when they went to the Bretton woods Institutions for aid, amongst the conditions given in order to aces aid was government restructuring which called for laying off some workers. Many governments never consulted; instead they imposed upon the leaving lot a package. Some of the reasons that occasion a retrenchment include, (a) change management; (b) leadership style; and (c) changes in workers’ job descriptions.

Change Management

Change is a dauntingly complex concept, one that can mean everything from a “succession of one thing in place of another” to “death,” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2008) and, as Shakespeare used the word, even a variety of dance (1598, p. 198). In the business context, change is all of these things. Change is a succession of one thing in place of another in increments of hours, weeks, quarters, and years; change, insofar as it arouses deep fears and paralysis, is death; and, most empowering, change is also a dance that, in partnering the business with the great unknown of the future, requires equal parts agility, planning, and determines to execute properly.

Change management is an equally complex undertaking, one that requires establishing the strategic rationale for stakeholder commitment to change that defines approach to change on the ground; mapping the ways in which change touches and challenges the assets, human and otherwise, of the business; and managing accommodation to change at the tactical and operational levels. Change management is one of the factors that occasion retrenchment; it is an occurrence that is inevitable. Some factors that influence these changes include, change in ownership, dismal performance, departure of top management and mergers amongst other factors. “All organizations practice change management, because businesses and managers are faced with highly dynamic and ever more complex operating environments that require constant adjustment of existing plans, procedures, and policies” (Paton and McCalman 2000, p.43).

Change management is not something that takes place haphazardly but is governed, this is to cushion the organization from any negative side effects. The fact that 70 percent of change programs fail is a testament to the fact that most companies take the haphazard approach to change management. (Balogun & Hailey, 2004) “Change in the organization is dependent upon a new model of information, which often means that new information must be acquired from the world outside” To advocate a change management strategy is not simply to suggest ways in which the business can respond to changes, but rather how it can integrate human resources management since it is core to all this activities. According to Ulrich (1997), “capacity for change” is one of HRM’s four deliverables. The other three deliverables—executing strategy, achieving administrative efficiency, and managing employee contributions—all touch change management as well. For this reason, HRM ought to be considered and approached as a trusted advisor by executive management in any discussion of change management. Such discussions extend to personnel decisions with the executive suite itself: “…when a business is pursuing a growth strategy it needs top managers who are likely to abandon the status quo and adapt.…insiders are slow to recognize the onset of decline…so top managers need to be recruited from the outside” (Schuler & Jackson 1999, p. 159).

These prescriptions are just as valid for the public sector as the private sector. “This can be triggered by unpredictably shifting conditions, while Planned change is triggered by the failure to create continuously adaptive mechanisms, this occurs under conditions of perceived failure” (Morgan & Zeffane 2003). It is for this reason that change must be embedded in the strategic plan of the business. The business can rectify these omissions by drafting a change management approach that encompasses people, markets, strategies, and computers. The business must think about, anticipate, and simulate change scenarios in all of these categories individually, and in combinations of the categories. This means not only drafting specific contingency plans for managing change say if, top executives should depart or the price of doing business increase or new laws affect the market or such situations, how changing market conditions will impact any restructuring of the employee base but also inculcating a healthy spirit of improvisation throughout the organization, so as to develop a culture of resilience in the face of change. In this way, change management supersedes reengineering.

Reengineering applies to specific and discrete projects, whereas change management is a philosophy that permeates the enterprise (Worren, Ruddle, & Moore 1999). Moore discuss the ways in which reengineering guru Michael Hammer “forgot about people” while organizational development (OD) people “now concede they forgot about markets, strategies, and computers” (p. 284).The business can rectify these omissions by drafting a change management approach that encompasses people, markets, strategies, and computers. The business must think about, anticipate, and simulate change scenarios in all of these categories individually, and in combinations of the categories.

This means not only drafting specific contingency plans for managing change (if, for example, top executives should depart, the price of doing business increase, computer systems fall behind those of competitors’, etc.) and cascading change (i.e., how changing market conditions will impact any restructuring of the employee base) but also inculcating a healthy spirit of improvisation throughout the organization, so as to develop a culture of resilience in the face of change. In this way, change management supersedes reengineering. “Reengineering applies to specific and discrete projects, whereas change management is a philosophy that permeates the enterprise” (Worren, Ruddle, & Moore 1999).

