Introduction

As one of the methods used in the treatment of depression and anxiety, cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) is not only safe but also effective. Psychotherapists have been using CES in the United States and Europe for decades. Although CES has been in clinical use for decades, its safety and efficacy have been for a long time remained questionable because mental disorders vary from one patient to another. In essence, CES requires optimisation to meet certain needs and conditions of patients. Owing to the diversity of mental conditions, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires manufacturers of CES to provide explicit protocols for clinicians to optimise safety and efficacy aspects during treatment (Smith 27; Horowitz 189). Following continued use of CES in the treatment of mental disorders, FDA has approved it after establishing that stringent controls enhance its safety and efficacy (Xenakis par. 1). The approval implies that CES is a significant medical device in psychiatry because it treats a number of psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia.

The efficacy of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety relies on the physiological mechanisms that electric pulses trigger in the brain. A study done on mice reveals that low-intensity electric fields trigger two types of responses, namely, active response and passive response, which voltage-sensitive dye signals show in cortical slices (Xu, Wolff, and Wu 2446). The active response comprises waves that propagate field-induced activity to spread from a locality in cortex to diverse cortical slices. Xu, Wolff, and Wu report that active response is a depolarising signal of voltage-sensitive dye that emanates from positive period of the alternating field (2449). In contrast, passive response is a polarising signal that is present during positive and negative periods of the alternating fields. The active and passive responses exhibit differences in the aspect of amplitude that they elicit. The active response has a linear relationship with the field intensity while the passive response has non-linear relationship with the field intensity. Another difference is that active response has no noticeable threshold in linear relationship with the field intensity whereas passive response has optimum point. Thus, active and passive responses in cortical slices indicates that how CES influences cortical activity and brain physiology.

Experiments done on human subjects indicate that CES influences the levels neurotransmitters in the brain. The biology of the brain shows that depression and anxiety originate from disregulation of neurotransmitters. As a component of the central nervous system, brain has neurotransmitters, which transmit impulses from one neuron to another within the brain. According to Moret and Briley, decreased levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin leads to depression (10). In this view, the function of CES is to stimulate the release of these neurotransmitters and maintain their levels in the brain, and thus, preventing the occurrence of depression. Anxiety occurs when serotonin levels are low and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels are high. In this case, CES increases serotonin levels and decreases suppressive effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid in the brain. Kirsch holds that disregulation of neurotransmitters affects the firing patterns of the brain by determining the dominance or combinations of beta, alpha, delta, or delta waves (17). Hence, CES acts by determining the release of neurotransmitters, and thus, influencing the overall firing pattern of the brain leading to normalisation.

CES is currently an important medical device in psychiatry, which is a product of series of studies. Although the use of CES dates back to centuries ago, records show that it entered into medicine during the mid of the 20 century. Smith states that CES has been in medical use in Europe and the United States since 1953 and 1963 respectively (3). The use of CES in the treatment of mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia has yielded varying outcomes. Hence, psychiatrists experienced difficulties in applying CES and interpreting clinical outcomes among patients. Diverse studies done on humans and experimental animals showed positive outcomes, negative outcomes, and undefined outcomes (Feusner et al. 212; Kirsch 141; Xu, Wolff, and Wu 2450). Meta-analysis of previous studies gives robust outcomes, which support and discredit the use of CES in psychiatry. Therefore, the research paper undertakes meta-analysis to determine the importance of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety.

Since its inception, CES has become an important medical device that psychiatrists rely in the treatment of depression and anxiety. As studies have accumulated numerous outcomes, meta-analysis is essential because it harmonises different outcomes and establishes safety, effectiveness, and optimised protocols of CES. Essentially, meta-analysis is advantageous over a single study because it allows researchers to compare outcomes of diverse patients and numerous protocols under different conditions. Smith states that findings of meta-analysis are more reliable and valid than findings of a single study because it combines findings from diverse studies (5). Thus, meta-analysis of personalised CES on patients suffering from depression and anxiety is essential to establish safety, effectiveness, and optimisation of protocols. Fundamentally, meta-analysis would reveal important findings that support the approval and the use of CES in clinical settings.