The academic literature suggests that the role of HR is not only to assist in the crafting of high-level strategy but also to help translate that strategy into an actionable plan. Assuming that the core mission of HRM is to manage “the pattern of planned human resource deployments and activities intended to enable the firm to achieve its goals” (Wright & Mac Mahan 1992, p. 298), HRM’s more specific role in this domain is to serve as the “vertical fit [responsible for] directing human resources toward the primary initiatives of the organization” (Wright & Snell 1998, p. 756). HRM’s job is therefore to be “concerned primarily with developing the organizational capability to adapt to changing environmental contingencies” (Snell, Youndt, & Wright 1996, p. 61).

As a mapmaker, then, HRM takes inputs from executive management strategy and helps translate them into actionable outputs for the enterprise. In doing so, one of the key responsibilities of HRM is change management. HRM proceeds according to the belief that, in a business with integrity, the thirteen possible sources of resistance to change (Eccles 1994) can be overcome at the operational level by properly communicating the necessity for change, and all the attendant benefits. After mapping comes execution. Executive management has articulated a strategy, HRM has helped to map out and communicate that strategy, and finally it is time for implementation on the ground—that is, at the tactical and operational level. Primarily, this involves handing off responsibility: “Strategic planning and change leadership are the realm of executive management. Tactical projects are (usually) the realm of first-line managers and employees” (Williams 2000, p. 60).

According to Wright and McMahan (1992), “HR’s central function is to manage human resource deployments in order to achieve strategic goals”. Snell, Youndt, and Wright (1996) have added the insight that this management must be sensitive to issues of strategic change. Since Aguayo (1991) argued that employee motivation improves work quality, HR must manage employee motivation if one of the overarching strategic goals is to achieve higher quality. The literature on change management suggests that the role of HR is extremely important in planning for change, communicating it, and managing it. This point has been absorbed into the fabric of the study by means of emphasizing the role of HR in the manager-facing version of the survey (Appellbaum 1999).

Leadership Style

It is common for one to confuse leadership and management for it seems that the two are almost complementing. Forster (2005) offered an excellent definition in this regard:

Leadership is usually concerned with what needs to be done—management often focuses on how things should be done. Hence, a manager would focus on how quickly and efficiently an employee climbs up and down a ladder to perform a task. A leader would be primarily concerned with determining whether the task was appropriate in the first place, or if the ladder was leaning against the right wall, or if there was a better way to get up the wall (p. 5).

Authentic leadership is held to be an important model of true leadership. What can be termed as authentic leadership is closely related to the concept of integrity. Other scholars have made the same point. For example, Grover and Moorman (2007) have argued that authenticity in leadership is synonymous with integrity. Ladkin and Taylor (2010) offered the following insight, which is quoted in its entirely because of its great explanatory power:

Producing embodied authentic leadership, we’ve suggested, is not a straightforward process of merely ‘expressing one’s true self’. Instead, it involves the balancing and resolution of paradoxes and tensions, many of which have their origin in bodily and unconscious processes. For instance, a leader may authentically be experiencing fear and uncertainty, as well as excitement and hope in the face of organisational catastrophe. Enacting one’s ‘true self’ in such situations calls for leaders to balance how they might express something of the complexity of their competing emotional and bodily reactions in a way which is experienced as ‘leaderly’ for those looking for guidance in those situations. Similarly, enacting one’s ‘true self’ necessarily places the leader in a vulnerable arena, with the corresponding benefits and difficulties associated with such potential insecurity. How does a leader maintain such a position, while acknowledging that in doing so, they may leave themselves open to attack? Perhaps the greatest challenge to embodying authentic leadership is faced as leaders resolve the tensions that will occur between their individual, truly felt commitments and the identity needs of the group which they lead (p. 56).

There are a number of helpful (and disturbing) concepts in this passage. First, Ladkin and Taylor suggest that authenticity is not merely real feeling; it is the staging of real feeling, which itself takes place along a continuum of authenticity. Staging means that the leader is aware that his feeling is not just an internal state specific to her, but a product for public consumption. Thus, a politician who allows herself to cry on the campaign trail is not merely having a genuine feeling, but also domesticating and packaging that feeling for the consumption of others. Authentic can be mixed with that of the actor, and leaders are expected to balance between the two. Authenticity is part of what Avolio (2007) has called a “schema of leadership” (p. 25). It is not naïve and unpremeditated behavior; rather, it is a balance between what the leader feels and what the leader needs others to see that she feels, distinguishing it from an unperformed, private authenticity. Granted, some scholars differ from Ladkin and Taylor (2010). For example, Nohria and Khurana (2010) emphasize a difference in substance between the authentic and inauthentic leader: “The pseudo-transformational leader looked like the transformational leader but was not genuine; he or she was able to display transformational qualities and actions, but did not have the moral basis for being transformational” (p. 745).

In this account, authenticity ceases to be a kind of spectrum, as it was envisioned, and instead becomes an absolute state: one is either authentic, or one is not, and there is an iron distinction between shadow and substance. There are other theories of leadership in addition to authentic transformational leadership. For example, the notion of transformational leadership is particularly prominent in the literature. Perhaps the best way to define a transformational leader is to define leadership and transformation separately, and then to examine what one has to do with the other. Trofino (1995) champions the concept of a leader as someone who influences others towards the achievement of a common goal (p. 44). According to Trofino, while the leader is the visionary and the motivator, the manager is the one who makes sure that the organization executes the steps needed to get to the goal. Amabile and Khaire (2008) do not provide a single definition of transformation, but they emphasize innovation as one of its core components (p. 103). “In an organizational context, then, transformation can be thought of as the set of processes needed to innovate—that is, to change in response to new conditions, stresses, and constraints”. While Amabile and Khaire dwell on older examples of innovation, the fact is that present-day organizations are faced with what could be called permanent transformation.

There are a number of reasons for this development. Competition is more intense than ever before, meaning that organizations must keep up with their rivals and peers in order to stay relevant. Business conditions are challenging, with customers, suppliers, and organizational stakeholders constantly shifting allegiances, and the costs of business always in flux. Technological progress is so rapid that it constantly changes business models; the emergence of the Web, and the recent appearance of social networking, is two examples of technological transformations that force businesses to innovate. For these reasons, a transformational leader is not necessarily someone who pulls off a one-time change, such as presiding over the computerization of a previously manual workplace. A transformational leader is, rather, someone who influences others to cope with, and indeed to master, the day-to-day changes that impact an organization. A transformational leader is someone who understands change, and who can equip and motivate others to keep pace with change while keeping an eye on the organization’s ultimate goals.

The ideal organizational culture needed to support transformational leadership is a flat environment in which leaders do not bully followers, emphasizing the connection between democracy and transformational leadership. Vroom (1990) puts it this way: “As long as anyone in a leadership role operates with a reward-punishment attitude toward motivation, he is implicitly assuming that he has (or should have) control over others and that they are in a jackass position with respect to him” (p. 84). Alas, this faulty and unethical approach to leadership is everywhere, and will have to be rooted out of organizational culture for transformational leadership to be effective. The survey of leadership concepts in this section helped to break out the otherwise monolithic idea of leadership into sub-categories, such as authentic leadership, transformational leadership, and democratic leadership. Ugandan workers in the sample will be asked about the ways in which their managers have, or have not, demonstrated these kinds of leaderships, and the results will be employed to help determine if leadership style is a mediating factor in the influence that asset retrenchment exerts on worker health, well-being, motivation, and satisfaction. The most important aspect of leadership is the ability to handle all situations in a way that the organization continues and remains stable.

Retrenchment Impact on workers

Retrenchments will usually have far reaching implications to the quality of life of the remaining workers. It is not always that what the leadership aimed to achieve will be the only thing that is gotten, there are several side effects that will affect the organization both positively and negatively. When retrenchments occur there is usually lots of apathy within the organization this brings down the morale and motivation and this cuts across board from the subordinates to the seniors. This situation will always have a big impact as it cuts down production (Cook and Warr (1979). Job satisfaction amongst the remaining workers is also affected as some section feels insecure since the believe the same fate can befall them while others felt that they are made to bear a large work load that could have been otherwise done by the retrenched staff. It is expected that after such an exercise, the remaining workers commitment to the organization should improve so as to better their appraisal. This is not the case however, some workers feel more detached and their commitment dwindles. One area that makes retrenchments unpopular is the fact that there is no change in remuneration and ability to meet their financial obligations. One of the reasons that drive organizations to retrenchment is cost cutting and hence the surviving workers gain nothing. One big creation of retrenchment is the creation of job insecurity, the survivors will live perpetually feeling that the next job on the line is theirs this adds to low morale (Victor 1964).