Method

The research paper employed meta-analysis as a methodology in selecting and analysing diverse articles that relate to the use of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety in the clinical environment. According to Walker, Hernandez, and Kattan, meta-analysis is a very important methodology because it summarises findings of multiple studies, and thus, it increases validity of findings owing to increased sample size and the power of research (432). The study searched the articles in the electronic databases because they are not only easy to find but also contain reliable articles. Haidich states that electronic databases are appropriate in meta-analysis for they allow systematic searching of articles according to a specific criterion (32). In this case, the study searched for articles in the electronic databases. Russo adds that meta-analysis offers a structured approach that standardises search, aggregation, and analysis of literature in a given field of interest (640). The electronic databases that the study used in searching articles are National Centre for Biotechnology Institute, Science Direct, Elsevier, Taylor Francis Online, and American Institute of Stress.

In selecting articles for meta-analysis, the study employed selection criteria, which considered a number of factors. The first selection criterion is that an article must be a recent publication of not more than 15 years. Recent articles contain updated information, which are valid and reliable, regarding the use of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety. The second criterion is that the article must be a peer-reviewed article published in a journal and assigned volume and issue numbers. Peered-reviewed articles have undergone multiple criticism and assessment by experts, and hence, they contain valid and reliable information for meta-analysis. The third criterion is that the article must be a primary research article. Laboratory studies, clinical studies, and observational studies are types of studies that are important in meta-analysis because they give firsthand information that primary research articles present. The fourth criterion is that the study should use humans as participants. Given that meta-analysis seeks to establish the importance of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety, human subjects and animal models are appropriate participants.

In assessing methodological quality of the research articles selected, meta-analysis considered research questions, objectives, hypotheses, research design, sampling method, data collection, and data analysis. Russo states that methodology is an important in research because it determines validity and reliability of findings (641). In this case, the existence, clarity, and the nature of research questions, objectives, hypotheses, research design, sampling method, data collection, and data analysis determined methodological quality of the research articles used in meta-analysis. To obtain heterogeneity, meta-analysis categorised research articles into different sub-groups according to their research design, types of participants, and interventions used. For meta-analysis to be heterogeneous, it must analyse numerous studies that are similar in an issue of interest, but are diverse in terms of methodology, research design, participants, and interventions employed (Garg, Hackam, and Tonelli 254). Hence, meta-analysis ensured that the selected articles are heterogeneous and reflect the diversity of outcomes in the application of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety.

The primary outcome measures of meta-analysis are safety and efficacy of CES in treatment of depression and anxiety among patients. Since CES is a medical device that has been in use for more than six decades in the United States and Europe, meta-analysis of the primary research articles published in the last 15 years would give valid and reliable information about safety and efficacy in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Safety and efficacy of CES have been the main issues that has delayed it approval by the FDA and adoption by psychiatrists in the clinical environment (Amr et al. 38). The secondary outcomes of meta-analysis are its applications in treatment of other mental disorders in humans and animal models. In this view, comparative analysis of primary outcomes and secondary outcomes are integral in establishing the importance of CES in treatment of depression and anxiety among patients in given clinical settings.

In data collection, the study selected articles from respective databases using predefined criteria. Basing on the aforementioned criteria, the study selected articles that are published in the last 15 years, peer-reviewed, contain primary data, and comprise human subjects and/or animal models. In the collection of data, the study assessed research questions, hypothesis, objectives, methodology, and outcomes. These sections of research articles are pertinent in meta-analysis because they provide data regarding the validity and reliability of findings related to the use of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety. To enhance validity and reliability of data collected, meta-analysis factored missing data and biases in the assessment of articles and data abstraction. The study assessed the magnitude of missing data in various research articles and determined if they have significant effect on the findings. Moreover, the study examined the existence of confounding variables and assessed their biased effects on reporting and publication of findings. The existence of confounding variables contributes to the occurrence of reporting and publication biases in research (Bown and Sutton 673). Owing to the heterogeneity of research articles, participants, methodology, and interventions, the study employed random-effects meta-analysis. Overall, meta-analysis considered missing data and biases in the interpretation of findings in diverse research articles.

Results

This research paper presents results in four sections, namely, the epidemiology and pathophysiology of depression and anxiety, the mechanism of CES, the application of CES in the treatment of depression and anxiety, and the major challenges associated with the use CES in the clinical environment. However, the meta-analysis focused on the application of CES in treatment of depression and anxiety among patients.

Depression and Anxiety

Epidemiology

Epidemiological data indicate that depression is common mental disorder that affects people across the world. Socio-demographic factors such as gender, marital status, age, and economic status contribute to the occurrence of depression in diverse populations. According to the World Health Organisation, depression is a serious mental disorder because it ranks fourth in causing incapacitation and prediction shows that in five years time it will rank second (Kessler and Bromet 120). The existence of socio-economic stressors such as disruption of families, poverty, and physical orders explain the increasing prevalence of depression across the world.