Physical and Emotional Impacts

Both physical and emotional impacts are studied together as literature often treats them as complementary or over overlapping. Human beings perceive of any kind change, positive or negative to be stressful, even to the point to debilitation. The connection between change and stress is so well-confirmed that social scientists have a hybrid term for it: life change stress (Hurst, Jenkins, & Rose 1978). There is even a sort of cyclical relationship between stress and change; for example, change causes stress to the human immune system, which in turn changes both the body’s physiology (rendering people more susceptible to colds) and psychology (for example, by generating depression). Locke, Kraus, Leserman, Hurst, Heisel, and Williams (1984) documented the connection between stress and immune system weakening, while Stewart and Salt (1981) empirically proved the connection between change-induced stress and depression. Interestingly, there is only a minor difference between the effects of so-called good versus bad change; in both cases, people report stress as a consequence from an organizational perspective, Munsch & Wampler 1993).

As a fascinating illustration of the power of even good change to result in stress, consider that there are many documented instances of lottery winners suffering from depression in the aftermath of winning (Nissle & Bschor 2002). The most important points are about how the resulting stress manifests itself and how it can be defused, the precise manifestations of stress depend on factors such as people’s relative standards as well as cultural variables. For example, people who are very poor and expect very little in terms of life may not be greatly surprised by change, such as the closure of a factory; in other words, people with low relative standards are also the least likely to respond adversely to change and stress, because change and stress are already pervasive factors of their lives. Culture is also an important factor, for example, societies that tend to respond stoically and non-emotionally to stress may find it easier to manage change, whereas people from emotionally voluble cultures may be inordinately traumatized by change. However, it is also important to anticipate how stress can manifest itself in real life, so that responses can be further customized to specific victims and their needs. After every retrenchment what sets in is the survivor syndrome which affects the organizations production.

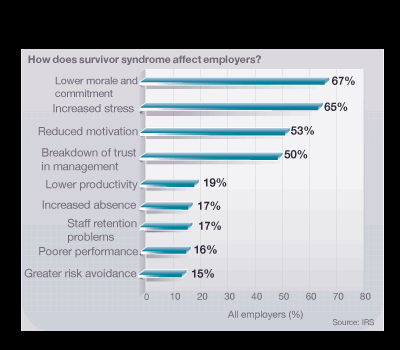

Survivor’s syndrome refers to the negative effects that downsizing can have on the morale of survivors of downsizing (Kandula 2004). It is a kind of post-traumatic stress disorder (Kupec 2010) that can leave workers emotionally and physically scarred. However, in this research, no direct evidence of survivor’s syndrome was found in the sample, as the emotional and physical health of all workers was found to be at a similar baseline. Survivor’s syndrome theories would be more apt to predict that retrenched workers, who have come closer to the abyss of downsizing, would experience more trauma than their peers, but this finding was not borne out in the study.

It may be the case that Ugandan workers are already steeled by exposure to difficult social and economic circumstances encountered since birth, and are not as psychically fragile as Western workers when it comes to certain kinds of work-related stress; after all, the reality is that many of these workers experience all forms of stress as a daily conditions of their lives in Uganda. Thus, survivor’s syndrome might be more apt to describe the experience of workers in sounder economies and more stable social climates.

Conclusion

It is evident that retrenchment is one of the most undesirable occurrences in an organization but circumstances force it to be there. It is good to note that some eventualities are part of organizational change and need to be incorporated in the management program. This will aid the organization in formulating policies that will have minimum impact on both the organization and the surviving employees. The leadership must put in place mechanisms that will help the survivors cope. The must me incentives to make them motivated, there also must be ways to alleviate the bad feeling as well as apathy that engulfs the organization after a retrenchment exercise. There should be constant surveys and studies to establish the situations on the ground. Once the situations are known, there should be well calculated plans to curtail further spread of whatever side effects that would have been brought by retrenchment. Based on the Equity theory, the Human Resource Management must always be updated on the needs and the expectations of the employees this helps in coming up with comprehensive policies that will be in place to ensure that transition neither hurts the employee or the organization. This can only be achieved by regular surveys on the employee’s attitudes which are bound to change now and then. One evident thing is that the organization has to invest in the employees by conducting regular trainings, workshops and even refresher courses. All this will boost the employees’ confidence towards the organization.

Research Questions

A research question refers to the questions that a researcher to collect the essential data in relation to the issue under investigation (Siedel 1998, p.56). This study will use the following research questions so as to help the researcher meet the objective of the study.

- Is there a relationship between job satisfaction and retrenchment?

- Is there a relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction?

- Does retrenchment have a negative physical impact on survivors in the short-term?

- Does retrenchment have negative emotional impacts on survivors in the short-term?

- Does retrenchment lower job motivation in the short term?

- Does retrenchment lower job satisfaction in the short term?

- How does survivor’s syndrome affect job satisfaction of survivors?

Research Hypotheses

According to Hair et al. (1995) a hypothesis in any research study can be defined as a “formalized statement of a testable relationship between two or more variables” (p. 443). This research study aims to investigate five hypotheses to a certain degree for example the null hypothesis (H0) and the alternative hypothesis (H1).

Continuing with the investigation of the research questions, the hypotheses of this study are:

- H10: There is no relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction.

- H11: There is relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction.

- H20: Retrenchment has no physical impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H21: Retrenchment has physical impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H30: Retrenchment has no emotional impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H31: Retrenchment has emotional impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H40: There is no relationship between retrenchment and motivation in the short term.

- H41: There is relationship between retrenchment and motivation in the short term.

- H50: There is no relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction in the short term.

- H51: There is relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction in the short term

- H60: There is no relationship between Survivors’ syndrome and job satisfaction

- H61: There is relationship between survivors’ syndrome and job satisfaction

Methodology

Introduction

The methodology consists of the following sections: (a) An explanation of the quantitative and qualitative methods chosen for the study (Refer to appendix 2 and 3); (b) a discussion of all the details of study design, including survey design, other constructs and instruments for data collection, hypothesis testing and decision rules, and threats to validity and protects against such threats. Thus, the chapter moves from the general to the specific, and concludes by setting the stage for the data presentation and analysis in chapter four.

Research Questions

In order to carry out an objective research, it was essential to have a properly defined research question. In this study, the following primary research question was therefore used as a guide.

What is the impact of retrenchment on different aspects of job satisfaction of survivors?

In order to analyze specific aspects of this study, the primary research question was further divided into specific research questions as follows:

- What is the relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction?

- What are the physical impacts of retrenchment on public service workers in Uganda?

- What are the emotional impacts of retrenchment on public service workers in Uganda?

- What is the impact of retrenchment on the motivation of public service workers in Uganda?

- What is the impact of retrenchment on the satisfaction of public service workers in Uganda?

Hypotheses

The research used the following hypothesis:

- H10: There is no relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction.

- H11: There is relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction.

- H20: Retrenchment has no physical impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H21: Retrenchment has physical impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H30: Retrenchment has no emotional impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H31: Retrenchment has emotional impacts on survivors in the short-term.

- H40: There is no relationship between retrenchment and motivation in the short term.

- H41: There is relationship between retrenchment and motivation in the short term.

- H50: There is no relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction in the short term.

- H51: There is relationship between retrenchment and job satisfaction in the short term

- H60: There is no relationship between Survivors’ syndrome and job satisfaction

- H61: There is relationship between survivors’ syndrome and job satisfaction

Research Philosophy

This research fell under two groups namely the positivist research or the phenomenological research. According to Easterby -Smith et al (1991, p.27), these two philosophies have been explained in different aspects which were tabled as follow:

Table 3.1: phenomenological approach. Source: Easterby-Smith et al. (1991, p. 27).

Based on the differentiation in the table above, this study used a phenomenological approach based on the following facts:

- The study was carried out in a natural setting and not a laboratory setting.

- The study collected qualitative data through which induction was performed to come up with ideas.

- The researcher was actively implicated in the data collection process.

Available Methodologies for Research

There are two commonly accepted approaches to this research; the qualitative and the quantitative. There are many ways of distinguishing between these two approaches, which can also overlap or complement each other, as in mixed methods designs. However, the basic difference between these methodologies are described by Creswell (1994) as split into five categories as displayed in the following table.