Anxiety is a common mental disorder that people experience in the course of their lives. It normally associates with panic, fear, fright, apprehension, and nervousness leading to serious disorders in the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, nervous, and respiratory systems. The prevalence of anxiety across the world is about 2% and the prevalence among veterans is about 20% (Martin 283). These findings show that anxiety is high among individuals with traumatic experiences, and hence, it relates to depression and stress.

Pathophysiology

Psychiatrists and neuroscientists have formulated hypotheses to explain the pathophysiology of depression. ‘Monoamine hypothesis’ is the first hypothesis, which explains that a reduction in the levels of monoamines prevent dopamine and norepinephrine from transmitting impulses across the synaptic cleft. A reduction in the levels of monoamines in the synaptic clefts causes depression. The hypothesis led to the development of antidepressants, such as MAO inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), during 1960s (Brigitta 8; Kirsch and Gilula 37). The second hypothesis holds that decreased levels of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) leads to depression. This hypothesis led to the development of new anti-depressants such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs). The emergence of neuro-imaging has led to the formulation of the third and fourth hypotheses, which hold that depression occurs due to reduced volume of the brain and high levels of cortisol in basal ganglia, cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus, lead to depression (Brigitta 15). Overall, these hypotheses show that depression occurs when the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain are either high or low, depending on the nature of neurotransmitters.

Just like in depression, dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are neurotransmitters that mediate the occurrence of anxiety. Specifically, low levels of dopamine, serotonin, and epinephrine leads to anxiety, while high levels of GABA lead to anxiety (Moret and Briley 10). In this view, treatment of anxiety requires MAOIs, TCAs, and SRIs. Therefore, comparative analysis of the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety indicates that they share neurotransmitters. Hence, modulation of neurotransmitters by either increasing or inhibiting their concentrations forms the basis of using antidepressants and CES.

The Mechanism of CES

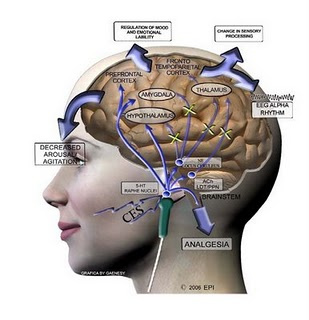

Fundamentally, CES is a medical device that uses electric current in the treatment of mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia. According to Mental Health America, CES stimulates brain and cranium using milliamperes that the body can hardly sense (61). CES is a small device, which is the size of a phone and relies on batteries as the source of power. The device generates electric pulses that stimulate the brain and cranium causing marked physiological changes. Although there is no establish mechanism of CES, researches in both humans and animals theorise a number of mechanisms. The theorised mechanisms of action are parasympathetic stimulation, activation of hypothalamus, stimulation of neurotransmitters’ release, modulation of brain waves, and modify blood flow in the body. Lee at al. argue that CES stimulates neurocytes in the brain leading to enhanced synthesis of dopamine, norepineprhine, and serotonin (1791). A session of CES treatment of about 20 minutes results in a decrease of cortisol leading to a reduced response to stress (Kirsch and Nichols 171; Chen et al. 205). These mechanisms have marked effects on the physiology of the brain leading to the treatment of depression and anxiety. CES has the capacity to generate electric pulses between 0.5 Hz and 100 Hz, which are optimum in the treatment of mental disorders (Schroeder and Barr 2075; Holubec 83). Therapists usually adjust the intensity and the duration of these pulses depending on the condition of a patient and the desired outcomes. Figure 1i below illustrates pathways that CES activates and inhibits during the treatment of depression and anxiety.

The Application of CES in Treatment of Depression and Anxiety

Meta-analysis of 10 studies, which contain 619 as the aggregate number of participants shows the effectiveness, safety, and application of CES in treatment of depression and anxiety under various conditions. Table 1 provides summary of results obtained from the analysis of 10 studies in terms of research design, sample size, intervention, and outcomes. Kennerly undertook a randomised double-blinded controlled study among 30 normal volunteers and found out that CES treatment using 0.5 Hz led to a significant decrease in frequencies of beta and delta waves (112). This study shows that CES effectively reduces frequencies of theta and delta in the brain resulting in the treatment of depression and anxiety. A similar study done on 12 normal males indicates that CES treatment using 0.5-100 Hz decreases frequencies of beta and alpha waves significantly in the brain, p = 0.001 (Schroeder and Barr 2075). The study shows that even high-frequency CES effectively lowers beta and alpha waves in the brain resulting in reduced levels of anxiety and depression among normal individuals.