Table 3.2: Differences between Quantitative and Qualitative Research.

The primary methodology employed by this study is quantitative. Within the quantitative method, there are several specific approaches to research. One approach is what Houser (2008) referred to as retrospective studies, which “are conducted using data that have already been collected about events that have already happened” (p. 46). Retrospective studies were common, as researchers worked with collected data to look for patterns and confirm theories. Sometimes such studies are described as primary research, as when researchers collect data from experiments; secondary research is the name given to studies that draw upon data that has been collected by someone else (Jupp, 2006). In the absence of secondary data, it was necessary to generate primary data via either of the two quantitative methods, that is, the experiment or the pseudo-experiment. Brodie, Williams and Owens (1994) argued that the best way to differentiate between these two classes of experiments is through the concept of control. In an experiment, also known as a true experiment, the researcher can “dictate when observations can be made or where and when an independent variable is manipulated within a given group of subjects” (p. 18). Experiments that fail this test are said to be pseudo-experiments.

Since the research questions involved asking subjects about their responses to a past event, the appropriate methodological choice for this project was, by definition, the retrospective study.

Mixed Methods

As this study proposed, mixing qualitative insights from the experimental subjects in addition to quantitative data collected from those subjects, it was necessary to offer a theoretical overview of mixed methods approaches prior to describing how the study design envisions blending the two methods at the level of data analysis.

Flick (2009) is one of the many theorists (see also Green, Camilli, & Elmore, 2006 and Bamberger, 2000) who argued that “quantitative and qualitative methods are not necessarily exclusive, but can be complementary in nature”, and that is how they are in this study. There are several ways in which this complementarily can be achieved. Flick mentioned triangulation of the data set, in which, for example, the findings of a quantitative questionnaire are examined alongside findings from qualitative interviews of the subjects who filled out the questionnaires (Flick, 2009, p. 28).

Naturally, there are several ways in which research designs could establish connections between the two methodologies. Mertens (2009) offers an overview of some of the key possibilities:

qualitative data collected after quantitative data tried to explain the quantitative results or exploratory and sequential designs that are triangulated or embedded parallel designs that are explanatory (p. 298).

Mertens’ (2009) typology of mixed methods built upon Flick’s (2009) discussion. Flick’s argument was that “quantitative and qualitative methods applied to the same research topic invited the research to compare and contrast the two methods’ analytical outputs” (refer to appendix 1 and 2). Mertens’ argument was that the way in which any comparison and contrast proceeded was determined by aspects of the research design. For example, sequential triangulation designs were specifically intended to explore areas of both convergence and disagreement, whereas an explanatory design takes it for granted that there is convergence between the outputs. Thus, study design and approaches to triangulation were closely linked to each other by the academic literature.

To begin with, there is an important distinction between triangulation and embedding. According to Wilbur (2008), the difference is as follows: “The purpose of triangulation is to merge overall different methods of data collection into one overall interpretation, placing an emphasis on both types of data. In the embedded design approach, one dataset provided support role to the other” (p. 117). In order to better to understand the difference between these two approaches, it is necessary to more diligently explore the difference between the concept of an overall, data-merged interpretation and the concept of one form of data providing a support role to the other.

Hesse-Biber and Leavy (2008) offered a description of the embedded method in which he argued that “the embedded data serve to address a secondary purpose within the larger study” (p. 379). What such a secondary purpose might be depends on the precise nature and design of the embedded study; however, Hesse-Biber and Leavy offer the basic example of a qualitative-dominant study in which descriptive statistics are collected on the demographic characteristics of the study subjects. In this case, the demographics of gender and age were actually integrated into the main theme of the study.

Meanwhile, in sequential triangulated approaches, the process of data gathering is designed to serve a single and integrated research function. The variation of sequential triangulated methods employed by this study was what Creswell (1994) refers to as “sequential exploratory, in which there is no prior hypothesis about how the qualitative data will interact with the quantitative data”.

All of these points about mixed methods were revisited in the Study Design section of this chapter, under the heading of data analysis procedures.

In summary, the methodology employed by this study is quantitative, experimental, and primary, although qualitative data was embedded into the findings. All of these approaches are justified by the research questions and are designed to confirm or confound the hypotheses. With the defense of methodological methods concluded, it is time to describe the study design more closely.