Four studies illustrate the safety and effectiveness of CES in treatment of anxiety and depression among patients in diverse conditions. A study done on 115 patients with anxiety disorders shows that anxiety and depression levels in CES group were significantly lower than in sham group at 95% confidence interval (Barclay and Barclay 171). The findings effectively support the use of CES in the treatment of patients with anxiety disorders. Another study done to establish the effect of 200 µA CES on patients with preoperative anxiety aged between 18 and 65 indicates that CES group had a considerably lower anxiety when compared to control group (Kim et al. 657). In this view, it is evident that high-ampere CES can effectively reduce anxiety among patients with preoperative anxiety. CES is effective in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder because a study done among 73 patients depicted significant improvement in the mood (Zhang et al. 12). Moreover, Loo et al. applied direct current stimulation on patients with depression and found out that it improves mood and stabilises neuropsychological functioning (52). These four studies, therefore, show that CES is not only effective in treatment of anxiety and depression, but it is also safe.

CES is also applicable in treatment of anxiety and depression among children. Yixin et al. performed a randomised controlled study among 60 children aged between 8 and 16 found out that mean scores of depression and anxiety in CES group were significantly lower than in sham group after applying 100-500 µA. This study shows that high-ampere CES is safe and effective in treatment of depression among children. A study done to evaluate safety and effectiveness of a session of CES in the treatment of 32 children with mixed anxiety and depression disorder (MAD) shows a significant decline in the anxiety and depression scores. Hence, these findings reveal that CES is an effective and safe method of treating children with anxiety and depression. Other studies performed among special groups such as Sherriff’s staff, service members, and veterans indicate that CES is effective and safe method of treating anxiety and depression (Taylor et al. 36; Gilula and Barach 271). Mellen and Mackey undertook a randomised controlled study and established that 100 µA CES results in a decreased depression levels among 21 Sherriff’s staff (9). A survey done among 152 service members and veterans indicated that 65.3% perceived CES to be effective and 99% perceived it as safe (Marksberry et al. 311). The findings are reliable and valid because of the significant power of the questionnaire and 95% confidence interval. Overall, the findings of the survey show that service members and veterans regard CES as appropriate method of treating depression and anxiety.

Table 1

Sensitivity analysis indicates that the findings of these studies are valid and reliable because of the research design, participants, sample sizes, and interventions. The design of all studies entails randomisation, and thus, their findings are not prone to researchers’ biases. Moreover, researchers blinded these studies using either single-blind or double-blind to prevent researchers and participants from introducing their biases into the study. Blinding is important in research because it prevents differential treatment or assessment of participants due to prevailing biases (Karanicolas, Farrokhyar, and Bhandari 346). Hence, blinding in these studies is very significant because it enhances internal and external validity of findings. Although sample sizes vary from one study to another, pooled samples is 619, which is sufficient to improve external validity of findings, and hence, their generalisability. Finfgeld-Connett states that large sample sizes enhance representativeness of the population and improve generalisability of findings (348). Furthermore, the samples represent the population because they comprise children, adults, normal individuals, patients, veterans, and service members. The diversity of interventions enhances reliability and validity of findings. Given that the analysed studies used different CES in terms of frequencies and amperage, their collective findings indicate that CES is safe and effective in treatment of depression and anxiety in different conditions.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although CES has been in use in clinical settings for decades, its safety and efficacy is not fully established. Epidemiological data indicate that anxiety and depression are serious mental disorders, which have debilitating effects on people. Pathophysiology indicates that anxiety and depression occur due to imbalances of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Hence, CES works by restoring the imbalances of these neurotransmitters (Kennerly 22; Krause, Marquez-Ruiz, and Kadosh 605). Meta-analysis indicates that CES is applicable in the treatment of anxiety and depression among normal individuals and patients. Moreover, meta-analysis shows that CES is safe and effective in treatment of anxiety and depression among children, adults, and the elderly. Evidently, meta-analysis support most studies that CES is safe and effective method of treating anxiety and depression among individuals across all age groups (Davey et al. 358; Marksberry et al. 312; Schroeder and Barr 2075; Zhang et al. 12). Essentially, CES is a versatile method of treating anxiety and depression because clinicians can adjust frequency or amperage depending on the conditions of a patient.

In conclusion, the meta-analysis provides ample evidence, which indicates that CES is not only effective but also safe in the treatment of anxiety and depression. Sensitivity analysis indicates that the findings of the articles assessed are valid and reliable because they emanate from randomised, blinded, and controlled studies. The blinding reduces biases that originate from participants and researchers, and hence, meta-analysis is not prone to significant effects of biases. Moreover, pooled sample of 619 participants enhance generalisability of the findings.

References

Amr, Mostafa, Mahmoud El-Wasify, Ahmed Elmaadawi, Jeannie Roberts, and Rif El-Mallakn. “Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation for the Treatment of Chronically Symptomatic Bipolar Patients.” Journal of ECT 29.2 (2013): 31-39. Print.

Barclay, Timothy, and Raymond Barclay. “A clinical trial of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for anxiety and comorbid depression.” Journal of Affective Disorders 164.1 (2014): 171-177. Elsevier. Web.

Bown, Matt, and Alex Sutton. “Quality control in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.” European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 40.1 (2010): 669-677. Elsevier. Web.

Brigitta, Bondy. “Pathophysiology of depression and mechanisms of treatment.” Dialogues of Clinical Neuroscience 4.1 (2002): 7-20. NCBI. Web.

Chen Yixin, Yu Lin, Zhang Jiuping, Li Lejia, Chen Tunong, and Chen Yi. “Results of cranial electrotherapy stimulation to children with mixed anxiety and depressive disorder.” Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry 19.4 (2007): 203-205. Print.

Davey, Mark, Leonard Barratt, Paul Butow, and John Deeks. “A one-item question with a Likert or Visual Analog Scale adequately measured current anxiety.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60.4 (2007): 356-360. Print.

Edmonton Neurotherapy: Brain Stimulation Therapies 2015. Web.

Feusner, Jamie, Sarah Madsen, Teena Moody, Cara Bohon, Emily Hembacher, Susan Bookheimer, and Alexander Bystritsky. “Effects of cranial electrotherapy stimulation on resting state brain activity.” Brain and Behaviour 2.3 (2012): 211-220. Print.

Finfgeld-Connett, Deborah. “Generalisability and transferability of meta-synthesis research findings.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 66.2 (2010): 246-254. Print.

Garg, Amit, Dan Hackam, and Marcello Tonelli. “Systematic review and meta-analysis: When one study is just not enough.” Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 3.1 (2008): 253-260. Print.

Gilula, Marshall, and Daniel Kirsch. “Cranial electrotherapy stimulation review: A safer alternative to psychopharmaceuticals in the treatment of depression.” Journal of Neurotherapy 9.2 (2005): 7-25. Science Direct. Web.

Gilula, Marshall, and Paul Barach. “cranial electrotherapy stimulation: a safe neuromedical treatment for anxiety, depression or insomnia.” Southern Medical Journal 97.12 (2004): 269-270. Print.

Haidich, Anna-Bettina. “Meta-analysis in medical research.” Quarterly Medical Journal 14.1 (2010): 29-37. Print.

Holubec, Jerry. “Cumulative response from cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) for chronic pain.” Practical Pain Management 9.9 (2009): 80-83. Print.

Horowitz, Sala. “Transcranial magnetic stimulation and cranial electrotherapy stimulation.” Alternative and Complementary Therapies 19.4 (2013): 188-193. Print.

Karanicolas, Paul, Forough Farrokhyar, and Mohit Bhandari. “Blinding: Who, what, when, why, how?” Canadian Journal of Surgery 53.5 (2010): 345-348. Print.

Kennerly, Richard. “QEEG analysis of cranial electrotherapy: A pilot study.” Journal of Neurotherapy 8.2 (2004): 112-113. The American Institute of Stress. Web.

Kessler, Ronald, and Everlyn Bromet. “The epidemiology of depression across cultures.” Annual Review of Public Health 34.1 (2013): 119-138. NCBI. Web.

Kim, Jung, Young Kim, Sook Lee, Seok Chang, Hwan Kim, and Cheol Park. “The effect of cranial electrotherapy stimulation on preoperative anxiety and hemodynamic responses.” Korean Journal of Anaesthesiology 55.6 (2008): 657- 661. The American Institute of Stress. Web.