Study Design

Study design consists of many components hence this section was broken into the following sub-headings, each of which corresponded to an aspect of study design: (a) Sampling and ethical protections; (b) survey design; (c) data collection procedure; (d) data analysis procedure; and (e) threats to, and protection of, validity.

Research instruments

This study mainly explored a reliable method and instrument of data collection which was the use of a questionnaire. The use of questionnaires has been acknowledged by many researchers to be a reliable method (Foddy 1993, p. 256). This is because the questionnaires are developed under the guidance of the research objectives to ensure that the questions constructed are relevant to the study. In addition, they are user friendly, cheap to construct and administer to the research respondents. Robson (1993, p.178) ascertains that a well developed questionnaire helps the researcher in generating uniform answers from various respondents. The use of open- ended question also helps the respondents to express their views freely because they don’t get restricted in any way. During the construction of the questionnaire, several efforts were made to connect the questions with literature, to devise and organize the questions in a manner that is easy to use and logical to avoid the inclusion of negative questions. Among the things that the researcher also put in consideration are the weaknesses that can be encountered while using questionnaires. Such weaknesses include: absence of the respondents which may force the researcher to use unintended people in answering the questions, and inability to evaluate complex views and opinions.

The developed questionnaire was then taken through various stages aimed at improving its content. The first stage that the questionnaire was exposed to was the pilot test. In this case, the researcher requested five of his peers to act like respondents and respond to the questions. They were required to identify any problems that could help in improving it. Based on the responses, the questionnaire was revised where sequencing was reviewed and some questions rephrased.

Survey Design

The survey was administered in the online survey program known as Survey Monkey. Here are the questions that respondents were asked:

Table 3.3: Summary of the constructs defined in the survey.

Sampling and Ethical Protections

Study population and sample

A population refers to a collection of items of interest in a research study that the researcher uses to generalize the study. Populations are often defined in terms of characteristics, point in time, demography and career. On the other hand, a sample refers to the specific set of items that are directly used in the study. The sample represents the target population and the results that are obtained are used to generalize the whole population (Wood 2010, p.151).

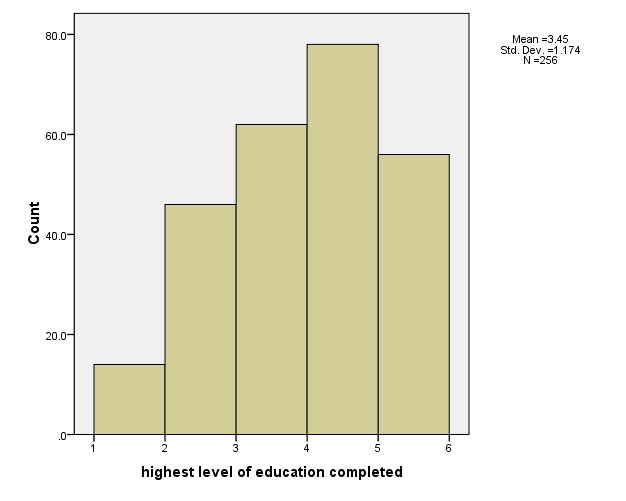

The participants in the research were sampled from the population of retrenched Ugandan civil servants. To ensure that the population was adequately covered and for the ease of statistical calculation a population of 1,000 people was assumed to have been exposed to retrenchment, it was necessary to draw a sample of 256 which is slightly more than 25% of the total population. The basis of testing of the subjects was on a confidence level of 95 percent at a confidence level of 0.05, which are norms in statistical research (Creswell 1994).

Since the study relied on human subjects, it was necessary to adhere to the laid down ethical practices to protect the participants. The research was carried out in accordance with common IRB norms, with attention to the following components: (a) Informed consent and (b) protection of participant and data privacy. Participants who agree to take part in the experiment were asked to sign a consent form to ensure that they participated at their own will. Additionally, the researcher took a number of steps to protect privacy, such as assigning randomly generated numbers, rather than names or identifying information, to mark each set of results (Cortina 1993).

Sampling

In order to obtain precise and reliable data in any given research, it was essential for the researcher to have the correct samples of the respondents. In this research, sampling was done based on the research objectives and because it was only specific information that was sought in this study, the researcher ensured that the instruments used were sent to the specific respondents who had the relevant information that was required (Wood 2010, p.151).

Data Collection Procedure