Kirsch, Daniel. The science behind cranial electrotherapy stimulation. Edmonton: Medical Scope Publishing Corporation, 2002. Print.

Kirsch, Daniel, and Francine Nichols. “Cranial electrotherapy stimulation for treatment of anxiety, depression, and insomnia.” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 36.1 (2010): 169-176. Elsevier. Web.

Kirsch, Daniel, and Marshall Gilula. “Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation in the Treatment of Depression.” Practical Pain Management 7.5 (2007): 32-40. Print.

Krause, Beatrix, Javier Marquez-Ruiz, and Roi Kadosh. “The effect of transcranial direct current stimulation: A role for cortical excitation/inhibition balance.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7.2 (2013): 602-610. Print.

Lee, Se-Hwa, Woon-Young Kim, Chang-Hyung Lee, Too-Jae Min, Yoon-Sook Lee, and Young-Cheol Park. “Effects of cranial electrotherapy stimulation on preoperative anxiety, pain and endocrine response.” Journal of International Medical Research 14.6 (2013): 1788-1795. SAGE. Web.

Loo, Colleen, Angelo Alonzo, Donel Martin, Philip Mitchell, Veronica Galvez, and Perminder Sachdev. “Transcranial direct current stimulation for depression: 3-week, randomised, sham-controlled trial.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 200.1 (2012): 52-59. Elsevier. Web.

Lu, Yen-Hsun, Hao Wang, Sah Zhang, Xiang Liu. “Safety and effectiveness of cranial electrotherapy stimulation in treating children with emotional disorders.” Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation 9.8 (2005): 96-97. The American Institute of Stress. Web.

Marksberry, Jeff, Daniel Kirsch, Francine Nichols, Larry Price, and Katherine Platoni. “Efficacy of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation for Anxiety, PTSD, Insomnia and Depression: Military Service Members and Veterans Self Reports.” Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation 8.3 (2015): 311-312. NCBI. Web.

Martin, Patrick. “The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: A review.” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 5.3. (2003): 281-298. NCBI. Web.

Mellen, Ronald, and Wade Mackey. “Reducing sheriff’s officers’ symptoms of depression using cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES): A control experimental study. The Correctional Psychologist 41.1 (2009): 9-15. The American Institute of Stress. Web.

Mental Health America 2012, Complementary and Alternative Medicine: A comparative evidence-based approach to complementary and alternative treatment for mental health conditions. PDF File. Web.

Moret, Chantal, and Mike Briley. “The importance of norepinephrine in depression.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 7.1 (2011): 9-13. Print.

Russo, Mark. “How to review a meta-analysis.” Gastroenterology & Hepatology 3.8 (2007): 637-642. Print.

Schroeder, Megan, and Ronald Barr. “Quantitative analysis of the electroencephalogram during cranial electrotherapy stimulation.” Clinical Neurophysiology 112.11 (2001): 2075-2083. Elsevier. Web.

Smith, Ray. Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation: Its First Fifty Years, Plus Three: A Monograph. Washington: Tate Publishing, 2006. Print.

Taylor, Ann, Joel Anderson, Shannon Riedel, Janet Lewis, and Cheryl Bourguignon. “A randomised, controlled, double-blind pilot study of the effects of cranial electrical stimulation on activity in brain pain processing regions in individuals with fibromyalgia.” Explore 9.1 (2013): 32-40. Print.

Walker, Esteban, Adrian Hernandez, and Michael Kattan. “Meta-analysis: Its strengths and limitations.” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 75.6 (2008): 431-439. Print.

Xenakis, Stephen. The rise of cranial electrotherapy. 2014. Web.

Xu, Weifeng, Brian Wolff, and Jian-young Wu. “Low-intensity electric fields induce two distinct response components in neocortical neuronal populations.” Journal of Neurophysiology 112.1 (2014): 2446-2456. Print.

Yixin, Chen, Zhang Juping, Li Lejia, Chen Tunong, and Chen Yi. “Results of cranial electrotherapy stimulation to children with mixed anxiety and depressive disorder.” Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry 19.4 (2007): 203-205. The American Institute of Stress. Web.

Zhang, Zhang-Jin, Roger Ng, Tsui Li, Wendy Wong, Qing-Rong Tan, Hei Wong, and Vivian Wong. “Dense Cranial Electroacupuncture Stimulation for Major Depressive Disorder: A Single-Blind, Randomised, Controlled Study.” PLoS ONE 7.2 (2012): 1-22. NCBI. Web.